1 Bumbershoot ’76

Public Art and Community Leisure

Maya Green

Abstract

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) is widely known and rightfully appreciated for his early paintings depicting epic stories from American history, but the work from the last half of his career is woefully understudied. Having moved away from the global artistic center of New York City in 1971, Lawrence spent the rest of his life painting and teaching in Seattle, Washington. After this cross-continental relocation, how did Lawrence become involved in local art production and what impact did this have on his creative work? In this essay, I argue that starting with Bumbershoot ‘76 (1976), a painting-turned-print commissioned for a city-sponsored art and music festival, Lawrence became deeply engaged in Seattle’s public art scene. Bumbershoot ‘76 conforms to Lawrence’s canon through its social content and figurative style; its dissemination as a print also fits neatly as the 1970s were a period when many of his older paintings and new creations were being translated into prints. But Bumbershoot ‘76 stands out as a celebration of leisure in community and collective engagement with open public spaces, rather than of labor — a theme that was explored in his many Builders paintings created around the same time.

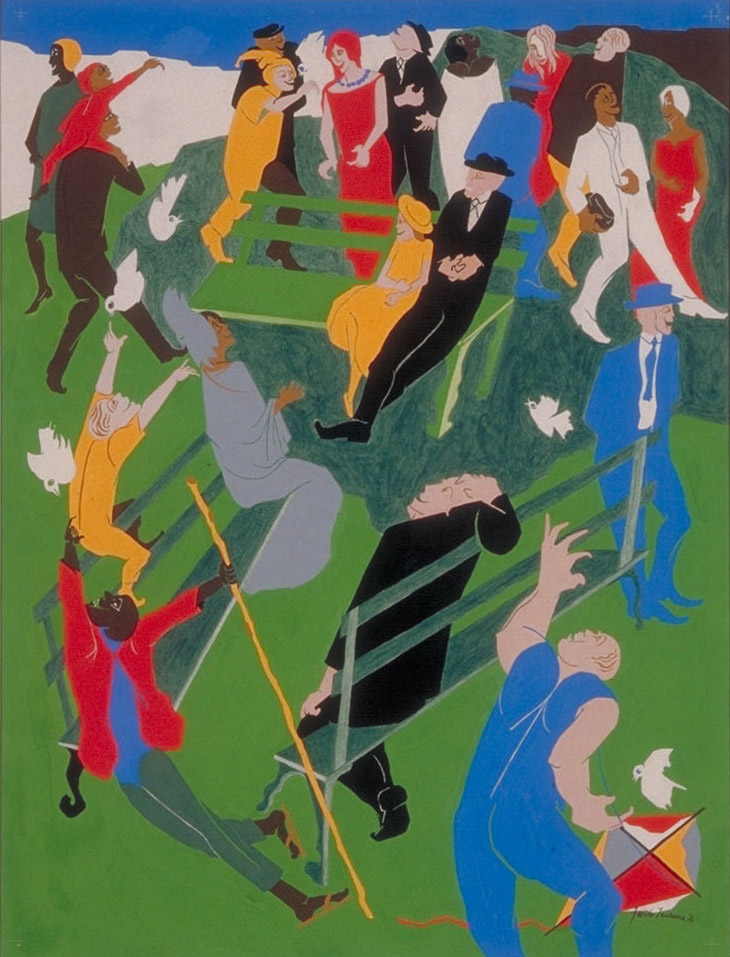

Five years after relocating to Seattle, Jacob Lawrence was commissioned to create the promotional poster for Bumbershoot, a city-sponsored art and music festival held annually at the Seattle Center. First painted with gouache on paper and then translated into silkscreen prints, Bumbershoot ‘76 (1976) represents Lawrence’s early integration into the public art scene in Seattle (fig. 1, fig. 3). There are a few other examples of this mode of working: in the 1970s and 1980s, Lawrence created at least four paintings intended to be used as posters and oversaw the process of translating many of his earlier works from paint to print. However, created amid his notable Builders paintings, and following commissions for the Washington state capitol building, Bumbershoot ‘76 stands out both formally and thematically from the rest of his oeuvre.[1] Rather than glorifying scenes of human labor or highlighting forgotten local history, as those previous commissions had done, Bumbershoot ‘76 features an idealized community and celebrates the pure leisure that the festival sought to create.[2] Not only was the poster commission the start of a long relationship with the City of Seattle’s municipal arts institutions, but the design was also one of his first creations specifically for the Northwest. Despite these defining characteristics that make Bumbershoot ‘76 something of an anomaly among Lawrence’s work, the painting has received only passing mention by scholars of the artist. This study is the first to place the poster in the context of Lawrence’s engagement with public art in Seattle.

