11 Hiroshima

Jacob Lawrence, War, and Activism

Kira Sue

Abstract

In order to attempt a serious understanding of Jacob Lawrence’s Hiroshima series of 1983, the characterization of Lawrence as an apolitical artist must first be questioned through a discussion of the ways in which Lawrence’s work has been praised for this quality and the artist’s increasing connections to activism from the 1960s on, such as in his depictions of the civil rights movement. To contextualize the Hiroshima series in Lawrence’s oeuvre, this essay will discuss the artist’s previous work on the topic of World War II in his Coast Guard and War series of 1943-1945 and 1947 respectively, as well as the existing scholarly treatment of these series. An exploration of his commitment to activism, combined with the historical context of relevant events such as the Three Mile Island disaster of 1979, provide possible motivations for Lawrence to return to the topic of World War II 36 years later.

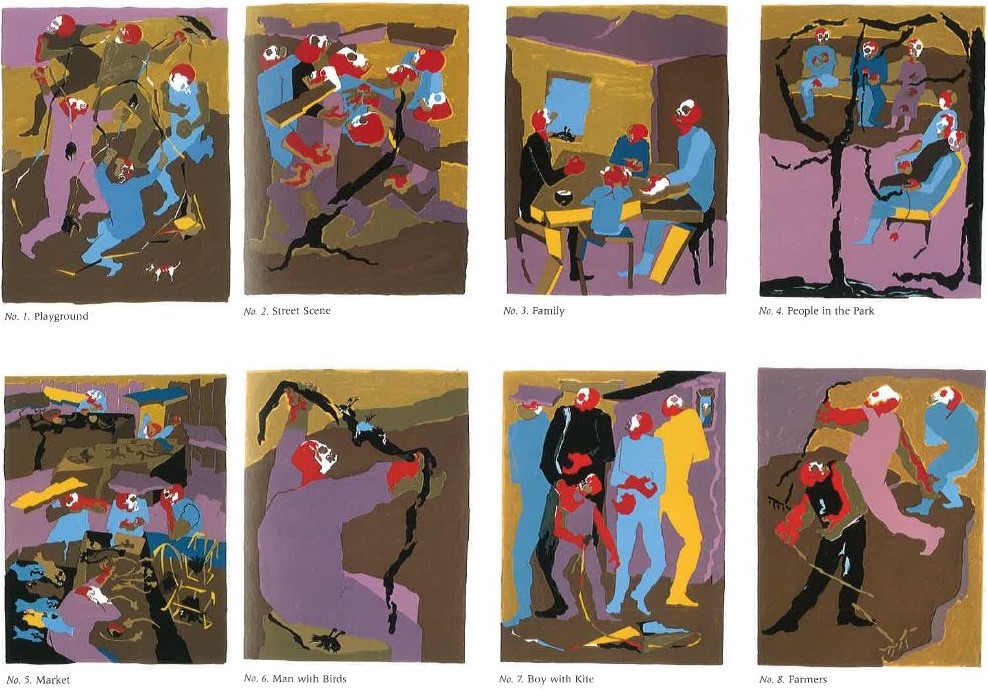

Jacob Lawrence’s Hiroshima series of 1983 is one of the many understudied works of Lawrence’s later career, perhaps because of its untidy fit within the accepted narrative surrounding Lawrence, his career, and his politics (fig. 1). Despite an unfortunate scholarly habit of discussing his long career myopically through the lens of his Harlem youth, Lawrence’s practice and approach to his topics were anything but static. In order to approach this series seriously, a complete reevaluation of the overdetermined reading of Lawrence as an apolitical artist is necessary. The Hiroshima panels are by far the most graphic depictions of violence in his oeuvre: they are shockingly visceral, the figures’ exposed skulls clearly visible. Nevertheless, at the time of their publication in the reprint of John Hersey’s Hiroshima, they were an unequivocal success. The book completely sold out and generated great acclaim. When placed into the context of Lawrence’s work on the subject of World War II and his increasing interaction with activist movements since the 1960s, it becomes clear that the Hiroshima series is not without precedent, but is rather the culmination of Lawrence’s lifelong commitment to contributing to justice through his artistic practice.

