4 Accrual Accounting

ACCRUAL ACCOUNTING: GETTING TO THE NUMBERS

Information from financial statements helps managers answer many crucial strategic questions:

- How have this organization's past decisions about fundraising, investing in new property and equipment, and launching new programs shaped its current financial position?

- How might the timing of a key management decision – such as selling a building or hiring a new staff member – affect this organization's financial position?

- How do accounting policy choices regarding depreciation methods, allowances for uncollectable, expense recognition, and other areas affect this organization's financial position?

- How should this organization recognize in-kind contributions of goods and services and volunteer time?

- Why is a government's government-wide financial position different from the position in its governmental funds? Or its enterprise funds?

- Why are this organization's long-term liabilities portrayed differently in its financial statements compared to its fund statements?

The City of Rochester, NY, is like most “Rust Belt” cities. It was once a global center of manufacturing, but since the mid-1980s, it has shed thousands of manufacturing jobs. Tax revenues have lagged, and the City’s overall financial position has slowly eroded. The mayor and other local leaders have invested substantial public resources in local programs for the past two decades to promote economic and community development.

Communities like Rochester face a financial dilemma. Some local leaders believe the city should do much more to promote economic and community development. Despite its financial problems, Rochester does have one key financial strength: a comparatively low debt burden ($775/capita). Unlike many of its peers, it has not issued a lot of bonds or other long-term debt that it will need to repay over time. Some leaders believe it could borrow money to invest in infrastructure projects that would spur economic growth, grow the tax base and, in effect, pay for themselves. Or at least that’s the theory.

Others disagree. They concur that the city has carefully managed its borrowing and does not owe investors much money. However, they point out that Rochester has an enormous amount of “other” long-term debts ($3,927/capita). Principal among them is “other post-employment benefits” or OPEB. Like many of its peers, Rochester allows its retired city workers to remain on its health insurance plan. Moreover, it pays most of the insurance premiums for those retirees and their families. Many thousands of retired City workers are expected to take advantage of this benefit for years to come.

Under governmental accounting rules, the money Rochester expects to spend on OPEB benefits over the next 30 years must be recognized as a long-term liability today. Those rules follow from the idea that employees earn OPEB benefits as part of their salary. Once earned, those benefits become a liability that appears on the City’s balance sheet. Rochester can change those benefits at any time, but until they do, they remain a long-term obligation of the government.

This anecdote highlights one of the key points of this chapter: How we account for – or “recognize” – financial activity can have a major impact on how an organization perceives its financial strengths and weaknesses and how it might choose to manage its finances in response. That is why all public managers must not only know how to analyze financial statements but also understand the origins of the numbers that appear in those statements. In other words, they need to know a bit of accounting. That is the focus of this chapter.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand how typical financial transactions affect the fundamental equation of accounting.

- Recognize revenues and expenses on the accrual basis of accounting.

- Contrast an organization's assets and liabilities with its revenues and expenses.

- Prepare rudimentary versions of the three basic financial statements.

- Understand how routine financial transactions shape an organization's basic financial statements.

- Contrast the recognition concepts in accrual accounting with cash accounting and fund accounting.

CORE CONCEPTS OF ACCOUNTING

Now that we’ve toured the basic financial statements let’s take a step back and review how we produce those statements. Financial statements are useful because they're prepared according to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). To understand financial statements, you must know a few of those principles and how typical financial transactions shape the numbers you see in those statements. This section covers both these topics.

THE ACCRUAL CONCEPT

Most of us organize our personal finances around the cash basis of accounting. When we pay for something, we reduce our bank account balance by that amount. When we receive a paycheck, we increase our bank account balance by that amount. In other words, we recognize financial activity when we receive or spend cash.

Many small organizations also use cash basis accounting. Many small non-profits and governmental entities (e.g., irrigation districts and mosquito abatement districts) keep separate books to track revenues received and other operating expenses paid.

But for larger and more complex organizations, cash basis accounting tells an incomplete story. For instance, imagine that Treehouse (the organization in our previous examples) plans to purchase $20,000 of furniture for its main office. Treehouse will purchase that equipment on credit. That is, they will order the equipment, the supplier will deliver that equipment and send an invoice requesting payment, and a few weeks later, Treehouse will write the supplier a check and pay off that invoice.

This transaction will have an impact on Treehouse’s balance sheet. It will draw down its cash and report a fixed asset that will stay on the organization’s balance sheet for several years. Treehouse’s stakeholders should know about this transaction sooner rather than later.

But on a cash basis, those stakeholders will not know about this transaction until Treehouse pays off the invoice. That might be several weeks away. If it is toward the end of the fiscal year – and several large purchases happen toward the end of the fiscal year – those transactions will not appear on Treehouse’s financial statements until the following year. That is a problem.

That is why most public organizations use the accrual basis of accounting. On an accrual basis, an organization records an expense when it receives a good or service, whether or not cash changes hands. In this case, as soon as Treehouse signs the purchase order for the equipment, that purchase will appear as a $20,000 increase in non-current assets on its balance sheet. It will also record – or recognize, in accounting speak – an account payable for $20,000. On the accrual basis of accounting, we can see how this transaction will affect Treehouse's financial position now and in the future.

Keep in mind that accrual accounting assumes the organization is a going concern. That is, it assumes the organization will continue to deliver services indefinitely. If we are not willing to make that assumption, then accrual accounting does not add value. In some rare cases, the audit report will suggest that the auditor believes the organization is not a going concern. In other words, the auditor believes the organization’s financial position is so tenuous that it might cease operations before the close of the next fiscal year.

We can apply similar logic to the revenue side. Imagine that Treehouse staff run a day-long outreach program at a local school. The program sensitizes public school teachers about the unique challenges facing children in the foster care system. They typically charge $2,500 for this type of event. Assume that Treehouse staff deliver the program and then send the school district a bill for their services. Treehouse used a lot of staff time, supplies, travel, and other expenses to produce this program, but they might not get paid for it for several weeks.

On a cash basis, it will be several weeks before we know about expenses incurred and that Treehouse has earned $2,500 in revenue. But on an accrual basis, Treehouse would recognize expenses incurred and the revenue earned immediately after delivering the program.

In accrual accounting, revenues are recorded when entitled, irrespective of receipt of payment, and expenses are recorded when resources are used, irrespective of when payment is made.

These two simple transactions illustrate a key point: If the goal of accounting and financial reporting is to help stakeholders understand an organization's ability to achieve its mission, then accrual accounting is far better than cash accounting. That's why the accrual concept is a central principle of GAAP. From this point forward, we will focus exclusively on how to apply accrual accounting to public organizations.

THE GENERAL LEDGER AND CHART OF ACCOUNTS

A chart of accounts lists all the organization's financial accounts, along with definitions that clarify how to classify or place financial activity within those accounts. When accountants record a transaction, they record it in the organization's general ledger. The general ledger is a listing of all the organization's financial accounts. When the organization produces its financial statements, it combines its general ledger into aggregated account categories. Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) produced by FASB and GASB do not specify a uniform chart of accounts, so account titles and definitions will vary across organizations. Some state governments require non-profits and governments to follow such a chart, but for the most part, public organizations are free to define their chart of accounts on their own.

RECOGNITION AND THE FUNDAMENTAL EQUATION

Accountants spend much of their time on revenue and expense recognition. When accountants recognize a transaction, they identify how it affects the organization’s financial position. We recognize transactions relative to the fundamental equation of accounting.

The fundamental accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Net Assets, must remain balanced following every transaction. In other words, the net effect of any transaction on the fundamental equation must be zero. This is also known as double-entry bookkeeping. Consider the previous example:

Transaction 1a: Treehouse signs a purchase agreement with Furniture Superstores, Inc. for $20,000 in office furniture and equipment. It agreed to pay for the purchase within 30 days.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Equipment | + $20,000 | Accounts Payable | + $20,000 | ||

Here, we recognize (or "book") the purchase of furniture and equipment on the asset side of the accounting equation. We also need to book an equivalent amount on the liability side to recognize that we’ve received a good, but payment has not been made. The liability account – Accounts Payable – recognizes monies owed to Furniture Superstores. This transaction adds to both sides of the fundamental equation, so the net effect on the equation is zero.