Analyzing Bumbershoot ‘76 in light of the festival’s initial social goals supports an interpretation of the work as a celebration of civic life and the role of art in facilitating community development. Following the post-war boom in Seattle’s industrial economy, the 1970s brought what is locally known as the “Boeing Bust.”[3] Amid rising inflation and unemployment nationwide, the Mayor of Seattle, Wes Uhlman, proposed a city arts festival to “keep the human spirit going.”[4] Around the same time, the recently-founded Seattle Arts Commission was considering organizing a festival, and the city went forward with sponsoring a summer event.[5] The sheer diversity of acts and entertainers led local commentators to label it a “populist grab-bag” of a lineup.[6] Bumbershoot was the definition of a “big tent” festival, sure to have something for everyone. The event’s location at the Seattle Center furthered the Commission’s goal of enhancing city life through the arts. As the former site of the 1962 Seattle World Fair, and featuring a diverse range of performance and gathering venues, the Seattle Center was well suited to accommodate the hundreds of thousands of festival-goers. [fig. 2] [7] At the time Lawrence would have been designing his poster, the Seattle Center also housed a pavilion of the Seattle Art Museum, making it the real geographic center for visual and performing arts in the city.[8] Following the Bumbershoot poster, Lawrence participated in many projects organized by the Seattle Arts Commission, and a dozen of his paintings were purchased for the City of Seattle’s public art collection. Archived correspondence with local officials shows that the City was eager to incorporate him into public projects and that Lawrence was often happy to oblige.

Visualizing Community

While the City already established its official position that public art enhances mutual understanding within communities and therefore the government has an obligation to financially support creative work, Jacob Lawrence’s Bumbershoot ‘76 provides a visual example of those ideals.[9] Set against the Harlem tenements or crowded city streets of Lawrence’s most well-known paintings, Bumbershoot ‘76 is comparatively open and green. Lawrence likely took inspiration from the Seattle Center’s expansive lawns and grassy slopes ringed by community cultural centers, which were transformed into amphitheaters and outdoor stages during the festival. Despite filling the poster with twenty-one figures, Lawrence avoids a feeling of claustrophobia by employing undisturbed patches of green grass and a glimpse of the open sky. Two shades of green are used in the poster; the bottom half of the painting is a light green broken up by two darker green benches, and the top half is an inverse dark green patch with a single lighter-toned bench. The lighter shade of grass is formed in a large “U” shape, accentuated by the placement of the benches and positioning of the figures in the foreground. This composition creates a dynamic swooping effect, drawing the viewer’s eye cyclically around the scene. White birds flutter around the crowd and five of the figures stretch out their hands as if to feed them. Collectively, the birds and the U-shaped composition are a connection between otherwise disparate couples and families enjoying the public greenspace.

Lawrence creates a sense of community through tolerant cohabitation to elevate the message of Bumbershoot as a free event for revitalizing the human spirit. He achieves this in part through his styling of the crowd, details that show pride of place. Men wear suits, ties, and hats, and women don dresses and visible jewelry. Something special must be happening here, because in Seattle in the 1970s (and today) these outfits would be far from casual daywear. The open public park provides neighbors a place to see each other at their best. This fashioning indicates that the work is not strictly illustrative of a scene Lawrence observed in his new city, but shows an idealized version of a community coming together to enjoy their shared environment.