Early Career

“There is little or no hint of social propaganda in his pictures, and no slighting of the artistic problems involved, such as one finds in many of the contemporary social-theme painters.”[1] This is how Alain Locke, one the most distinguished representatives of the Harlem art and intellectual scene, described Jacob Lawrence’s work in 1940. Locke was instrumental in launching the young artist’s career. He wrote letters for funding, corresponded with gallerists, and produced some of the first serious writing on Lawrence’s work, positioned within an essay entitled ‘Naïve and Popular Painting and Sculpture. Art historian Lizetta Lefalle-Collins has argued that this early criticism “sealed the context for Lawrence’s work” within Harlem and discourses of primitivism and the “naive,”” for instance in favorable critical reviews that praised his “poster-like bright colored scenes” and “the cut-out kindergarten gaiety of his protest.” These ostensibly positive impressions may raise alarm bells for contemporary readers or those already familiar with Lawrence, and for good reason. As Lefalle-Collins has shown, these back-handed compliments from white and black critics alike would come to dog Lawrence’s entire artistic production, a framework for understanding his work that would remain “the most overarching and enormously complicated issue of his career.”[2]

Though Lefalle-Collins focuses on the problem of Lawrence’s ascribed primitivism, taken in conjunction with Locke’s focus on ‘propaganda’, it becomes apparent that the two ideas are linked. Indeed, this is visible in the above comment where the “kindergarten gaiety” is explicitly linked to and undermines Lawrence’s “protest.” These characterizations of Lawrence were anything but accidental. Contemporary scholarship acknowledges that critics often preferred to ignore the realities of Lawrence’s artistic training and intellectual connections in favor of a narrative of unspoiled artistic inspiration. Though it may be surprising given their mutual goal of elevating Black artistic production, Locke’s treatment of Lawrence, such as his use of the word naïve, was more intentional yet. Black artists, critics, and intellectuals were aware of white interest in the ‘primitive,’ and often cannily exploited this ignorance.[3]

Context is everything. For example, the first of Locke’s above quotes was taken from a letter written on behalf of Lawrence to the Julius Rosenwald Fund with the intention of attaining a substantial scholarship for the young artist. This context and monetary incentive casts Locke’s words in a completely different light. The comment on “propaganda” can be read as reassuring a conservative potential benefactor that Lawrence creates ‘appropriate’ art, while the emphasis on “artistic problems” center’s Lawrence’s identity as a Modern artist. This assertion of Modernism is important as in the 1940s and ‘50s artistic discourse was almost singularly focused on formal experimentation, and works not fitting within the ascetic Modernism framework were at risk of critical dismissal.[4]

Early writing about Lawrence by Locke and others is often invoked in scholarship sans this deeper contextualization, for instance in connection with assertions about Lawrence’s humanism. Art historian Lowery Stokes Sims’s analysis of the artist’s Builders works is one example: she cites Locke to support her argument for Lawrence as a humanist, universalist, and insider.[5] Sims’s focus is the artist’s “conceptualization of form,” and in concentrating on the issue of abstraction and style, questions of the power dynamic between a young, Black, working-class artist and his mentor and a wealthy, largely white institution looking for suitable recipients of their charity are left unexplored as they do not pertain to her particular point, nonetheless, it demonstrates the possibility for misinterpretation where context is not included. Art historian Patricia Hills also uses Lawrence’s humanism to posit that he, “did not feel himself at war with America” and “took the humanist view.”[6] These statements, especially the bold claim regarding what Lawrence may or may not have felt, come across as dissonant when contrasted with the evidence of Lawrence’s engagement with activism present in her own chapter. It is worth noting how humanism often appears alongside claims of Lawrence’s apolitical nature, and how it may serve to soften or deflect uncomfortable truths.

The frequent linkage of humanism and Lawrence’s supposedly apolitical nature is reminiscent of how the artist’s work was often pacified in presentation and discussion. This making-safe was likely initiated originally by Lawrence and his mentors, as shown above, to help the young artist attain the financial resources he would need in order to succeed. However, this safe image was then co-opted by critics and a wider white audience once his art world stature began to rise. Racial tensions were high throughout the 20th century, and artistic institutions began to face more pressure from increasingly organized Black artists and critics to show their work. As so often happens when minorities fight for entrance into spaces historically restricted through the structures of white supremacy, one individual may be selected by the majority as a concession, a process commonly referred to as tokenism. Lawrence was the first Black artist to be represented by a mainstream New York City gallery and shortly thereafter, was the first to achieve such a high level of success and recognition. Throughout his career Lawrence would often be the first Black artist, or the first Black person, invited into various institutions, committees, and roles. This was no accident. Severe racial turmoil was a constant across the artist’s 60-plus year career, from the red summer of his youth to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and beyond. As an artist who was ‘made safe’ – that is, popularly perceived as not openly hostile to institutions, the government, or whites – Lawrence was often used as an asset and as a balm against this wound, as in Portland, Oregon in 1943 when the Migration series was deployed to help quell tensions between white dockworkers and recently arrived Black workers. Though this issue of the Safe Jacob Lawrence can be difficult to detect definitively, it is worth remaining aware of its specter when considering scholarship on Lawrence as well as his treatment by institutions.

