5 Cost Analysis

COST ANALYSIS: WHAT DOES THIS COST?

Cost analysis is useful for addressing several key questions that managers ask:

- Will the revenue from a new grant opportunity cover the costs of expanding a program?

- Will a program or service benefit from economies of scale? If not, why not?

- How much should we budget for a new staff member? To add a new shift or another group of new staff?

- How much “overhead” or “indirect costs” should we negotiate into a contract with a government?

- What price should we set for a new fee-based service?

- When will we need to add more staff, and how will adding staff affect our cost structure?

- What’s the best way to share costs between departments within an organization? Between organizations? Between units of government?

In February 2016, a federal judge in Albuquerque, NM, approved a $1 billion settlement between the Obama administration and nearly 700 Native American tribes. This settlement ended a decades-long class action lawsuit over how the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) had distributed aid to tribes since the mid-1970s.

This case came about because of some disagreements over how to measure costs. For over 150 years, the BIA was directly responsible for most of the health care, education, economic development, and other core services delivered on Native American reservations. But then, starting in the mid-1970s, it shifted its focus from direct service provision to helping tribes become self-sufficient. Instead of managing services, it redirected its resources toward training, technical assistance, and other efforts to help tribes launch and maintain their own services.

To make that transition, BIA re-classified many of its activities as “contract support costs.” This change was not just semantic. Funding for direct BIA-administered services is part of a regular federal budget appropriation. That appropriation was stable and predictable. By contrast, funding for support costs on federal government contracts is variable and is often subject to renegotiation. Perhaps not surprisingly, BIA spending declined steadily under this new capacity-building model.

Tribes across the US argued that by re-classifying many of BIA’s costs, the federal government gave itself permission to slash BIA’s budget without Congressional approval. The tribes alleged that this simple cost measurement maneuver allowed BIA to operate well outside its authority and inflict substantial harm on Native Americans around the country. BIA argued that the cost reclassification was a standard accounting change that had been happening across the federal government for decades. The case was ultimately settled for far less than the tribes requested. Still, the federal government did agree to re-classify contract support costs as direct service costs, for which federal funding is far more transparent and predictable.

This case illustrates the central point of this chapter. How we define and measure costs matters tremendously. In this instance, cost measurement is not just a technical exercise; it had real impacts on the lives of hundreds of thousands of Native Americans. The same is true for virtually all public services. How we define, measure, and plan for costs affects which services we deliver and how we deliver them.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define the cost objective and relevant range for the goods and services that public organizations deliver.

- Contrast fixed costs with variable costs.

- Contrast direct costs with indirect costs.

- Allocate costs across departments, organizations, and jurisdictions.

- Determine the full (or total) cost of a good or service.

- Prepare a flexible budget for a program or service.

- Calculate the break-even price and break-even quantity for a good or service.

- Contrast cost-based pricing with price-based costing.

- Recommend management strategies and policies informed by analysis of costs “at the margin.”

- Analyze budget variances, both positive and negative.

What is Cost Analysis?

If you’ve ever flown on an airplane, there’s a good chance you know Boeing. The Boeing Company generates around $90 billion each year from selling thousands of airplanes to commercial and military customers around the world. It employs around 200,000 people, and it’s indirectly responsible for more than a million jobs through its suppliers, contractors, regulators, and others. Its main assembly line in Everett, WA, is housed in the largest building in the world, a colossal facility that covers nearly a half-trillion cubic feet. Boeing is, simply put, a massive enterprise.

And yet, Boeing’s managers know the exact cost of everything the company uses to produce its airplanes, every propeller, flap, seat belt, welder, computer programmer, and so forth. Moreover, they know how those costs would change if they produced more or fewer airplanes. They also know the price at which they sold that plane and the profit the company made on that sale. Boeing’s executives expect their managers to know this information in real time if the company is to remain profitable.

Cost accounting (also known as managerial accounting) is the process of creating information about costs to inform management decisions.

Managers need good information about costs to set prices, determine how much of a good or service to deliver, and manage costs in ways that make their organization more likely to achieve its mission. Managers in for-profit entities like Boeing have instant access to sophisticated cost information that would assist with those types of decisions. But managers in the public and non-profit sectors usually don’t. There are many reasons for this:

- Large parts of the public sector do not produce a “product,” but they deliver services like counseling juvenile offenders, protecting the environment, or housing people experiencing homelessness. Sometimes, we know the “unit” of production and can measure costs relative to that unit. In the case of counseling juvenile offenders, we might think about the cost per offender to provide those services. But for services without a clear “end user,” like environmental protection, this analysis is much more difficult.

- Most (usually around 80 percent) of the costs incurred by a typical public sector organization are related to people. A parole officer will see many different types of parolees. Some will demand a lot of attention and follow-up. Some will need next to none. Some parole officers are comfortable giving each case equal time and attention. Others are not. This type of variability in how and where people spend their time, and as a result, where labor costs are incurred, can make cost analysis quite difficult.

- Employees often work across multiple programs. A program manager at a non-profit organization might work across two programs funded by two different grants from two funding agencies. Unless that program manager allocates their time exactly equally across both programs – and that’s unlikely – we can’t know the exact cost of each program without a careful study of how and where that employee spends their time.

- Public services often share buildings, equipment, vehicles, and other costs. It isn’t easy to know the full cost of services without a system to track which staff and programs use exactly which resources.

- Good cost analysis has no natural political constituency. Careful cost analysis requires substantial investments in information technology, staff capacity, accounting information systems, and other resources. Most taxpayers and funders would rather see that money is spent on programs and services to help people in the short term rather than on information systems to analyze and plan for future costs.

These are just a few of the many barriers that prevent public organizations from acting more like Boeing, at least with respect to cost analysis.

And yet, good cost analysis is critical to public organizations. Public financial resources are finite, scarce, and becoming scarcer. Public managers must understand how and where they incur costs, how those costs will differ under different service delivery models, and whether that pattern of costs is consistent with their organization’s mission and objective. In this chapter, we introduce the core concepts of cost accounting and show how to apply those concepts to real management decisions.

At the outset, it is essential to distinguish between full-cost accounting and differential-cost accounting. Full cost accounting is the process of identifying the full cost of a good or service. Differential cost accounting – sometimes called marginal cost analysis – is the process of determining how the full cost of a good or service changes when we deliver more or less of it. Sound financial management requires careful attention to both.

Let us start with a simple example. Imagine a copying machine that is shared among three departments within the Environmental Health Department of a county government. Those three departments are:

- Food Protection. This includes inspection and licensing of restaurants and other establishments that serve food. This program is designed to prevent outbreaks of food-borne diseases like E. coli, botulism, and Hepatitis A. Staff in this division make around 500 copies each day, mostly related to documenting restaurant inspections.

- Animals and Pests. This includes animal control, rodent testing and control, and educational programs to promote pet safety and neutering/spaying. These programs are designed to prevent communicable diseases, including rabies, that vagrant animals most often spread. Staff in this division make around 250 copies each day, but that number can increase in the event of an outbreak of avian flu or other communicable disease.

- Wastewater. The Wastewater Department is responsible for treating wastewater. Staff in this division issue water discharge permits to businesses and industrial operations and test water quality near wastewater discharge sites. These programs are necessary to prevent waterborne communicable diseases like cryptosporidium. Wastewater staff typically make around 100 copies daily but make up to 1,000 per day when processing complex industrial building permits. They process around six such permits each year.

As a manager, you would want to know what it costs to operate the copier and how those costs should be spread across the three departments. To put this question in the language of cost accounting, we want to know:

- What is the full cost of operating the copier?

- How should we allocate the costs of operating the copier across the three departments?

