Regular Joes & Betty Coeds — Japanese Students at the UW

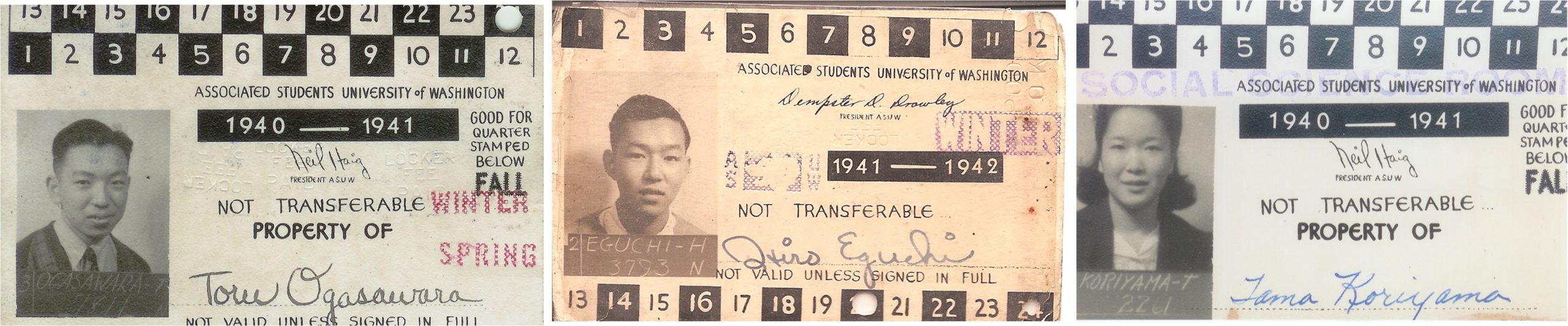

In the fall of 1941, there were over 400 students of Japanese ancestry enrolled at the University of Washington; most were American citizens, or Nisei (second generation); second only to the University of California at Berkeley.[1] They were regular Joes and Betty coeds, indistinguishable from their classmates but for their features and names. They majored predominately in areas of science and business, professions that first-generation parents, the Issei, thought would result in more stable job prospects and economic security.[2] However there were students with interests in more than twenty disciplines, ranging from advertising to nursing and from engineering to pharmacy.[3] As a group, their academic performance was a bit better than the average UW student; many would receive honors in absentia in June of 1942.[4]

College fraternities prior to the 1950s restricted membership either overtly or covertly to Whites with Protestant affiliation. Jews and people of color were not allowed to join. In response Jews, African Americans and Asian Americans formed their own fraternities. On the University of Washington campus, Japanese Americans, excluded from traditional fraternities and sororities, founded their own clubs: the Japanese Student Club (JSC) for men and the Fuyo Kai (Hibiscus Club) for women.

The Japanese Student Club was founded in 1922 under the name University Students’ Club. Membership was not restricted by race, nationality or creed. A clubhouse, funded by donations from Japanese Americans, was purchased across the street from campus. The clubhouse provided a lounge as well as a dormitory for out-of-town students.[5]The JSC was for all intents and purposes a social fraternity. The 1926 Quarterly, a club publication, stated that “The Japanese Students’ Club has come to mean the center of Japanese student life, as Eagleson Hall, the International House, Tillicums, the fraternities and the sororities are the center of the student life of the varigated groups on the campus.“[6]

Fuyo Kai was established in 1925, succeeding an earlier group, the Japanese Progressive Women’s club (1921 – 1925). The Constitution of Fuyo Kai stated three goals: 1) “to bring together the Japanese Women students into closer relationship,” 2) “to attain a better understanding of the highest ideals of Japan and America and 3) “to be an instrument of service to our Alma Mater.”[7]

The usual activities were held: monthly meetings, dances with the JSC, panhellenic dinners, quarterly pledge initiations, and spring teas. The sole surviving copy of the club newsletter, Fuyo-Kai Fulcrum, at the University of Washington archives, resonates with quintessential themes of coed life of the early 1940s such as music (White Cliffs of Dover is the favorite), fashion (“When betty co-ed wants to turn all her glamour on her boyfriend she can wear a black velveteen date frock…”) and romance (“the boys we’d like to kiss goodbye”).[8] In this issue, initiation antics are featured in full, light-hearted detail:

