6 Budget Strategy

BUDGET STRATEGY: GETTING THE DEAL DONE

With a more sophisticated understanding of budget-making processes, public managers can answer a variety of questions and management concerns:

- How is “managing costs” different from “managing a budget”?

- What’s the best way – financially and politically – to respond to a potential budget cut? To respond to a possible budget increase or expansion?

- How can we structure budget processes to minimize conflict and maximize employee engagement?

- How does the budget timeline, namely when new information is introduced to budget decision-makers, affect how the budget is made?

- What are decision-makers’ key concerns throughout the budget process? How do loss aversion, incrementalism, and parochialism affect budget-making?

- How does the format and presentation of a budget document affect how staff, clients, and other stakeholders perceive it?

- Why do governments’ actual budget processes regularly deviate from their statutory or legal budget processes?

- What are the most and least effective ways to engage citizens and other stakeholders in the budget-making process?

In the late 1990s, several dozen people died in major house fires throughout the City of Seattle. Critics blamed the Seattle Fire Department for its slow and insufficient response to those fires. The Fire Chief accepted that criticism and urged the City’s leaders to invest in significantly upgrading the Fire Department’s facilities, equipment, and training. Then-Mayor Greg Nickels proposed a new, 10-year, $197 million property tax levy to pay for that upgrade, and voters approved that levy in 2003. The centerpiece of that levy was a plan to rebuild or refurbish 33 fire stations.

In 2015, the City announced it had spent $306 million on those fire station projects. Of the 33 projects included in the plan, 32 had exceeded their original budgets. Many had cost twice their initial estimate. And the program is not yet complete. The City expected to spend at least $50 million more from other resources to complete those projects over the next five years.

How did this happen? How can a major city program staffed with many sophisticated budget and finance staff over-run its budget by more than 50 percent?

The problem is best captured by the late, great Yogi Berra’s adage that “Predictions are hard, especially about the future.” Costs of basic materials and labor change all the time, so it’s difficult to forecast those costs seven to 10 years into the future. Indeed, basic construction costs increased by around one-third from early 2005 until late 2007. Moreover, during the ten years of the program, professional standards for firefighters changed. Under the new standards, fire stations must now have better training and fitness facilities, better information technology, and other upgrades that added costs to the project.

To others, the problem is politics. According to some accounts, Mayor Nickels’ staff estimated the fire station program would cost around $300 million. The Mayor, however, did not believe voters would approve that large a tax increase. So instead, he proposed the highest possible levy he believed would pass, and he assumed the fire stations could be built at lower costs or that additional money for the program would come from future city budgets. Whether you believe the problem is forecasting, politics, or something else, it is clear that the legacy of the fire station levy is two-fold: better fire protection and, presumably, closer scrutiny of future long-term capital projects.

This story illustrates the central point of this chapter: How we make a budget is just as important as the revenues and spending proposed within it. Consider, for instance, how changes to the City’s budget process might have produced a different outcome for the fire station levy:

- If the program had not required voter approval, Mayor Nickels might have proposed a much larger levy that better reflected the full cost of the program.

- At the same time, if the City had paid for the full cost of fire stations out of general fund resources that did not require voter approval, those projects might have crowded out the Mayor’s other high-priority projects in areas like economic development and affordable housing.

- If the City Council had better access to more sophisticated cost estimates earlier in the approval process for the new levy, they might have supported a higher requested amount or been willing to spend additional city resources.

- If the City Council members were elected by districts (as they are today) rather than at-large (as they were then), then specific members would have had a stronger incentive to monitor the costs and timing of fire station projects within their districts. That might have produced more substantial changes to the program at both the planning and implementation stages.

- If the City’s capital budgeting process had more stringent accountability features, then the mayor might have reduced the budget for projects scheduled later in the program once it was clear that the first few projects had run over budget.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Recognize the key components of a public organization’s budget timeline/calendar and formal/legal budget process.

- Recognize the different ways that we define “budget balance” and the implications of those various definitions.

- Recognize that budgets ensure fiscal accountability but do not guarantee financial solvency.

- Know the typical sources of conflict and compromise in the budgeting process.

- Know managers’ basic strategies to expand their budget authority or respond to potential cuts.

- Acknowledge the effectiveness of “doing nothing” as a budget-cutting strategy.

- Recognize when and why an organization’s budget for a service might be quite different from what that service costs.

“Don’t tell me what you value, show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.”

President Joe Biden

BUDGETS ARE A STATEMENT OF OUR VALUES

Budgets frame values that permeate society. They translate those values into policies and programs and communicate priorities to stakeholders. Budgets provide information for policymaking, public scrutiny, and accountability. Budgets must speak to multiple audiences, including legislative body members, taxpayers, employees, and oversight agencies.

