19 Women’s & Gender Studies at Community Colleges: Breakthroughs and Challenges

By Shereen Siddiqui, Santiago Canyon College

Feminist pedagogy arose with the emergence of Women’s Studies programs and the realization by feminist teachers that American education—both in course content and pedagogy—did not address the needs, concerns, experiences, and perspectives of women and other marginalized groups (Siddiqui 2015, 16).[1] Feminist teachers “recognized that drawing connections between lived experiences and course materials, while actively engaging students in the learning process, not only aids students in learning the material, but is also crucial for the creation of an environment in which students view themselves as capable of applying their knowledge to social problems” (Siddiqui 2015; Maher and Tetreault 1994) and of transforming their own lives and the world. Women’s and Gender Studies (WGS) programs continue to make central the experiences of the oppressed, and our faculty routinely bear witness to the “lightbulb moment” when our students connect the personal and political. This connection is strikingly evident in our nation’s community colleges.[2]

Community colleges in the US enroll over 40 percent of all undergraduates, catering to historically underserved, first-generation, low-income, and minority students (Carminati and Rellihan 2019, xx-xxi). Emphasizing the development of a sociological imagination, giving voice to marginalized groups, and encouraging the connection between theory and action, WGS programs at community colleges are “critical sites of learning” for underprivileged students, and these spaces at community college are natural incubators for the field of Women’s and Gender Studies (Carminati and Rellihan 2019). Despite their importance, WGS programs at community colleges are underfunded and rarely researched. This essay focuses on the ways in which WGS faculty at community colleges create “critical sites of resistance and spaces of belonging for marginalized students” (Carminati and Rellihan 2019), and the challenges and threats we face in the process.

I write as a “representative” for Women’s and Gender Studies at community colleges, but most of my twenty-five year career in higher education has been at large, public, four-year universities—my first career was in student affairs, my second as a Women’s Studies instructor at a four-year university. It was not until the semester before I defended my dissertation when a friend from my PhD program had to back out of an adjunct teaching gig at a nearby community college, because she landed a coveted full-time position at a four-year, and asked if she could give them my name to replace her. I had never taught at a community college. I said yes. I figured I was about to enter the job market myself and could use another line on my CV. I didn’t realize that this decision would change my life and the trajectory of my career.

Until I taught at a community college, I held some negative stereotypes about the students and teachers at these institutions. I thought most of the students were there because they couldn’t get into a four-year school, or they had no direction. It was an extension of high school. Ugly concrete buildings and parking lots, far from the old, ivy-covered brick buildings of my college alma mater. And I thought the faculty were there because it was the only job they could land, a last resort. In both cases, less than, not as good as. I thought I was better than. I am embarrassed to admit all of this, but it is important to do so, because I have learned that these are common stereotypes that people have about community colleges. Needless to say, these stereotypes are damaging and problematic for many reasons. As Sara Hosey bluntly asks, “What does it say about our democracy if ‘democracy’s colleges’ are widely imagined to be shitholes” (2019, 76)?

It did not take me long to realize how wrong I had been. I work with teaching rock stars. I often marvel that they hired me to work with them. And my students are some of the smartest and most driven I have ever encountered. They do not take their education for granted. Their families have made sacrifices for them to be here and have pinned all their hopes on them. I see myself in them. Not only was I the first woman in my family to attend college, but I was the first to know how to read and write. For most of my students, too, education is their ticket to freedom. But hierarchies of race and class, which are “reflected and perpetuated by the bifurcation of higher education,” (Carminati and Rellihan 2019, xxi) make it difficult for them to overcome the barriers in front of them.

However, a lifetime of marginality has made them natural theorists. I do not need to spend an entire semester helping them develop a sociological imagination. I do not have to hand them an intersectional lens when they walk into my classroom. They already have it. We are just giving them the language and the affirmation that they are not alone. The WGS classroom then becomes a safe and liberatory space where they may, as bell hooks says, “connect the will to know with the will to become” (1994, 18-19).

