4 Neuroethics

Welcome to Day Four of the virtual YSP-REACH learning experience! Today you will be exploring the field of study known as neuroethics. Feel free to explore these resources before today’s virtual lecture with an ethicist to develop your background understanding, or afterwards as a way to extend your learning.

Later today, you are invited to join a special online presentation! The Center for Neurotechnology Student Leadership Council is hosting a Neuroethics Panel Discussion from 3:00–4:00 pm. During this discussion, panelists will explore how neuroethical questions are approached in both academic and industry settings and have a conversation about how to incorporate awareness of social issues into neuroscience, neural engineering, and research. Today’s speaker, Dr. Ishan Dasgupta, will be one of the afternoon panelists. You will be sent an email with the link to connect to the online panel.

Today’s learning progression begins with a description of the fields of ethics, bioethics, and finally, neuroethics. You will learn about the principles of bioethics and the specific areas of concern for neuroethics. You will watch a recent TEDx talk by ethicist Dr. Judy Illes as she discusses neuroethical concerns. In today’s CNT Research Highlight, you will read a news article that describes how ethics are a cornerstone of neural engineering research at the Center for Neurotechnology. You will also read a journal article that outlines four major areas of ethical concern for neurotechnologies research and then choose-your-own-adventure by exploring one or more of these areas of concern to explore more deeply. Each of the four options includes a video, reading, and/or case study.

Through readings, videos, reflection questions, case studies, and interactive quizzes, you will explore some of the “sticky” issues faced by engineers, scientists, computer scientists, clinicians, doctors, and ethicists who work in the field of neurotechnology, as well as the end-users and patients of these device, treatments, and therapies. Be on the lookout for career connections as you navigate through today’s materials, including philosophers, ethicists, professors, graduate students, and social science researchers.

Before we can jump in to learning about neuroethics, we need to back up a bit. Let’s begin by thinking about ethics.

PART ONE: WHAT ARE ETHICS?

Ethics are rules or standards that govern thinking, decision making, and behavior, in particular for how we think and act in regards to others. Ethics can also be thought of as a system of moral principles. It is important for researchers, clinicians, and others involved in the development and deployment of neurotechnologies to become ethical practitioners who approach their research and work in principled and responsible ways.

How do ethics differ from morals and values?

The Northwest Association for Biomedical Research explains that,

“The terms values, morals, and ethics are often used interchangeably. However, there are some distinctions between these terms that are helpful to make.

“Values signify what is important and worthwhile. They serve as the basis for moral codes and ethical reflection. All individuals have their own values based on many aspects including: family, religion, peers, culture, race, social background, gender, etc. Values guide individuals, professions, communities, and institutions. One expression of values might be that ‘Life is sacred.’

“Morals are codes of conduct governing behavior. They are an expression of values reflected in actions and practices. Morals can be held at an individual or communal level. For example, ‘One should not kill’ provides a guideline for action based upon values.

“Ethics provides a systematic, rational way to work through dilemmas and to determine the best course of action in the fact of conflicting choices. Ethics attempts to find and describe what people believe is right and wrong, and to establish whether certain actions are actually right or wrong based on all the information available. For example, ethics might address a question such as ‘If killing is wrong, can one justify the death penalty or kill in self-defense?’” (Northwest Association for Biomedical Research, 2012)

(From: “Ethics Background Reading” (pg. 27-28) from the curriculum, Bioethics 101: Reasoning and Justification, Chowning et al., 2012, Northwest Association for Biomedical Research. https://www.nwabr.org/teacher-center/bioethics-101#overview. [Hyperlinks added.])

Reflect on What You Learned

PART TWO: WHAT ARE BIOETHICS?

Bioethics are concerned with the societal issues surrounding biomedical research, new scientific techniques, and new biomedical technologies, devices, and treatments. Bioethicists consider the ethical, legal, and social implications of research, treatments, and technologies. Medical and healthcare ethics are part of the general category of bioethics, though the area of concern is more focused on relationships between physicians and other health care workers and their patients. Also included in the general category of bioethics is public health ethics, environmental ethics, and animal ethics.