To answer these questions, we first need to know all of the different ways the copier incurs costs. A few come to mind immediately: paper and toner to make the copies, a lease or rental payment to take possession of the copier, and the occasional maintenance and repairs. A few might be less obvious: electricity to run the machine, space within a building to house the copier, and an office manager’s time to coordinate maintenance and repairs. We can observe many of these costs, but we’ll need to estimate or impute others.

COST VS. PRICE

It’s important at the outset to distinguish between cost and price. Cost is what you give up. Costs include money, time, uncertainty, and, most importantly, the opportunity to invest time or money in another project. In public financial management, we usually talk about cost in terms of the measurable, direct, and indirect financial expenses required to produce or acquire a good or service. Price is the market rate, or “sticker price,” of a good or service.

Most public services are delivered “at cost,” meaning they are priced to generate enough revenue to cover the full cost to deliver them, but not more. The late management guru Peter Drucker called this cost-based pricing. By contrast, many for-profit goods and services are sold at prices well in excess of cost. For instance, most wines are priced at 100-200% above the full cost to produce them. A box of popcorn at the movies is usually priced at 700-800% above cost. And so forth. Wine retailers and cinemas will sell these products at whatever price consumers are willing to pay, regardless of what they cost to produce. Drucker called this price-based costing. Virtually all highly profitable businesses design the cost structure of their products and services around what consumers will pay. The opposite is also true. For-profits often sell goods and services at prices well below cost – a so-called “loss leader” – to attract customers. Most public organizations cannot engage in price-based costing tactics and expect to accomplish their missions and remain financially sound.

The next question is how the departments should share these costs. Imagine, for instance, that they split those costs one-third for each department. This approach is simple, easy, and transparent. But what’s wrong with it? Each department makes a different number of copies, and each has a different workflow related to the copier. These departments also have different potential “economies of scale” for copying. Also, keep in mind that the Animals and Pests department will need “emergency” or “surge” capacity while the other two departments may not. So, if an even distribution is not the most appropriate, what is? With careful attention to cost accounting methods, we can begin to address these and other questions.

Full Cost Accounting

Measuring Full Cost: The Six-Step Method

To answer the question “what does this service cost?” cost accountants follow a six-step process. Each step of this process is driven by policies and procedures that are defined by an organization’s management:

To answer the question “what does this service cost?” cost accountants follow a six-step process. Each step of this process is driven by policies and procedures defined by an organization’s management.

- Define the cost object. The cost object is the product or deliverable for which costs are measured. Service-oriented public organizations typically define cost objects in terms of the end user or recipient of a service. Examples include the cost to shelter a person experiencing housing insecurity for an evening, the cost per counseling session delivered to recovering substance abusers, the cost to place a family in affordable housing, and so forth.

- Determine cost centers. A cost center is a part of an organization that incurs costs. It could be a program, a unit within a department, a department, a grant, a contract, or any other entity defined for cost accounting purposes. Generally, cost centers work best for homogeneous groupings of activities.

- Distinguish between direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are connected to a specific cost center. In fact, they are often called “traceable costs.” Examples include salaries for staff who work entirely within a cost center, facilities and supplies used only by that cost center, training for cost center-specific staff, etc. Many public organizations further stipulate that a cost is direct to a cost center only if that center’s management can control it. Indirect costs apply to more than one cost center. They include shared facilities, general administration, payroll processing services, and information technology support. Some managers call them service center costs, internal service costs, or overhead costs because they are usually for support services provided within an organization.

- Choose allocation bases for indirect costs. One of the main goals of full-cost accounting is to distribute indirect costs to cost centers. This follows from the logic that all direct costs require support from within the organization. An allocation basis is an observable metric we can use to measure the relationship between direct and indirect costs within a cost center. For example, a non-profit might allocate indirect costs according to the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees within a cost center or the percentage of the organization’s overall payroll earned by employees within that cost center. The full cost of any service is the sum of direct costs plus the unit’s share of indirect costs.

- Select an allocation method. There are two main methods to allocate or apportion indirect costs to cost centers. One simply calls indirect costs their own cost centers and plans accordingly. For instance, a non-profit could choose to call the executive director its own cost center. In that case, it would plan for and report the executive director’s salary, benefits, and other costs as a stand-alone entity rather than allocate those costs as an indirect cost to other direct service cost centers. A more common approach is to allocate by a denominator that is common to all the cost centers that incur a particular indirect cost (see below).

- Attach costs to cost objects. One of the biggest challenges for public organizations is that cost objects are usually people, and no two people are alike. For instance, a parole officer might have 30 clients, but each requires a different amount of time, attention, and counseling. When the cost per client varies a lot, the cost accounting system should reflect those differences, usually by applying different overhead rates or percentages to different types of clients.

Let’s illustrate some of these concepts with the copier example. To begin, assume that the copier is a cost center. Services like copying, information technology, and payroll exist to serve clients within the organization, so they are called service centers. One of the goals of cost accounting is to allocate service center costs to mission centers that are more directly connected to the organization’s core programs and services. In this case, we can assume Food Inspection, Animals and Pests, and Wastewater are mission centers that will ultimately receive costs allocated from the copier service center. Given those assumptions about cost centers, we can assume the cost object for the copier service center is the cost per copy.

With those assumptions established, we can define direct and indirect costs for the copier service center. Direct costs include paper, toner, rental/lease fees for the copier, and machine maintenance. These costs are incurred exclusively by the copier. Electricity, building space, and the office manager’s time are indirect costs. They are incurred by the copier cost center and by other cost centers.

To illustrate, the table below lists some details on the copier’s costs.

ANNUAL FULL COST OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH DEPARTMENT COPIER COST CENTER |

|||

DIRECT COSTS |

|||

Cost item |

Number |

Unit Cost |

Total |

Paper |

500 reams | $20/ream | $10,000 |

Toner |

30 cartridges | $90/cartridge | $2,700 |

Machine Rental |

$500/month | 12 months | $6,000 |

Machine Maintenance |

$75/month | 12 months | $900 |

Total Direct Costs |

$19,900 |

||

INDIRECT COSTS |

|||

Cost Item |

Cost Driver / Amount |

Unit Cost |

Total |

Electricity |

1,500 kWh | .12/kWh | $180 |

Building Space |

100 sq. ft. | $15/sq. ft. | $1,500 |

Office Manager Time |

5 hours | $20/hour | $100 |

Total Indirect Costs |

$1,780 |

||

Full Cost |

$21,380 |

||

THE GAP IN COST ACCOUNTING STANDARDS

Keep in mind that there are no national or international standards for how public organizations measure and define their cost structures, also known as their cost accounting practices. Governments employ a variety of state- and local-specific cost accounting methods. Non-profits tend to follow the cost accounting conventions prescribed by federal and state grants or major foundations, but those conventions do not equate to national standards. By contrast, financial accounting – or accounting designed to report financial results to outside stakeholders – is dictated by GAAP. That’s why it’s possible to compare a government’s financial statements to that of another government and a non-profit’s financial statements to that of another non-profit, but not necessarily possible to compare different organizations’ budgets or internal cost accounting systems.

INDIRECT COST ALLOCATION: COST DRIVERS AND ALLOCATION BASES

To find the full cost of the copier cost center, we’ll need to find some way to allocate its share of indirect costs to it. A good cost allocation scheme follows from a clear understanding of an organization’s cost drivers. A cost driver is a factor that affects the cost of an activity. A good cost driver is a reliably observable quantity that shares a consistent relationship with the indirect cost in question. Fortunately, we have an intuitive cost driver for the copier cost center: the number of copies.

Ideally, we can allocate indirect costs according to their key cost driver(s). An allocation basis is a cost driver common to all the cost centers that incur an indirect cost. For building space, for example, we might find the portion of the total building space that is occupied by the copier and allocate a proportionate share of the building space costs to the copier copy center.