A government’s budget is a prospective document that shows policy priorities and how it plans to pay for them. It facilitates the stewardship of resources – that expenses are reasonable, necessary, and incurred in the pursuit of the organization’s mission. It identifies proposed spending and the means of financing proposed expenditures for the budget year (or multiple years). To that end, budgets must present a summary of revenues by source, expenditures (or expenses) by policy area, and any other source of funds (e.g., bond proceeds or proceeds from the sale of assets).

Budgets guide policy implementation and assess performance (program and financial performance). To that end, budget documents should include a statement of objectives for each unit within the organization (e.g., department, divisions, offices, or programs) and provide objective measures of performance and outcomes.

OPERATING VS. CAPITAL BUDGET

Most state and local governments have two different budgets: the operating budget for recurring expenditures and a capital budget for non-recurring capital expenditures (e.g., land acquisition and improvement costs). All day-to-day expenses of operating core programs are reported in the operating budget. However, capital expenditures may be included in the operating budget if they are recurring expenditures (e.g., purchase of computing equipment). Operating budgets frequently include spending on existing capital investments, including maintenance costs and principal and interest payments on outstanding debt obligations that finance infrastructure improvements.

Capital budgets typically include a capital improvement plan (CIP) that identifies long-term capital spending needs over a five- or 10-year period. The capital budget will identify funding sources over multiple years, including General Fund revenues, special taxes, user charges or fees, federal grants, reserve funds, and long-term debt (proposed or approved).

Creating and justifying capital expenditures is far more challenging for most state and local governments because these investments are not visible but considerably more expensive. Consider, for instance, that 70 percent of infrastructure assets are underground, but it costs $140,000/mile/year to maintain roads.

In some instances, spending on capital improvements may require voter approval, as related expenditures are paid for using special tax revenues (e.g., capital projects property tax levy) or general obligation bonds. Borrowing is an acceptable form of financing capital improvements so long as the repayment period does not exceed the asset’s useful life. Borrowing should not be used to balance the operating budget. Given the significant costs associated with capital improvements and their potential impact on operating costs, operating budgets, and capital budgets are inextricably linked, as substantive changes in one will impact the other and vice versa.

Most people believe—incorrectly – that governments adopt a single budget. In reality, governments adopt multiple budgets, known as appropriation bills (or spending bills). Up to 13 different appropriation bills must pass both houses of Congress before they go to the President. Appropriation bills may be combined into an omnibus appropriations bill. State and local governments pass fewer bills. The Washington legislature, for example, approves three separate appropriation bills – operating budget bill, capital budget bill, and transportation budget bill.

Governments adopt separate budgets for off-budget entities that are reported in a separate stand-alone budget. While the Federal Reserve System (the Fed) is part of the federal government, the agency has autonomy over its finances with interest on U.S. government securities, foreign currency investments, fees for services provided to depository institutions (e.g., automated clearinghouse operations), and interest earned on loans to banks covering its operating expenses with remittance of any excess funds to the U.S. Treasury. Government-sponsored enterprises, such as the Federal Home Loan Banks, also fall outside the federal budget processes as they are privately owned, and their debt does not bear the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