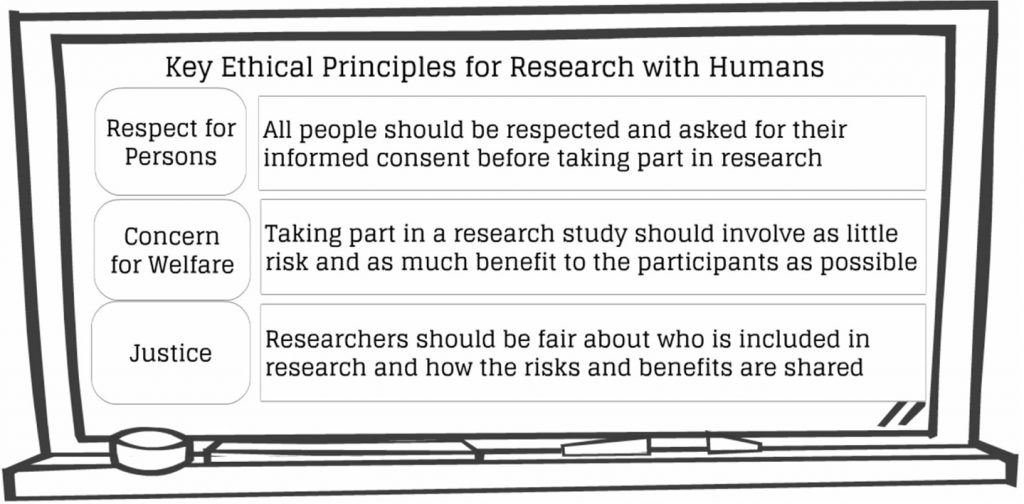

The study of bioethics includes three main principles: respect for persons, maximizing benefits/minimizing harm, and justice. These principles are described by the Northwest Association for Biomedical Research as follows:

“Respect for Persons: This principle values the inherent dignity and worth of each person, as well as respecting individuals and their autonomy. It means not treating people as a means to an end. Autonomy emphasizes the right to self-determination and acknowledges a person’s right to make choices, to hold views, and to take actions based on personal values and beliefs. It emphasizes the responsibility individuals have for their own lives. The rules for informed consent in medicine are derived from the principle of respect for individuals and their autonomy. In medicine, there is also a special emphasis on privacy, confidentiality, truthfulness, and protecting individuals from vulnerable populations.

“Maximizing Benefits/Minimizing Harms: This principle stresses ‘doing good’ and ‘doing no harm.’ To maximize benefits one would directly help others and act in their best interests. It requires positive action. Minimizing harms obligates others to avoid inflicting harm intentionally. It relates to one of the most traditional medical guidelines, the Hippocratic Oath, which requires that physicians ‘do no harm’–even if they cannot help their patients. ‘Doing good’ is also referred to as beneficence, and ‘do no harm’ is also referred to as nonmaleficence. [This principle is also sometimes referred to as Concern for Welfare].

“Justice: This principle relates to ‘Giving to each that which is his due’ (Aristotle) or fairness. It dictates that persons who are equals should qualify for equal treatment, and that resources, risks, and costs should be distributed equally.

“Other Considerations: Some ethicists also add care, which focuses on the maintenance of healthy, caring relationships between individuals and within a community. The principle of care adds context to the traditional principles and can be used alongside them. Additional considerations include duties and responsibilities or taking actions that reflect personal virtues.” (Northwest Association for Biomedical Research, 2012). [Hyperlinks added.]

Reflect on What You Learned

What are the historical roots of bioethics?

Northwest Association for Biomedical explains that these bioethics principles go back in time thousands of years:

“We find references to fairness and justice in Aristotle’s writings. The Hippocratic Oath entreats physicians to ‘First, do no harm.’ The Nuremburg Code was created in response to World War II atrocities in which prisoners were used for experimentation without their consent. The Code helped to define ‘Respect for Persons’ and created guidelines for conducting ethical human clinical trials. The principles were further refined in the 1970s in a document outlining guidelines for research called the Belmont Report. The advent of new life-saving technologies such as the first [kidney] dialysis machines and organ transplants created a need to establish policy regarding the fair distribution of scarce resources, and to understand how to balance the benefits and burdens of this new research.” (Northwest Association for Biomedical Research, 2012)

From: “The Principles of Bioethics–Background” (pg. 28) in “Lesson Two: Principles of Bioethics” from the curriculum, Bioethics 101: Reasoning and Justification, Chowning et al., 2012, Northwest Association for Biomedical Research. https://www.nwabr.org/teacher-center/bioethics-101#overview. [Hyperlinks added.]

