56 Regulation: Protecting People from the Market

Learning Objectives

- Compare the public interest and public choice theories of regulation.

- Discuss the costs and benefits of consumer protection laws.

- Discuss the pros and cons of the trend toward deregulation over the last quarter century.

Antitrust policies are primarily concerned with limiting the accumulation and use of market power. Government regulation is used to control the choices of private firms or individuals. Regulation may constrain the freedom of firms to enter or exit markets, to establish prices, to determine product design and safety, and to make other business decisions. It may also limit the choices made by individuals.

In general terms, there are two types of regulatory agencies. One group attempts to protect consumers by limiting the possible abuse of market power by firms. The other attempts to influence business decisions that affect consumer and worker safety. Regulation is carried out by more than 50 federal agencies that interpret the applicable laws and apply them in the specific situations they find in real-world markets. Table 9.4 “Selected Federal Regulatory Agencies and Their Missions” lists some of the major federal regulatory agencies, many of which are duplicated at the state level.

Table 9.4 Selected Federal Regulatory Agencies and Their Missions

| Financial Markets | |

| Federal Reserve Board | Regulates banks and other financial institutions |

| Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation | Regulates and insures banks and other financial institutions |

| Securities and Exchange Commission | Regulates and requires full disclosure in the securities (stock) markets |

| Commodity Futures Trading Commission | Regulates trading in futures markets |

| Product Markets | |

| Department of Justice, Antitrust Division | Enforces antitrust laws |

| Federal Communications Commission | Regulates broadcasting and telephone industries |

| Federal Trade Commission | Focuses efforts on consumer protection, false advertising, and unfair trade practices |

| Federal Maritime Commission | Regulates international shipping |

| Surface Transportation Board | Regulates railroads, trucking, and noncontiguous domestic water transportation |

| Federal Energy Regulatory Commission | Regulates pipelines |

| Health and Safety | |

| Occupational Health and Safety Administration | Regulates health and safety in the workplace |

| National Highway Traffic Safety Administration | Regulates and sets standards for motor vehicles |

| Federal Aviation Administration | Regulates air and traffic aviation safety |

| Food and Drug Administration | Regulates food and drug producers; emphasis on purity, labeling, and product safety |

| Consumer Product Safety Commission | Regulates product design and labeling to reduce risk of consumer injury |

| Energy and the Environment | |

| Environmental Protection Agency | Sets standards for air, water, toxic waste, and noise pollution |

| Department of Energy | Sets national energy policy |

| Nuclear Regulatory Commission | Regulates nuclear power plants |

| Corps of Engineers | Sets policies on construction near rivers, harbors, and waterways |

| Labor Markets | |

| Equal Employment Opportunity Commission | Enforces antidiscrimination laws in the workplace |

| National Labor Relations Board | Enforces rules and regulations governing contract bargaining and labor relations between companies and unions |

Theories of Regulation

Competing explanations for why there is so much regulation range from theories that suggest regulation protects the public interest to those that argue regulation protects the producers or serves the interests of the regulators. The distinction corresponds to our discussion in the last chapter of the public interest versus the public choice understanding of government policy in general.

The Public Interest Theory of Regulation

The public interest theory of regulation holds that regulators seek to find market solutions that are economically efficient. It argues that the market power of firms in imperfectly competitive markets must be controlled. In the case of natural monopolies (discussed in an earlier chapter), regulation is viewed as necessary to lower prices and increase output. In the case of oligopolistic industries, regulation is often advocated to prevent cutthroat competition.

The public interest theory of regulation also holds that firms may have to be regulated in order to guarantee the availability of certain goods and services—such as electricity, medical facilities, and telephone service—that otherwise would not be profitable enough to induce unregulated firms to provide them in a given community. Firms providing such goods and services are often granted licenses and franchises that prevent competition. The regulatory authority allows the firm to set prices above average cost in the protected market in order to cover losses in the target community. In this way, the firms are allowed to earn, indeed are guaranteed, a reasonable rate of return overall.

