12 Miguel Symonds Orr on R. Buckminster Fuller

Miguel Symonds Orr is an ecological designer committed to the movement(s) to shift society in more democratic, egalitarian, and ecological directions. They are studying ecological design at the University of Washington through programs in the College of Built Environments and the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. Their focus is on the Nch’i-Wána Plateau region of Washington State East of the Cascades, which they call home.

Buckminster Fuller (1895 – 1983) was an ecological designer and visionary thinker, known for concepts he espoused such as ephemeralization and tensegrity, and projects he designed such as the Dymaxion house and, most famously, the geodesic dome. He taught summer programs at Black Mountain College in 1948 and 1949.

Preface:

This letter is written as a message to R. Buckminster Fuller from a fictional group of his followers who have decided to change their course away from some of his guidance.

Dear Captain R. Buckminster Fuller,

It is with a heavy heart that I inform you that prospects on Spaceship Earth are looking grim, which you were able to sense during your last years aboard[1]. The emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, which contribute to the overall warming of Earth’s temperatures, continue unabated[2]. Beautiful, biodiverse places on Earth are pillaged and stripped of their natural beauty to support only the profits of a few in a design mindset that is short-sighted and unsustainable. Plastics, despite the technological benefits they bring, are polluting oceans and waterways and harming more and more wildlife[3]. We seem to be on a spaceship steered by a greedy few who are crashing our common prospects against the rocks in pursuit of the dollar. And while your technological inventions have had a great impact, and green technology is expanding, an overall shift to green technology which would slow our disastrous route has not occurred.

An analysis of our present conditions, informed not only by the findings of the sciences but by the philosophical works, structural interrogations, and historical accounts of many with diverse viewpoints, including those whose viewpoints are too often overlooked, especially Indigenous peoples, has led us to make a change in our organization. We will no longer refer to the planet that is our common home as ‘Spaceship Earth’, and we no longer intend to be the captains of it. Instead, we see the Earth as a beautiful, bountiful, unique, and complex organism which provides for our needs if it is respected and listened to. Although this is a change from your direction, it follows aspects of your thinking, such as your constant pursuit of knowledge of the principles of the universe and application of them.

Although you have seen humanity as on a linear path from uneducated to learned in which we have only recently gained the potential to provide for all humans[4], many indigenous peoples throughout the world have lived on this planet for generations without despoiling its resources. They often saw the Earth as a relative, not simply a collection of resources to be measured and accounted for[5]. Their beliefs helped to keep their society in positive relationship with their local ecology, so we believe we should listen to their viewpoints for the good of our planetary home. In fact, indigenous peoples currently protect eighty percent of biodiversity[6]. While we are certain that the principles of design you researched and applied to create buildings, such as the power of the triangle in structures and the lightness and strength of aluminum, will be important for the future, we aim to balance this perspective with the technological genius inherent in the ecological designs of indigenous peoples.

Furthermore, we wish to distance ourselves from military terminology, since the United States military and militarism the world over is a major contributor to ecological devastation. In fact, the US military is responsible for 59 million tons of CO2 emissions in 2017, over 10 million tons higher than all of Sweden’s CO2 emissions[7]. We know that your experience in the military was very formative to you, and we believe that we need to move beyond militaristic ideas but retain rigorous research and clear organizational structures, positive elements you recognized in the military. Although the military was one of your biggest clients[8], we no longer wish to support it with our technology. As you said, the military is an instance of “extraordinary technology, beautiful science… reduced as to work to destruction”[9].

We are continuing with your mission to educate as many people as possible in the sciences and in design, but are adopting a more localized approach. While design experts are vital to the future of our world, there are limitations to our previous model, in which we taught people generalized principles without focusing enough on applying those principles to their local environments. Design experts from afar will never be able to design as well as design experts who are in touch with their local ecologies. However, we will need more than education to actualize the changes we need.

In 1968, you said ‘if humanity succeeds, its success will have been initiated by inventions and not by the debilitating, often lethal biases of politics’[10]. However, many green technologies like those you’ve dreamed of have been or are being created, such as structures printed by machines from the Earth under our feet[11] and plastic-like materials made out of fungi[12]. Solar photovoltaic panels are more efficient than ever[13], and great strides are being made in designing buildings that gather more energy than they use[14]. The mere existence of these technologies has not led to a shift; instead, because of political motives, our material resources continue to be used in foolish and harmful ways. Your recognition that politics are often subservient to production[15] rings true. In our current systems, politicians are paid by those who control and profit from production, and therefore our production systems are ratified and protected by political systems. This is why ecological technologies have not yet displaced traditional extractive methods.