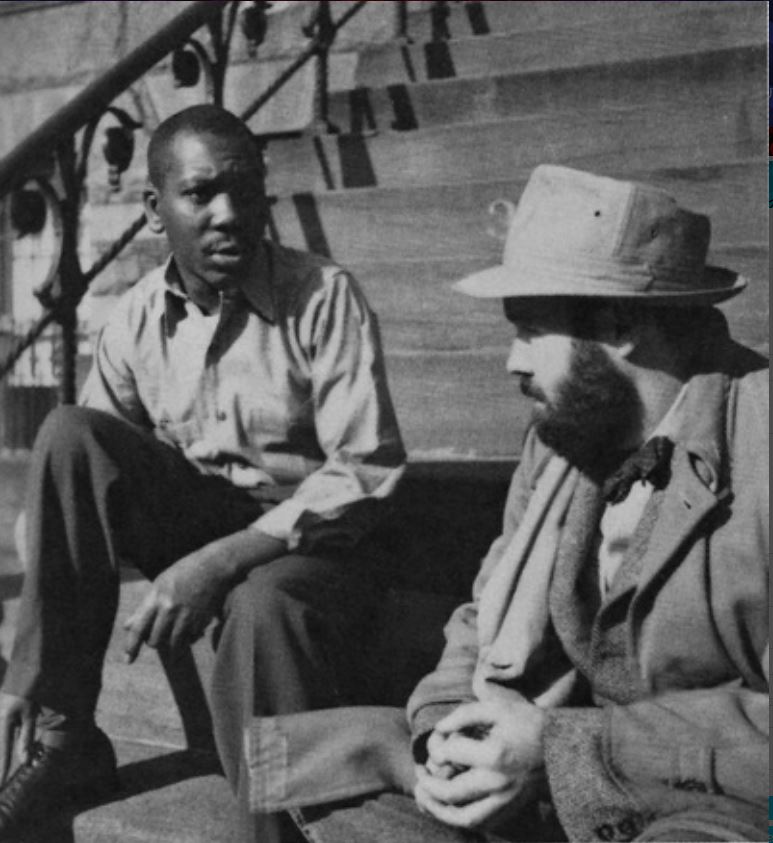

After this initial strategy was launched by Locke, Lawrence had many incentives to maintain it, or at least, not to actively dispel it. During his early career he was largely sustained by government work and charitable organizations. As a young artist, roughly between 1936 and 1939, Lawrence worked in the Civilian Conservation Corps, and later, for the Works Progress Administration. This work was financially indispensable to his family, and also meaningful to him personally: Lawrence often referred to his time in the WPA as his education.[7] Shortly thereafter he was assigned to the Coast Guard from 1943 to 1945, during which he experienced what he described as the “best democracy I’ve ever known” aboard the Sea Cloud (fig. 2).[8] Over the first 10 years of Lawrence’s career, he was often employed by the U.S. government, and from these comments, it seems to have been a mostly positive experience. This is to say that Lawrence depended on a working relationship with the government for his own material and often, artistic, well-being. It would not have been in his interest to alienate this valuable resource.

The second source of Lawrence’s finances, scholarships and fellowships from charitable institutions, is a fascinating story. Lawrence still needed to remain acceptable and avoid alienating important resources, but his financial connections also reveal involvement with leftist political groups, some of them quite radical. Beginning in 1937 with a two-year scholarship to the American Artists School, associated with both socialist and communist schools of thought, Lawrence was rarely without some form of institutional sponsorship. In 1940, and again in 1942, Lawrence would apply to and receive the aforementioned fellowship from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, a paternalistic foundation dedicated to the ‘betterment of mankind.’ It may be widely known that Lawrence was the frequent recipient of these types of awards, however, their size and significance has not been adequately acknowledged. Early in Lawrence’s career he received a series of awards valuing between $20,000 and $50,000, adjusted for inflation.