Proponents of the public interest theory also justify regulation of firms by pointing to externalities, such as pollution, that are not taken into consideration when unregulated firms make their decisions. As we have seen, in the absence of property rights that force the firms to consider all of the costs and benefits of their decisions, the market may fail to allocate resources efficiently.

The Public Choice Theory of Regulation

The public interest theory of regulation assumes that regulations serve the interests of consumers by restricting the harmful actions of business firms. That assumption, however, is now widely challenged by advocates of the public choice theory of regulation, which rests on the premise that all individuals, including public servants, are driven by self-interest. They prefer the capture theory of regulation, which holds that government regulations often end up serving the regulated firms rather than their customers.

Competing firms always have an incentive to collude or operate as a cartel. The public is protected from such collusion by a pervasive incentive for firms to cheat. Capture theory asserts that firms seek licensing and other regulatory provisions to prevent other firms from entering the market. Firms seek price regulation to prevent price competition. In this view, the regulators take over the role of policing cartel pricing schemes; individual firms in a cartel would be incapable of doing so themselves.

Because it is practically impossible for the regulatory authorities to have as much information as the firms they are regulating, and because these authorities often rely on information provided by those firms, the firms find ways to get the regulators to enforce regulations that protect profits. The regulators get “captured” by the very firms they are supposed to be regulating.

In addition to its use of the capture theory, the public choice theory of regulation argues that employees of regulatory agencies are not an exception to the rule that people are driven by self-interest. They maximize their own satisfaction, not the public interest. This insight suggests that regulatory agencies seek to expand their bureaucratic structure in order to serve the interests of the bureaucrats. As the people in control of providing government protection from the rigors of the market, bureaucrats respond favorably to lobbyists and special interests.

Public choice theory views the regulatory process as one in which various groups jockey to pursue their respective interests. Firms might exploit regulation to limit competition. Consumers might seek lower prices or changes in products. Regulators themselves might pursue their own interests in expanding their prestige or incomes. The abstract goal of economic efficiency is unlikely to serve the interest of any one group; public choice theory does not predict that efficiency will be a goal of the regulatory process. Regulation might improve on inefficient outcomes, but it might not.

Consumer Protection

Every day we come into contact with regulations designed to protect consumers from unsafe products, unscrupulous sellers, or our own carelessness. Seat belts are mandated in cars and airplanes; drivers must provide proof of liability insurance; deceptive advertising is illegal; firms cannot run “going out of business” sales forever; electrical and plumbing systems in new construction must be inspected and approved; packaged and prepared foods must carry certain information on their labels; cigarette packages must warn users of the dangers involved in smoking; gasoline stations must prevent gas spillage; used-car odometers must be certified as accurate. The list of regulations is seemingly endless.

There are often very good reasons behind consumer protection regulation, and many economists accept such regulation as a legitimate role and function of government agencies. But there are costs as well as benefits to consumer protection.

The Benefits of Consumer Protection

Consumer protection laws are generally based on one of two conceptual arguments. The first holds that consumers do not always know what is best for them. This is the view underlying government efforts to encourage the use of merit goods and discourage the use of demerit goods. The second suggests that consumers simply do not have sufficient information to make appropriate choices.

Laws prohibiting the use of certain products are generally based on the presumption that not all consumers make appropriate choices. Drugs such as cocaine and heroin are illegal for this reason. Children are barred from using products such as cigarettes and alcohol on grounds they are incapable of making choices in their own best interest.

Other regulations presume that consumers are rational but may not have adequate information to make choices. Rather than expect consumers to determine whether a particular prescription drug is safe and effective, for example, federal regulations require the Food and Drug Administration to make that determination for them.

The benefit of consumer protection occurs when consumers are prevented from making choices they would regret if they had more information. A consumer who purchases a drug that proves ineffective or possibly even dangerous will presumably stop using it. By preventing the purchase in the first place, the government may save the consumer the cost of learning that lesson.