Much of what I share in this essay is an echo of Genevieve Carminati and Heather Rellihan’s groundbreaking work in Theory and Praxis: Women’s and Gender Studies at Community Colleges (2019). It is the first book about WGS at community colleges, which suggests just how under-researched we are. So, who are we? In short, community college students are underserved, first-generation, low-income, and minoritized:

- 41% of all US undergraduates (Carminati and Rellihan 2019)

- 55% of dependent students with family incomes below $30,000 (Community College Research Center)

- 57% of all Native American undergraduates (American Association of Community Colleges 2020)

- 52% of all Latinx undergraduates (American Association of Community Colleges 2020)

- 42% of all Black/African American undergraduates (American Association of Community Colleges 2020)

- 36% have parents with no college experience (compared to 29% average for all undergrad institutions) (Carminati and Rellihan 2019; Ma and Baum 2016)

- 20% have a disability (compared to 17% at 4-year) (Carminati and Rellihan 2019; American Association of Community Colleges 2018)

- Community colleges are also predominantly female spaces: 57% community college students are female, as is 57% management, 75% business and financial operations, 81% office and administration support, 53% instructional staff, and 65% student affairs and other education services positions (Carminati and Rellihan 2019; American Association of Community Colleges 2020)

Faculty make-up suggests slightly less precarity than PhD- and MA-awarding universities: community colleges are 51% of full-time female professors (compared to 31% at doctorate award-granting universities and 42% at bachelor’s and master’s degree-granting colleges and universities)[3] (Carminati and Rellihan 2019; West and Curtis 2006).

WGS at Community Colleges

There are about 100 WGS community college programs throughout the US, meaning about 10 percent of all community colleges have some sort of WGS presence. This includes everything from colleges like mine that offer a degree in WGS, with full-time WGS faculty, to those that just offer a course or two (Rellihan and Stoehr 2019). Despite the fertile ground community colleges provide WGS, we face many challenges as well. I now turn to those.

Tension/hypocrisy in the field: As we know, there is a lot of talk in Women’s Studies about equity and trying to help people who are oppressed, yet the field has provided little support to or respect for WGS at community colleges. As an example, a community college instructor colleague of mine was invited to speak to Women’s Studies grad students on a panel about non-academic job opportunities for WGS graduates (Rellihan 2019, xvi). Even at the National Women’s Studies Association (NWSA) Conference in November 2019, faculty members in attendance at the Community College Caucus meeting expressed frustration at how we are marginalized within NWSA and made to feel that we are not teaching at “real” colleges. In my estimation, the institutionalization of the discipline has taken us further from our activist roots and has further marginalized community colleges, women’s centers, and activists.

Emotional labor: Because we disproportionately serve disadvantaged groups, community college faculty, especially women, are doing an incredible amount of emotional labor, on top of our teaching loads[4] and our other obligations to the college. On my campus, for example, our total enrollment is about 16,000, and we have ONE psychologist. Most of our students do not have access to mental health services. WGS faculty everywhere share the experience of students coming to us with their traumas, but because community college students often come from the most marginalized groups, our WGS faculty offices become revolving doors of tragedy. I have had students who are homeless, students who are food insecure, a student who could not come to class because his meth-addicted mother disappeared for a week and when she came back, she had burns all over her body, and he had to rub medicine on her at certain times and also take his little brother to school. There is something every day, and I have to stop what I am doing and figure out resources, where to send them, make phone calls, find someone who can help. And I continue to worry about them after they leave my office. We know that WGS faculty are expected to do emotional labor at all types of institutions (see Bauer 2002; Shayne 2017). At community colleges, however, there are fewer faculty to take on the labor, the students have far fewer resources at home, and our campuses are unable to prioritize, or in some cases even offer, mental health services, due to lack of funding (Anderson 2019).