For example, this county government allocates electricity costs to different cost centers per kilowatt hour (kWh). Sometimes it is feasible to measure electricity use with this level of precision, and sometimes it is not. Assume that the copier has an individualized meter measuring its electricity use.

This government allocates building space costs per square foot. This assumes it has a reasonably sophisticated way to measure how much space each cost center uses. Allocations by space can be contentious because not every unit uses space in quite the same way to accomplish its mission. For instance, most Food Protection staff spend most of their time in the field inspecting restaurants. They report to the office at the beginning and end of the day but infrequently during the day. This is quite different from the Animals and Pets center, where most of the staff spend most of their time in the office.

These figures also assume that the government allocates the office manager’s time to individual cost centers. The office manager can do this if they track the amount of time they spend on work related to each cost center. Some public organizations have systems, often based on a billable hours concept, similar to those used by professionals like lawyers or accountants. Many do not.

MORE ON COST DRIVERS

One of the big challenges in cost accounting is identifying appropriate cost drivers and allocation bases. Each indirect cost item is a bit different and requires a slightly different concept to support an allocation basis. In fact, many public organizations do not allocate indirect costs precisely because they cannot agree on allocation bases that make sense across an entire organization. That said, many of the most common indirect costs can be allocated using simple metrics that can be computed with existing administrative data.

Here are a few examples:

COST ITEM |

POTENTIAL COST DRIVE/ALLOCATION BASIC |

Accounting |

Number of transactions processed |

Auditing |

Direct audit hours |

Data Processing |

System usage |

Depreciation |

Hours that equipment is used |

Insurance |

Dollar value of insurance premiums |

Legal Services |

Direct hours/Billable hours |

|

|

Number of documents handled |

Motor Pool |

Miles driven and/or days used |

Office Machines |

Square feet of office space occupied |

Management |

Number of employees/total payroll |

Procurement |

Number of transactions processed |

Also, note that the copier cost center does not receive overhead from other service centers. We don’t see, for example, that the copier center is allocated a portion of the county administrator’s salary, insurance expenses, or other organization-wide indirect costs. This is a policy choice. Some public organizations do not require service centers to receive overhead costs, mostly to keep down the rates they must charge their internal clients. Many state and local governments have budgeting rules that state programs – if independently financed or paid for with specific fees or charges rather than general fund resources – do not need to allocate their indirect costs or receive an indirect cost allocation.

That said, many public organizations allocate overhead to internal cost centers. In fact, when they do, they typically use the step-down method of allocating indirect costs. That is, they allocate organization-wide indirect costs to all cost centers first, then allocate service center costs, including their portion of the organization-wide indirect costs, to the mission centers.

With those assumptions in place, recall that:

- The Food Protection mission center averages 500 copies each day. Assuming 260 workdays/year, that is 130,000 copies (i.e., 500 copies x 260 days). In this case, the 130,000 copies are the relevant range or the amount of activity upon which our cost analysis is based. Assuming the Food Protection mission center would require twice as many copies, our per-unit costs and cost allocations would look quite different. Good cost analysis follows from clear, defensible assumptions about the relevant range of activity that will drive costs.

- The Animals and Pests mission center makes 250 copies each day but makes many more in the event of a communicable disease outbreak. Assuming no outbreak, that is 65,000 copies (i.e., 250 copies x 260 days).

- The Wastewater division makes 100 copies daily and up to 1,000 copies around six times yearly when processing complex permits. Let’s assume a typical surge in copies for a complex permit will last for five days. That would mean 230 typical days and 30 “surge days” (i.e., six permits x 5 days/permit). So total number of copies would be around 53,000 (i.e., typical day copies of 100 copies X 230 days + and surge days copies of 1,000 copies X 30 days).

From these figures, we can determine that the copier will make 248,000 copies each year (i.e., 130,000 copies + 65,000 copies + 53,000 copies).

If we divide the full annual cost of the copier by the number of copies ($21,380/248,000 copies), we arrive at a unit cost of $0.0862/copy (i.e., 8.62 cents per copy).

With those full costs established, we must ask how the Environmental Health Department should allocate the full costs of the copier cost center across the three mission center departments. Fortunately, this is easy to do because the copier cost center has a clear cost object (cost per copy), and each department/cost center measures the number of copies it makes. As a result, each department would be assigned copier center indirect costs at a rate of 8.62 cents/copy.

- Food protection would be assigned $11,206 (i.e., 130,000 copies X $.0862/copy).

- Animals and Pests would be assigned $5,603 (i.e., 65,000 copies X $.0862/copy).

- Wastewater would be assigned $4,569 (i.e., 53,000 copies X $.0862/copy).

Due to a rounding difference, the total adds up to $21,378.

With an appropriate allocation basis, it is possible to allocate any indirect costs in a similar way.

This copier example also shows why the cost center and cost object are essential to the cost allocation process. For instance, imagine that the copier was defined not as one cost center but as separate cost centers for large copying jobs (say, more than 500 copies) and small copying jobs, or for color copies vs. black and white copies. This would also require different cost objects, such as the “cost per black and white copy” or “cost per color copy.” The cost per black and white copy would presumably be less than the cost per color copy, and the cost per copy for large print jobs would presumably be less than that for small jobs. Different cost centers, cost objects, and allocation methods can mean substantially different answers to the question, “What does a copy cost?”

One potential drawback of the step-down method is that it allows “double counting” or “cross-allocation” of service center costs to service centers already allocated to mission centers. For example, recall that the annual full cost of the copier service center was $21,380. That full cost incorporated the indirect costs of the office manager’s time to manage the copier. Under the step-down method, the cost of the office manager’s time is allocated to the copier cost center, and the copier cost center costs are then allocated across the mission centers. But what happens if the office manager makes copies? Under this indirect cost allocation scheme, the office manager’s copies would not be reflected in the total volume of copies made, and the office manager would not receive any of the copy center’s costs. As a result, the mission centers subsidize the office manager’s copying by absorbing a larger share of the copy center’s costs.

In this particular example, those subsidies are a negligible amount. But in many other scenarios, cross-allocation of service center costs can significantly impact the full cost of a good or service. For instance, imagine a non-profit organization with three mission centers, a service center for the executive director, and a human resources service center. The human resources service center spends most of its time interacting with the executive director, as is often the case in small non-profits. If this organization uses the typical step-down approach, and it first allocates the executive director’s costs to the other service centers, then the full costs of the three mission centers will include a sizable subsidy for the costs of the executive director-human resource center’s interactions.

To address this problem, many public organizations instead use the double-step-down method. After each service center/department’s costs have been allocated once, each center/department’s cost not included in the original allocation is totaled and allocated again. To illustrate, let’s return to the copy center-office manager example above. If this allocation were done with the double-step-down method, the office manager’s copies would be included in the total copy figure. The copy center would first allocate its costs to the mission centers, excluding the office manager’s copies. Then in a second step, the office manager’s share of the copying costs would be allocated to the mission centers separately. This double-step method minimizes the cross-allocation of service center costs. For more on cost allocation methods for governments, see several chapters in Zach Mohr, ed. (2016), Cost Accounting in Government: Theory and Applications (New York: Routledge); also see the chapter “Cost Accounting and Indirect Costs” in Dittenhoffer and Stepnick, eds. (2007), Applying Government Accounting Principles (Lexis-Nexus Publishing).

DOUBLE STEP-DOWN COST ALLOCATION

The Iron River Transportation Agency (IRTA) has two mission departments – Rapid Transit and Para-Transit. Rapid transit uses high-speed trains and is highly equipment-intensive, while Para-Transit uses mopeds and is far more labor-intensive.