The purchase of furniture and equipment results in an increase in a non-current asset (equipment). Amounts due to Furniture Superstores are a current liability, as Treehouse expects to pay it off within the fiscal year (in this case, 30 days). As a result of this transaction, the non-profit is less liquid. Note that the impact of a transaction depends on the size of the organization’s current or non-current assets. The transaction will be meaningful if the organization is small but insignificant if the organization is large.

What happens three weeks later when Treehouse pays for the equipment?

Transaction 2: Treehouse pays the invoice for equipment received in Transaction 1.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Equipment | - $20,000 | Accounts Payable | - $20,000 | ||

This transaction decreases both sides of the equation. The decrease in cash balances represents payments to the supplier (accounts payable).

Organizations execute a wide variety of transactions in their day-to-day operations. For most transactions, you can identify the correct accounting recognition by asking a few simple questions:

- Did the organization deliver a good or service?

- Did the organization receive a good or service?

- Did the organization make a payment?

- Did the organization receive a payment?

If the organization delivers or receives a service, the transaction affects revenues and expenses. Note that revenues will increase net assets, and expenses will decrease in net assets. If the organization delivered or received a good, the transaction likely affects assets, liabilities, or net assets (as either revenues or expenses). More importantly, whether or not the transaction affects a liability has to do with whether a payment was made or a payment was received.

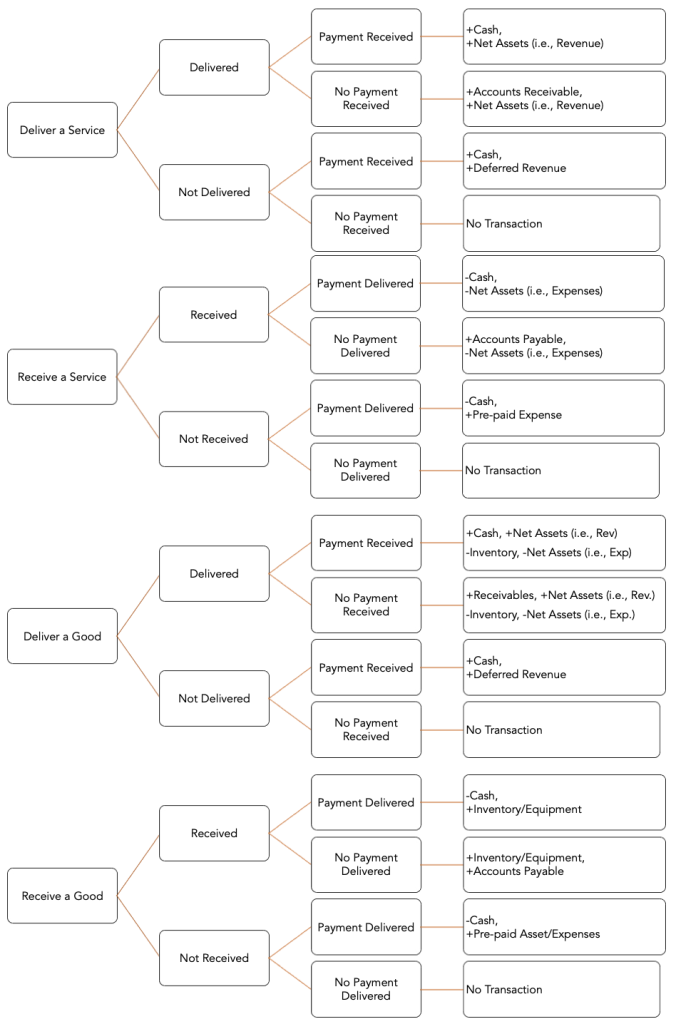

The chart below presents these concepts as a flow chart. Take Transaction 1 as an example. Recall that Treehouse agreed to purchase furniture and equipment and pay for it later. Has it received a good or service? Yes, it has received a good, but it has yet to make payment; as a result, we report an increase in equipment and a corresponding increase in accounts payable.

To reference the flow chart, identify whether the organization was receiving or delivering a good or service and whether payment has been made. We know Treehouse received the equipment order, but payment has yet to be made. Therefore, this transaction starts on the bottom left corner of the chart at “Receive a Good.” We know goods have been received, but payment has not been made. We, therefore, follow the “Payment Not Delivered” line of the flow chart. We would recognize this transaction as an increase in equipment and accounts payable since Treehouse will pay for this equipment later.

TRANSACTION FLOW CHART

With this framework, we can do accounting recognition for most basic transactions. That said, governments and non-profit organizations have unique rules that apply just in those contexts. We will cover nuanced accounting rules in the discussion that follows. That said, always remember:

The fundamental accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Net Assets, must remain balanced following every transaction.

TRANSACTIONS THAT AFFECT THE BALANCE SHEET

Transaction 1 and Transaction 2 are good examples of financial activity that affects the balance sheet. You should be aware of a few others. Some transactions affect only the asset side of the equation. For instance, imagine if Treehouse had purchased the equipment with cash rather than on credit.

Transaction 1b: Treehouse pays for the purchase of $20,000 in furniture and equipment in cash.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Equipment | + $20,000 | ||||

| Cash | - $20,000 | ||||

In Transaction 1a, Treehouse purchased office furniture on credit, so we recognized in that transaction an increase in a liability account – accounts payable. In Transaction 1b, Treehouse paid for the purchase of equipment in cash. The transaction resulted in a decrease in cash and an increase in equipment. As we noted earlier, the net effect of any transaction on the fundamental equation must be zero, even when no liability account or net asset account was affected. Now assume the transaction was as follows:

Treehouse signs a purchase agreement with Furniture Superstores, Inc. for $20,000 in office furniture and equipment. It paid for the purchase of equipment upon delivery.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Equipment | + $20,000 | Accounts Payable | + $20,000 | ||

| Cash | - $20,000 | Accounts Payable | - $20,000 | ||

While we report two separate transactions here – the first being the purchase of equipment on credit and the second being the payment to the supplier – the net effect of this transaction would be an increase in equipment and a decrease in cash – the same as what we reported in Transaction 1b.

Like most organizations, Treehouse likely purchases a wide variety of services that it uses later. Examples include insurance, certifications, subscriptions, and professional association memberships. Treehouse will purchase these services in advance and then use or “expense” them throughout the fiscal year. These are known as pre-paid expenses. For example:

Transaction 3: Treehouse pays $1,500 for three of its staff to renew their annual memberships to the National Association for Social Workers.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | - $1,500 | ||||

| Pre-paid Expense | + $1,500 | ||||

Organizations like Treehouse almost always have financial assets. Assets like buildings and equipment are tangible; they have physical substance. Intangible assets include intellectual property, copyrights, patents, trademarks, goodwill, and software. While rare, public organizations do report intangible assets.

Financial assets are in between tangible assets and intangible assets. While they are not physical assets, they are a claim of ownership or a contractual right to payment. If Treehouse holds Boeing stock, they have a right to dividends the corporation distributes to shareholders. Treehouse can also sell some or all of its Boeing stock, invest proceeds in the organization, or purchase alternative financial investments. So even though Boeing stock is not a tangible asset, it is valuable.

We account for financial assets differently. If Treehouse purchases supplies or equipment, it will record those supplies at historical cost. Supplies or the equipment purchased are valuable because they help Treehouse deliver programs and services. They are not, however, as valuable as a financial investment. That is, we do not purchase inventory in the hope that it would appreciate in value. That is why the historical cost is the appropriate way to value most of Treehouse’s non-financial assets.

Financial assets are different because they are, by definition, purchased to generate income. Treehouse purchased Boeing stock because it expects Boeing to pay dividends to shareholders and the value of the stock to increase over time. If we want to know if investments added value to Treehouse’s mission, the organization’s accounting records need to reflect the market value of those investments at the end of each financial period. If those investments became more valuable, they are contributing to the mission. If they have lost value, they are taking resources away from the mission.