Guided Pathways: Guided Pathways are credential-based programs that community colleges are implementing to increase graduation rates. These programs assume that the current “cafeteria model” where students pick and choose classes is flawed. Instead, students select a major related to a career and are put on a pathway to complete their degree (Bailey, Jaggars, and Jenkins 2015). I do not think we have enough data from other schools yet to say if it actually “works” but from a WGS perspective, I do have some concerns. If our WGS classes are not deemed relevant to a particular career, we are not going to be on that student’s pathway, and they will not be able to take our classes. The larger issue is the message we are sending to economically disadvantaged students. Systems are being constructed that infantilize marginalized students, eliminate choice, and preclude poor students from having access to the same educational opportunities as students at four-year universities.

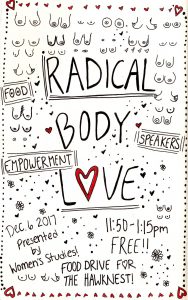

Academic Freedom: This is a flyer that student Sophia Moore, from one of my Intro classes, created for an event we held on campus. A male student at the College saw the flyer, went to administration to find our Title IX Officer, found our VP instead, and told her the flyers made him feel “harassed and violated.” I was ordered to take them all down. No dialogue; no discussion. The fear of litigation is impacting our ability to do our jobs.

Precariousness of WGS programs and courses: All WGS programs are vulnerable to budget cuts—this is no secret, and it is likely to get much worse with the COVID-19 budget crises in which campuses everywhere are finding themselves. (See WGSC, 2020). Although we have seen some positive steps at community colleges, such as the addition of two full-time WGS positions at my college, as well as the creation of degrees and certificates at other community colleges, there is the ever-present looming threat that our programs will be cut or lose funding. We have seen this most recently at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, New York, which last year defunded WGS and took away their office space (Washburn 2019).

Call to Action

Fellow GWSS faculty, there are many things you can do to upset this pattern of community college subordination. First, please check your own biases. Invite community college faculty to research and write with you. If you participate in a journal, invite folks at community colleges into the conversation. Accept transfer credits from community colleges. NWSA and other feminist organizations need to reach out to community colleges and invite us to participate in conferences and events, especially by offering scholarships. Encourage your graduate students to teach at community colleges. Offer internship credit for teaching assistantships at community colleges. As Sarah Hosey argues,

It must be part of the larger feminist agenda to more fully support the work that goes on in community colleges. Ignoring community college students, faculty, and work reflects a larger surrender to a neoliberal postfeminist severing of the personal and the political. That is, if you don’t see and struggle with and for students in community colleges, you become one of the voices telling these individuals, you are not real students, you are on your own, your voices, stories, and needs are not important (2019, 87).

Teaching WGS at a community college is the most challenging and rewarding job I have ever had. Despite all the challenges, I truly love what I do and feel that it matters. I have never felt more that I am doing the work of Women’s Studies than I have at the community college. My classrooms are the most radical places I have ever worked. It is my hope that this essay will cultivate solidarity between community college and non-community college faculty and students.

Works cited:

American Association of Community Colleges. “Fast Facts 2020.” https://www.aacc.nche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/AACC_Fast_Facts_2020_Final.pdf. [Accessed: July 9, 2020.]

American Association of Community Colleges. 2016. “Female Campus Administrators.” DataPoints, 4(5). https://www.aacc.nche.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2017/09/DP_FemaleAdmin.pdf. [Accessed: July 9, 2020.]

American Association of Community Colleges. 2018. “Students with Disabilities.” DataPoints, 6(13). https://www.aacc.nche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DataPoints_V6N13.pdf. [Accessed: July 9, 2020.]

Anderson, Greta. 2019. “Defunding Student Mental Health.” In Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/10/18/mental-health-low-priority-community-colleges. [Accessed: July 2, 2020.]