IRTA has two service departments: maintenance and administration. Management has decided to allocate maintenance costs on the basis of depreciation dollars in each department and administration costs on the basis of labor hours worked by the employees in each department.

The following data appear in the agency’s records for the current period. Allocate the service center costs to production centers using the step-down method and determine the relevant total costs. Begin with the maintenance department.

MISSION CENTERS |

SERVICE CENTERS |

||||

RAPID-TRANSIT |

PARA-TRANSIT |

MAINTENANCE |

ADMINISTRATION |

TOTAL COSTS |

|

Direct plus Distributed Costs |

$8,000,000 | $4,000,000 | $1,160,000 | $2,400,000 | $15,560,000 |

ALLOCATION FACTORS |

|||||

Indirect Depreciation Costs |

$3,000,000 | $800,000 | $200,000 | $2,000,000 | $6,000,000 |

Labor Hours |

10,000 | 40,000 | 20,000 | 10,000 | 80,000 |

We need to allocate two different service centers: Maintenance and Administration. It makes sense to allocate maintenance by depreciation dollars because depreciation is a proxy measure of each cost center’s scale of capital assets.

Depreciation costs, excluding maintenance, are $5,800,000 (i.e., $3,000,000 + $800,000 + $2,000,000). If we divide total maintenance costs by the total depreciation dollars excluding maintenance, we get $0.20 per depreciation dollar (i.e., $1,160,000/$5,800,000).

The Administration service center had $2,000,000 in depreciation, so we allocated it $400,000 in maintenance costs (i.e., $0.20 x $2,000,000). The Rapid Transit mission center had $3,000,000 of depreciation, so we allocated $600,000 (i.e., $0.20 x 3,000,000). Finally, the Para-Transit mission center had $800,000 of depreciation, so we allocated $160,000 (i.e. $0.20 x 800,000).

We then allocate administration by labor hours. This makes sense because supervising staff is the administration’s most significant cost driver. Since we’ve already allocated maintenance costs, let’s allocate the $2,800,000 costs from Administration (i.e., $2,000,000 in direct costs + $800,000 in indirect maintenance costs) to the mission centers based on the number of labor hours. There are 50,000 labor hours each at $56 per labor hour (i.e., $2,800,000/50,000). To Rapid Transit, we allocate $560,000 ($56 x 10,000 hours), and to Para-Transit, we allocate $2,240,000 ($56 x 40,000 labor hours). As the table shows below, we exclude Maintenance from this step since we’ve already assigned those costs to Rapid-Transit, Para-Transit, and Administration.

RAPID-TRANSIT |

PARA-TRANSIT |

MAINTENANCE |

ADMINISTRATION |

TOTAL COSTS |

|

Direct plus Distributed Costs |

$8,000,000 | $4,000,000 | $1,160,000 | $2,400,000 | $15,560,000 |

Allocated Maintenance Costs |

$600,000 | $160,000 | ($1,160,000) | $400,000 | – |

Step 1 Total Cost |

$8,600,000 |

$4,160,000 |

– |

$2,800,000 |

$15,560,000 |

Allocated Administration Costs |

$560,000 | $2,240,000 | – | ($2,800,000) | – |

Step 2 Total Costs |

$9,160,000 |

$6,400,000 |

– |

– |

$15,560,000 |

The total cost of the Rapid Transit program is $9,160,000 and the total cost of the Para-Transit program is $6,400,000.

Note, if we change the order of cost allocation to administration first followed by maintenance, total costs in the mission centers will be different. Recall that administration costs are allocated based on labor hours ($34.28 per labor hour, i.e., $2,400,000/70,000 hours). Maintenance costs will be allocated by depreciation costs ($0.49 per dollar of depreciation costs, i.e., $1,845,714/$3,800,000).

RAPID-TRANSIT |

PARA-TRANSIT |

MAINTENANCE |

ADMINISTRATION |

TOTAL COSTS |

|

Direct plus Distributed Costs |

$8,000,000 | $4,000,000 | $1,160,000 | $2,400,000 | $15,560,000 |

Allocated Administration Costs |

$342,857 | $1,371,429 | $685,714 | ($2,400,000) | – |

Step 1 Total Cost |

$8,342,857 |

$5,371,429 |

$1,845,714 |

– |

$15,560,000 |

Allocated Maintenance Costs |

$1,457,143 | $388.571 | ($1,845,714) | – | |

Step 2 Total Costs |

$9,800,000 |

$5,760,000 |

– |

– |

$15,560,000 |

The order of cost allocation affects the full costs in the mission center. Rapid-transit costs are higher (lower) if administration (maintenance) costs are allocated first. Irrespective of the order of “steps,” Total Costs for the department do not change.

Indirect Cost Allocation: Indirect Cost Rates

Cost drivers and allocation bases work well when the service has a clear cost objective and a measurable unit of service. Most public organizations, as described above, don’t have this luxury. Many don’t deliver services with measurable outcomes. Most public organizations’ costs relate to personnel, and personnel costs are not distributed evenly across clients or cases. Moreover, a growing number of public services are delivered through partnerships and collaborations where it’s often unclear how costs are incurred and murkier how those costs ought to be allocated across the partner organizations. Traditional cost allocation methods often don’t work in the public sector for these and many other reasons. And yet, it’s still critically important to measure and properly account for full costs, especially indirect costs that can be difficult to measure.

To address these problems, many public organizations rely on indirect cost rates. An indirect cost rate is a ratio of indirect costs to direct costs. For instance, a city police department might determine that its indirect cost rate is 15 percent. That means that for every dollar of direct costs like police officer salaries and squad cars, it will incur 15 cents of payroll processing, insurance, procurement expenses, and other indirect costs.

TAKING STOCK OF COSTS

Public organizations rarely have sophisticated cost tracking and measurement systems that you might find at manufacturers like Boeing, logistics companies like FedEx, or retail entities like Amazon. So how do budgeting and finance staff understand what a public organization’s services cost? There are three basic methods:

-

Time in Motion. Public organizations occasionally send analysts to see where and how employees spend their time. For instance, a city planning department might allow analysts into their office to watch how much time staff spend on different types of permits, appeals, and other activities. After observing the department’s activities for a sample of days over weeks or months, cost analysts can estimate how much time staff spends on each of their different activities and then build out cost estimates.

-

Self-reported Allocations. Some organizations ask staff to keep track of their own time, much like the billable hours method used by attorneys, accountants, and other professionals. Some of these tracking schemes are pretty detailed, requiring time reported in 15-minute intervals. Others are more general and allow for estimates on larger intervals like days or weeks.

-

Statistical Analysis. Cost accountants occasionally use regression analysis and other statistical tools to estimate the relationship between costs and services delivered. One of the most common is to determine the linear trend, if any, between total expenses and the volume of service delivered over time. Variation around that trend (i.e., the residuals from the regression analysis) suggests a potential pattern of variable costs.

Let’s illustrate this with a more detailed example. Surveys show that many local public health departments would like to offer more services related to hypertension outreach and management. Chronic health conditions like heart disease and diabetes are known to be related to high blood pressure, so better management of high blood pressure can affect public health in a substantial, positive way. However many citizens, especially those without health insurance, cannot access regular blood pressure screening and other services needed to identify and manage hypertension.

Say, for example, that Smallville County and Riverdale County would like to launch a new, shared hypertension prevention and management (HPM) program. Neither currently has a formal program in this area, but both offer services through a patchwork of partnerships with local non-profits. Smallville County has roughly twice the population of Riverdale County, and Riverdale’s per capita income and property values are 30 to 40 percent higher than Smallville’s.