That is why we record financial assets at fair value rather than historical cost. Fair value means the current, observed market price. Investments the organization intends to hold for less than a year that can be converted to cash are known as marketable securities. Investments the organization plans to hold longer than one year or those that are less liquid are known simply as investments. Marketable securities are current assets. Investments can be classified as either a current or a non-current asset.

When an organization puts money into an investment, we record that investment at the purchase price. In that sense, at the time of the initial investment, fair value is the same as historical cost. For example:

Transaction 4a: Treehouse purchased 500 shares of Boeing stock on July 1, 2019, at $350.11 per share.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | - $175,055 | ||||

| Investments (Boeing) | + $175,055 | ||||

The value of any investment portfolio will change unpredictably throughout the financial period. Since these assets generate investment income, we need to reflect the change in the investment value in our accounting records.

An increase in value would be reported as a gain, whereas a decrease in value would be reported as a loss. If Treehouse decided to sell the stock, the gain or loss in the investment value would be reported as a realized gain or loss. If Treehouse still owns its interest in the stock but the value of that stock has changed, that gain or loss in value of the investment would be reported as an unrealized gain or loss. The increase or decrease in value is recorded as a change in net assets. For example:

Transaction 5a: Treehouse sold its 500 shares of Boeing stock on June 30, 2020, at $194.49 per share.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $97,245 | Net Asset (Realized Loss) |

- $77,810 | ||

| Investments (Boeing) | - $175,055 | ||||

In Investments, we record the sale of these assets at historical cost ($175,055) and deposit the proceeds from the sale in Cash ($97,245). On the Net Asset column, we report realized loss from the sale of the stock (i.e., $175,055 – $97,245 =$77,810).

A realized loss has roughly the same effect on the organization’s financial position as an unprofitable program. Both result in a decrease in Treehouse’s overall net assets and available resources or assets. In contrast, if:

Transaction 4b: Treehouse purchased 100 shares of Amazon stock on July 1, 2019, at $1,922.19 per share.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | - $192,219 | ||||

| Investments (Amazon) | + $192,219 | ||||

and

Transaction 5b: Treehouse sold its 100 shares of Amazon stock on June 30, 2020, at $2,680.38 per share.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $268,038 | Net Asset (Realized Gain) |

+ $75,819 | ||

| Investments (Amazon) | - $192,219 | ||||

In Investments, we record the sale of these assets at historical cost ($192,219) and deposit the proceeds from the sale of the asset in Cash ($268,0385). On the Net Asset column, we report realized gain from the sale of the stock (i.e., $268,038 - $192,219=$75,810).

DIVERSIFIED INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO

Boeing and Amazon stock are included in this discussion for illustrative purposes only. In practice, Treehouse, like most other non-profits, does not hold individual stocks or bonds but instead invests in mutual funds. Mutual funds pool money from multiple investors and invest in a diversified portfolio of financial instruments.

Mutual funds diversify on the basis of sector (e.g., technology, financial, retail, consumer, materials, healthcare, utilities), geography (e.g., domestic, emerging markets, developed markets), size of firm (large – >$10 billion – versus small – <$2 billion), and investment type (e.g., public equity, private equity, corporate bonds, municipal bonds, and treasury bonds) to name a few. Investing in mutual funds has the benefit of maximizing returns while mitigating risk at significantly lower investment management fees.

Fair value accounting is a bit more complex – and interesting! – than historical cost because it requires organizations to restate the value of their financial assets at the end of every fiscal period. For Treehouse, this means it would restate the value of all financial investments at the end of each year, even if it did not sell these investments.

If the stock’s price at the time of the re-statement is higher than the previously recorded price, Treehouse will record an increase in investments on the balance sheet and an unrealized gain on the income statement. If the stock’s price at the time of re-statement is lower than the previously recorded price, Treehouse will need to record a decrease in investments on the balance sheet and an unrealized loss in the income statement.

Transaction 6: Treehouse recognizes unrealized gains and losses in Amazon and Boeing stock at the end of FY 2020.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Investments (Amazon) | + $75,819 | Net Asset (Unrealized Gain) |

+ $75,819 | ||

| Investments (Boeing) | - $77,810 | Net Asset (Unrealized Loss) |

- $77,810 | ||

Unrealized gains and losses do not directly affect the amount of cash reported – hence why they are euphemistically referred to as paper gains and paper losses. Notwithstanding, unrealized gains or losses matter, as they represent a real change in the value of financial assets and the resources in an organization. If Treehouse's holdings of Amazon stock contribute substantial unrealized gains for several years, management might consider selling its holdings to realize gains and invest in programs, equipment, or facilities.

PRACTICE PROBLEM: REALIZED AND UNREALIZED GAINS ON INVESTMENTS

The National Breast Cancer Foundation (NBCF) has a large investment portfolio whose income is used to subsidize the non-profit’s operations. At the start of FY 2020 (i.e., July 1, 2019), NBCF reported $14,780,000 in investments. Over the next 12 months, NBCF transferred $1,650,000 from cash to investments. It received $450,000 in investment income (i.e., dividend and interest income).

At the end of the year, the investment manager reported realized losses of $175,000 and unrealized gains of $1,250,000.

The investment manager invoiced NBCF $135,000 for investment management services rendered in the year. NBCF paid these in full.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | -$1,650,000 | Loan Payable (current) |

+$6,000 | ||

| Investments (Transfer of funds from cash to investments) |

+$1,650,000 | Loan Payable (non-current) |

+$24,000 | ||

| Cash | +$450,000 | Net Asset Without Donor Restriction (Investment Income) | +$450,000 | ||

| Assuming the non-profit received direct payment of interest and dividends that would be reported in cash. If the investment manager receives payment on behalf of the organization, that income would be reported under investments. For simplicity, we assume NBCF received payments directly. | |||||

| Investments | -$175,000 | Net Asset Without Donor Restriction (Realized Loss - Investments) | -$175,000 | ||

| Investments | +$1,250,000 | Net Asset Without Donor Restriction (Unrealized Gain - Investments) | +$1,250,000 | ||

| Realized loss lowers the balance in the investment account and unrealized gains increase the balance in the investment account. | |||||

| Investment Manager | +$135,000 | Investment Manager Fee | -$135,000 | ||

| Cash | -$135,000 | Investment Manager | -$135,000 | ||

| Investment managers invoiced NBCF for services provided. The non-profit would report the fee as an expense and make a payment. The investment manager's fees would not be recorded as a payment from investments. | |||||

Assuming there were no restrictions on investment income, how much did NBCF report in investment income (net of expenses) at the end of FY 2020?

= Dividend & Interest Income + Unrealized Gain (or Loss) + Realized Gain (or Loss) – Management Fee

=$450,000 + $1,250,000 - $175,000 - $135,000

=$1,390,000

How much did NBCF report in investments at the end of FY 2020?

= Beginning Balance + Additions – Withdrawals + Unrealized Gain (Loss) + Realized Gain (Loss)

= $14,780,000 + $1,650,000 – $0 + $1,250,000 - $175,000

= $17,505,000

RELIABILITY AND FAIR VALUE ESTIMATES

GAAP (specifically, FASB Statement 157) classifies investments by a three-level scheme according to the availability of market prices. Level 1 assets have a quoted price on a public exchange. This includes stocks of public companies and money market funds, among others. Level 2 assets are primarily sold "over-the-counter," like corporate bonds, futures contracts, stock options, etc. Here the owner must report an estimated price based on prices of comparable assets that have traded recently. Level 3 assets are not bought and sold and therefore do not have a market price. This includes more exotic investments like venture capital funds, hedge funds, and private equity. For Level 2 and Level 3 assets, the owner must discount the reported asset value to account for uncertainty in that valuation.

Public organizations frequently borrow money to finance the purchase of equipment, pay for renovations to property, purchase new property, or cover operating expenses. Loans include lines of credit, notes payable, mortgages, and municipal bonds. A line of credit is an agreement between an organization and a bank that allows that organization to borrow money on short notice at a pre-determined interest rate. A line of credit can be especially useful if an organization has unpredictable cash flows. Notes payable are short-term loans with maturities ranging from 18 months up to 60 months. A mortgage is a loan secured with real estate. Unlike mortgages, municipal bonds and notes are unsecured or secured with pledged revenues, not property. Like mortgages, municipal bonds have a longer maturity of up to 30 years.