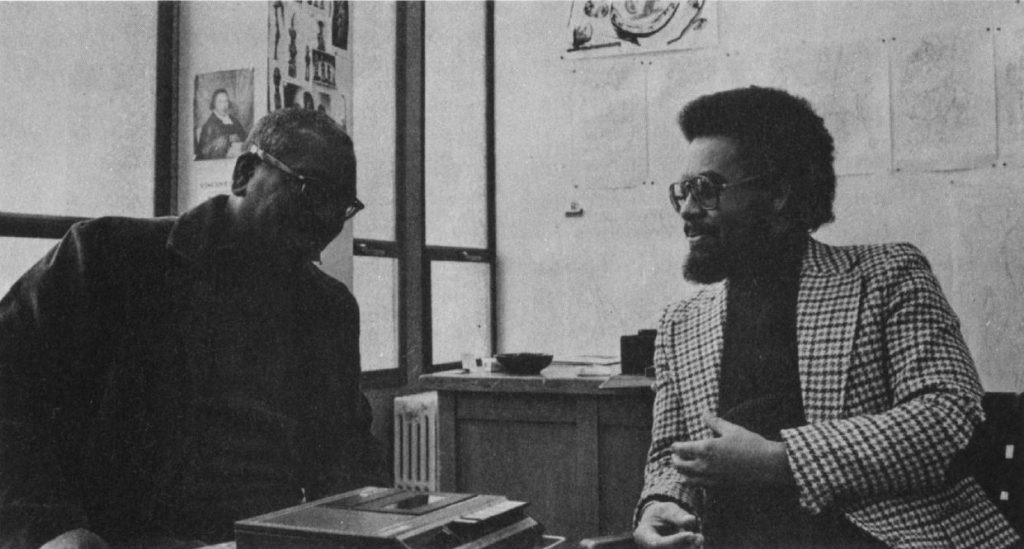

Some of these financial connections had long durations such as the Rosenwald Fund who, in addition to the scholarship, also likely paid Lawrence’s salary during his time at Black Mountain College, and in 1954 Lawrence was referred to a fellowship by his friend, Jay Leyda, curator at MoMA and a communist (fig. 3).[9] In short, Lawrence had enormous incentives not to do anything that would make him less appealing to scholarship selection committees, especially considering that he was funded alternately by left and right-wing foundations.

Later in his career Lawrence would encounter negative incentives from the U.S. government to maintain his semblance of neutrality. The McCarthyism of the early 1950s would threaten artists and progressives across the United States, including some that Lawrence knew, reaching its pinnacle in the House Committee on Un-American Activities of 1954. Between 1961 and 1964 both Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence were intermittently hassled over their trip to Nigeria, with the government even going so far as to take measures to deny them access to lodgings before retreating under threat of a lawsuit. Even without provoking attention, the Lawrences faced the threat of unwanted scrutiny. This likely explains some of Lawrence’s more adamant refusals of involvement with politics. In 1952 Lawrence refused an invitation by the government to improve America’s reputation by lecturing abroad.[10] This refusal has been read as a veiled critique of American democracy, along with the Struggle series completed during this time about which Richard Powell states, “Lawrence concealed [his] contempt for American chauvinism and intolerance with more subtle tactics: by revealing the absurdity of certain American symbols via modernist painting techniques and by presenting the often complicated truths of their subjects within a nonliteral framework.”[11] It could also be viewed as a strategy of self-protection, a refusal to collaborate with the government on any project even vaguely political. Lawrence made a similar refusal in 1980 to President Carter when invited to the White House to be honored for painting pictures protesting racism. Lawrence objected to the use of the term protest, possibly feeling that it was too nakedly political.[12]He would have been far from the only Black artist during this time to make political art while remaining indirect enough to avoid confirmation by either the press or government of his views.[13] Before 1950 however, Lawrence’s most significant experience with the government was his Coast Guard series.

Wartime

To begin analyzing Jacob Lawrence’s Word War II subject matter, The most substantial scholarly studies of Jacob Lawrence’s World War II subject matter are John Ott’s 2015 article in American Art about the Coast Guard series, and a recent dissertation by Robert Ribera, Between Patriotism and Pacifism, which connects Lawrence’s three series on World War II. Both authors note the change in tone between the Coast Guard and War works, which gradually become more somber and meditative about the costs of war, and less focused on the opportunities military service presented for racial integration. This important shift in Lawrence’s perspective set the stage for his increasingly condemning portraits of war throughout his career. In Battle Station MoMA, Ott argues that Lawrence’s initial optimism in the Coast Guard series stemmed primarily from his posting aboard the first integrated ship in the navy, the Sea Cloud, under the progressive Captain Charlton Skinner. This context suggests that Lawrence was less a supporter of war itself than of the opportunities it presented for Black Americans, exemplified by the well-known double v campaign in the press in which the fight against white supremacy at home was linked to the fight against Nazi ideology abroad.[14] Only one of the Coast Guard paintings veers into the territory of glorification, The Big Gun, and even then, the weapon is not shown in action but is more akin to a prop in a genre scene of life aboard a military ship. It is also clear that Lawrence and Skinner were close, Skinner being the subject of one of Lawrence’s few portraits. Based on the circumstances, it seems that the two men worked together to further a shared agenda for racial integration beginning with Skinner’s promotion of Lawrence to a public relations position where he was encouraged to paint.[15]