PART THREE: WHAT ARE NEUROETHICS?

Neuroethics are a subspecialty within the study of bioethics. In an article for Frontiers for Young Minds, Mc Glanaghy, Di Pietro, and Illes (2015) provide an introduction to the field of neuroethics. They write,

“Neuroethics is a field of study dedicated to understanding the ethical, legal, and social impact of research on and about the brain (i.e., neuro). Neuroethics also aims to better understand the brain processes that are involved in making decisions about what is right or wrong. Ultimately, research in neuroethics seeks to identify solutions to help neuroscience and society come together safely and with the best results.” (Frontiers for Young Minds, 2015).

Watch This!

Watch the following short video, What is Neuroethics?, from the Galactic Public Archives. Then consider the reflection questions provided below. (Note that English closed captioning subtitles are provided, but are auto-generated and not completely accurate).

Reflect On What You Learned

At the end of this short video, the question is asked:

- What would you do with these emerging technologies?

- Should you help people with neurological injuries and disorders? Why or why not?

Consider your own responses to these questions.

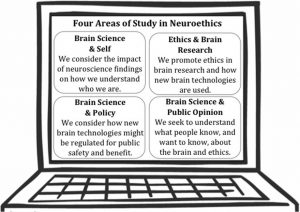

What are the general areas of study within neuroethics?

The field of neuroethics covers a wide variety of ethical issues across the fields of neuroscience, psychology, neural engineering, and neurotechnologies. In their article, McGlanaghy, Di Pietro, and Illes (2015) present four general areas of study within the field of neuroethics, as shown in the figure below. These include: brain science and self; ethics and brain research; brain science and policy; and brain science and public opinion. As we move forward in today’s learning journey, we will focus on neuroethics as it relates to neural engineering and neurotechnologies, within the ethics and brain research category.

Optional Extension

To read about an example of a research study from each of these four areas, visit McGlanaghy, Di Pietro, and Illes’ 2015 article at Frontiers for Young Minds.

Considering the Ethics of Neural Engineering Research and Neurotechnologies

Let’s think a little more deeply about the ethics of brain research in regards to neural engineering and neurotechnologies. In this section, you will watch a TEDx video of a leading neuroethicist as she discusses important neuroethical concerns. You will then read an article about how neuroethicists are embedded into engineering labs at the Center for Neurotechnology, collaborating with engineers throughout the research process.

Watch This!

What do people think about the ethics of conducting brain surgery to treat different neurological and psychiatric conditions? In this TEDx talk, ethicist Dr. Judy Illes discusses neuroethical concerns, including hope versus hype, rights, justice, agency, and personal privacy. Dr. Illes is a Professor of Neurology and Canada Research Chair in Neuroethics at the University of British Columbia. She is also an advisor to the Neuroethics thrust at the Center for Neurotechnology. (Note: English Closed Captions are available).

Reflect On What You Learned

PART FOUR: CNT RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

In today’s CNT Research Spotlight, read two articles to learn how ethicists are collaborating with engineers in the UW BioRobotics Lab throughout the process of developing and employing new neurotechnologies. Note that the Center for Neurotechnology (CNT) was formerly known as the Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering (CSNE), as it is referred to in the second article.

First, read the illustrated article, “Between Humanity and Technology,” and consider the case of Joan, an Army vet who experiences a traumatic injury. This article features the work of CNT neuroethicists Dr. Eran Klein, Dr. Timothy Brown, and Dr. Sara Goering.

Read This!

Read the short article, “Between Humanity and Technology” (May 2020). Consider the question, what makes us human? Where does humanity end and technology begin?

Next, read an article that features PhD students Brady Houston of the Graduate Program in Neuroscience, Maggie Thompson of the Department of Electrical Engineering, and Tim Brown of the Department of Philosophy.

Read This!