Borrowers have to pay interest on the loans at a fixed rate. There are exceptions. Interest rates on lines of credit and some municipal bonds are variable or floating rates (e.g., prime rate + 4.00%).

The initial accounting recognition of a loan is simple. The borrowed money, or loan principal, is recognized as a liability that offsets the cash received from the loan:

Transaction 7: Treehouse borrows $30,000 from a local bank to finance the purchase of a van. The loan is for five years at seven percent annual interest, and interest is paid annually. Treehouse purchased the van immediately after the loan closed.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $30,000 | Loan Payable (current) |

+ $6,000 | ||

| Cash | - $30,000 | Loan Payable (non-current) |

+ $24,000 | ||

| Equipment | + $30,000 | ||||

The purchase of a van results in an increase in a non-current asset (equipment). However, the full loan amount is not a current liability – only the amount due in the next 12 months is reported as a current liability – and the remainder is a non-current liability. As a result, the non-profit is not less liquid, as only the current portion of the loan is considered a current liability. On the asset side, cash remains unaffected, as all the proceeds from the loan were used to purchase the equipment.

Transactions related to repaying debt present some special accounting considerations. Consider the previous example. Treehouse has agreed to pay interest on the loan each year the loan is active. The $30,000 loan principal is a liability; the interest on that loan principal is not. Payment of interest on the loan is an expense. Treehouse will be paying the bank (or lender) for access to credit, which in essence, is a “service.” For that reason:

Transaction 8: Treehouse makes its first annual principal and interest payment on the loan described in Transaction 7.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | - $8,100 | Loan Payable (current) |

- $6,000 | Interest Expense | -$2,100 |

Since the $30,000 loan is paid off annually over five years, the annual payment on the principal is $6,000, or $30,000/five years). The interest rate on the loan is seven percent, so interest expense is equal to $2,100, or $30,000 X 0.07.

In year 2, the current portion of the loan would be $6,000, and the non-current portion would be $18,000. The total loan outstanding would be $24,000 (i.e., $30,000 - $6,000 or $6,000 + $18,000).

Treehouse would pay $7,680 to cover a $6,000 payment on the loan principal and $1,680 of interest expense (i.e., $24,000 X 7%).

If Treehouse did not make its interest payments on time, the expense would be recognized as a liability. The non-profit would also need to recognize as an expense (if paid) or liability (if unpaid) if the lender imposes additional fines or penalties as a result of non-payment.

TRANSACTIONS THAT AFFECT THE INCOME STATEMENT

Treehouse's mission demands that it focus most of its efforts on delivering services. As a result, most of its day-to-day financial activity will involve revenues and expenses. Revenues and expenses affect the income statement.

For instance, recall from the earlier discussion that Treehouse delivers outreach programs at local schools. When one of those programs is delivered, it records revenue.

Transaction 9a: Treehouse delivers an outreach program at a local school and sends that school district an invoice for $2,500.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Accounts Receivable | + $2,500 | Program Revenue | + $2,500 | ||

Here Treehouse has earned revenue because it delivered a program. It recognizes those earned revenues as “program revenue.” Program revenues represent an increase in net assets “without donor restrictions.” Restrictions would apply for public support, including donations, in-kind contributions, and foundation grants—more on this below.

Did it receive a payment? No. We, therefore, need to recognize a receivable on the asset side. The receivable is an accounts receivable since revenue is earned. For donations, the receivable would be pledges receivable; for grants, the receivable would be grants receivable.

Three weeks later, when Treehouse collects payment, it will convert that receivable into cash. That transaction is as follows:

Transaction 10: Treehouse receives payment from the school district for the outreach program delivered three weeks ago.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $2,500 | ||||

| Accounts Receivable | - $2,500 | ||||

Transaction 10 does not affect the income statement but remember that the transaction that resulted in the original accounts receivable did.

Note, if Treehouse had received payment immediately at the end of the session, then:

Transaction 9b: Treehouse delivered an outreach program at a local school and received a payment of $2,500.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $2,500 | Program Revenue (Net Assets, Without Donor Restrictions) |

+ $2,500 | ||

In Transaction 9, Treehouse earned revenue. Of course, that revenue did not just appear. Treehouse incurred various expenses – staff time, travel, supplies, etc. – to deliver that service. When should it recognize the expenses incurred to deliver that program? One of the core principles of GAAP is the matching principle. That is, when we recognize revenue, we should recognize expenses that were incurred to produce that revenue. This is not always clear for services. Services are driven by personnel, and we incur personnel expenses constantly. Services also require equipment, certifications, and other assets where it is not always clear what it means to “use” that asset.

The matching principle is more applicable when the transaction involves a good rather than a service. When an organization sells a good, it presumably knows what it costs to produce that good. Those costs, known generally as the cost of goods sold, are immediately netted against the revenue collected from the transaction. That is why, in the flow chart above, you see some additional recognition related to delivering goods.

That said, public organizations encounter a few typical transactions that account for many of their expenses. First and most important is when Treehouse pays its staff and recognizes salary expenses.

Transaction 11: Treehouse recognizes and pays bi-weekly payroll of $15,000.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Wages Payable | + $15,000 | Wage Expense | - $15,000 | ||

| Cash | - $15,000 | Wages Payable | - $15,000 | ||

Payroll is critical because personnel is the largest expense for most public organizations. From the organization’s perspective, payroll is an expense because it receives services from its employees. That “service” is their day-to-day work. This is different than if the organization hired the one-time services of, say, a plumber from another company to fix some leaky pipes. But the accounting recognition is essentially the same.

Keep in mind that there is frequently a lag between when wage expense is recognized and when payroll is remitted. The first transaction recognizes the expense; the second transaction recognizes payment on an outstanding liability. The initial transaction would be reflected in the income statement; the subsequent transaction would not.

Treehouse incurred other expenses to deliver the school outreach program. The program was held at a school 100 miles from the non-profit’s headquarters. The two staff members who delivered that program rode together to that off-site location in their personal vehicles. They will expect to be reimbursed. Many non-profits and government organizations follow the federal government’s guidance and reimburse mileage at a fixed rate of 57.5 cents per mile.

Transaction 12: Treehouse pays mileage expenses of 57.5 cents/mile for a 100-mile round trip for two staff members.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | - $115 | Mileage Expense | - $115 | ||

To deliver the outreach program, staff used up $100 of construction paper, colored pencils, and other supplies. Recall that supplies are an asset. To account for the full cost of the outreach program, we should also recognize that Treehouse "used up" or "expensed" these assets. For example:

Transaction 13: Treehouse expenses $100 in supplies related to its outreach program.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Supplies | - $100 | Supplies Expense | - $100 | ||

LIFO AND FIFO

Inventory presents some unique challenges for accounting recognition. Organizations use inventory all the time, so most have to estimate the value of inventory assets at any moment. There are several ways to produce those estimates, including First In, First Out (FIFO) , and Last In, First Out (LIFO). For organizations that use a lot of inventory, small changes to inventory valuation can significantly change the reported value of inventory and inventory expense. That said, for most public managers, the technical aspects of inventory valuation fall squarely within the realm of "know what you don't know."

PRACTICE PROBLEM: EARNED INCOME AND EXPENSES

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) operates a gift shop and coffee bar. The gift shop reported $1,425,000 in revenues (all cash sales). Payroll expenses for the year were $650,000. The Museum purchased $325,000 in inventory (for the gift shop) and $145,000 in supplies (for the coffee bar) and reported a balance of $45,000 in inventory and $7,000 in supplies.

Assuming all purchases and expenses had been paid in full, how much did the gift shop report in profits or losses in its gift shop operations for the fiscal year?