What does it cost to deliver this service? As with most public health programs, the main costs will be related to personnel, namely public health nurses, outreach counselors, and nutritionists. The program will also require space and other overhead costs. The outreach and education components will require advertising, travel, and other costs. For a service-sharing arrangement to work, the two counties must decide how to share these costs.

Suppose the counties also agree in advance to share costs evenly. This approach is simple and straightforward. However, it ignores many of the program’s underlying cost drivers. Smallville has a much larger population than Riverdale, so more participants will probably come from Smallville. Simply splitting these costs “50-50″ means Riverdale will likely subsidize Smallville, an arrangement Riverdale’s leaders might find unacceptable.

So, what’s the alternative? Smallville could bill Riverdale for each Riverdale resident who participates in the program. They could use an allocation basis like population or assessed property values. A more cutting-edge scheme might be to share the costs according to the incidence of the chronic diseases the HPM program is designed to prevent. Each of these strategies demands a trade-off. Some are simpler but at the expense of fairness. Some require additional data that might result in an expensive cost measurement process or one that is not feasible. Others are more feasible but might place costs disproportionately on the population the program is designed to serve.

To begin, let’s assume Smallville will structure the new HPM as a cost center within the Health Behaviors division of its Public Health department. Let’s also assume that since HPM’s main “deliverable” will be blood pressure screening, it will define its unit cost as the cost per blood pressure screening performed.

Given those assumptions, Smallville’s budget analysts estimate that for the first year of operations, the HPM program will serve 400 clients, and its costs will include:

- Direct Labor. This includes seven full-time and one half-time licensed nurse practitioners who can administer blood pressure screening. The annual salary for each nurse practitioner is $67,500. The program will also employ a health counselor to guide clients on managing hypertension through healthier eating and fitness. The counselor’s annual salary is $74,500.

- Direct Non-Labor. Nurses and the health counselor will need to travel to visit clients and deliver outreach programs. Staff estimates total travel of 20,400 miles at $0.40/mile. The HPM program will also require medical supplies, office supplies, and a few capital items. Budget staff estimates $6,142 of annual direct non-labor costs for each nurse and $7,566 for the health counselor. This difference is due to a heavier expected travel schedule for the counselor. The program will also execute an annual contract, valued at $15,725, with a communications consultant who will develop and deliver a healthy eating outreach marketing effort in both counties. Even though most of these costs are related to labor, they’re considered non-labor “contractual” costs.

- Indirect Labor. Smallville County’s Health Behaviors Manager will supervise the HPM staff, and Smallville County’s Executive will provide policy direction and other leadership. A portion of both administrators’ salaries is allocated to HPM as indirect labor costs. HPM staff will also incur indirect labor costs like payroll support, accounting and auditing services, and procurement support. Budget staff estimates $10,456 of annual indirect labor costs for each nurse and $8,519 for the health counselor.

- Indirect Non-Labor. HPM staff must also have access to office space, liability insurance, association memberships, and other indirect non-labor costs. Budget staff estimates annual indirect non-labor costs of $4,799 for each nurse and counselor.

With that information and a few additional assumptions, we can begin to detail HPM’s cost structure and compute some indirect cost rates. The table below lists HPM’s direct, “observable” costs. We know the program will employ nurses and counselors, and we know it will demand mileage and the communications contract as direct, non-labor costs. These “observable” direct costs total $604,635, or $1,512 per client given the estimated 400 clients.

DIRECT “OBSERVED” COSTS |

|||

UNITS |

COSTS PER UNIT |

TOTAL COST |

|

Nurse Salaries |

7.5 | $67,500 | $506,250 |

Health Counselor Salaries |

1 | $74,500 | $74,500 |

Mileage |

20,400 | $0.40 | $8,160 |

Outreach |

$15,725 | ||

Total Direct, Observed HPM Program Costs |

$604,635 |

||

Estimate # of Clients |

$400 |

||

Cost per Client |

$1,512 |

||

IS IT ALLOWABLE?

One of the key questions when computing indirect cost rates is which indirect costs are allowable or reasonable. For example, in some cases, it’s unclear whether staff who contribute marginally to a program’s operations – such as development directors, general outreach coordinators, and others – should be included as an indirect cost. Certain types of training might be helpful, but not essential, for staff to understand their jobs and deliver the service. And of course, there’s always a reason to define indirect costs as broadly as possible, especially if you can recover those costs through some external funding source.

There are no national standards, per se, for what constitutes a relevant indirect cost. Each project, program, and funder is different. That said, the federal government has guidelines on what types of indirect costs it will reimburse. Many states and local governments also use these standards – or some adaptation of these standards – for their internal cost accounting. You can find more information on those guidelines in OMB Circular a-87: Cost Principles for State, Local, and Indian Tribal Governments. This publication is available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a087_2004.

But the much more important question is how we account for the indirect costs and for the direct costs that are more difficult to observe. The lower part of this table outlines those costs. When we include the indirect labor and indirect non-labor costs, we see the full cost of the program increases to $785,997, or $1,965/client. Or, put differently, the full cost of the program increases by more than 30 percent if we include all the indirect costs in our estimate of the full costs. Recall that Smallville County plans to bill Riverdale County for its share of program costs. If Smallville bills only for the direct costs, it undercharges Riverdale by nearly 30 percent. That is why it is important to measure full costs, especially when pricing services or requesting reimbursements for expenses incurred.

FULL COST, BY MAIN DIRECT LABOR INPUTS |

|||

NURSES |

COST PER NURSE |

TOTAL COST |

% OF COSTS |

Direct Labor |

$67,500 | $506,250 | 74% |

Direct Non-Labor Mileage |

960 | 7,200 | 1% |

Direct Non-Labor Outreach |

1,850 | 13,875 | 2% |

Other Direct Non-Labor |

6,142 | 46,065 | 7% |

Indirect Labor |

10,456 | 78,420 | 11% |

Indirect Non-Labor |

4,799 | 35,993 | 5% |

Full Cost of Nurses |

687,803 |

100% |

|

HEALTH COUNSELOR |

COST PER COUNSELOR |

TOTAL COST |

% OF COSTS |

Direct Labor |

$74,500 | $74,500 | 76% |

Direct Non-Labor Mileage |

960 | 960 | 1% |

Direct Non-Labor Outreach |

1,850 | 1,850 | 2% |

Other Direct Non-Labor |

7,566 | 7,566 | 8% |

Indirect Labor |

8,519 | 8,519 | 9% |

Indirect Non-Labor |

4,799 | 4,799 | 5% |

Full Cost of Counselor |

98,194 |

100% |

|

Full Cost of HPM Program |

$785,997 |

||

Cost per Client |

$1,965 |

||

What about potential indirect cost rates? According to these figures, 74 percent of the full cost to employ a nurse is direct labor costs, and 10 percent is direct non-labor costs (i.e., mileage, outreach, and other direct non-labor). It follows that the remaining 16 percent is indirect costs related, in a predictable way, to those direct costs. Each nurse and health counselor will be insured, have their payroll processed by the payroll office, occupy space, and so on. If those figures are predictable, we can assume the current indirect cost rate for nurses is 16 percent. For the health counselor, the direct costs are a bit higher at 76 percent. Direct non-labor costs are 11 percent, and indirect costs are 14 percent.

In practice, this means that in future budgets, the HPM program could assume that for every dollar it will spend on nurse salaries, it can expect to incur 16 cents of indirect costs, and for every dollar it will spend on health counselor salaries, it can expect to incur 14 cents of indirect costs (i.e., indirect cost rate).

Some organizations compute indirect cost rates based only on direct labor costs. In that case, the rate for nurses would be the indirect cost rate would be 22.6 percent – i.e., $10,456+$4,799)/$67,500. For healthcare counselors, the indirect cost rate would be 22.8 percent.