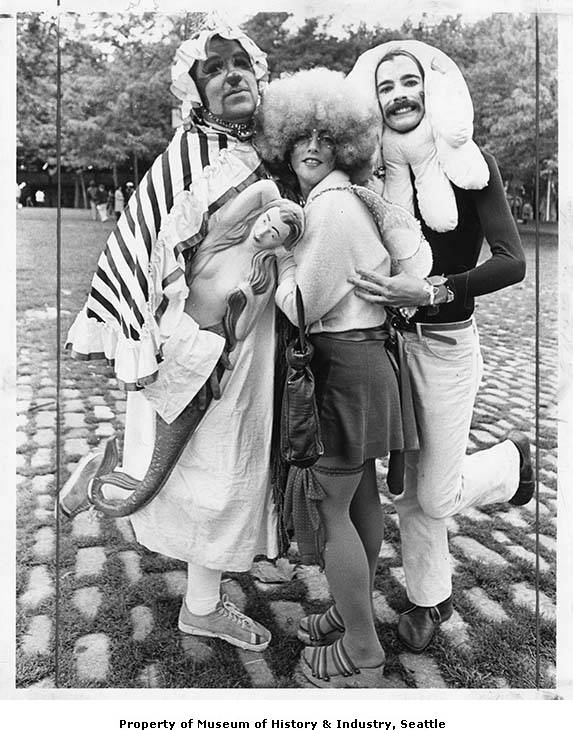

However, not everyone is dressed to the nines. A figure in a burnt-yellow smock near the top of the frame wears a cap that takes an ambiguous form partway between a court jester and a wizard’s hat. The pant legs on this figure are two colors, one yellow and one brown, contrasting with the rest of the crowd’s mainly monochrome attire. This jester is mirrored by another small figure in yellow, also with two-toned pants. These two individuals could be a reference to the eccentric costumes that many festival-goers wore (fig. 4) or to the popular vaudeville performances that took place in the early years of Bumbershoot.[10] Despite their slightly comical nature, neither of these jesters takes away from the overall unity of the community shown, implying a certain level of tolerance; although they wear less formal attire, they engage the birds and enjoy the park along with the rest of the crowd. The choice to depict the crowd in this way, combining the elegant with the comical, alludes to the wide variety of acts at Bumbershoot that supported the event’s identity as a festival for the people in all their differences.

Another way Lawrence shows an ideal of community in Bumbershoot ‘76 is through the racial makeup of the crowd. Half the figures are Black or people of color and half are painted White.[11] However, at the time of creation, this would not have been reflective of Seattle’s demographics. At the 1970 census, the city of Seattle was an overwhelming ninety-three percent White. Ellen Harkins Wheat, commenting on Lawrence’s Pacific Northwest Arts and Crafts Fair (1981) poster (fig. 5), argued that the commission featuring a mostly-White crowd allowed the artist to “indulge in wry social observation.”[12] This is a contrast to the Builders in which, according to Wheat, it was “highly significant that in these works different ethnic groups are depicted working together toward mutual goals.”[13] The crowd at Bumbershoot would not be much different than the crowd at the Arts and Crafts Fair, but for Bumbershoot ‘76 Lawrence depicted demographic parity. While the Builders’ multi-ethnic construction crews emphasize that labor and collective creation can be a means for unity, these people in the park do not fit into this conception of achieving equity through shared work. Instead, in Bumbershoot ‘76, Lawrence offers an illustration of the fact that work is not the only way to unity and that mutual advancement also requires collective, integrated leisure, not just labor.

Despite the unique theme, this mode of creation – a commissioned painting to be printed as a promotional poster – was a growing genre of work for Lawrence. More broadly, this took place in the context of Lawrence’s increased interest in printmaking from the early 1970s through the end of his career. Peter T. Nesbett, author of Jacob Lawrence: the Complete Prints, 1963-2000 and co-director of the Jacob Lawrence catalogue raisonné project, places the artist’s period of printmaking within the broader “growing market for limited edition prints” from the 1960s onward. Prints not only allowed popular artists to offer lower-cost versions of their work, but artists also recognized its “aesthetic potential…and its ability to reach new audiences” — two factors that are present in the creation and dissemination of Bumbershoot ‘76.[14] The Seattle Arts Commission, the festival’s primary sponsor, made 500 editions of the Bumbershoot poster to distribute freely around the city, making the design much more likely to be widely appreciated than if only the original painting was placed on view in a gallery, museum, or even a non-arts specific public building.[15]

Nesbett notes that Bumbershoot ‘76 was created in an era of “increased graphic activity” for Lawrence.[16] Building on his substantial production of prints, Wheat highlights the “influence of graphics” in Lawrence’s paintings as a result. Wheat argues that this influence appears in his Builders paintings, finding that his “shapes are flatter, often solid and unmodulated, and details of facial features are almost eliminated.”[17] These observations hold when examining Bumbershoot ‘76, and in particular when comparing the original painting to the printed poster version. Except for losing some texture on the darker patch of grass and dark green benches, the two versions are nearly identical. The color palette is just as limited in the painting as in the print: one tone each of red, yellow, blue, and gray; two tones of green; three skin tones; black and white. The clothing and figures are painted with no shading, almost as if they are paper cut-outs, placed on a green background. Even among Lawrence’s many prints from the surrounding decades, Bumbershoot ‘76 shows a particularly keen sensibility for creating a bold, eye-catching graphic design that would read clearly across varying media.