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | +$1,425,000 | Program Revenue (Net Assets, Without Donor Restrictions) | +$1,425,000 | ||

| Earned income reported as revenue without donor restrictions. Cash sales increase MCA cash balances. | |||||

| Cash | -$325,000 | ||||

| Inventory | +$325,000 | ||||

| Cash | -$145,000 | ||||

| Supplies | +$145,000 | ||||

| MCA purchased $325,000 in inventory for the gift shop and $145,000 in supplies for its coffee shop operations. Venders were paid in full, upon delivery. | |||||

| Inventory | -$280,000 | Inventory Expense | -$280,000 | ||

| Supplies | -$138,000 | Supplies Expense | -$138,000 | ||

| Of the $325,000 in inventory, MCA reports a balance of $45,000. Assuming there was no inventory at the start of the financial period, inventory expense would be the difference between inventory purchased and balances at the end of the year (i.e., $325,000 - $45,000). The same applies for supplies. Supplies expense is equal to purchased supplies fewer supplies available at the end of the year ($145,000-$7,000). | |||||

| Wages Payable | +$650,000 | Payroll Expense | -$650,000 | ||

| Cash | -$650,000 | Wages Payable | -$650,000 | ||

| Payroll expense of $650,000. Wages payable were paid in full. | |||||

So, how much did MCA report in earned income from the gift shop and coffee bar? To estimate profit, we review transactions in the Net Asset column of the transaction sheet. As discussed in this chapter, all revenues are reported as an increase in net assets, and all expenses are reported as a decrease in net assets. Net income (or Change in Net Assets) is the difference between revenues and expenses.

We estimate the overall profitability was $357,000 (i.e., $1,425,000 - $280,000 - $138,000 - $ 650,000). Net income represents an increase in MCA’s net worth. If you were to estimate the balances in each asset account reported on the right-hand side, you would find the organization’s assets also increased by $357,000.

| Gift Shop Balance Sheet | |

|---|---|

| Assets | |

| Cash* | $305,000 |

| Inventory | $45,000 |

| Supplies | $7,000 |

| Total Assets | $357,000 |

| Liabilities | $0 |

| Net Assets | |

| Without Donor Restrictions | $357,000 |

| With Donor Restrictions | $0 |

| Total Net Assets | $357,000 |

Recall that Treehouse also pre-pays for many of its ongoing expenses, such as insurance and certifications. The choice of when to expense pre-paid items is admittedly arbitrary. Most organizations have accounting policies and assumptions that state when and how this happens. Most will record those expenses monthly or quarterly. Recall that Treehouse pre-paid $1,500 for some annual professional association memberships. Assume that it expenses those memberships quarterly. At the end of the first quarter, since the membership was paid, it would record:

Transaction 14: Treehouse records quarterly professional association membership expenses. Recall that annual association dues are $1,500.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Prepaid Expenses | - $375 | Membership Expense | - $375 | ||

Remember that after this first portion is expensed, $1,125 in pre-paid association membership expenses remains on the balance sheet. In other words, this transaction expenses one-quarter of the original $1,500 asset.

Another crucial set of accounting assumptions is around depreciation. To deliver services, Treehouse must use up some portion of its building, vehicles, audiology equipment, and other capital items. Like with salaries and pre-paid expenses, it’s not always clear when and how those assets are “used up.” Some of that use is normal wear and tear. Some of it might happen if the asset bears a particularly heavy workload. Some capital items might be largely out of use, but they will lose value because, each year that goes by, they’ll become harder for Treehouse to sell should they choose to liquidate them.

Without a detailed way to measure that wear and tear, accountants typically deal with depreciation by simplifying assumptions. One of the most common is to use straight-line depreciation, also known as the straight-line method. Under the straight-line method, when an organization purchases a new capital asset, it determines the length of time it can use that asset to deliver services. This is known as the useful life. The organization must also determine the value of that asset once it is no longer useful for delivering services. This is the salvage value, residual value, or value at write-off. If we subtract the salvage value from the historical cost and divide it by the useful life, we get the annual depreciation expense.

For example, let’s return to Treehouse’s office furniture. Recall that it purchased that furniture for $20,000. Say that equipment has a useful life of 10 years. Also, assume that at the end of its useful life Treehouse will be able to sell it for $2,500. To calculate the annual depreciation expense using the straight-line method, we take the purchase price of $20,000, subtract the salvage value of $2,500, and divide the difference by 10. The estimated depreciation expense would be $1,750 per year. Using this assumption, we could record the following transaction:

Transaction 15: Treehouse records an annual depreciation expense of $1,750 on its equipment.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Equipment | - $1,750 | Depreciation Expense | - $1,750 | ||

After this first recording for depreciation expense, the value of the equipment reflected in the Balance Sheet will be $18,250 (i.e., $20,000 - $1,750). We refer to the value of assets, net of depreciation, as the “book value.”

Other methods of calculating depreciation expense include accelerated method, declining balance, and sum-of-the-years method. Underlying assumptions in each method produce different estimates of depreciation expenses.

PRACTICE PROBLEM: DEPRECIATION

Dorchester Home Health Services (DHHS) is a private, non-profit home health agency. At the start of FY 2020 (i.e., July 1, 2019), DHHS reported $5,900,000 in fixed assets (net of depreciation).

The non-profit sold its existing fleet of vehicles, with a book value of $12,000, for $15,000.

It paid for the new vehicles in cash on October 1, 2019, at a cost of $200,000. Assuming that these vehicles have a useful life of five years and a salvage value of $20,000, how much should DHHS report in fixed assets (net of depreciation) at the end of the year? You may assume DHHS uses the straight-line depreciation method, and the estimated depreciation expense on existing equipment for FY 2020 was $195,000.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | +$15,000 | ||||

| Software License | -$12,000 | Profits from the Disposal of Assets | +$3,000 | ||

| The purchase of four new vehicles at a cost of $200,000, all of which was paid in cash. | |||||

| Cash | -$200,000 | ||||

| Fixed Assets | +$200,000 | ||||

| The purchase of four new vehicles at a cost of $200,000, all of which was paid in cash. | |||||

| Fixed Assets (Depreciation) | -$195,000 | Depreciation Expense | -$195,000 | ||

| Fixed Assets (Depreciation) | -$27,000 | Depreciation Expense | -$27,000 | ||

| Depreciation expense for the new equipment = ($200,000 - $20,000)/five years = $36,000. Note, however, that the vehicles were purchased on October 1, 2019. We therefore need to pro-rate the depreciation expense, as DHHS owned the vehicles for nine months. Pro-rated depreciation expense is $27,000 (i.e., ($36,000/12 months) x nine months). | |||||

Fixed assets, net of depreciation, at the end of FY 2020:

= Beginning Balance + Additions – Eliminations – Deprecation

=$5,900,000 + $200,000 -$12,000 – ($195,000+$27,000)

=$5,866,000

This same concept of spreading out the useful life also applies to intangible assets. Say, for example, Treehouse purchases some specialized case management software that allows it to store client records safely. That software requires Treehouse to purchase a five-year license. That license is an intangible asset, and the non-profit expects to utilize the software over the next five years. In this case, Treehouse would amortize the intangible asset – i.e., recognize that the value of the intangible asset decreases every year. The expense associated with using that intangible asset is referred to as amortization expense. If Treehouse purchased a five-year license for $5,000, it would record a $5,000 software license as an asset at that purchase. After that, if it amortized that license in equal annual installments, the effect on the fundamental equation is as follows:

Transaction 16: Treehouse purchased a records management software for $5,000. Assuming a useful life of five years, the annual amortization expense is estimated to be $1,000.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | - $5,000 | ||||

| Software License | +$5,000 | ||||

| Software License | - $1,000 | Amortization Expense | - $1,000 | ||

Following this first amortization expense, the license would remain on Treehouse's balance sheet at $4,000.

Finally, we must consider what happens if Treehouse is paid for a service before it delivers it. This is known as deferred revenue or unearned revenue. Deferred revenue is a liability because it represents a future claim on Treehouse resources. By taking payment for a service not yet delivered, Treehouse is committing future resources to deliver that service. Once it delivers that service, it incurs expenses and removes that liability.