ANNUAL VS. BIENNIAL BUDGET

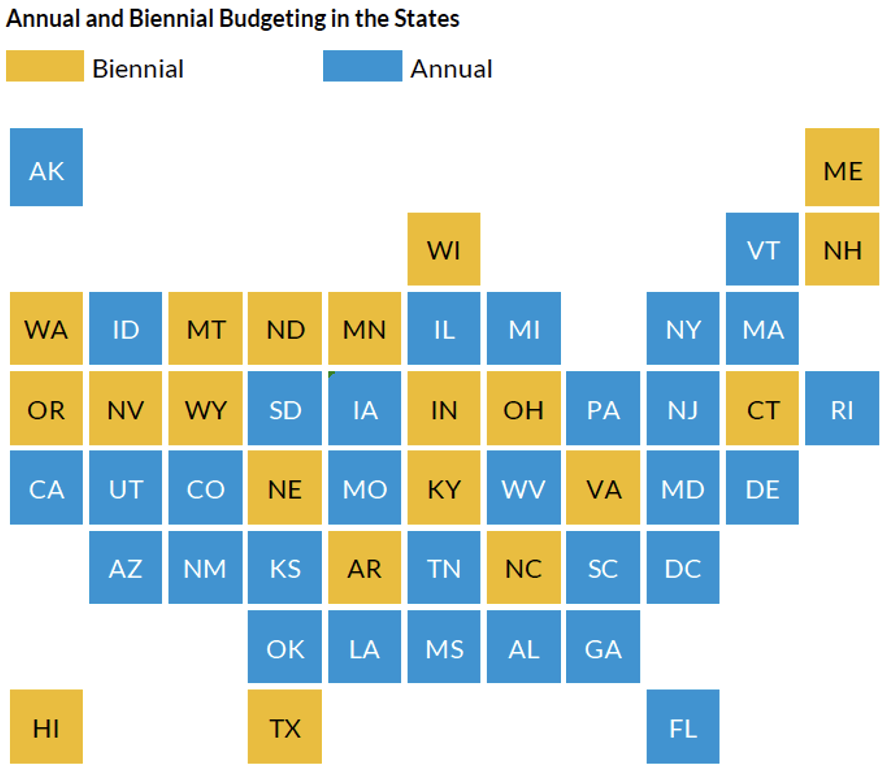

A vast majority of states prepare and present an annual budget. Several states prepare a biennial budget with an annual session. In other words, the state prepares and presents a two-year budget and adjusts the biennial budget at the end of the first year.

Biennial budgeting states generally enact separate budgets for each fiscal year at once. They include Arkansas, Connecticut, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. True biennial budgeting—enacting a single two-year budget—is rare, although still practiced in North Dakota and Wyoming. States with biennial budgets and biennial sessions are some of the smallest in the nation — Montana, Nevada, and North Dakota. The exception here is Texas.

Source: National Association of State Budget Officers and Tax Policy Center

INCREMENTALISM AND BUDGET REFORMS

Budgeting is many things to public organizations. It’s a mechanism to plan and develop a strategy for the coming year. It’s a tool to evaluate how well managers manage. It’s a way to evaluate if and how an organization’s resources are connected to its priorities. It’s a tool to get feedback from key stakeholders about an organization’s successes and failures. For governments, the budget is a legally binding document that commits it to a spending plan for the coming year(s). But fundamentally, budgeting is a form of politics. Resources are scarce, and budgeting is the process by which organizations allocate those scarce resources. As such, budgeting is about managing conflict.

Budgeting in governments, and most large bureaucratic institutions, is an incremental process. That is, the focal point for each year’s budget is an incremental increase or decrease over last year’s budget. Put differently, there’s an old adage: “Most budgets are last year’s budget plus three percent.” Since the Great Recession, most budgets have been last year’s minus three, five, or 10 percent. For budget policymakers, conflicts and compromises are often around that annual percentage change or increment. This assumes that last year’s budget – or base budget – fairly represented the organization’s goals and priorities. If this is not true, then debating on incremental change will amplify the disconnect between resources and priorities. In fact, for most public organizations, that disconnect is persistent and pervasive.

Historically, governments have prepared line-item budgets that place significant emphasis on inputs. Unfortunately, line-item budgets do not present information in a format that connects the mission to the organization’s resources. Most have experimented with various budgeting models designed to “reform” the line-item format and incrementalistic tendency. One of the most popular reform strategies is to allocate resources not through political bargaining but in a more mechanical or formula-driven way driven by priorities or goals. For roughly 50 years, one of the most popular strategies has been performance budgeting. In this format, the organization allocates resources not according to inputs or line items like salaries or supplies but rather according to the level of overall resources, regardless of inputs needed to achieve some desired goal or outcome. Some governments extend this model into a Price of Government or Priorities of Government approach. Under this model, citizens identify the levels and outcomes of government services most important to them, and the government allocates packages of resources to achieve those outcomes.

Performance budgeting and the “Priorities of Government” approach are not mutually exclusive. Cities like Redmond, WA, and Somerville, MA, have implemented performance-based budgeting programs that are tightly connected to strategic priorities. In the Somerville model, departments orient their budget requests around outcomes rather than budget inputs or line items. For example, the library system requests its budget in terms of the cost per library patron served, not just in terms of payroll, commodities, equipment, and other line items.

A few state and local governments have experimented with versions of zero-based budgeting (ZBB). Under ZBB, the organization assumes there is no such thing as a base budget. Each year, departments and programs must justify everything in their budget. Much of the money state and local government spend is “required by law” or “necessary for public safety,” so a large portion of a government’s budget cannot be cut through a ZBB process. Some versions of ZBB require departments or programs to connect their non-required spending to the organization’s strategic goals or priorities. Proposed spending most closely connected to those goals will likely make its way into the final budget and vice versa. In some ZBB models, departments and programs must present decision-makers with “scenarios” or “decision packages” that identify what will happen if their department or program does not receive a portion of its base budget. All these innovations are designed to remove some or all of the pure political bargaining from budgeting.

That said, most governments and non-profit organizations continue to practice traditional, incremental, line-item budgeting.