While prints were becoming more common projects for Lawrence, open green space was still rare for the artist and just two other examples of his paintings-turned-posters employ a similarly grassy composition. The Munich Olympic Games (1971-72) poster which, as the title suggests, was prepared for the international sporting event, features five Black track runners, three simultaneously crossing the finish line with batons in hand (fig. 6). They are framed by patches of grass through which the track cuts in a tight arc. Pacific Northwest Arts and Crafts Fair (1981) is much more locally oriented. Taking place just outside of Seattle in Bellevue, Washington, this work would have been seen by regional artisans and arts supporters attending the event. The Arts and Crafts Fair uses a two-tone scheme for the grass similar to Bumbershoot ‘76, but rather than showing leisurely park-goers it depicts creators at work. Completed at the height of his Builders theme, Lawrence echoes those forms through tools and work tables but placed them among a crowd of visitors. Despite some formal similarities, the subjects shown in Munich and Arts and Crafts Fair have a different feel than Bumbershoot ‘76. Munich is a scene of competition, with the definition of the athletes’ leg muscles emphasizing the intense physical labor they put in to reach the finish line of such a prestigious competition. Arts and Crafts Fair similarly highlights physical as well as creative labor, and emphasizes an economic exchange; visitors approach artisans to examine their wares for possible purchase. But Bumbershoot ‘76 is significant in that it shows a scene of community leisure, of co-existing in public space, without the ulterior motives of profit or glory.

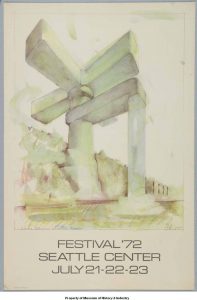

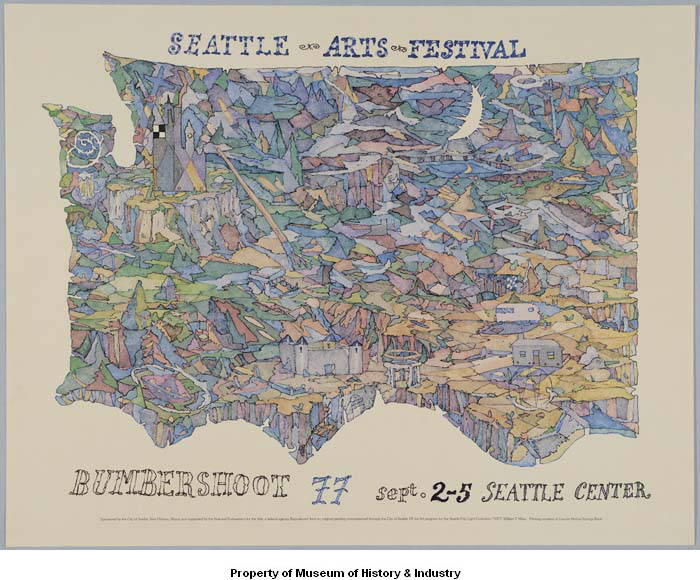

None of the other Bumbershoot posters from the decade surrounding Lawrence’s commission feature the ideals of public art and community so directly as his contribution. He stands out for not engaging with some of the most obvious visual signifiers of the festival, most notably the rainbows and umbrellas visible in the posters from 1973, 1974, and 1975, which are absent from his design. Instead, Lawrence places the social nature of public art front and center in Bumbershoot ‘76. Other posters feature natural imagery typical of the Northwest — greenery, mountains, water (often in the form of rain) — but strip them of their relationship to the people who experience them. Even the 1972 poster designed by Claes Oldenberg, one of the most widely-known artists of the twentieth century, engages with nature in an abstracted sense by depicting an oversize faucet pouring water into Lake Union (fig. 7). Lawrence highlights the natural beauty of the region, but does so in the context of community and puts more “emphasis (sic) on the carnival atmosphere of the urban celebration.”[18] Rather than symbolically referencing something visually recognizable as Seattle, Lawrence reconstructs the feeling of collective enjoyment in public space that is created each year through the Bumbershoot festival. This is especially notable considering that Lawrence himself sat on the selection committee for the 1977 poster — a design in which human presence in the state of Washington is only indicated through references to the built environment (fig. 8). Despite being a relative newcomer to Seattle, and with the festival still in its early years, Lawrence visually celebrates local community, civic space, and public engagement with the arts.