For example, imagine that Treehouse arranges a $1,500 outreach program with a different school district. That school district is nearing the end of its fiscal year, so it agrees to pay Treehouse for the program several weeks in advance. Once it receives that payment, it would recognize that transaction as follows:

Transaction 17: Treehouse takes a $1,500 payment for a school outreach program to be delivered in the future.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $1,500 | Deferred Revenue | + $1,500 | ||

This initial transaction does not affect the income statement. However, when Treehouse delivers the program a few weeks later, it records the following:

Transaction 18: Treehouse delivers the school outreach program for which it was paid previously.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Deferred Revenue | - $1,500 | Program Revenue (Net Assets, Without Donor Restrictions) |

+ $1,500 | ||

The key takeaway from all these income statement transactions is simple: For Treehouse to be profitable, it must take in more revenue from its programs and services than the total payroll and other expenses it incurs to deliver those programs. If revenues exceed expenses, then its net assets will increase. If expenses exceed revenues, then net assets will decrease. That is why, as previously mentioned, change in net assets is the focal point for much of our analysis of an organization's financial position.

RECOGNITION CONCEPTS FOR SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES

PLEDGES AND DONOR REVENUES

Non-profits aren’t traditionally paid for their services. In fact, large parts of the non-profit sector exist precisely to provide services to those who cannot pay for those services. People experiencing homelessness, foster children, and endangered species come to mind immediately. Non-profits depend on donations and contributions to fund those services.

At the outset, it might seem like the accrual concept breaks down here. How can a non-profit recognize revenue if the recipients of its services do not pay for those services? In non-profit accounting, we address this problem by simply drawing a parallel between donations and payments for service. Donors who support a non-profit are, in effect, paying that non-profit to pursue its mission. Donors may not benefit directly from their contribution, but they benefit indirectly through tax benefits and a feeling of generosity. Those indirect benefits are substantial enough to support the accrual concept in this context.

Practically speaking, we address this with a category of net assets called “donor revenue” and a category of assets called “pledges receivable.” For example:

Transaction 19: Treehouse received pledges of gifts in the amount of $2,500 to be used as its Board of Directors considers appropriate.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Pledges Receivable | + $2,500 | Net Asset without Donor Restrictions (Public Support) |

+ $2,500 | ||

Most donor revenues happen through the two-step process suggested here. A donor pledges to donate which is recognized as pledges receivable. GAAP stipulates that a signed donor card or other documented promise to give constitutes a pledge that can be recognized. Once the donor writes Treehouse a check for the pledged amount, Treehouse will book the following:

Transaction 20: Treehouse collects the $2,500 pledge recognized in Transaction 19.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $2,500 | ||||

| Pledges Receivable | - $2,500 | ||||

NET ASSETS SUBJECT TO DONOR RESTRICTIONS

One of the big financial questions for any non-profit is how much control it has over where its money comes from and where it goes. In a perfect world, non-profit managers fund all their operations through unrestricted program revenues and donations. It is much easier to manage an organization when no strings are attached to its money.

Most non-profit managers aren’t so lucky. Virtually all non-profits have some restrictions on when and how their organization can spend money. Donors who want to ensure the organization accomplishes specific goals will restrict how and when their donation can be spent. Governments do the same with restricted grants or loans. Some resources, namely endowments, can’t ever be spent.

Restricted resources usually appear as “net assets with donor restrictions.” Consider this example:

Transaction 21: Treehouse receives a cash donation of $5,000. That gift was accompanied by a letter from the donor to Treehouse's executive director requesting that the donation be used for staff development.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $5,000 | Net Asset with Donor Restriction (Public Support) |

+ $5,000 | ||

This is a typical revenue subject to donor restrictions. The donor has specified how Treehouse will use these donated resources. We’d see a similar restriction if the donor had specified that the donation could not be spent for some period of time.

Previously, net assets with donor restrictions were reported as either temporarily or permanently restricted net assets. Temporarily restricted net assets were restricted with respect to time or use. Permanently restricted net assets were permanently restricted and could never be spent. Recent changes in financial reporting altered the reporting of restricted gifts and aggregated these two categories, now reported as “Net Assets with Donor Restrictions.” While this change altered the presentation of financial information in the audited financial statements, it did not alter donor intent. In other words, if a donor had provided a gift to be used in perpetuity, the accounting rules do not alter that donor’s intent. They change how we report that information. The focus is now on all assets subject to donor restrictions – irrespective of whether they are time-restricted, use-restricted, or the corpus is restricted in perpetuity.

Our accounting recognition for net asset restrictions is not unlike other transactions that affect the income statement. The main difference is that with restricted net assets, we have to take the additional step of “undoing” the restriction once the donor’s conditions have been satisfied. For instance:

Transaction 22: Treehouse staff attend a national training conference. Travel, lodging, and conference registration expenses were $3,990. Staff are reimbursed from the resources donated in Transaction 21.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Released from Restrictions (From Net Assets with Donor Restrictions) |

- $3,990 | ||||

| Released from Restrictions (To Net Assets without Donor Restrictions) |

+ $3,990 | ||||

| Cash | -$3,990 | Professional Development Expense | - $3,990 | ||

The first part of this transaction converts donations subject to restrictions to unrestricted revenue. This is reported in the income statement as “released from restrictions.” Treehouse can do this conversion because it has met the donor's condition: staff attended a professional development conference. The second part of the transaction recognizes the professional development expenses. Not all expenses are reported under “Net Assets Without Donor Restriction.” No expenses are reported in the “Net Assets with Donor Restrictions” column. Why? All expenses originate within the organization and, therefore, cannot be restricted by an external third party. Revenues, on the other hand, are resources provided to the organization and therefore, can be restricted. After the transaction, $1,010 of the original gift remains in Treehouse's balance sheet and income statement as “Net Assets with Donor Restriction.”

While we often think of restricted gifts as contributions, restricted gifts do include property and equipment. Following FASB’s Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2016-14, assets should be released from donor restrictions when they are placed in service rather than releasing donor restrictions over estimated useful life (unless otherwise stipulated by the donor). In other words, if the gift of a vehicle or building is being used as intended by the donor, that asset is reported under “Net Assets without Donor Restriction.”

Net assets restricted in perpetuity (previously classified as permanently restricted net assets) most often appear as endowment investments. Endowment investments represent a pool of resources that exists to generate other assets to support the organization's mission. By definition, the donation that comprises the original endowment – also known as the corpus – cannot be spent. In practice, the accounting recognition for the formation of an endowment looks like this:

Transaction 23: An anonymous benefactor donates 3,500 shares of Vanguard's Global Equity Investor Fund (a mutual fund) to Treehouse. The gift stipulates that the annual investment proceeds from that stock support general operations and that Treehouse cannot, under any circumstance, liquidate the endowment. At the time of the gift, the investment had a fair market value of $100,000.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Investments | + $100,000 | Net Asset with Donor Restriction (Public Support) |

+ $100,000 | ||

Once the endowment is established, it generates investment earnings that are not subject to donor restrictions unless otherwise stipulated by the donor. Income from endowment investments is recorded as “distribution from endowment” or “endowment investment income.”

Transaction 24: At the end of the Endowment's first fiscal year, Treehouse receives a dividend check from Vanguard (the mutual fund manager) for $4,500.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $4,500 | Net Asset without Donor Restriction (Investment Income) |

+ $4,500 | ||

If the anonymous benefactor designated the income from the mutual fund to be used for a specific program or activity, the investment income would be reported under “Net Asset with Restriction.”

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash (With Restrictions) |

+ $4,500 | Net Asset with Donor Restriction (Investment Income) |

+ $4,500 | ||

Remember, not all investments are endowment investments. The non-profit could report an investment portfolio significantly larger than its endowment, especially if income from the endowment exceeds distributions or the non-profit has diverted excess cash to investments over time. While unrestricted investments are reported together with restricted investments, restricted investments remain subject to donor restrictions.

Even though the format of the financial statements – Net Assets without Restrictions and Net Assets with Restrictions – simplifies the presentation of financial information, non-profits must report in detail about the nature and purpose of Net Assets with Donor Restrictions.