BRIEFS FROM THE JSC INITIATION: BEEFO AMABE crawling on his stomach on a “corn flaked” floor. SHO NOJIMA passing out from the limburger and marshmallow combination. Bashful fellows like RICHARD IMAI having to get thirty Fuyo-Kai gal’s signatures. YOSH HONKAWA’S looking like Dagwood Bumstead in his bow tie. AL OUCHI reading poetry to a certain miss….under the watchful eyes of ABE HAGIWARA and GEORGE KOSAKA. SAM SAKAI having to don a red bow tie.[9]

On December 5, 1941, two days before Pearl Harbor, the Fuyo Kai sponsored a “Draftee Party” for Japanese American soldiers from Fort Lawton and Fort Lewis. The minutes from December 5th note that “60 army men were present.”[10]

In addition to membership in the JSC and Fuyo Kai, Nisei students also participated in scholastic societies and clubs such as Phi Beta Kappa, Pi Mu Chi, the Home Economics Club, and the YMCA and YWCA.[11] Some were lettermen — Joe Kesamura in baseball, Tad Fujioka in swimming, and Frank Watanabe in tennis.

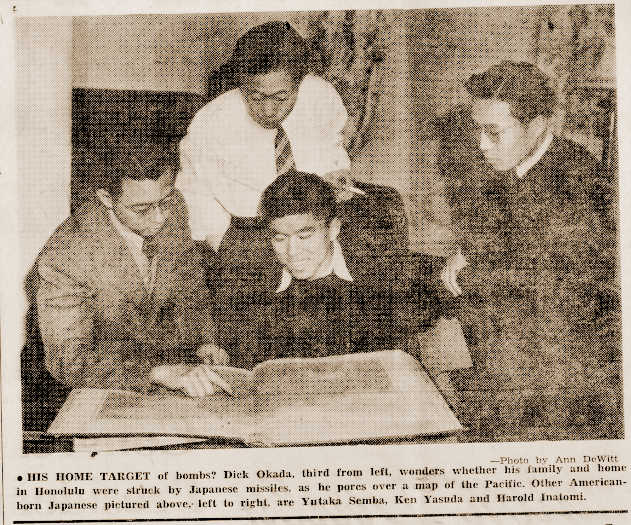

All this changed with the attack on Pearl Harbor. On the evening of December 7 the FBI began to round up community leaders and police departments raided homes for contraband such as shortwave radios, hunting rifles and samurai swords. By December 9 more than 1,200 people of Japanese descent were in custody nationwide.[12] The arrests caused panic amongst the Japanese American community. According to Reverend Daisuke Kitagawa of St. Paul’s Church outside Seattle, “every male lived in anticipation of arrest by the FBI, and every household endured each day in fear and trembling.”[13]

UW student Dick Takeuchi was sent out to report the reactions of fellow Japanese American students to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. His article in the special war edition of the Daily is filled with exclamations of shock and disbelief. Students were also keenly aware of the possible ramifications of war between the United States and Japan. In a prescient moment the term “concentration camp” appeared in print:

UW student Dick Takeuchi was sent out to report the reactions of fellow Japanese American students to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. His article in the special war edition of the Daily is filled with exclamations of shock and disbelief. Students were also keenly aware of the possible ramifications of war between the United States and Japan. In a prescient moment the term “concentration camp” appeared in print:

As war, or undeclared war became a reality, the shock to these students was reflected and magnified in their parents, most of whom are Japanese citizens. That their parents may be confined in a concentration camp while they faced discrimination and suspicion was held not impossible by many of the students.

“We hoped at first that it was German raiders. It’s still unbelievable.”