With the War series of 1946-47, Lawrence turned his gaze to the costs of war rather than the opportunities it presented. His transfer to the General Wilds P. Richardson towards the end of his naval career may have contributed to this shift in tone. Lawrence described the experience in this way:

I was on a troop transport ship which was a very sad experience, something that will remain with me for the rest of my life. We would go overseas carrying 5,000 troops and we would come back a hospital ship. I’m sure that many of these cases are in the hospital today – basket cases. I’ll always remember the physical and psychological damage.[16]

Lawrence obviously took the tragedies he witnessed during this time very hard. His discussion of the “basket cases” and focus on psychological damage may even reveal a resonation with his own struggles with mental health. Regardless, it marks a stark contrast from the positive terms in which Lawrence discussed his time aboard the Seacloud. The War series also presents a blending in focus of the military experience of war and the civilian experience of war, as Lawrence himself explained:

I attempted to portray the feelings and emotions that are felt by the individual – both fighter and civilian. A wife or a mother receiving a letter from overseas; the next of kin receiving a notice of casualty; the futility men feel when at sea or down in a foxhole just waiting, not knowing what part they are playing in a much broader and gigantic plan.[17]

This trend is strengthened in the Hiroshima series which presents only the civilian experience, there is no visible evidence of a military presence except for the effects on the human body.

The Breaking Point

The violence of the 1960s played out in the clash over civil rights appears to have been a breaking point for Jacob Lawrence, pushing him out of his comfort zone and into more clearly political expressions. As I have argued, Lawrence was never a truly apolitical artist and consistently made work that functioned as political commentary, most recently in the Struggle series. However, his work produced in the ‘60s crossed a line.