PRACTICE PROBLEM: PUBLIC SUPPORT WITH DONOR RESTRICTIONS

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) receives a $1,000,000 cash gift from Mr. and Mrs. Carter. The donors have asked the museum to create an endowment for $750,000 and use all other funds to curate a collection of contemporary music. The donors expect the MCA to create a contemporary music collection in the summer of 2022.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash (With Restrictions) | +$1,000,000 | Net Asset with Donor Restriction (Public Support) | +$250,000 | ||

| Net Asset with Donor Restriction (Public Support) | +$750,000 | ||||

| The cash gift is subject to donor restrictions. We therefore record receipt of donation and an increase in net assets “with donor restrictions.” Note, that we separate out the funds that can be expended in the near term, having met donor requirements from those that cannot be expended. Recent changes in accounting rules eliminated previous categories – temporarily restricted versus permanently restricted. That said, the accounting rules only apply to reporting. The reporting requirement does not eliminate donor intent. The non-profit has to maintain accounting records that accommodate donor intent. In this instance, the $750,000 can never be expended, whereas the $250,000 would be expended at a future date for purposes designated by the donor. | |||||

| Cash (With Restrictions) | - $750,000 | ||||

| Investments (With Restriction) | +$750,000 | ||||

| MCA transferred funds from Cash to Investments. Note, that while the gift of $750,000 is restricted, income from the gift is not restricted, unless the donor has imposed that restriction. | |||||

IN-KIND CONTRIBUTIONS

In addition to donated revenue, non-profits also depend on donations of goods and services. These are called in-kind contributions. According to GAAP, a non-profit can record as an in-kind contribution to specialized services that it would otherwise purchase. This usually means professional services like attorneys, counselors, accountants, or professional development coaches. We recognize in-kind services once they’ve been received, and all the recognition happens in the net assets part of the fundamental equation. For instance:

Transaction 25: A local attorney agrees to represent Treehouse "pro bono" in a lawsuit filed by the family of a former client. The attorney's regular rate is $500/hour, and the case requires ten billable hours. Without these pro bono services, Treehouse would have had to hire outside counsel.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Net Asset without Donor Restriction (In-Kind Public Support) |

+ $5,000 | ||||

| Attorney Fees | - $5,000 | ||||

If in-kind contributions don’t result in a net increase or decrease in net assets, then why do we bother recognizing them? Because recognizing them helps us understand the organization's capacity to deliver its services. If it had to pay for otherwise donated goods and services, those purchases would undoubtedly affect its financial position and its service-delivery capacity.

Some in-kind contributions produce both an in-kind contribution and a donated asset. This is especially important for services like carpentry or plumbing. For example:

Transaction 26: A local contractor agrees to donate the labor and materials to construct a new playground at Treehouse. Total labor expenses for the project were $3,000, and the contractor purchased the new playground equipment for $8,000.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Net Asset without Donor Restriction (In-Kind Public Support) |

+ $3,000 | ||||

| Contractor Fees | - $3,000 | ||||

| Equipment | + $8,000 | Net Asset Without Donor Restrictions (In-Kind Public Support) |

+ $8,000 | ||

The contractor’s donated labor is reported as a revenue and an expense, whereas the donated equipment is reported as an asset and revenue. The asset would then be depreciated over its useful life.

BAD DEBT

Unfortunately, pledges do not always materialize into contributions. Sometimes the donors’ financial situation changes after making a pledge. Sometimes they have too much wine at a gala event and promise more than they can give. Sometimes they change their mind. For these and many other reasons, non-profits rarely collect 100 percent of their pledged revenues.

Most non-profits re-evaluate at regular intervals – usually quarterly or semi-annually – the likelihood they’ll collect their pledges receivable. Once they determine that a pledge cannot or will not be collected, the amount of pledges receivable must be adjusted accordingly. The accounting mechanism to make this happen is an expense called “bad debt.” Bad debt is a specific type of reconciliation entry known as a contra-account. Like with depreciation, amortization, and other reconciliations, contra-account entries do not affect cash flows. They are “write-off” transactions to offset the reduction of an asset, in this case, pledges receivable. Consider this example:

Transaction 27: Treehouse determines it will not be able to collect $3,000 of pledges made earlier in the fiscal year.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Pledges Receivable | - $3,000 | Bad Debt Expense | - $3,000 | ||

When is a pledge deemed uncollectable? That depends on the organization's policies. GAAP rules only state that an organization must have a policy that dictates how it will determine collectability. To that effect, non-profit policies state that a pledge is uncollectable after a certain number of days past the close of the fiscal year or if the donor provides documentation that the pledge is canceled.

Among non-profits, pledges receivable is the most common type of asset to be offset by bad debt expense. However, be aware that bad debt is not unique to non-profits or pledges receivable. For-profits and governments can and often do record bad debt expenses. Those expenses can apply to any receivable, including accounts receivable for goods and services previously delivered or grants receivable from a donor or a government.

MINI CASE: SEATTLE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION

The Seattle Community Foundation (herein referred to as “Foundation”), a non-profit entity that supports charitable organizations in the Puget Sound area, reported the following transactions for FY 2020 (July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020). Use this information to prepare a Statement of Activities.

- The Foundation has a large portfolio of investments. At the beginning of the year, the fair value of the portfolio was $76,850,000. In a 12-month period, the Foundation transferred $4,250,000 from cash to investments.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | - $4,250,000 | ||||

| Investments | + $4,250,000 | ||||

- For the year ending June 30, 2020, the Foundation received $650,000 in interest and dividend payments. Investment managers reported $675,000 in realized gains and $215,000 in unrealized losses. The Foundation reports all investment income (interest and dividend payments, realized gains or losses, and unrealized gains or losses) as revenue without donor restrictions.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | + $650,000 | Net Asset without Donor Restriction (Investment Income) |

+ $650,000 | ||

| Investments | + $675,000 | Net Asset without Donor Restriction (Realized Gains on Investments) |

+ $675,000 | ||

| Realized gains from investments are reported under investments – not cash – if the investments were sold and the investment manager immediately purchased alternative investments. If investments were sold and proceeds were transferred to cash, a secondary transaction would be reported here. For simplicity, we assume that the non-profit did not transfer funds from investments to cash. | |||||

| Investments | - $215,000 | Net Asset Without Donor Restriction (Unrealized Loss on Investments) |

- $215,000 | ||

- The Foundation held its annual fundraising dinner event on February 18, 2020. The dinner raised $1,600,000 in unrestricted support and $3,200,000 in restricted support.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Pledges Receivable (Without Donor Restriction) |

+ $1,600,000 | Net Asset without Donor Restriction (Public Support) |

+ $1,600,000 | ||

| Pledges Receivable (Without Donor Restriction) |

+ $3,200,000 | Net Asset with Donor Restriction (Public Support) |

+ $3,200,000 | ||

| Public support with donor restrictions is reported separately from public support without donor restrictions on both the asset side (as pledges receivable) and on the net asset column (as public support or revenue). See the Statement of Activities below. | |||||

- As of June 30, 2020, the Foundation had received $825,000 of the $1,600,000 in unrestricted support and $1,250,000 of the $3,200,000 in restricted support. Historically, 1.5 percent of all pledges have been uncollectable.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Pledges Receivable (Without Restrictions) |

- $825,000 | ||||

| Cash (Without Restrictions) |

+ $825,000 | ||||

| Pledges Receivable (With Restriction) |

- $1,250,000 | ||||

| Cash (With Restriction) |

+ $1,250,000 | ||||

| Pledges Receivable (With Restrictions) |

- $48,000 | Bad Debt Expenses | - $72,000 | ||

| Pledges Receivable (Without Restrictions) |

- $24,000 | ||||

| Even though the Foundation received payment on a portion of the pledges subject to donor restriction, receipt of payment does not eliminate the donor restriction. We therefore report the funds separately as cash balances without restrictions and cash balances with restrictions. See transaction 5 below. | |||||

The Foundation’s expenses were as follows:

- The Foundation made $2,100,000 in cash awards to various charitable organizations. Of the total, $1,250,000 was funded with restricted public support. The remainder was funded with unrestricted revenues.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Released from Restrictions (From Net Assets with Donor Restrictions) |

- $1,250,000 | ||||

| Released from Restrictions (To Net Assets without Donor Restrictions) |

+$1,250,000 | ||||

| Cash | - $2,100,000 | Grant Expense | - $2,100,000 | ||

| Public support has to be released from restrictions before it can be expended. Note all expenses are reported in the column “Without Donor Restrictions.” See the Statement of Activities below. | |||||

- Foundation salaries and benefits were $420,000 for the year. Of the total, $35,000 remained unpaid at the end of the year. Fundraising and marketing costs for the year were $150,000. All fundraising and marketing expenses had been paid in full by year-end. Other expenses paid in full included rent and utilities ($144,000), equipment lease ($12,000), office supplies ($8,500), and miscellaneous expenses ($15,000).