One problem in assessing the benefits of consumer protection is that the laws themselves may induce behavioral changes that work for or against the intent of the legislation. For example, requirements for childproof medicine containers appear to have made people more careless with medicines. Requirements that mattresses be flame-resistant may make people more careless about smoking in bed. In some cases, then, the behavioral changes attributed to consumer protection laws may actually worsen the problem the laws seek to correct.

An early study on the impact of seat belts on driving behavior indicated that drivers drove more recklessly when using seat belts, presumably because the seat belts made them feel more secure (Peltzman, S., 1975). A recent study, however, found that this was not the case and suggests that use of seat belts may make drivers more safety-conscious (Cohen, A., and Liran Einan, 2003).

In any event, these “unintended” behavioral changes can certainly affect the results achieved by these laws.

The Cost of Consumer Protection

Regulation aimed at protecting consumers can benefit them, but it can also impose costs. It adds to the cost of producing goods and services and thus boosts prices. It also restricts the freedom of choice of individuals, some of whom are willing to take more risks than others.

Those who demand, and are willing to pay the price for, high-quality, safe, warranted products can do so. But some argue that people who demand and prefer to pay (presumably) lower prices for lower-quality products that may have risks associated with their use should also be allowed to exercise this preference. By increasing the costs of goods, consumer protection laws may adversely affect the poor, who are forced to purchase higher-quality products; the rich would presumably buy higher-quality products in the first place.

To assess whether a particular piece of consumer protection is desirable requires a careful look at how it stacks up against the marginal decision rule. The approach of economists is to attempt to determine how the costs of a particular regulation compare to its benefits.

Economists W. Mark Crain and Thomas D. Hopkins estimated the cost of consumer protection regulation in 2001 and found that the total cost was $843 billion, or $7,700 per household in the United States (Crain, W. M., and Thomas D. Hopkins, 2001).

Deregulating the Economy

Concern that regulation might sometimes fail to serve the public interest prompted a push to deregulate some industries, beginning in the late 1970s. In 1978, for example, Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act, which removed many of the regulations that had prevented competition in the airline industry. Safety regulations were not affected. The results of deregulation included a substantial reduction in airfares, the merger and consolidation of airlines, and the emergence of frequent flier plans and other marketing schemes designed to increase passenger miles. Not all the consequences of deregulation were applauded, however. Many airlines, unused to the demands of a competitive, unprotected, and unregulated environment, went bankrupt or were taken over by other airlines. Large airlines abandoned service to small and midsized cities, and although most of these routes were picked up by smaller regional airlines, some consumers complained about inadequate service. Nevertheless, the more competitive airline system today is probably an improvement over the highly regulated industry that existed in the 1970s. It is certainly cheaper. Table 16.3 “Improvement in Consumer Welfare from Deregulation” suggests that the improvements in consumer welfare from deregulation through the 1990s have been quite substantial across a broad spectrum of industries that have been deregulated.

Table 9.4 Improvement in Consumer Welfare from Deregulation

| Industry | Improvements |

|---|---|

| Airlines | Average fares are roughly 33% lower in real terms since deregulation, and service frequently has improved significantly. |

| Less-than-truckload trucking | Average rates per vehicle mile have declined at least 35% in real terms since deregulation, and service times have improved significantly. |

| Truckload trucking | Average rates per vehicle mile have declined by at least 75% in real terms since deregulation, and service times have improved significantly. |

| Railroads | Average rates per ton-mile have declined more than 50% in real terms since deregulation, and average transit time has fallen more than 20%. |

| Banking | Consumers have benefited from higher interest rates on deposits, from better opportunities to manage risk, and from more banking offices and automated teller machines. |

| Natural gas | Average prices for residential customers have declined at least 30% in real terms since deregulation, and average prices for commercial and industrial customers have declined more than 30%. In addition, service has been more reliable as shortages have been almost completely eliminated. |

Economist Clifford Winston found substantial benefits from deregulation in the five industries he studied—airlines, trucking, railroads, banking, and natural gas.