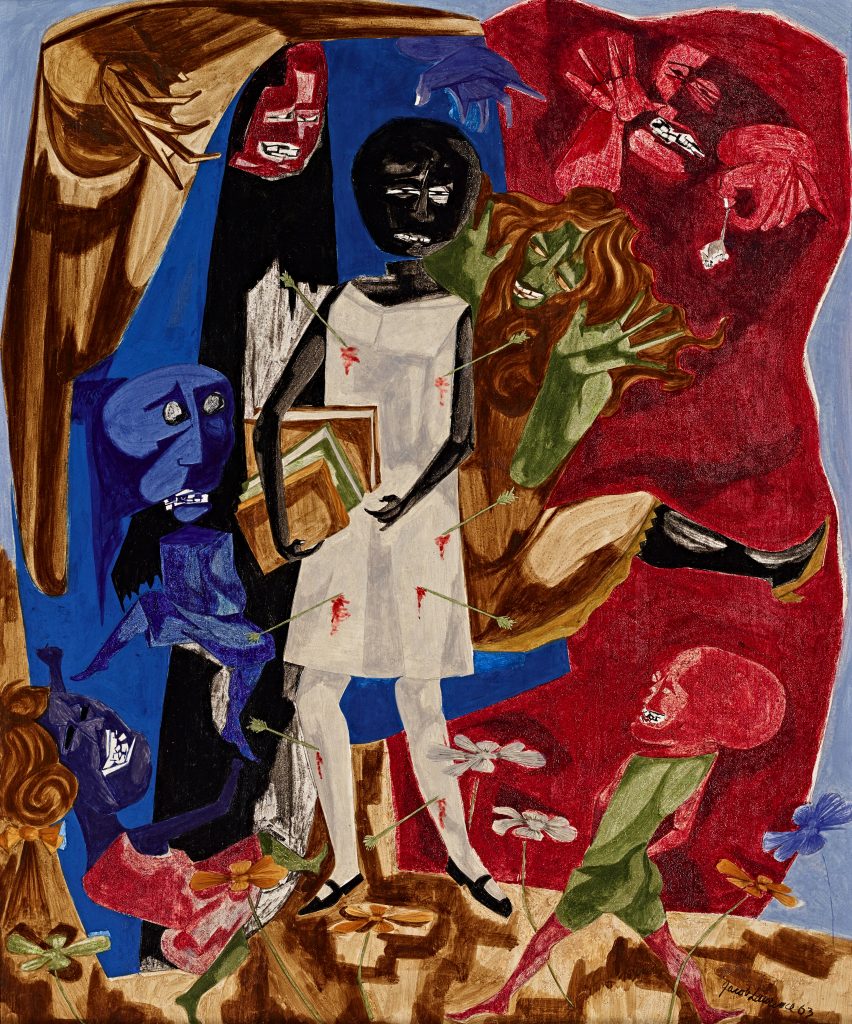

The starkest example of this is the 1963 painting Ordeal of Alice, in which menacing demons ‘demons’ loom over the young girl (fig. 5). Lawrence explained the need for the figures by stating that they represented an ugly situation which could only be expressed through distortion, a statement to keep in mind when examining Hiroshima, with its vibrating outlines. However, the most significant change in the civil rights works is the fact that they often depict specific moments and some compositions are even based on press photos, leaving behind the protective distance and identity of historian and engaging directly with the present moment. Alice is based on the famous photograph of Elizabeth Eckford attempting to enter a school that is being desegregated, white students’ twisted masks of hatred visible all around her, while American Revolution called to mind photos of the attack dogs that had been recently unleashed on crowds in Birmingham.[18] Confrontation on the Bridge also shows a specific interaction between Martin Luther King Jr. and the police blocking the bridge to Birmingham.[19]

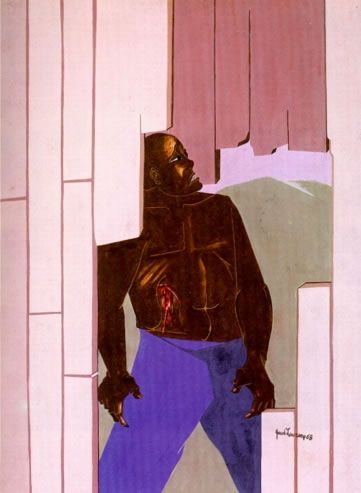

Wounded Man, while not as clearly linked to a specific event, is the most graphic depiction of violence yet in Lawrence’s career, with the man’s side wound clearly foregrounded, his wound gushing blood on display (fig. 6). Alice too, is unusually violent with bloody arrows sticking out all over her body, especially given that the subject is a child.

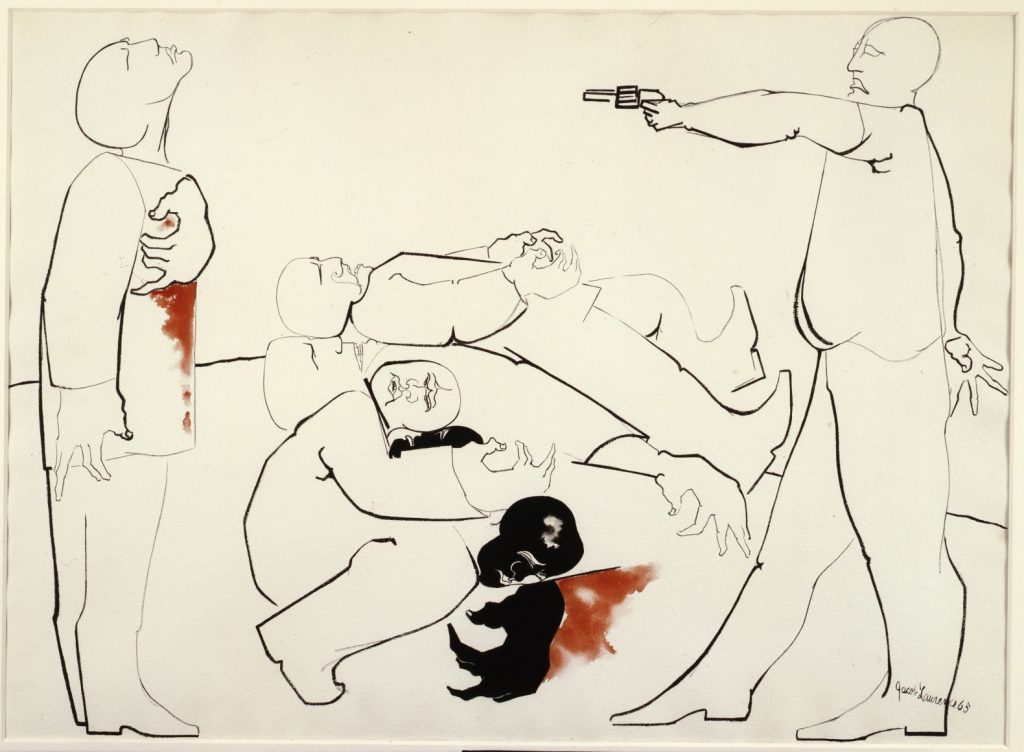

Struggle II and III created during this time also feature blood prominently (fig. 7). They all do so in a markedly different manner than past images as well. Though Lawrence had shown blood before, such as in the Struggle series of the ‘50s, it tended to be used abstractly, often emerging from nowhere at all and scattered around the picture plane. In the ‘60s, the blood was coming from real people with real wounds. As Lawrence became more disturbed by contemporary events, it seems he was compelled to impress upon his audience the gravity of these events and the toll they were taking on real bodies.