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Wages Payable | + $420,000 | Wage Expense | - $420,000 | ||

| Cash | - $385,000 | Wages Payable | - $385,000 | ||

| Cash | - $150,000 | Marketing Expense | - $150,000 | ||

| Cash | - $144,000 | Rent Expense | - $144,000 | ||

| Cash | - $12,000 | Lease Expense | - $12,000 | ||

| Cash | - $8,500 | Supplies Expense | - $8,500 | ||

| Cash | - $15,000 | Miscellaneous Expenses | - $15,000 | ||

- On June 28th, the investment manager sent the Foundation an invoice for services rendered in FY 2020 for $82,000. The Foundation expected to write a check for the full amount on July 15, 2020.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Accounts Payable | + $82,000 | Investment Manager Fee | - $82,000 | ||

- The Foundation purchased $21,000 in computing equipment in cash. The new equipment is expected to have a useful life of three years and zero salvage value. Depreciation expenses on existing equipment for FY 2020 were expected to be $32,500.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Fixed Assets | + $21,000 | ||||

| Cash | - $21,000 | ||||

| Fixed Assets | - $7,000 | Depreciation Expense | - $7,000 | ||

| Fixed Assets | - $32,500 | Depreciation Expense | - $32,500 | ||

| Depreciation expense for the new equipment = ($21,000 - $0)/three years = $7,000. | |||||

- For FY 2020, the Foundation reported $25,000 in interest expense on its long-term debt. The Foundation had also made $75,000 in principal payments for the year.

| Assets | = Liabilities | + Net Assets | |||

| Cash | - $100,000 | Loan Payable | - $75,000 | Interest Expense | - $25,000 |

SEATTLE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

STATEMENT OF ACTIVITIES FOR THE YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2020 |

||||

| Revenues | Without Donor Restrictions | With Donor Restrictions | Total | |

| Public Support | ||||

| Donor Revenue | $1,600,00 | $3,200,000 | $,8000,000 | |

| Net Assets Released from Restrictions | $1,250,000 | ($1,250,000) | - | |

| Earned Income | ||||

| Investment Income | $650,000 | $650,000 | ||

| Realized Gains | $675,000 | $675,000 | ||

| Unrealized Gains | ($215,000 | ($215,000) | ||

| Total Revenues | $3,960,000 | $1,950,000 | $5,910,000 | |

| Expenses | ||||

| Grant Expense | $2,100,000 | $2,100,000 | ||

| Bad Debt Expense | $72,000 | $72,000 | ||

| Wage Expense | $420,000 | $420,000 | ||

| Fundraising Expense | $150,000 | $150,000 | ||

| Rent and Utilities | $144,000 | $144,000 | ||

| Equipment Lease | $12,000 | $12,000 | ||

| Supplies Expense | $8,500 | $8,500 | ||

| Miscellaneous Expense | $15,000 | $15,000 | ||

| Investment Manager Fee | $82,000 | $82,000 | ||

| Depreciation Expense | $39,5000 | $39,5000 | ||

| Interest Expense | $25,000 | $25,000 | ||

| Total Expenses | $3,068,000 | $3,068,000 | ||

| Change in Net Assets | $892,000 | $1,950,000 | $2,842,000 | |

How much did the Foundation report as Investments on June 30, 2020?

= Beginning Balance + Additions – Withdrawals + Unrealized Gain (Loss) + Realized Gain (Loss)

= $76,850,000 + $4,250,000 + $675,000 – $215,000

= $81,560,000

(Note: Investment income of $650,000 was reported under Cash, not Investments, so it is not included in the balance here)

How much was reported as pledges receivable on June 30, 2020?

=Public Support – Payment Received – Bad Debt Expense

=$4,800,000 - $825,000 - $1,250,000 - $24,000 - $48,000

=$2,653,000

DEBITS AND CREDITS

You've probably heard accountants talk about debits and credits. They are the basis for a system of accounting shorthand. In this system, every transaction has a debit and a credit.

A debit increases an asset, decreases a liability, or decreases net assets. Debits are always on the left of the account entry. A credit decreases an asset account, increases a liability, or increases net assets. Credits are always on the right of the account entry.

Debits and credits must always balance.

To illustrate, let's say Treehouse delivers a service for $1,000 and is paid in cash. Here, we would debit cash and credit services revenue. That entry is as follows:

| Debit | Credit | |

| Cash | $1,000 | |

| Revenue (Net Assets, without Donor Restrictions) | $1,000 |

For another illustration, imagine that Treehouse receives $500 cash in payment of an account receivable. That entry is:

| Debit | Credit | |

| Cash | $500 | |

| Accounts Receivable | $500 |

If Treehouse purchased $750 of supplies on credit, we would debit supplies and credit accounts payable:

| Debit | Credit | |

| Supplies | $750 | |

| Accounts Payable | $750 |

This system is popular because it's fast, easy to present, and appeals to our desire for symmetry. However, it also assumes you're familiar with the fundamental equation and how different types of transactions affect it. If you're new to accounting, this can be a big conceptual leap. That's why throughout this text, we present transactions relative to the fundamental equation of accounting rather than as debits and credits. We encourage you to try out debits and credits as you work the practice problems throughout this text.

MINI CASE CONTINUED, DEBITS AND CREDITS: SEATTLE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION

- The Foundation has a large portfolio of investments. At the beginning of the year, the fair value of the portfolio was $76,850,000. In the 12-month period, the Foundation transferred $4,250,000 from cash to investments.

| Debit | Credit | |

| Investments | $4,250,000 | |

| Cash | $4,250,000 |

- For the year ending June 30, 2020, the Foundation received $650,000 in interest and dividend payments. Investment managers reported $675,000 in realized gains and $215,000 in unrealized losses. The Foundation reports all investment income (interest and dividend payments, realized gains or losses, and unrealized gains or losses) as revenue without donor restrictions.

| Debit | Credit | |

| Cash | $650,000 | |

| Net Asset Without Donor Restriction (Investment Income) | $650,000 | |

| Investments | $675,000 | |

| Net Asset Without Donor Restriction (Realized Gains on Investments) | $675,000 | |

| Net Asset Without Donor Restriction (Unrealized Loss on Investments) | $215,000 | |

| Investments | $215,000 |

- The Foundation held its annual fundraising dinner event on February 18, 2020. The dinner raised $1,600,000 in unrestricted support and $3,200,000 in restricted support.

| Debit | Credit | |

| Pledges Receivable | $1,600,000 | |

| Net Asset Without Donor Restriction (Public Support) | $1,600,000 | |

| Pledges Receivable | $3,200,000 | |

| Net Asset With Donor Restriction (Public Support) | $3,200 |

- As of June 30, 2020, the Foundation had received $825,000 of the $1,600,000 in unrestricted support and $1,250,000 of the $3,200,000 in restricted support. Historically, 1.5 percent of all pledges have been uncollectable.

| Debit | Credit | |

| Cash (Without Restrictions) | $825,000 | |

| Cash (With Restrictions) | $1,250,000 | |

| Pledges Receivable | $2,075,000 | |

| Bad Debt Expense | $72,000 | |

| Pledges Receivable | $72,000 |

The Foundation’s expenses were as follows:

- The Foundation made $2,100,000 in cash awards to various charitable organizations. Of the total, $1,250,000 was funded with restricted public support. The remainder were funded with unrestricted revenues.

| Debit | Credit | |

| Released from Restriction (From Net Assets with Donor Restrictions) | $1,250,000 | |

| Released from Restrictions (To Net Assets without Donor Restrictions) | $1,250,000 | |

| Grant Expense | $2,100,000 | |

| Cash | $2,100,000 |