Such was the first reaction of American-born Japanese University students who sat huddled around the radio in their clubhouse last night, and utterly bewildered, tried to imagine that the country of their ancestors had actually attacked the United States.[14]

In the early days after Pearl Harbor, many church groups and universities united behind their Japanese American students. University of Washington President Lee Paul Sieg stated in the Japanese American Courier, “I am confident that the great majority of [Japanese Americans] will join with all Americans, regardless of ancestry, origin, creed or color, to bring this conflict to a successful conclusion.”[15]

Despite the calls for tolerance and support for the Nisei, Mike Masaoka, national secretary of the Japanese American Citizen’s League (JACL) warned:

Just because many of the restrictions are being relaxed, we must not dismiss the troubles of the past month as horrible nightmares and confidently await a return to our former status. The longer the war drags on — as casualty lists are published, West Coast cities are shelled or bombed, atrocities committed — the tougher our situation will become. Public sympathy may wear away, perhaps hate and prejudice will replace the present tolerance and forbearance.

We must gird our loins, tighten our belts and prepare for the hardest fight in our generation, a fight to maintain our status as exemplary Americans, who, realizing that modern war demands great sacrifices, will not become bitter or lose faith in the heritage which is ours as Americans, in spite of what may come; a fight that will not be won in a week, or months, or even years; a fight which will test our mettle and our courage; a fight in which we must make heroic sacrifices equal to those made on the battlefield, but also a fight in which we will be subjected to suspicions, persecutions, and possibly downright injustices.[16]

For Japanese Americans, Pearl Harbor and World War II were watershed events, affecting issues of identity, culture and generational change. Ties that the Issei (the first generation of immigrants) maintained with their ancestral home through business and cultural associations, familial interactions, and the use of the Japanese language, now became suspect. The Nisei, their children, by virtue of their American citizenship became almost overnight the leaders within the Japanese American community while the Issei were relegated to the sidelines (if not already detained by the police and FBI). Frank Miyamoto, an associate in the Department of Sociology, acknowledged this transferral of power in an article entitled “War Places Second Generation in Lead Once Taken by Elders,” published in the Japanese American Courier: “Well, here it is at last. But where do we go from here, in particular, where do we Nisei go from here?”[17]

- Figures ranged from 372 to 458. See: Japanese American Students in the United States, 1942; Lincoln Kanai and Japanese Young Men's Christian Association papers, 1942, California Historical Society. "435 Japanese at the U.W.; Only 11 Alien-born," Seattle Times, March 5, 1942. Bulletin (Student Relocation Committee (Berkeley, Calif.)), no. 2 (May 16, 1942); Joseph R. Goodman papers on Japanese American incarceration, MS-840; California Historical Society. Robert W. O'Brien, "The Changing Role of the College Nisei during the Crisis Period: 1931-1945" (PhD diss., University of Washington, 1945). ↵

- "That was the pressure among pre-war Japanese, that you had to get an education in a readily marketable area. So it would be either medicine, law was not quite as promoted, but certainly medicine was, you’d become a doctor and be bound to have economic security." Kenji Okuda, interview by Louis Fiset, August 9, 1995. Complete interview transcript. ↵

- Information Concerning American Born Japanese Students Facing Evacuation, 8 April 1942, Correspondence Series, Nisei folder, Ernest H. Wilkins Collection, Oberlin College Archives. ↵

- The grade point average in 1941 of Japanese American men was 2.520 and 2.716 for women (the mean for the university as a whole was 2.534). Robert W. O'Brien, "The Changing Role of the College Nisei during the Crisis Period: 1931-1945" (PhD diss., University of Washington, 1945), 15. For information on honors, see "Nisei Students Win Many Honors at Washington U," Pacific Citizen, June 4, 1942. ↵

- "University of Washington Nikkei reunion: commemorating the 75th anniversary of the University Students Club, (1922-1997)," (Seattle: University Students Club, 1997). During the war, the clubhouse was re-christened as International House where American students as well as those from Canada, China, Cuba, and the Philippines lived. "International House Opens." Pacific Cable vol. 1, no. 8 (21 Oct. 1942). After World War II, the clubhouse was renamed SYNKOA to commemorate members who were killed during the war. Each letter represented the surname of a former member: George Katsuya Sawada, Frank Masao Shigemura, George Yamaguchi, Hideo Heidi Yasui, Shigeo Yoshioka, William Kenzo Nakamura, Ban Ninomiya, Jero Kanetomi, Yoshio Kato, John Ryoji Kawaguchi, Francis T. Kinoshita, Takaaki Okazaki and Eugene Takasuke Amabe. Nikkei World War II Memorial Honor Role, University Students Club, Acc. 1853-002, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- Japanese Student Club Quarterly, Fall 1926, UW Japanese Students Club, Acc. 1853-002, UW Libraries Special Collections. This is the only issue in the collection. ↵