Public Space, Public Art

Jacob Lawrence’s celebration of public space and public support for the arts is expressed not only through the subject matter depicted in Bumbershoot ‘76, but also in statements made throughout his career. In a 1969 roundtable discussion on the place of Black artists in the U.S. art world, only two years before moving to Seattle, he asserted:

“The greatest exposure for the greatest number of people came during this period [the 1930s] of government involvement in the arts… The government has made stabs at it – you’ve got various committees and they’ve given stipends, but nothing massive like the thing thirty years ago. I think what we need is a massive government involvement in the arts – by municipal groups or by the state…” [19]

Even Seattle’s relatively ambitious and progressive support for local arts and culture may not have sufficed for Lawrence in this perspective. Regardless of any shortcomings, he made clear his support for these programs through his direct participation.

From 1976 onward Lawrence was engaged with various projects of the Seattle Arts Commission, a city department that sponsored and organized the Bumbershoot festival in its first decade. Among U.S. cities, Seattle was at the forefront of public arts support and funding in the 1970s. The Arts Commission was established in 1971 and in 1973 the City passed the “1% For Art” funding mechanism. Seattle has “one of the first” municipal programs in the country that devotes a percentage of funding for capital projects to the “commission, purchase, and installation of artworks throughout the city.”[20] The City was eager to play a role in developing the local arts scene through this funding, with the Ordinance instituting the fund stating

“The City of Seattle accepts a responsibility for expanding experiences with visual art. Such art has enabled people … to better understand their communities and individual lives. Artists capable of creating art for public places must be encouraged and Seattle’s standing as a regional leader in public art enhanced.” [21]

The text of the ordinance takes an instrumental stand on the role of art: it can and should play an active role in community development.

Even though the festival later transitioned to a more corporate model, partnering with major concert promoters and charging attendees hundreds of dollars for weekend tickets, from 1971 to 1980, Bumbershoot offered free admission and ran on a shoestring budget supplied by the City and outside grantmakers. The festival was by and for locals, with “nearly 100 percent” of the budget “spent on local talent,” including musicians, comedians, and performers.[22] While it is unclear how much Lawrence knew about the festival itself, from his letter exchanges with John Blaine of the Seattle Arts Commission, he was surely aware that it was a free, city-sponsored event — showing Lawrence’s support for, and recognizing the value of public investment in, local arts.[23]

After completing the Bumbershoot poster, Lawrence continued his engagement with the Seattle Arts Commission and other culturally-focused City departments. In May 1977, Lawrence received a letter from Pat Fuller, coordinator of the Art in Public Places program, confirming the details of an upcoming meeting for the selection of that year’s Bumbershoot poster. From the letter, it appears Lawrence agreed to serve on the jury to select the artist who would create the next poster after having completed the 1976 commission himself. Fuller writes: “Enclosed is your contract and invoice, which allows for the Arts Commission to pay you a regrettably nominal fee for your participation.”[24] Already employed by the University of Washington as a full professor, having had many major exhibitions, and considered one of the foremost American artists at the time, Lawrence would not have needed to participate in this process for financial gain.[25] Instead, this continued engagement with the City, and Bumbershoot in particular, shows he felt some alignment with the values and goals of these municipal art institutions.

Correspondence between Lawrence and various administrators of the Arts Commission continued for a decade following Bumbershoot ‘76, further showing a commitment to supporting local public art. In May 1980, Barbara Thomas of the Artists-in-the-City Program requested Lawrence’s support for an Emancipation Celebration exhibition, stating that his “participation would ensure our City and its visitors are given the opportunity to share in the riches of our present-day ethnic cultural heritage” and that he was among “a select group of Black artists” invited to contribute artwork.[26] Barbara Thomas, more widely known as Barbara Earl Thomas, is a former student of Lawrence’s and was a close friend of him and his wife, artist Gwendolyn Knight. Not only was his work continually requested for public showing in City programs, but Lawrence’s mentees also became deeply involved in local arts institutions.[27] In addition to regularly requesting his expertise and temporary loans for exhibitions, letters from between 1980 and 1982 show the City was actively collecting Lawrence’s work for permanent municipal collections. Seattle City Light repeatedly asked to purchase paintings from Lawrence and, unsatisfied with only acquiring the “two small works” bought through Francine Seders Gallery, commissioned an original painting for City Light’s Portable Works Collection.[28] These purchases, like the Bumbershoot poster commission, were financed through the 1% For Art fund.