Therefore, we have decided that we need to change the political system that protects harmful production methods, despite your belief that engaging in politics is futile. We must engage in a politics that puts production and ecological decisions in the hands of all in local communities rather than a privileged few who benefit from ecological destruction. Our ideas about the form of this politics are much inspired by the work of Murray Bookchin, a contemporary of yours who spoke at the Toward Tomorrow Fair in 1978, an event you also presented at[16]. We believe you were rightly skeptical of politics since electoral politics often empowers small groups of people who work within systems which devastate the earth while meeting the economic needs of only a select few. Bookchin called this kind of politics ‘statecraft’[17]; instead, we intend to pursue a politics that will empower all.

We have already mentioned that we are intending to empower designers in local environments, not just a centralized group. We think this is vital for the future of the planet. Your mass-produced designs included many genius technological advancements in methods which make production more energy-efficient and less resource-intensive; however, the resources to transport mass-produced goods remains significant. Luckily, makerspaces, locations in which various machines are located in communities for local production, are becoming more prevalent. Advancements in 3D printing technology, in which one can create a design with a computer and actualize it through the use of various machines which turn materials into forms, are making it easier and easier to produce locally. We also recognize that ecological design cannot be centralized like yours often was because the materials and constraints of environments differ. For example, in hot and sunny environments, houses must be designed to protect residents from the sun in hot seasons and to be well-ventilated. However, in cold environments, houses must be designed to protect residents from the cold and capture as much solar energy as possible. Centralized designs like your Dymaxion house[18] cannot respond to all of these environments despite their many important strides in design.

To democratize design, we intend to educate all who want design skills through makerspaces in every community and free design classes held by our organization. We will all be co-designers of our common home, rather than a small group of designers designing for the rest. However, we recognize the value in designs which are created in one location and adapted to many other locations. A good example is the Via Binarii project by unfold.be, in which a digital design file for a teapot which is used in machines to print three-dimensional objects was sent to different makers around the world. Makers in each location adapted the design to their personal goals, sometimes linking it to design histories in their locations[19]. We will follow a similar pattern, creating designs together and working with others so they function in diverse environments.

Another important principle you recognized is the ability to recycle or reuse materials indefinitely[20]. Unfortunately, the sheer quantity of materials that have been discarded and are now being created is so massive that extra creativity is needed to find uses for some materials. Our collective aims to focus on reuse and recycling in our designs. One of our design collective members, Miguel Symonds Orr, created a hand-sewn piece primarily from used or repurposed materials representing the local ecology and production of the Nci-Wana plateau region of Central and Eastern Washington State. This design showcases our principles of reuse in its construction and attention to local environments in its theme.

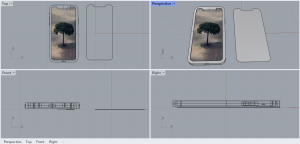

Research into the ecological costs of various materials have led us to move from a dependence on metals to a greater focus on local materials that take less energy to extract and build with, such as wood and even earth itself. While metals have many strengths which you recognized, such as aluminum’s high tensile strength[21], the ecological cost of mining for them and producing with them is too high to justify extensive use. Indigenous peoples in various parts of the world have built comfortable houses that mesh with their local environments from only the materials around them; learning from this is necessary for the future. The principle of ephemeralization that you often spoke of, in which technology is on a route to accomplish more and more with fewer and fewer resources[22], seems understandable given the last few hundred years of industrial society, but in the current political system, that efficiency does not lead to gains for everyone or even less extraction, because economic growth often leads to only more extraction. New high-tech products such as cell phones and computers, which take a heavy ecological toll to produce, are produced every year. Miguel, mentioned earlier, created an art piece to encourage others to think of the connections between constant production and ecological devastation. The design is a representation of an iPhone 11, a new computer technology, created in a 3D modeling program. Within the phone is an image of a lone tree in a deforested area, representing the ecological toll of always producing newer and ‘better’ products and selling them. We cannot have infinite growth on a finite planet.

It may seem that we are discarding many of your original ideas. However, the rigorous research which you promoted and engaged in remains central to our work. One aspect of rigorous research, which you supported, is the need to adopt the methods which are proven to work the best, which is why we are making these shifts. We continue to be engaged in research which aims to find the most ecologically efficient methods of production and living and better them. We use our new knowledge to refine the technologies and ideas you developed.

