1 Environmental Health Disparities in Seattle

Madison Powell

You’ve probably heard that Seattle summers make up for the cold, rainy months of the year, with near perfect weather, bright blue skies and views of Rainer. But this past September that was not the case. In early September smoke and ash from wildfires raging in Eastern Washington and Oregon flooded the Seattle area, bringing one of the worst air quality indexes Seattle has ever seen and posing a serious threat to human health amidst a global pandemic.

While climate change isn’t a direct cause of the wildfires seen this past summer, the increasing numbers of fires seen each year are consistent with the changing climate.  Current climate models predict that by the 2040s the Pacific Northwest “could lose up to 1.1 million acres due to wildfires,” (Washington State Department of Ecology). Rising temperatures, dry summers, early snowmelt, and beetle kill all contribute to this statistic. Wildfires add PM 2.5 particles into the air which are pollution particles so small that our body can’t filter them. These particles end up in our lungs and blood stream and impact our health. Exposure to these particles can create mild symptoms such as headaches, irritation of the throat and eyes, but for those with underlying health conditions such as asthma and other respiratory conditions, the effects of the smoke can be much worse, even life-threatening. In low-income communities and communities of color, the risk is even higher. According to the American Lung Association, studies done in the Medicaid-eligible population have shown that “those living in predominantly black or African American communities suffered greater risk of premature death from particle pollution than those in predominantly white communities,” (Disparities) Seattle is no exception.

Current climate models predict that by the 2040s the Pacific Northwest “could lose up to 1.1 million acres due to wildfires,” (Washington State Department of Ecology). Rising temperatures, dry summers, early snowmelt, and beetle kill all contribute to this statistic. Wildfires add PM 2.5 particles into the air which are pollution particles so small that our body can’t filter them. These particles end up in our lungs and blood stream and impact our health. Exposure to these particles can create mild symptoms such as headaches, irritation of the throat and eyes, but for those with underlying health conditions such as asthma and other respiratory conditions, the effects of the smoke can be much worse, even life-threatening. In low-income communities and communities of color, the risk is even higher. According to the American Lung Association, studies done in the Medicaid-eligible population have shown that “those living in predominantly black or African American communities suffered greater risk of premature death from particle pollution than those in predominantly white communities,” (Disparities) Seattle is no exception.

The lack of affordable housing within the city has forced many low-income people to move to the suburbs, often along the highway where exposure to harmful toxins and pollution is higher. The CDC says exposure to traffic pollution can have negative effects on your health such as decreased lung function, cardiovascular disease, and making asthma symptoms worse (Community Design). Increased exposure to traffic pollution in conjunction with wildfire smoke intensified the already existing health disparities within these communities.