Source: Clifford Winston, “U.S. Industry Adjustment to Economic Deregulation,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 12(3) (Summer 1998): 89–110.

But there are forces working in the opposite direction as well. Many businesses continue to turn to the government for protection from competition. Public choice theory suggests that more, not less, regulation is often demanded by firms threatened with competition at home and abroad. More and more people seem to demand environmental protection, including clear air, clean water, and regulation of hazardous waste and toxic waste. Indeed, as incomes rise over time, there is evidence that the demand for safety rises. This market phenomenon began before the birth of regulatory agencies and can be seen in the decline in unintentional injury deaths over the course of the last hundred years (Viscusi, W. K., 2002). And there is little reason to expect less demand for regulations in the areas of civil rights, handicapped rights, gay rights, medical care, and elderly care.

The basic test of rationality—that marginal benefits exceed marginal costs—should guide the formulation of regulations. While economists often disagree about which, if any, consumer protection regulations are warranted, they do tend to agree that market incentives ought to be used when appropriate and that the most cost-effective policies should be pursued.

Key Takeaways

- Federal, state, and local governments regulate the activities of firms and consumers.

- The public interest theory of regulation asserts that regulatory efforts act to move markets closer to their efficient solutions.

- The public choice theory of regulation argues that regulatory efforts serve private interests, not the public interest.

- Consumer protection efforts may sometimes be useful, but they tend to produce behavioral responses that often negate the effort at protection.

- Deregulation efforts through the 1990s generally produced large gains in consumer welfare, though demand for more regulation is rising in certain areas, especially finance.

Try It!

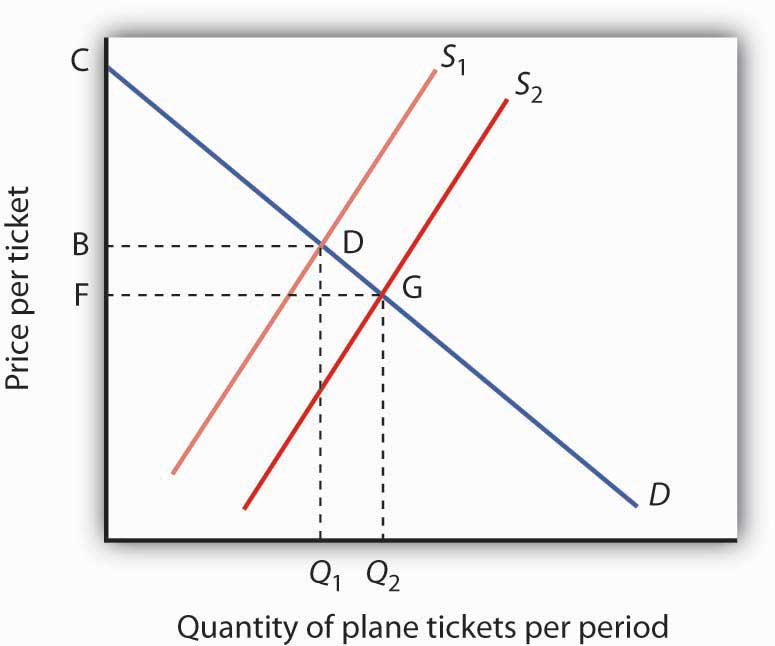

The deregulation of the airline industry has generally led to lower fares and increased quantities produced. Use the model of demand and supply to show this change. What has happened to consumer surplus in the market? (Hint: You may want to refer back to the earlier discussion of consumer surplus.)

Case in Point: Do Consumer Protection Laws Protect Consumers?

Economist W. Kip Viscusi of the Harvard Law School has long advocated economic approaches to health and safety regulations. Economic approaches recognize 1) behavioral responses to technological regulations; 2) performance-oriented standards as opposed to command-and-control regulations; and 3) the opportunity cost of regulations. Below are some examples of how these economic approaches would improve health and safety policy.