While rigorous scientific research remains central to our mission, we have expanded research to include listening to the perspectives of other peoples and sociological research, since researchers often take things for granted which limits their options. Like we said, one with a limited viewpoint might not imagine or think that the technologies and methods of indigenous peoples might, in some ways, be more efficient than our current technologies. With a greater breadth of people informing our beliefs, we can research more options. Research gives accurate answers, but one must read more than just science to determine which questions to ask.

Your teachings and model of a life dedicated to the betterment of humanity continue to inspire us. Your contribution to ecological design and our common home will never be forgotten. We are writing to you in grim times for the Earth, yes, but we will not stop as long as we have the ability to help people, no matter how small the odds of changing the course of our destructive systems often seem. Your commitment to rigorous research continues to be central to our methods, and we thank you for the ways in which you supported it throughout your life. Although our path has shifted, we will never give up our central mission of betterment for all humanity.

Sincerely,

Ecological Designers of Earth

Notes

- Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” accessed March 14, 2021, https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions

- Laura Parker, “The World’s Plastic Pollution Crisis Explained,” National Geographic, June 7, 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/plastic-pollution

- “Buckminster Fuller, ‘Spaceship Earth’”, InfiniteMIT, filmed 1979, https://infinite.mit.edu/video/buckminster-fuller-spaceship-earth%E2%80%9D-3141979

- “We Are Indigenous: Sustainability Inherent to Indigenous Political Ecology,” UN Academic Impact, September 2nd, 2020, https://academicimpact.un.org/content/we-are-indigenous-sustainability-inherent-indigenous-political-ecology

- Gleb Raygorodetsky, “Indigenous Peoples Defend Earth’s Biodiversity-But They’re In Danger,” National Geographic, November 16, 2018, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/can-indigenous-land-stewardship-protect-biodiversity-

- Niall McCarthy, “Report: The U.S. Military Emits More CO2 Than Many Industrialized Nations [Infographic],” Forbes, June 13, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2019/06/13/report-the-u-s-military-emits-more-co2-than-many-industrialized-nations-infographic/?sh=582be6e44372

- Peter Anker, “Buckminster Fuller as Captain of Spaceship Earth,” Minerva (London) 45, no. 4 (2007): 423. http://www.jstor.com/stable/41821426

- “Buckminster Fuller, ‘Spaceship Earth’”, InfiniteMIT, filmed 1979, https://infinite.mit.edu/video/buckminster-fuller-spaceship-earth%E2%80%9D-3141979

- Peter Anker, “Buckminster Fuller as Captain of Spaceship Earth,” Minerva (London) 45, no. 4 (2007): 432. http://www.jstor.com/stable/41821426

- “Mud Frontiers”, Rael San Fratello, Copyright 2021, https://www.rael-sanfratello.com/made/mud-frontiers

- We Don’t Have Time, “IKEA Starts Using Biodegradable Mushroom-Based Packaging for Its Products,” Medium, April 11, 2018, https://medium.com/wedonthavetime/ikea-starts-using-biodegradable-mushroom-based-packaging-for-its-products-42d079f98bb1

- Peter Killy-Detwiler, “Solar Technology Will Just Keep Getting Better: Here’s Why,” Forbes, September 26, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/peterdetwiler/2019/09/26/solar-technology-will-just-keep-getting-better-heres-why/?sh=7123f7547c6b

- Lucy Wang, “8 Homes That Generate More Energy Than They Consume,” Inhabitat, April 7, 2017, https://inhabitat.com/8-homes-that-generate-more-energy-than-they-consume/

- Peter Anker, “Buckminster Fuller as Captain of Spaceship Earth,” Minerva (London) 45, no. 4 (2007): 433. http://www.jstor.com/stable/41821426

- Murray Bookchin, “Utopia, Not Futurism: Why Doing The Impossible Is The Most Rational Thing We Can Do,” Uneven Earth, recorded 1978, http://unevenearth.org/2019/10/bookchin_doing_the_impossible/#easy-footnote-5-3428

- Murray Bookchin, “Toward a Communalist Approach,” The Anarchist Library, 2006, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/murray-bookchin-toward-a-communalist-approach

- Luke, Timothy W, “Ephemeralization as Environmentalism: Rereading R. Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth.” Organization & Environment 23, no. 3 (2010): 360. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1086026610381582

- “Via Binarii,”, Unfold, June 13, 2019, http://unfold.be/pages/via-binarii.html

- “Buckminster Fuller, ‘Spaceship Earth’”, InfiniteMIT, filmed 1979, https://infinite.mit.edu/video/buckminster-fuller-spaceship-earth%E2%80%9D-3141979