We can also consider an indirect cost rate for the entire HPM program. For that, we compare the total indirect costs to the total direct costs. Total indirect costs for the nurses are $114,413; for the counselor, $13,318. That means total indirect costs are $127,731. Total direct costs are $573,390 for the nurses and $84,876 for the counselor, for total direct costs of $658,266. The indirect cost rate would be 19.4 percent (i.e., $127,731/$658,266). Again, all these figures assume the HPM program serves 400 clients.

Information about indirect cost rates is relevant to many types of decisions. For instance:

- HPM staff might compare their indirect cost rate to the rates of other programs within Smallville County. If its rates are noticeably higher or lower, it might more carefully review its cost structure and how it manages its costs. If its rates seem grossly out of line with other units, it might request an additional review by Smallville County’s budget staff.

- The counties might use these rates when applying for federal or state grants or for support from philanthropic foundations to support the HPM program.

- The counties might eventually decide to contract out some or all of HPM’s operations to a non-profit healthcare provider. In that case, these rates would be a focal point for negotiating the per-client rate at which the counties would reimburse a prospective contractor.

- Other governments might review these rates as an initial indicator of whether they can afford their own HPM program.

EASY AS ABC?

Some governments – and many private sector organizations – try to address this problem through activity-based costing (ABC). ABC identifies the full cost of different activities within organizations that drive costs, regardless of the original cost center to which those costs were assigned. It then allocates those full costs according to changes in those underlying cost drivers.

If Smallville County followed an ABC model in the HPM example, the information services staff might have identified the unit costs of different types of information service requests. More complex activities, like the information-gathering about Riverdale County residents, would incur costs at a different rate than simpler activities. To the earlier point, this sort of small discrepancy could easily dissuade Smallville from continuing to participate in this sharing arrangement. A better alternative might have been to measure the number of hours or percentage of total time on this project attributable to gathering information specifically on Riverdale residents. And yet, the additional time and effort to gather that information might far outweigh the benefit of more precise cost allocation. This is a small-scale example, but it illustrates that every cost allocation basis comes with trade-offs that all the parties involved must understand and agree to upfront.

Cost Sharing Alternatives

Traditional cost allocation works best when it’s possible to observe when and where all the costs are incurred. When that information is unavailable, as is often the case for partnership arrangements that span multiple organizations, there are several alternative ways to organize a cost allocation plan. To illustrate, assume the full annual cost of HPM was $800,000 and that Smallville County must bill Riverdale County for Riverdale County’s share of those costs.

- Equal share. Total costs are divided equally across all participating partners. This is more typical for informal arrangements. It’s also common for services where it is unclear who “receives” or “uses” the service or to observe all the relevant indirect costs predictably and consistently. In equal share approaches, one partner often subsidizes the other, sometimes unknowingly. In the HPM example, Smallville would keep $400,000 of the costs and bill Riverdale its equal share of $400,000.

- Per capita. Total costs are divided by the population proportion in each partner jurisdiction. This approach is good for services without an observable “client” or discrete individual services. It’s less useful when population size is not the best cost driver or when the populations involved are different on some key characteristic that might affect the utilization of the service in question. Per capita sharing is often the most transparent way to share costs. In the case of HPM, recall that Smallville’s population is 240,000 and Riverdale’s population is 160,000. In other words, 60 percent of the population served resides in Smallville and 40 percent resides in Riverdale. Under a per capita model, Smallville would bill Riverdale $320,000.

- Cost Plus Fixed Fee. Personnel costs are often step-fixed costs, and it can be challenging to know when those costs will “step up” at higher levels of service (more on step-fixed costs below). To account for that uncertainty, some cost allocation strategies call for non-weighted cost sharing plus some fixed periodic fees. The fee part of the plan is designed to buffer the sharing arrangement against the uncertainty surrounding step-fixed costs. For HPM, one potential application of this method would be for the counties to share costs per capita but for Smallville to receive an annual payment of $35,000 at the start of its fiscal year to compensate in advance should it need to hire an additional nurse during the year. The cost-plus fixed fee model can also be used where overhead costs (e.g., space, utilities, administration, and accounting) would be shared one way, and incremental costs (e.g., costs for lab work or medical supplies) are charged based on volume.

- Ability to Pay. Some cost allocation arrangements are designed to make a service available where citizens and clients are otherwise unable to pay for it. In these cases, allocating costs according to the ability to pay makes sense. We can approximate the ability to pay through assessed property values, median household income, or other measures of income or wealth. In the HPM example, consider the following scenario: Riverdale’s median household income is $50,000, and Smallville’s is $40,000. Riverdale has a smaller population but is wealthier. In this case, Riverdale’s median household income ratio to Smallville’s is 1.25 ($50,000/$40,000). This is commonly known as a wealth factor. Recall that an equal share allocation is $400,000 for each jurisdiction. If 50-50 share is adjusted by a wealth factor, Riverdale’s share of costs would be $400,000 X 1.25, or $500,000, while Smallville’s share would be $300,000.

- Prevalence. In this method, the parties share costs according to the prevalence of the public health problem the service is designed to address. In the HPM example, the partners could share the total program costs according to observed instances of diabetes or heart disease. The logic here is simple: diabetes and heart disease tell us something about the expected number of people with hypertension. If the prevalence of the disease is not known, the partners can use a proxy, like socioeconomic status, to project the anticipated need for services in each population. In the HPM example, Riverdale’s higher overall wealth suggests its residents are at lower risk for hypertension compared to Smallville residents. Sharing by prevalence adds substantial complexity because cost sharing is now based on data from a series of measurements unrelated to costs. In this case, those measurements are the incidence of disease or an indicator of socioeconomic status, which can be difficult to measure reliably, and other health-related behaviors like smoking or medication adherence. That said, this approach is especially good where population, property values, income, and other measures vary too much among sharing jurisdictions to offer meaningful comparisons. In this instance, we assume Smallville will have an estimated 12,740 cases of type 2 diabetes during the coming year, and Riverdale County will have an estimated 5,460 cases. This strategy considers each county’s share of the total incidence across both counties. According to that logic, 70 percent of the cases will be found in Smallville and 30 percent in Riverdale. Allocating costs this way leads to a share of $560,000 for Smallville and $240,000 for Riverdale. Some versions of prevalence also incorporate a moving average so that one community does not incur huge costs in a single year, and costs are recovered over time.

- Weighted formula. This plan addresses some of the big problems with the per capita sharing approach. For example, in a weighted formula approach, the participants might agree to share total costs according to a combination of population, median household income, usage, and other factors. By incorporating these other factors, the cost apportionment method will better reflect differences in fixed costs in urban vs. rural areas, differences in travel distances within each county, and a wide variety of other factors that may affect service delivery. For HPM, assume that Smallville and Riverdale decide to share costs according to a three-factor formula that incorporates population, ability to pay, and prevalence of type 2 diabetes. This formula reflects both counties’ shared understanding of the cost structure and cost drivers of the HPM program. The counties, realizing the difference in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, agree to weigh that difference in prevalence more heavily in the cost-sharing formula. They agree to a three-factor formula where population accounts for 25 percent, prevalence is 50 percent, and ability to pay is 25 percent of the total costs allocated to each county. Recall that Smallville accounts for 60 percent of the population served by HPM, and Riverdale accounts for 40 percent. At the same time, Smallville accounts for 70 percent of the prevalence factor and Riverdale for 30 percent. We would apply that formula as follows:

- Cheng County: $800,000 X ((.6 X .25) + (.7 X .5) + (.44 X .25)) = $488,000;

- Duncombe County: $800,000 – $488,000 = $312,000

DIFFERENTIAL COST ACCOUNTING

In the previous section, we explained how to measure the full cost of a service. Those techniques assume we’re measuring the cost of the service for a given level or volume of the service. Until now, for instance, we’ve assumed our hypothetical HPM program will serve 400 clients a year. But sometimes, the more interesting question is: How do a program’s costs change if we deliver more or less of it? For instance, how does HPM’s cost per client change if we expand it to 500 clients? Or restrict it to 300 clients? These questions sound simple, but they require careful attention to different concepts. We turn to differential cost accounting when we want to know how costs change in space and time. Differential cost accounting is, simply put, comparing how costs change at different levels of output.