- The close tie and cross-membership between the Japanese Progressive Women's Club and Fuyo Kai is evident in the minutes of the organization. Fuyo Kai minutes follow those of the Japanese Progressive Women's Club (JPWC) in the same book of minutes. The final note in the JPWC minutes states "A new organization to be formed for University girls only." The Fuyo Kai constitution and minutes of both organizations are available in Fuyo Kai, Acc. 80-26, UW Libraries Special Collections. Photograph from A Reunion Celebration of University of Washington Pre World War II Japanese American Women Alumnae, available in Fuyo Kai, Acc. 4363, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- Fuyo Kai Fulcrum, February 6, 1942, Fuyo Kai, Acc. 4363, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- "The Facts," Fuyo Kai Fulcrum, February 6, 1942, page 3. Fuyo Kai, Acc. 80-26, UW Libraries Special Collections. Only this single issue is available in the collection. ↵

- Minutes, 5 December 1941, Fuyo Kai, Acc. 4363, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- Japanese American members of various clubs and organizations: Phi Beta Kappa (Fumio Yagi), Beta Gamma Sigma (Kiyoshi Yamashita and Martin Hirabayashi), Sigma Xi (Kazuo Kimura), Totem Club (Kiyoshi Kamikawa), Pan Xenia (Kiyoshi Yamashita, Martin Hirabayashi, Ryo Humasaka, Takashi Matsui, Andrew Morimoto, George Mukasa, Ken Sekiguchi, Tom Uyeno, Hiroshi Yamada, Ken Yorita), Home Economics Club (Yuri Fujii), Sigma Epsilon (Ruby Inouye, Kazuko Umino), Omicron Nu (Chiyeko Kiyono, Yoshiko Uchiyama), Pi Mu Chi (Minoru Araki, Norio Higano, Bryan Honkawa, Kazo Kimura, Eichi Koiwai, Haruo Kumaskura, George Kumasaka, George Sawada, Frank Shimizu, Ben Uyeno) and YWCA and YMCA (Lily Yuri Yorozu, Chiyo Nakata, Kenji Okuda, Norio Higano, Gordon Hirabayashi, David Miyauchi, William Makino, Seiki William Noro, Kazuo Tada, Tom Tamura, Howard Watanabe, Robert Yamauchi, Will Yasutake). Names gleaned from the University of Washington Tyee, 1942. Membership in the honorary societies was low but grew in proportion to the number of students. For example there were four Japanese American students in Phi Beta Kappa in 1942, four in Zeta Mu Tau and three in Sigma Epsilon Sigma. Robert W. O'Brien, "The Changing Role of the College Nisei during the Crisis Period: 1931-1945" (PhD diss., University of Washington, 1945). ↵

- Gary Okihiro, Storied Lives: Japanese American Students and World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999), 23. ↵

- Daisuke Kitagawa, Issei and Nisei: The Internment Years (New York: Seabury Press, 1967), 41. ↵

- Dick Takeuchi, "Can't Believe It's True — Japanese Students," University of Washington Daily, War Extra, Dec. 8, 1941. ↵

- Lee Paul Sieg, "Chance to Assert Loyalty Cites Sieg," Japanese American Courier, Jan. 1, 1942, p. 1. In the same issue, Berkeley President Robert Gordon Sproul, took a more vigorous stand: "The American citizen of Japanese ancestry is likely to be discriminated against because of superficial physical characteristics that have no influence whatsoever on the quality of his mind, the strength of his character, or the depth of his loyalty to the United States." Robert Gordon Sproul, "University Head Asks Confidence." ↵

- Mike Masaoka, "Let This Be Our Vow for 1942: To Serve America," The Pacific Citizen, January 1942. ↵

- Frank Miyamoto, "War Places Second Generation in Lead Once Taken by Elders," Japanese American Courier, January 1, 1942. ↵