Lawrence’s activism increased off the canvas as well as on. He took on leadership roles; in 1957 he served as the president of the New York Artists Equity Association, of which he was a founding member, and in 1963 as the President of the Art Committee of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Lawrence’s involvement with the SNCC has been yet another point of misinformation in scholarship, with scholars citing SNCC frustrations with Lawrence and implying that he did not believe in their mission and that the two were incompatible.[20] In 1976 Lawrence would again co-found an organization focusing on issues of diversity in the arts, the Rainbow Art Foundation, which aimed to promote the work of underrepresented minorities. Lawrence would also come to be associated with activist groups, such as in his cooperation with Artists’ Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America in 1984. But according to Lawrence, by far the most important activism of his career can be found in his paintings, as he told Clarence Major in 1977:

Major: [Marquez] said that if he had any commitment to revolution it had to be through his work. He felt that the very act of writing was a revolutionary act.

Lawrence: Oh, I would agree with that. Sure, as an artist, I would hope to make a contribution. With my commitment to my fellow man, I would hope to make some commitment through my art.[21]

This quote is the key to understanding Lawrence’s activism. He saw his art, and by extension his work in the art community, as a concrete and meaningful way to make the changes he wanted to see in the world. His art is his activism, or his contribution, as he calls it.

Hiroshima, Again

In 1970 Lawrence accepted a professorship at the University of Washington that would last until his retirement in 1986 (fig. 8). His longtime commitment to painting his surroundings, what he knew, and the experiences of those around him did not waver with the relocation out west. Given this approach, Lawrence’s choice to take on the Hiroshima series might be seen in part as a product of his new environment. The population of Asian Americans, and in particular Japanese Americans, was much higher in Seattle than in New York City, proportionally. Unfortunately, one of the reasons for this higher concentration of Japanese Americans is the location of the Japanese internment camps on the West Coast. Lawrence’s interest in the people and history around him may have prompted him to explore a related topic, though there is no explicit evidence linking Lawrence’s move to Seattle or relationships with Japanese Americans to his decision to depict Hiroshima.

However, Lawrence’s relocation combined with the current events during his Seattle period may have brought Hiroshima to mind, specifically, the Three Mile Island disaster of 1979. The disaster, involving a partial meltdown of a nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania, remains the most devastating nuclear accident to occur in the United States. The event was a catalyst for anti-nuclear activism and prompted a demonstration of over 200,000 people in New York City at one point. A proliferation of anti-nuclear artist activity occurred as well with groups such as Artists for Nuclear Disarmament, as well as many artists tackling the subject independently. This event occurred in the middle of the 1970s and ‘80s, a period afflicted with widespread Cold War anxieties and an “all-pervasive and universalizing notion of the atomic threat” in which many Americans were genuinely worried about the threat of human extinction due to nuclear war.[22]

In February 1983 the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians convened to investigate the Japanese internment camps, supposed justifications for their formation, and impact on Japanese Americans unanimously concluded that the internment camps were unjustified and caused mass harm both material and psychological, and recommended that reparations be made. While this verdict was received well by both the public and government officials, subsequent attempts to actually provide reparations failed repeatedly through 1988. Nevertheless, it brought renewed attention to the topic of the Japanese internment camps, a trauma the nation seems perpetually in danger of forgetting. Though Lawrence had already selected the topic of Hiroshima by 1982, he did not finish the paintings until 1983, so it is not impossible that the announcement factored into his process.[23] Regardless, it contributed to the environment in which Hersey’s reprint and the Hiroshima series were received.

After attaining a stable position and income as a professor at the University of Washington and spending the 1970s relatively peacefully in pedagogical pursuits, Lawrence was once again compelled to “make a contribution” through his art. Though in 1981 Lawrence sent his regrets to the Limited Editions Club as he did not feel he could take on a book illustration project at the moment, by 1982 Lawrence had apparently changed his mind. In a letter from the Limited Editions Club from August of that year, Sidney Shiff expressed his pleasure at meeting the Lawrences in person in New York and coming to an agreement on Hiroshima.[24] What could have compelled this change of course? On June 12, two months earlier, the largest political demonstration in American history took place against nuclear weapons and the Cold War with over one million people filling Central Park. Shiff’s letter says they met in person that summer, so it’s even possible that the Lawrences were in New York during the protest. In any case, Lawrence was a historian at heart, and history was unfolding that summer. It would have proved nigh irresistible for Lawrence not to chronicle the movement.