Cost Behavior

We know that what a service costs largely depends on how much of it we deliver. This is broadly known as cost behavior. Every cost type falls into one of three different cost behavior categories:

- Fixed costs do not change in response to the amount of service provided. In the HPM case, Smallville County owns some of its own blood pressure screening equipment, so the costs of acquiring equipment costs won’t change even if the HPM program delivers a lot more blood pressure screenings. There, however, is a caveat to this. It is reasonable to assume that fixed costs will not change within a relevant range. Relevant range frequently refers to capacity. If current demand exceeds capacity, we’ll need to incur additional costs to expand capacity (e.g., room size, equipment that is available, etc.).

- Step-Fixed Costs are fixed costs within a relevant range. Step-fixed costs are frequently personnel costs. A nurse, for example, can see eight patients per day, and a counselor can see five patients per day. They are paid a fixed rate, regardless of number of patients they see. That said, they will likely not have the time to see more patients than the current workload. Therefore, we need to hire an additional nurse if we expect to see more than eight patients daily and an additional counselor if we expect to see more than five patients daily. So, if nurse visits per day were 20, we would need to hire three nurses and have the excess capacity to see an additional four patients (i.e., three nurses x a maximum of eight patient visits = 24 visits per day).

- Variable Costs change directly in response to the amount of service provided. For the HPM program, this might include copies and other office supplies needed to process physician referrals and mileage required to travel to outreach sessions, among others.

- Mixed Costs (or Semi-Variable Costs) have both a fixed and variable component. Utilities and equipment lease agreements are frequently semi-variable, with a fixed monthly charge irrespective of use and rate per unit of service consumed. Returning to our example of the copier, the monthly rate is fixed and the per-page service fee would be variable.

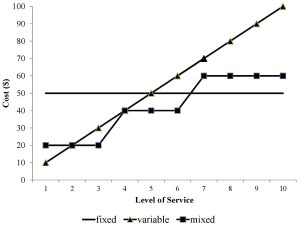

The figure below illustrates the cost behavior concepts for a generic, hypothetical service. The horizontal axis is the quantity of service provided, and the vertical axis is the total cost. The horizontal line at $50 represents a fixed cost. It does not change, regardless of the level of service provided. The triangle-marked line identifies a variable cost. Here we see each additional unit of service increases the total cost by $10, and that change is constant from zero to three units of service. The line marked with squares shows a step-fixed cost. Here, the cost is fixed at $20 from zero to three units of service. Once we reach four units of service, that total cost steps up to $40, where it stays fixed until seven units of service.

FIXED COSTS DEFINED DIFFERENTLY

“Fixed Cost” can mean different things in different settings. For our purposes, it means a cost that does not change in response to the volume of service delivered. By contrast, cost accountants sometimes use fixed cost to describe a cost that does not change during a given time period. This is an important difference.

It’s useful to think about a program or service with reference to these main cost behaviors. In fact, we can place most programs/services/organization units into one of six cost behavior categories. Those categories are outlined below, along with examples of each from typical non-profit organizations and government programs.

COST STRUCTURES WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

|

||

DIRECT |

INDIRECT |

|

FIXED |

Typical cost items: Salaried FTE program staff, program-specific equipment

Programs with this cost structure tend to:

Example program: Drop-in center for youth experiencing housing insecurity |

Typical cost items: Payroll services, facilities maintenance

Programs with this cost structure tend to:

Example program: Development/fundraising staff at a large non-profit |

VARIABLE |

Typical cost items: Program-specific inventory used by program participants

Programs with this cost structure tend to:

Example programs: Food banks, county prosecutor home detention programs (e.g., “ankle monitors”) |

Typical cost items: Inventory, equipment, commodities

Programs with this cost structure tend to:

Example program: Procurement staff within a non-profit hospital |

STEP-FIXED |

Typical cost items: Hourly/part-time program staff, shared facilities or equipment

Programs with this cost structure tend to:

Example program: Non-profit after-school daycare program |

Typical cost items: Liability insurance, shared facilities

Programs with this cost structure tend to:

Example program: Employee assistance program at a non-profit hospital |

It’s immensely helpful to think about cost behavior when we have to make decisions about how to design and fund programs. Consider this simple example based on the previously mentioned HPM program.

HPM staff have some rough budget projections. Their program is expected to incur fixed costs of $800,000 and variable costs of $400 per client. The program has expanded a lot since it launched, and it now expects to serve 550 clients but could serve up to 600 with current staffing levels. Meanwhile, nearby Emerald County has offered to pay $750 per client to expand the program to include an additional 50 Emerald County residents. Should Smallville and Riverdale counties agree to partner with Emerald County on these terms?

HPM’s cost behavior is outlined in the table below. Given its projected fixed and variable costs, at 550 clients, the average per-client cost is $1,855. If HPM scales up to serve 600 clients, its average cost will decrease to $1,734 per client. However, that average cost of $1,734 is still much higher than the $750 per client that Emerald County offering. On the basis of “average” unit costs, this proposal is a definite “no-go” for Smallville and Riverdale.

HPM PROGRAM COST CALCULATIONS |

||||

# OF CLIENTS |

FIXED COSTS |

VARIABLE COSTS |

TOTAL COSTS |

AVERAGE COST / CLIENT |

| 500 | $800,000 | $200,000 | $1,000,000 | $2,000 |

| 550 | $800,000 | $220,000 | $1,020,000 | $1,855 |

| 600 | $800,000 | $240,000 | $1,040,000 | $1,734 |

However, keep in mind the relationship between fixed and variable costs. Recall that HPM staff have said they can add 50 more clients without taking on additional fixed costs. If that is true, then the new cost to add a client is only the additional variable cost. Put differently, the average cost of each client is $1,734, but the marginal cost, or the cost of a new client, is $400. If HPM is reimbursed $750 per client, the additional “profit” is $350. If HPM makes this decision “at the margin” or with reference only to the marginal cost, it should take the deal with Emerald County. This is a good example of a service with positive economies of scale; the marginal cost of each unit of service decreases as the volume of service delivered increases.

Of course, there are trade-offs here. At 600 clients, the HPM program will operate at full capacity. HPM staff will almost certainly have to spend less time with clients. This could lead to a decline in the quality of service and could even increase staff burnout and turnover. But if we look just at the marginal cost, it makes sense for Emerald County to join the program.

This example also illustrates the key concept of sunk costs. Many fixed costs are for capital items like equipment, land, and buildings that can be bought and sold. A public health department can, in concept at least, recover some of those costs by selling those capital items. However, HPM’s spending on employee salaries, training, insurance, and many other costs cannot be recovered. Those costs are sunk.

Some economists argue that sunk costs ought to be irrelevant to future decisions. In other words, at the margin, all that matters are the future, measurable, variable costs. Of course, this is difficult in practice. In the HPM case, scaling up to full capacity will mean additional stress on staff, and perhaps more importantly, it would mean giving up the opportunity to take on additional clients without taking on additional fixed costs. These costs are much harder to measure, but they are key components of decisions about cost sharing. The key takeaway here is that when considering a service-sharing arrangement, be sure to consider both the marginal costs and the opportunity costs.