Today, the City of Seattle’s Portable Works Collection holds sixteen original works by Lawrence, a combination of paintings and prints, of which fourteen were purchased by City Light.[29] Although in the original agreement for the Bumbershoot ‘76 commission Lawrence was set to retain the original painting, the City now owns that as well.[30] With each letter, request, purchase, and commission, Lawrence became more integrated into Seattle’s municipally-supported arts scene.

Poster Puzzles

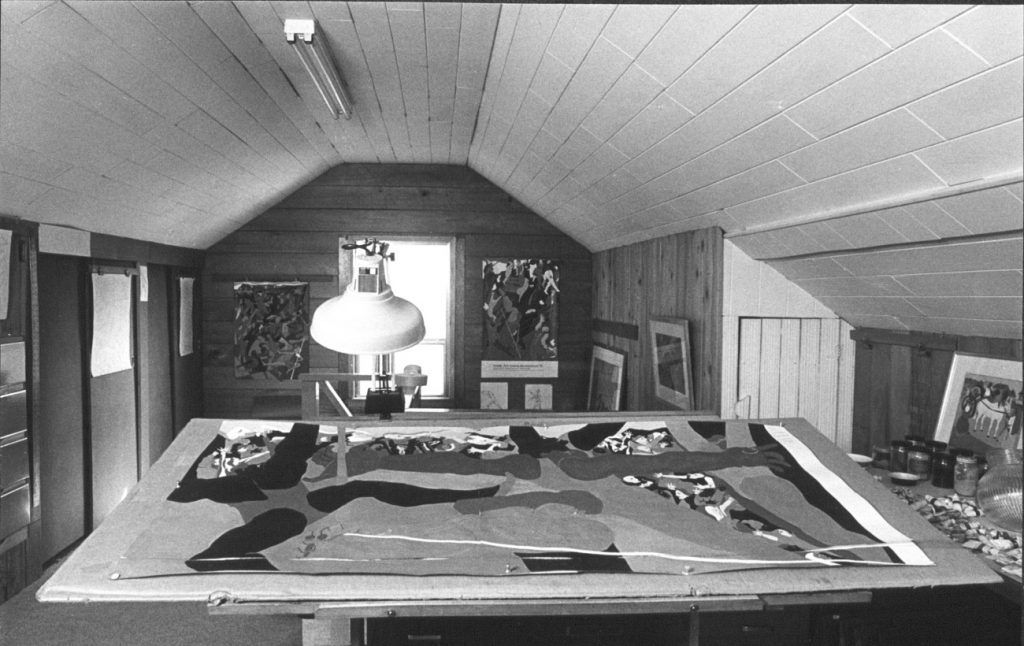

While it is clear that Lawrence’s participation in the Bumbershoot commission and his subsequent collaboration with municipal art projects were of great value to the City, the importance of Bumbershoot ‘76 to Lawrence himself presents a puzzle. Photographs of Lawrence’s home studio in Seattle show that a poster version of Bumbershoot ‘76 was tacked to the wall at the top of the stairs that led to his workspace. This position means every time Lawrence went up to work, he would be directly confronted with the design. A 1979 photograph (fig. 9) shows Bumbershoot ‘76 positioned to the right of a window, and Builders (Red and Green Ball) (fig. 10) hanging to the left. These two paintings share a key similarity. Both feature a man in a lower corner of the frame, with a long stick in hand, leaning so their feet seemingly bear none of their body weight. The arrangement within the studio makes the poles point towards each other, coming to an implied point above the window frame. Paired with the painting on the worktable, which is likely Games (1978) that Lawrence completed as a study for his mural at Seattle’s Kingdome Stadium, means that the photograph was probably taken in 1979. This timeline shows that Lawrence put up the Bumbershoot ‘76 poster shortly after he received a copy; not hanging it out of later nostalgia, but giving it an important visual placement soon after its creation.