And so it was that 36 years after Lawrence had last painted on World War II, he picked up his brush again. Since the War series Lawrence had been moved to complete two serious forays into political art with the Struggle series and the works completed during the Civil Rights Movement era, with Lawrence’s criticism becoming more pointed in the second set of works. He returned to the theme of World War II as an artist of the highest echelon, an accomplished professor, and an experienced activist. Lawrence had gone from the soldier’s perspective in Coast Guard to the family at home’s perspective in War. In Hiroshima, Lawrence at last turned his compassionate gaze to the ‘enemy.’ The subjects of the series are often emphasized in scholarship as universal, and not a specific representation of the Japanese at all, and this is true to a certain extent. Lawrence did state that he made no attempt to render the Japanese features and that the series was a portrait of “man’s inhumanity to man.”[25] But however universally the images are viewed, it remains fact that the atomic bomb has only been dropped on one country and one people, and these images are placed alongside highly personal descriptions of the impact of the bomb on those people. Lawrence may not have created an overly specific depiction because he did not need to, these images were created to accompany this text. This universalism could just as easily be contextualized by the political climate of the 1980s and its extinction fears as the humanism that it is typically ascribed to. Given the publishing of the series the same year as reparations for Japanese Americans were recommended and denied, it is also possible to see a very intentional representation of Japanese subjects. In light of this chapter’s questioning of assumptions about his politics, contextualizing of his activist works within his career as a whole, and exploration of his possible motivations, a possibility is opened for viewing Jacob Lawrence as a complex and dynamic visual activist.

- Lowery Stokes Sims, “The Structure of Narrative: Form and Content in Jacob Lawrence’s Builders Paintings, 1946-1998,” in Over the Line: the Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, ed. Peter T. Nesbett (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 214. ↵

- Lizzetta Lefalle-Collins, “The Critical Context of Jacob Lawrence’s Early Works, 1938-1952,” in Over the Line: the Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, ed. Peter T. Nesbett (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 122, 123, 134. ↵

- Ibid., 122. ↵

- Ibid., 121. ↵

- Sims, “The Structure of Narrative,” 213-214. ↵

- Patricia Hills, “Jacob Lawrence’s Paintings during the Protest Years of the 1960s,” in Over the Line: the Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, ed. Peter T. Nesbett (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 186. ↵

- Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “The Education of Jacob Lawrence,” in Over the Line: the Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, ed. Peter T. Nesbett (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 100. ↵

- John Ott, “Battle Station MoMA,” American Art 29, no. 3 (2015): 74. ↵

- Peter T. Nesbett, Michelle DuBois, and Patricia Hills, Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 28-38. ↵

- Richard J. Powell, “Harmonizer of Chaos: Jacob Lawrence at Midcentury,” in Over the Line: the Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence,ed. Peter T. Nesbett (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 163. ↵

- Ibid., 160. ↵

- Hills, “Jacob Lawrence’s Paintings during the Protest Years of the 1960s,” 189. ↵

- Powell, “Harmonizer of Chaos,” 149. ↵

- Ott, “Battle Station MoMA,” 66. ↵

- Ibid., 66. ↵

- Ibid., 74. ↵

- Ibid., 73. ↵

- Hills, “Jacob Lawrence’s Paintings during the Protest Years of the 1960s,” 181. ↵

- Deborah Wye, Committed to Print: Social and Political Themes in Recent American Printed Art, (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988), 39. ↵

- Hills, “Jacob Lawrence’s Paintings during the Protest Years of the 1960s,” 186. ↵

- Clarence Major, “Clarence Major Interviews: Jacob Lawrence, The Expressionist,” The Black Scholar 9, no. 3 (1977): 20. ↵

- Kyo Maclear, Beclouded Visions: Hiroshima-Nagasaki and the Art of Witness, (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999), 93-94. ↵

- Professional Files, Box 23, Folder 31, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers, 1816, 1914-2008, bulk 1973-2001. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- Sidney Shiff to Jacob Lawrence, April 14, 1981. Box 23, Folder 31, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight papers, 1816, 1914-2008, bulk 1973-2001. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- Paul J. Karlstrom, “Modernism, Race, and Community,” in Over the Line: the Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, ed. Peter T. Nesbett (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in association with Jacob Lawrence Catalogue Raisonné Project, 2000), 241-242. ↵