DIFFERENTIAL COST ANALYSIS

You are the director of the Department of Human Services for Algonquin Bay. One of your public health programs provides services to senior citizens and children. The full-time direct staff includes licensed nurses and drivers (senior citizen program only). The department has also hired a program administrator and a secretary to manage the 20 full-time program staff (17 nurses and 3 drivers). Total costs for the two cost centers are expected to be $1,459,620. The program expects to receive $829,400 in reimbursements from Medicaid. A family foundation has pledged to support your efforts with an unrestricted grant ($100,000).

CHILDREN |

SENIORS |

TOTAL |

|

Patient Visits |

18,200 | 9,360 | |

Nurses |

7 | 10 | |

Drivers |

– | 3 | |

Direct Costs |

|||

Nurses |

390,600 | 558,000 |

948,600 |

Drivers |

– | 113,400 |

113,400 |

Supplies |

45,500 | 23,400 |

68,900 |

Fuel |

– | 18,720 |

18,720 |

Total Direct Costs |

436,100 |

713,520 |

1,149,620 |

Indirect Costs |

|||

Depreciation (Vehicles) |

– | 10,000 |

10,000 |

Rent (Building) |

92,453 | 47,547 |

140,000 |

Administrator and Secretary |

56,000 | 104,000 |

160,000 |

Total Indirect Costs |

148,453 |

161,547 |

310,000 |

Total Costs |

584,553 |

875,067 |

1,459,620 |

Reimbursement Revenue |

455,000 | 374,400 |

829,400 |

Unrestricted Grant |

25,000 | 75,000 |

100,000 |

Total Revenue |

480,000 |

449,400 |

929,400 |

Surplus (Deficit) |

(104,553) |

(425,667) |

(530,220) |

Surplus (Deficit) as % of Costs |

-18% |

-49% |

-36% |

The Department recently received an unsolicited bid from a local non-profit. The non-profit has proposed to take on the senior citizen program if the city agreed to reimburse the non-profit at a rate of $65 per patient visit. Should the department accept this proposal? What are the policy tradeoffs of delivering this service via a third party?

Assuming the non-profit provides services to the projected clients (9,360), the direct cost of the contract would be $608,400 (=$65 x 9,360). The direct costs of the contract would be significantly lower than the agency’s direct costs ($713,520/9,360 = $76.23. Assuming the average costs do not change significantly as the number of clients increases (for the department and the non-profit), the department would be better off contracting out with the non-profit.

Before the department accepts the non-profit proposal, they should consider the ramifications of having a third party provide services to their clients. That includes the quality of service provided to the senior citizens, as well as the capacity of the non-profit to deliver services. Accepting the bid at a cost lower than the department average could be an indicator of efficiency. It could also be the case that the non-profit has understaffed its program, resulting in lower average costs per visit. An inspection of the non-profit facility and a review of the home-visit practices should be considered in the bid review process.

The budget analyst assigned to your agency has recommended that you eliminate the senior citizen program since its costs far exceed revenues. Should the Department accept this proposal? What are the policy tradeoffs of dropping a cost center (i.e., senior citizens)?

Dropping the senior program would eliminate direct costs only! The total costs for the children’s program would increase by $161,547 to $746,100 (i.e., $584,553 + $161,547 or $436,100 + $310,000). Assuming there are no changes to unrestricted grants received, the children’s center would receive $555,00 in revenues (i.e., 455,000 + $100,000), and the deficit would decrease from $530,200 to $191,100 (i.e., $555,000 – $746,100). The analyst’s recommendation would result in a smaller deficit if laying off the nurses and drivers in the senior citizen program is at no cost to the department.

While eliminating the senior citizen cost center cuts the deficit by more than $339,000, the program will no longer serve clients in need of outreach and support. There would likely be unanticipated costs associated with eliminating the program. For example, failure to monitor the health and well-being of senior citizens could lead to these clients being hospitalized. Costs associated with their hospital visits and inpatient care would more than likely exceed the savings projected here. Thus, the strategy would be short-sighted.

The budget analyst assigned to your agency has recommended that the program eliminate off-site visits (i.e., lay off all drivers). In other words, nurses will no longer make site visits but rather, their clients will come to one central location for all their appointments. What are the financial benefits of this proposal? What are the policy tradeoffs of pursuing this strategy?

Laying off the drivers in the senior program would cut costs for the program from $875,067 to $732,947 – the costs associated with the nurses (keep in mind eliminating the drivers would also eliminate the indirect costs for the program (i.e., depreciation of $10,000)). The cuts to the program would shrink the budget deficit from $425,667 to $283,547.

While eliminating drivers in the senior citizen program would shrink the budget deficit for the cost center and the program, the strategy assumes that senior citizens would be able to make the trip to see the nurses at the program office. We could therefore see the workload for the department drop significantly and nurses be underutilized. The clients would likely turn to alternatives like relying on emergency services, which could end up costing the city even more over the long run (e.g., the nurses would be underutilized if visits fall below current levels), and use of emergency services (in-patient or out-patient hospital visits) would likely cost the city more than the costs associated with having the drivers.

Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis

So far, we have reviewed how public managers can identify the full cost of their services and how that full cost changes as they deliver more or less of a service. Those are crucial questions that all good managers can answer.

However, public managers must often confront a different question: What should we charge for this service? They are also routinely asked a corollary question: What volume of service should we deliver, given that service’s cost structure? To answer these questions, we turn to a particular set of concepts within differential cost accounting known as cost-volume-profit analysis (CVP). CVP is how an organization determines the volume of activity needed to achieve its profit or mission goal. It is the price it needs to charge to break even or make a profit or the cost limits that it must manage to achieve its profit or mission goal. CVP analysis is usually done for a particular program or service within an organization. The basic equation is:

Profit = Total Revenue – Total Costs

From this discussion so far, we also know that Total costs = Fixed costs + Variable costs. And since fixed costs are fixed, we can represent the cost equation as:

TC = a + bx

Where TC = total costs, a = fixed costs, and b = variable costs. We also know that total revenue is simply the price of service (p) times the volume of service delivered (x). That said, we can show the fundamental profit equation as:

Profit = px – (a + bx)

For any service, the break-even volume is the point at which total revenue (px) equals total costs (a + bx). To illustrate how we use this formula, let’s go back to the Environmental Health Department’s copier. Assume for the moment that the county government’s leadership wants to make copying more affordable, so it caps the price of copying at 7 cents per copy. At that price, how many copies must the copier center deliver each year to break even? In other words, what’s its annual break-even volume?

We know that the copier cost center’s fixed costs (a) include $6,000 for the machine rental, $900 for machine maintenance, and $1,500 for its space allocation. Let’s also assume electricity and the office manager’s time allocation are fixed costs of $180 and $100, respectively. So total annual fixed costs are $6,000 + $900 + $1,500 + $180 + $100, or $8,680.

Variable costs (b) are the largest cost items. Recall that last year the copier made 248,000 copies. Total paper costs were $10,000, so the per-copy cost for paper is ($10,000/248,000), or $.04/copy. Total printing cartridge costs were $2,700, so the per-copy cost for printing cartridges was ($2,700/248,000), or $.011/copy. These two variable costs together give us total variable costs of $.051/copy.

At break-even, profit = 0, so we can re-arrange the fundamental profit equation to px = a + bx. Since the price per copy is capped, per management’s policy, at $.07, we can then express this equation as:

$0.07x = $8,680 + $0.051x

To solve, we first subtract $0.051x from both sides, leaving us with $0.019x = $8,680. To solve for x, we divide both sides by $0.019, and we’re left with x = 456,842. In other words, at 7 cents per copy, the copier cost center’s break-even quantity is 456,842 copies. That’s nearly twice as many copies as it produced so far. Management might want to rethink this decision.