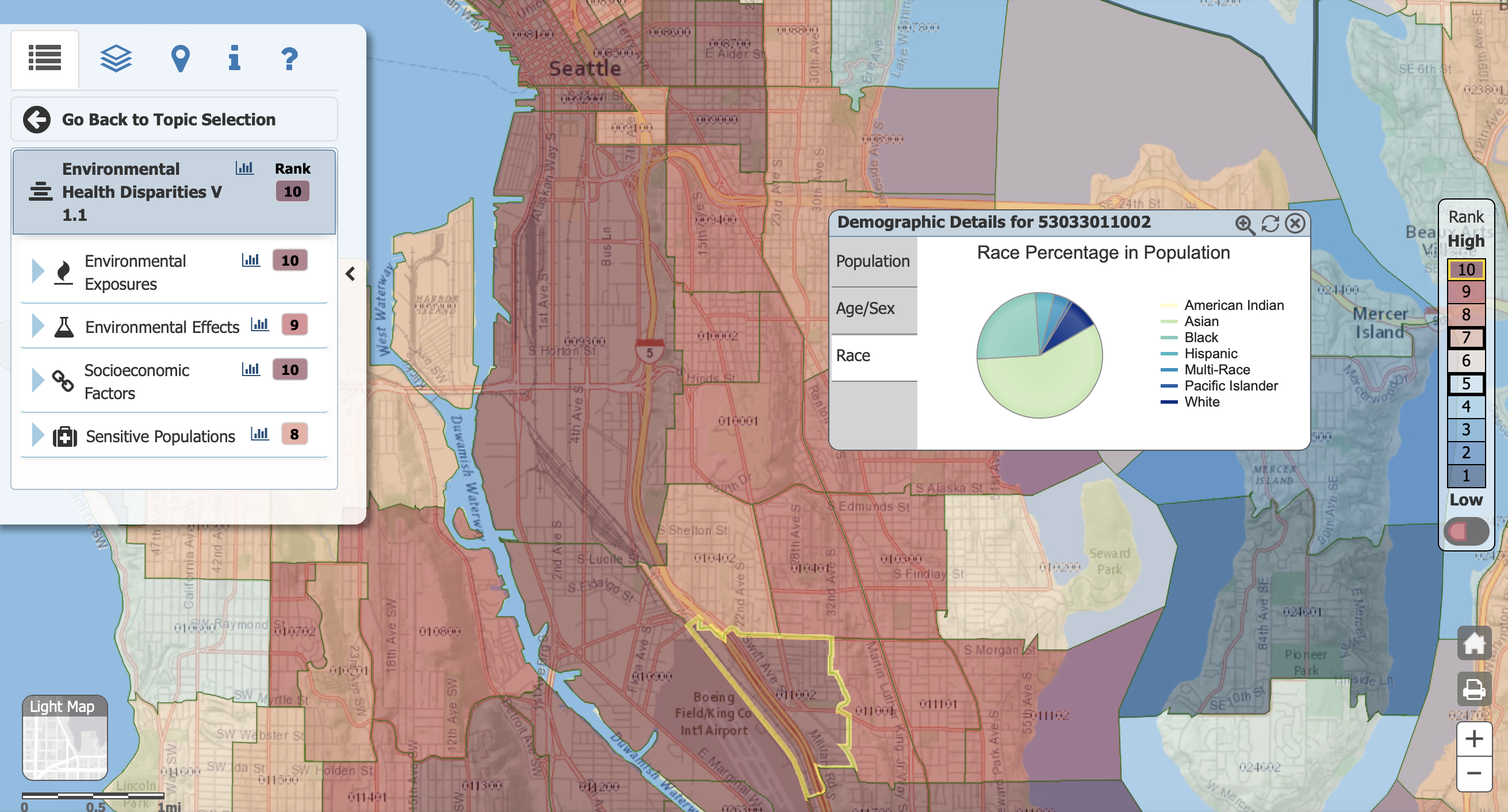

An interactive map on the Washington State Department of Health’s website ranks areas of Seattle on environmental health disparities, with 1 being least impacted and 10 being the most impacted. Environmental health disparities exist when communities are disproportionately impacted by the quality of the environment and therefore have more health problems. The map also shows environmental and socioeconomic factors that contribute to these rankings. One census area near the Boeing airfield and the I-5 highway ranks 10 for environmental disparities. The population of this community is 58% Asian and 25% Black and also has a large population of people living under the poverty level. These populations are already more vulnerable to health problems. In the report Our People, Our Planet Our Power by the Seattle organizations Got Green and Puget Sound Sage, it is stated that “In King County, asthma prevalence among Asian, Black and multiracial youth is higher than white and Hispanic youth,” (Got Green).

Another example of an environmental health disparity is a direct cause of hotter summers. The rising summer temperatures is one of the most apparent impacts of climate change, especially in Seattle. Six of the seven hottest summers in Seattle have occurred in the last seven years. (Sistek) This past summer King County launched a project to map the areas that are impacted the most by the heat. According to King County, “the temperature between city blocks can vary by as much as 20 degrees Fahrenheit due to differences in the amount of paved surfaces and tree canopy,” (Lewis). Hot weather can cause conditions like heat cramps, heat exhaustion, and trigger asthma and cardiovascular problems for those with underlying conditions. The heat also amplifies pollution, worsening respiratory problems and asthma. Escaping the heat can be difficult. Many homes in Seattle don’t have air conditioning and installing air conditioning can be a large cost that many can’t afford. Wealthier neighborhoods in Seattle also have 29% tree coverage compared to 18% in low-income neighborhoods (Got Green). Thus, low-income neighborhoods are disproportionately affected by the heat and the impacts it has on one’s health.

These reasons and many more prove just how important the climate justice movement is, but also the racial

justice movement. Without racial and class justice, climate justice is not real justice, only a false solution. We need to turn our attention to improving our everchanging climate while also ensuring that those in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color aren’t forgotten about, since they are the ones that feel the impacts of climate change the most. Metronome’s clock in Manhattan, New York reads the time we have left before the impacts of climate change become irreversible. 7 years. 7 years until the summers get hotter, the pollution gets worse, sea levels rise, and we can’t do anything about it. The good news is we still have time. Climate change is not just an issue about our planet, but human lives and the health of our communities.

Media Attributions

- Smokey_skyline_view_of_Downtown_Seattle_from_Rizal_Bridge_-_Sept_11,_2020

- wildfire-1826204_1280

- patrick-perkins-jsc8EFVORTA-unsplash

- Screen Shot 2020-12-03 at 10.38.36 AM

- pexels-markus-spiske-2027058