Bailey, Thomas R., Shanna Smith Jaggars, and Davis Jenkins. 2015. Redesigning America’s Community Colleges – A Clearer Path to Student Success Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bauer, Dale M. 2002. “Academic Housework: Women’s Studies and Second Shifting.” In Women’s Studies on its Own: A Next Wave Reader in Institutional Change, ed., Robyn Wiegman, 245-257. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Carminati, Genevieve and Heather Rellihan, eds. 2019. Theory & Praxis: Women’s and Gender Studies at Community Colleges. Arlington, VA.: Gival Press

Community College Research Center. “Community College FAQs.” https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/Community-College-FAQs.html. [Accessed: July 9, 2020.]

hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hosey, Sara, 2019. “The Community College as an Enabling Institution: Women’s Studies Programs Resisting the Neoliberal Severing of the Personal and Political.” In Theory and Praxis: Women’s and Gender Studies at Community Colleges, eds., Genevieve Carminati and Heather Rellihan, 75-91. Arlington, VA.: Gival Press.

Ma, Jennifer and Sandy Baum. 2016. “Trends in Community Colleges: Enrollment, Prices, Student Debt, and Completion.” College Board Research. trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/trends-in-community-colleges-research-brief.pdf. [Accessed: July 9, 2020.]

Maher, Frances A. and Mary Kay Thompson Tetreault. 1994. The Feminist Classroom. New York, NY: BasicBooks.

Rellihan, Heather. 2019. “Personal Narratives in WGS at Community Colleges: Challenges.” In Theory and Praxis: Women’s and Gender Studies at Community Colleges, eds., Genevieve Carminati and Heather Rellihan, xvi-xx. Arlington, VA.: Gival Press.

Rellihan, Heather, and Alissa Stoehr. “The Status of Women’s and Gender Studies at Community Colleges.” In Theory and Praxis: Women’s and Gender Studies at Community Colleges, eds., Genevieve Carminati and Heather Rellihan, 1-31. Arlington, VA.: Gival Press.

Shayne, Julie. 2017, September 15. “Recognizing Emotional Labor in Academe.” In Conditionally Accepted. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2017/09/15/importance-recognizing-faculty-their-emotional-support-students-essay. [Accessed May 19, 2020.]

Siddiqui, Shereen. 2015. “Teaching to Transform: Toward an Action-Oriented Feminist Pedagogy in Women’s Studies.” (Doctoral dissertation). Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL.

UW System Women’s and Gender Studies Consortium (WGSC). 2020, June 11. “COVID-19, Disaster Capitalism and the Crisis in Women’s and Gender Studies.” In Ms. Magazine, online. https://msmagazine.com/2020/06/11/covid-19-disaster-capitalism-and-the-crisis-in-womens-and-gender-studies/ [Accessed: 7/9/2020]

Washburn, Red. 2019. “Endangered Studies, Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Community College in #MeToo Times: A Case Study of Kingsborough Community College as a Microcosm of Neoliberal Education.” In Theory and Praxis: Women’s and Gender Studies at Community Colleges, eds., Genevieve Carminati and Heather Rellihan, 213-220. Arlington, VA.: Gival Press.

West, Martha, and John W. Curtis. 2006. AAUP Faculty Gender Equity Indicators, 2006. American Association of University Professors. https://www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/63396944-44BE-4ABA-9815-5792D93856F1/0/AAUPGenderEquityIndicators2006.pdf. [Accessed: July 9, 2020.]

- I am indebted to Heather Rellihan of Anne Arundel Community College for the conversation that sparked this essay and for her willingness to read a draft of it. ↵

- This is a slightly modified version of an invited talk I gave at the Sociologists for Women in Society winter meeting, January 2020. I was part of the plenary session titled: “50 Years of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies: Looking Backwards, Looking Forward.” San Diego, CA. ↵

- I don’t have numbers for women of color faculty, but based on my own experiences and those of my colleagues at other institutions, I suspect there are more of us at community colleges. ↵

- As of this writing, I taught 14 classes in AY 2019-20, including summer. I am contractually obligated to teach 10. ↵