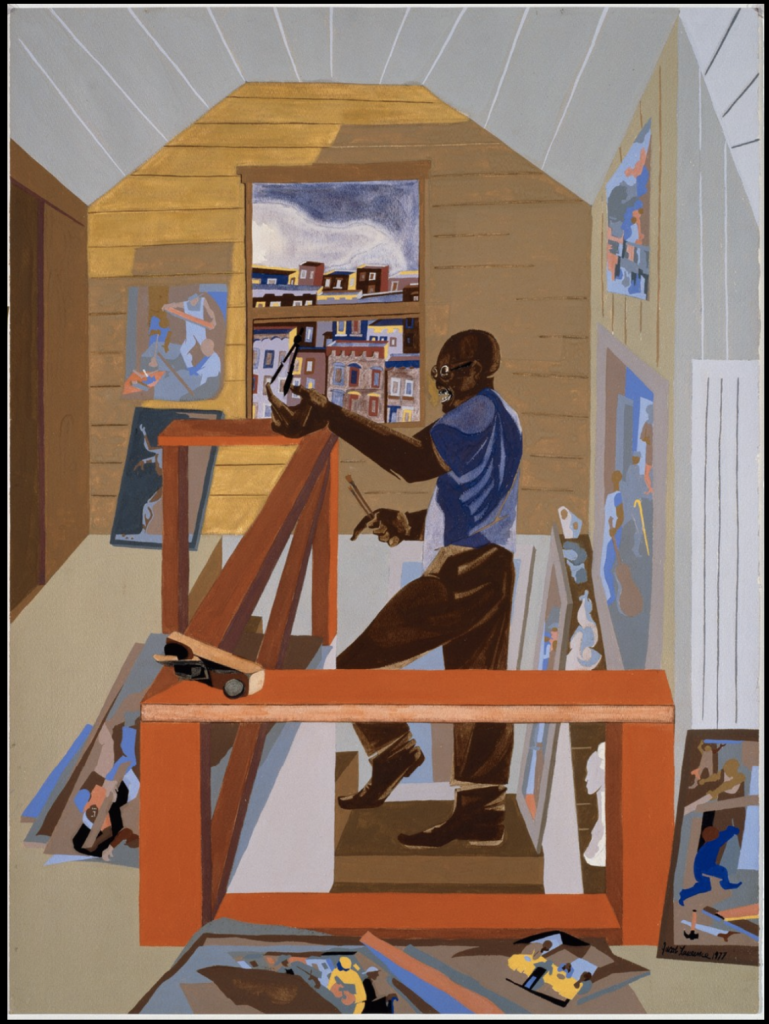

It is interesting, too, that Lawrence decided to keep the poster version of Bumbershoot ‘76, rather than the original and hung it unframed when many framed paintings lean against the studio walls. One major difference between the painting and the poster is the presence of text. The poster clearly identifies the work as being for “Seattle Arts Festival: Bumbershoot ‘76,” while the painting is unlabeled. Perhaps Lawrence enjoyed seeing this direct visual connection between his work and his new city. But while he gives the poster an important placement in his physical studio, it is notably absent from his self-portrait The Studio (fig. 11). The Studio shows Lawrence standing near the top of his staircase, but where Bumbershoot ‘76 should be, there is a blank stretch of wood-paneled wall. Lawrence shows his native Harlem out the window rather than the less artistically important North Seattle neighborhood of Laurelhurst, where the studio was located. But he does not replace the Bumbershoot poster with anything, and its absence in painted representations of the studio emphasizes its proud presence in photographic documentation. This leaves a shadow of ambiguity over understanding how important this early Seattle commission was to Lawrence, personally or artistically.

…

Regardless of Lawrence’s erasure of Bumbershoot ‘76 from later artistic portrayals of his studio, the impact the commission had on his engagement with public art in Seattle remains clear. From 1976 onward, Lawrence was in regular contact with city officials, fielding requests for his participation in exhibitions, commissioning original works, and accepting committee appointments. While the poster fits in with Lawrence’s turn to printing in the 1970s, it stands out for its depiction of open green space found only in a handful of his paintings, out of the hundreds created over his career. Bumbershoot ‘76 is unique for showing community leisure during Lawrence’s period of prolific interest in themes of labor and construction. While his Builders works are often read in terms of labor as a tool for integration, as workers build towards mutual goals, Bumbershoot ‘76 offers a counterpoint: shared space and collective enjoyment of public art are fundamental for building an equitable community. Lawrence’s paintings throughout his working life embodied the goals set out by the City of Seattle’s public arts institutions, but Bumbershoot ‘76 in particular proves that the visual arts can and do enhance mutual understanding between neighbors.