Behavioral responses: Consider the requirement, imposed in 1972, that aspirin containers have childproof caps. That technological change seemed straightforward enough. But, according to Mr. Viscusi, the result has not been what regulators expected. Mr. Viscusi points out that childproof caps are more difficult to open. They thus increase the cost of closing the containers properly. An increase in the cost of any activity reduces the quantity demanded. So, childproof caps result in fewer properly closed aspirin containers.

Mr. Viscusi calls the response to childproof caps a “lulling effect.” Parents apparently think of containers as safer and are, as a result, less careful with them. Aspirin containers, as well as other drugs with childproof caps, tend to be left open. Mr. Viscusi says that the tragic result is a dramatic increase in the number of children poisoned each year. Hence, he urges government regulators to take behavioral responses into account when promulgating technological solutions. He also advocates well-articulated hazard warnings that give consumers information on which to make their own choices.

Performance-oriented standards: Once a health and safety problem has been identified, the economic approach would be to allow individuals or firms discretion in how to address the problem as opposed to mandating a precise solution. Flexibility allows a standard to be met in a less costly way and can have greater impact than command-and-control approaches. Mr. Viscusi cites empirical evidence that worker fatality rates would be about one-third higher were it not for the financial incentives firms derive from creating a safer workplace and thereby reducing the workers’ compensation premiums they pay. In contrast, empirical estimates of the impact of OSHA regulations, most of which are of the command-and-control type, range from nil to a five to six percent reduction in worker accidents that involve days lost from work.

Opportunity cost of regulations: Mr. Viscusi has estimated the cost per life saved on scores of regulations. Some health and safety standards have fairly low cost per life saved. For example, car seat belts and airplane cabin fire protection cost about $100,000 per life saved. Automobile side impact standards and the children’s sleepwear flammability ban, at about $1 million per life saved, are also fairly inexpensive. In contrast, the asbestos ban costs $131 million per life saved, regulations concerning municipal solid waste landfills cost about $23 billion per life saved, and regulations on Atrazine/alachlor in drinking water cost a whopping $100 billion per life saved. “A regulatory system based on sound economic principles would reallocate resources from the high-cost to the low-cost regulations. That would result in more lives saved at the same cost to society.”

Sources: W. Kip Viscusi, “Safety at Any Price?” Regulation, Fall 2002: 54–63; W. Kip Viscusi, “The Lulling Effect: The Impact of Protective Bottlecaps on Aspirin and Analgesic Poisonings,” American Economic Review 74(2) (1984): 324–27.

Answer to Try It! Problem

Deregulation of the airline industry led to sharply reduced fares and expanded output, suggesting that supply increased. That should significantly increase consumer surplus. Specifically, the supply curve shifted from S1 to S2. Consumer surplus is the difference between the total benefit received by consumers and total expenditures by consumers. Before deregulation, when the price was B and the quantity was Q1, the consumer surplus was BCD. The lower rates following deregulation reduced the price to consumers to, say, F, and increased the quantity to Q2 on the graph, thereby increasing consumer surplus to FCG.

References

Cohen, A., and Liran Einan, “The Effects of Mandatory Seat Belt Laws on Driving Behaviour and Traffic Fatalities,” Review of Economics and Statistics 85:4 (November 2003): 828–43.

Crain, W. M., and Thomas D. Hopkins, “The Impact of Regulatory Costs on Small Firms,” Report for the Office of Advocacy, U.S. Small Business Administration, Washington, D.C., RFP No. SBAHQ-00-R-0027, October 2001, p. 1.

Peltzman, S., “The Effects of Automobile Safety Regulations,” Journal of Political Economy 83 (August 1975): 677–725.

Viscusi, W. K., “Safety at Any Price?” Regulation, Fall 2002: 54–63.