- “Buckminster Fuller, ‘Spaceship Earth’”, InfiniteMIT, filmed 1979, https://infinite.mit.edu/video/buckminster-fuller-spaceship-earth%E2%80%9D-3141979

- “R. Buckminster Fuller and Systems Theory,” University of Missouri-St. Louis, accessed March 14, 2021, http://umsl.edu/~sauterv/analysis/Fall2013Papers/Purcell/bucky.html#3i

Media Attributions

- Installing Solar Panels © Oregon Department of Transportation is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Dymaxion House © Sasha Pohflepp is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Artisam’s Asylum © Erik Borälv is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- What I’m Waiting For © Miguel Symonds Orr is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Within This Future © Miguel Symonds Orr is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Peter Anker, “Buckminster Fuller as Captain of Spaceship Earth,” Minerva (London) 45, no. 4 (2007): 433. http://www.jstor.com/stable/41821426 ↵

- Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” accessed March 14, 2021, https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions ↵

- Laura Parker, “The World’s Plastic Pollution Crisis Explained,” National Geographic, June 7, 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/plastic-pollution ↵

- Buckminster Fuller, "Spaceship Earth”, InfiniteMIT, filmed 1979, https://infinite.mit.edu/video/buckminster-fuller-spaceship-earth%E2%80%9D-3141979 ↵

- “We Are Indigenous: Sustainability Inherent to Indigenous Political Ecology,” UN Academic Impact, September 2nd, 2020, https://academicimpact.un.org/content/we-are-indigenous-sustainability-inherent-indigenous-political-ecology ↵

- Gleb Raygorodetsky, “Indigenous Peoples Defend Earth’s Biodiversity-But They’re In Danger,” National Geographic, November 16, 2018, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/can-indigenous-land-stewardship-protect-biodiversity- ↵

- Niall McCarthy, “Report: The U.S. Military Emits More CO2 Than Many Industrialized Nations [Infographic],” Forbes, June 13, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2019/06/13/report-the-u-s-military-emits-more-co2-than-many-industrialized-nations-infographic/?sh=582be6e44372 ↵

- Peter Anker, “Buckminster Fuller as Captain of Spaceship Earth,” 423. ↵

- “Buckminster Fuller, ‘Spaceship Earth’”, InfiniteMIT, filmed 1979, https://infinite.mit.edu/video/buckminster-fuller-spaceship-earth%E2%80%9D-3141979 ↵

- Peter Anker, “Buckminster Fuller as Captain of Spaceship Earth,” 432. ↵

- “Mud Frontiers”, Rael San Fratello, Copyright 2021, https://www.rael-sanfratello.com/made/mud-frontiers ↵

- We Don’t Have Time, “IKEA Starts Using Biodegradable Mushroom-Based Packaging for Its Products,” Medium, April 11, 2018, https://medium.com/wedonthavetime/ikea-starts-using-biodegradable-mushroom-based-packaging-for-its-products-42d079f98bb1 ↵

- Peter Killy-Detwiler, “Solar Technology Will Just Keep Getting Better: Here’s Why,” Forbes, September 26, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/peterdetwiler/2019/09/26/solar-technology-will-just-keep-getting-better-heres-why/?sh=7123f7547c6b ↵

- Lucy Wang, “8 Homes That Generate More Energy Than They Consume,” Inhabitat, April 7, 2017, https://inhabitat.com/8-homes-that-generate-more-energy-than-they-consume/ ↵

- Peter Anker, “Buckminster Fuller as Captain of Spaceship Earth,” 433 ↵

- Murray Bookchin, "Utopia, Not Futurism: Why Doing The Impossible Is The Most Rational Thing We Can Do," Uneven Earth, recorded 1978, http://unevenearth.org/2019/10/bookchin_doing_the_impossible/#easy-footnote-5-3428 ↵

- Murray Bookchin, "Toward a Communalist Approach," The Anarchist Library, 2006, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/murray-bookchin-toward-a-communalist-approach ↵

- Luke, Timothy W, “Ephemeralization as Environmentalism: Rereading R. Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth.” Organization & Environment 23, no. 3 (2010): 360. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1086026610381582 ↵

- “Via Binarii,”, Unfold, June 13, 2019, http://unfold.be/pages/via-binarii.html ↵

- Buckminster Fuller, “Spaceship Earth”. ↵

- Buckminster Fuller, “Spaceship Earth”. ↵

- “R. Buckminster Fuller and Systems Theory,” University of Missouri-St. Louis, accessed March 14, 2021, http://umsl.edu/~sauterv/analysis/Fall2013Papers/Purcell/bucky.html#3i ↵