- Peter T. Nesbett, “Jacob Lawrence: The Builders Paintings,” in Jacob Lawrence: the Builders, recent paintings, 5-26, 1998. ↵

- Lawrence’s five-panel series commissioned by the Washington State Arts Commission, George Washington Bush (1973), shows the largely-forgotten story of a local Black pioneer. ↵

- Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy, “Lights Out, Seattle,” The Seattle Times, November. 3, 1996, https://special.seattletimes.com/o/special/centennial/november/lights_out.html. ↵

- Paul Dorpat, “Bumbershoot's Formative Years (1971-1979),” History Link, last modified September 1, 1999. https://www.historylink.org/File/10027. ↵

- Peter Blecha, “Bumbershoot: Seattle’s Arts Festival,” History Link, last modified September 3, 2019, https://www.historylink.org/File/20852. ↵

- Dorpat, “Bumbershoot's Formative Years (1971-1979).” ↵

- Blecha, “Bumbershoot: Seattle’s Arts Festival.” ↵

- “About SAM: Historical Timeline,” Seattle Art Museum, https://www.seattleartmuseum.org/about-sam. ↵

- “Policies & Plans: Public Art Ordinance SMC 20.32.010 Purpose,” Office of Arts and Culture, https://www.seattle.gov/arts/programs/public-art#publicartordinance. ↵

- Blecha, “Bumbershoot: Seattle’s Arts Festival.” ↵

- “Mapping Race in Seattle/King County,” Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington, accessed June 2, 2021, http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/maps-seattle-segregation.shtml. ↵

- Ellen Harkins Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence” (PhD diss., University of Washington, 1987), 179. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” 177. ↵

- Peter T. Nesbett, “Introduction, Jacob Lawrence: From Paintings to Prints,” in Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints, 1963-2000: A Catalogue Raisonné, by Peter T. Nesbett and Patricia Hills (Seattle: Francine Seders Gallery, in association with University of Washington Press, 2001), 9. ↵

- John Blaine to Jacob Lawrence, 6 May 1976, Box 4, Folder 21: Seattle Arts Commission, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/jacob-lawrence-and-gwendolyn-knight-papers-9121/series-2/box-4-folder-21. ↵

- Nesbett, “Introduction, Jacob Lawrence: From Paintings to Prints,” 9. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” 177. ↵

- Wheat, “Jacob Lawrence,” 179. ↵

- Romare Bearden, et al.,“The Black Artist in America: A Symposium.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 27, no. 5 (1969): 250. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3258415. (emphasis added) ↵

- Suzanne Beal, “Art for the Environment: Seattle’s Public Art Embraces Nature in the City,” Public Art Review 20, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009): 66. ↵

- Corinne Murray, “Public Art, Public Funding,” in Accessible Art: A Layman's Look at Seattle's Public Art, ed. Corinne Murray (Seattle, WA: At Your Fingertips, 1990), 3. ↵

- Dorpat, “Bumbershoot's Formative Years (1971-1979).” ↵

- John Blaine to Jacob Lawrence, 1976. ↵

- Pat Fuller to Jacob Lawrence, 9 May 1977, Box 4, Folder 21: Seattle Arts Commission, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/jacob-lawrence-and-gwendolyn-knight-papers-9121/series-2/box-4-folder-21. ↵

- “Who was Jacob Lawrence?” Jacob Lawrence Gallery, School of Art + Art History + Design, University of Washington, https://art.washington.edu/jacob-lawrence-gallery. ↵

- Barbara Thomas to Jacob Lawrence, 9 May 1980, Box 4, Folder 21: Seattle Arts Commission, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/jacob-lawrence-and-gwendolyn-knight-papers-9121/series-2/box-4-folder-21. ↵

- Thomas’s website confirms that she worked “in agencies such as the Seattle Arts Commission and Bumbershoot” and went on to work in public arts administration, along with being an active artist herself. “Barbara Earl Thomas,” Barbara Earl Thomas, https://barbaraearlthomas.com/barbara-earl-thomas/ last modified 2021. ↵

- Richard Andrews to Jacob Lawrence, 17 July 1981, Box 4, Folder 21: Seattle Arts Commission, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/jacob-lawrence-and-gwendolyn-knight-papers-9121/series-2/box-4-folder-21. ↵

- City of Seattle, “Arts E-Museum: Jacob Lawrence,” Office of Arts and Culture. Accessed May 30, 2021. https://seattlearts.emuseum.com/advancedsearch/Objects/people%3A%22jacob%20lawrence%22/images?page=1 ↵

- John Blaine to Jacob Lawrence, 1976. ↵