Click on the link to read the article “Ethics as a Cornerstone of Neural Engineering Research” (Ansar, 2017).

http://centerforneurotech.org/engage-enable/post/ethics-cornerstone-neural-engineering-research

This second article mentions that these doctoral students also work as graduate research assistants or researchers. When a graduate student is pursuing a PhD, they are often employed by their department as either a Graduate Research Assistant (RA) or a Graduate Teaching Assistant (TA). These positions typically provide a salary (20 hours/week), tuition, and health insurance, allowing students to fund their graduate education while also engaging in meaningful and career building experiences in research and teaching.

Reflect on What You Learned

PART FIVE: ETHICAL CONCERNS WITHIN THE FIELD OF NEUROTECHNOLOGY

Would you like to dig a little deeper into ethical concerns that are specific to the field of neurotechnology? If so, you may want to read an article that introduces four areas of ethical concern within the field of neurotechnologies: privacy and consent; agency and identity; augmentation; and bias. Then, if you want to learn more, choose one (or more) of these areas of concern to explore in more depth through the use of videos, readings, and case studies. Write/journal your answers to the reflection questions.

Begin by reading this article published in Nature in 2017 that calls for ethically responsible neuroengineering. It was written in collaboration by 25 neuroethicists, including those associated with the CNT. This scholarly article has a high reading level, so don’t worry if you don’t understand every term or concept. Just focus on the major points. If you need help, visit the Appendix of this book for tips on reading journal articles.

After reading the article, choose one of the four areas of concern to explore in more depth.

Read This!

Read the article, “Ethical Priorities for Neurotechnologies” (Yuste et al., 2017) by clicking on the link below.

https://www.nature.com/articles/551159a https://www.nature.com/articles/551159a.pdf

Optional: Learn More! Now that you have read the article, “Ethical Priorities for Neurotechnologies,” choose one (or more) of these areas of concern to explore in more depth through the use of videos, readings, and case studies:

- Option 1: Focus on Privacy and Consent

- Option 2: Focus on Agency and Identity

- Option 3: Focus on Augmentation

- Option 4: Focus on Bias

Start the course below to choose your (totally optional) learning adventure. Then share what you learned in today’s Padlet.

Try This!

After exploring the resources provided in one of the options above, respond to this question on a Padlet:

- What area of concern did you explore (Privacy & Consent; Agency & Identity; Augmentation; Bias)? What was one key take-away or emerging question that you have?

Post your responses to this Thoughts on Neuroethical Concerns Padlet. See what other VRP participants have posted as well. You can “favorite” the ones you agree with or add comments.

Then, hit the “back” arrow on your web browser to return to this chapter and keep reading.

Conclusion

Before today, did you realize the important role of philosophy and ethics in the development of neurotechnologies?

Today, you dove into a crash-course focused on understanding the basic principles and areas of concern that are the focus of the field of neuroethics. You’ve considered how neuroethicists collaborate with researchers to consider vexing issues throughout the research process, such as privacy, security, identity, and agency. You have also read accounts that show the truly interdisciplinary nature of neurotechnology research, and seen how engineers, scientists, philosophers, and patients can work together to better understand how to develop and implement neurotechnologies.

Tomorrow, you will focus your learning on college and career pathways that will further emphasize the interdisciplinary nature of the field of neurotechnology. From philosophers, computer scientists, and statisticians, to neurosurgeons, electrical engineers, and physical therapists—neurotechnology offers a cutting-edge field rich with different career opportunities.

Tomorrow we will wrap up this week-long experience by focusing on college and career pathways that can lead to working in the exciting field of neurotechnology. Our guest speaker, Dave Wolczyk, will join us from the University of Washington’s Math Science Upward Bound (UW STEMsub) program.

Citations:

- Mc Glanaghy E, Di Pietro N, and Illes J. (2015). “The Brain and Ethics: An Introduction to Research in Neuroethics.” Front. Young Minds. 3:2. doi: 10.3389/frym.2015.00002. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

- Book/Brain icon made by Smashicons from https://www.flaticon.com.

- Video Play Button icon made by Freepike from https://www.flaticon.com.

- Head/Question icon made by Smashicons from https://www.flaticon.com.

- Artistotle image from Wikimedia Commons https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle#/media/File:Aristotle_Altemps_Inv8575.jpg.

- Photographs of CNT researchers from the Center for Neurotechnology.

- Images of Drs. Klein, Brown, and Goering from the University of Washington.