OPERATIONALIZING EQUITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE IN STATE AND LOCAL BUDGETS

City of Seattle Race and Social Justice Initiative (RSJI) is a citywide effort to end institutionalized racism and race-based disparities in government. The Race and Social Justice Initiative leads with racism because race has shaped institutions and policies in the U.S. in ways that have prevented racial equity. When the City of Seattle launched RSJI in 2005, no other government had ever undertaken an effort that focused explicitly on institutional racism. Over the years, several city and county governments have initiated equity and social justice initiatives in their budget processes, including King County (WA), Minneapolis (MN), Madison (WI), Portland (OR), and San Antonio (TX), to name a few.

To be effective, race and social justice initiatives will require concerted efforts in every department in every state or local government. The Seattle Office for Civil Rights leads equity and social justice initiatives in the City and supports the City’s departments and staff. Every department has a “Change Team” – i.e., teams facilitating discussions on race, racism, and strategies to overcome institutional barriers to racial and social equity. Departments develop processes that explicitly guide the development, implementation, and evaluation of policies, programs, or initiatives to promote racial equity. The City of Seattle’s Racial Equity Toolkit guides the process and requires departments to

-

define racially equitable community outcomes associated with their program or initiative, focusing on key opportunity areas (e.g., education, community development, public health, environment, criminal justice, and affordable housing)

-

analyze qualitative and quantitative data, and engage community partners. Conversations with community stakeholders and comparative data would help identify the root causes or factors that can be used to explain racial inequities (e.g., lack of access, bias in processes, lack of racially inclusive engagement)

-

use data to design programs, policies, or initiatives. They must also outline the expected outcomes (benefits) and unintended consequences (burdens). Recognizing that not all policies will have equitable results, departments must identify strategies that would lead to a long-term positive change or re-align the department’s work to achieve racially equitable outcomes

-

evaluate programs to raise awareness and be accountable. Evaluations would then be used to track impact and identify issues initiatives or programs could not address.

Social justice initiatives face significant challenges, the largest being existing mandatory expenditures, the incremental nature of budgets, and the pervasiveness of restricted revenues, making it extremely challenging to shift resources to under-resourced programs or policy priorities where racial inequities are prevalent. Without new revenues, preferably from progressive taxes, social justice initiatives will have to compete for limited resources.

THE BUDGET PROCESS

Public managers can’t control many of the factors that affect their budgets. Managers in government can’t control the broader economy. Non-profit managers can’t do much to affect the financial health of the foundations that grant them money or individuals who support them through donations. Managers across the public sector can do little to affect rising costs for employee health care, new technology, wages and salaries, and other factors that drive growth in expenses. The best we can do is understand these trends, forecast them to the best of our ability, and help policymakers understand the trade-offs these trends put in play.

But public managers can control how they make their budgets, also known as the budget process. In fact, the process is the only part of budgeting that public managers can control. In particular, you alone can answer many of the key questions surrounding each of the three main budget process concerns:

- Who proposes the budget? Do you develop and propose your budget on your own? When developing your initial assumptions, do you solicit input from program managers or other subordinates, your board, council or other policy leaders, outside funders, or other key stakeholders? Do you ask department heads or other subordinates to develop and submit their budgets?

- What information is introduced into the budget process, and when? Do you share the key budget assumptions with program managers, line staff, and other stakeholders? Do you connect budgeted spending with key performance targets? If so, do you make those targets available to other stakeholders? If your budget calls for cuts, do you share when and how those cuts will happen? Do you explain why you chose the cuts you chose? Do you share that information with the entire organization at once or through meetings with individual program managers/department heads/etc.?

- Who decides on final budgeted revenues and spending? Do you afford program managers/department heads/etc., the latitude to propose their own final budget? Does your council/board approve the budget in one action or in stages? If you have the authority to make budget amendments or re-appropriations? Do you use it, and when? Does your budget include both operations and capital projects, or just operations?

For this and many other reasons, it is important to understand some of the main features of public organizations’ budget processes. This discussion is focused on governments’ budget processes, mostly because those processes are comparable and are often prescribed by law. That said, many of the basic features of those processes can also apply to non-profits. Moreover, non-profit managers need to understand how government budgets are made, given the centrality of government funding to many non-profit organizations.

BUDGET PROCESS

STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS

The budget processes of state and local governments share some common characteristics. Most governments follow these basic steps:

- Strategic and Department-Level Planning: This process often begins five to six months before the start of the next fiscal year. The chief executive (governor, mayor, city manager, county administrator, etc.) will issue a budget call highlighting their policy priorities. Department heads and program managers must prepare budgets based on the executive’s priorities and their own spending needs. The budget call will include information about expected revenue changes – based on the prevailing economic environment and detailed instructions and assumptions that must be used to prepare the budget (e.g., cost of living adjustments, and mileage rates). The call will also contain detailed instructions on how agencies and departments are expected to prepare budget proposals (e.g., format) and budget calendars to ensure program and departmental budgets are prepared in a timely fashion.

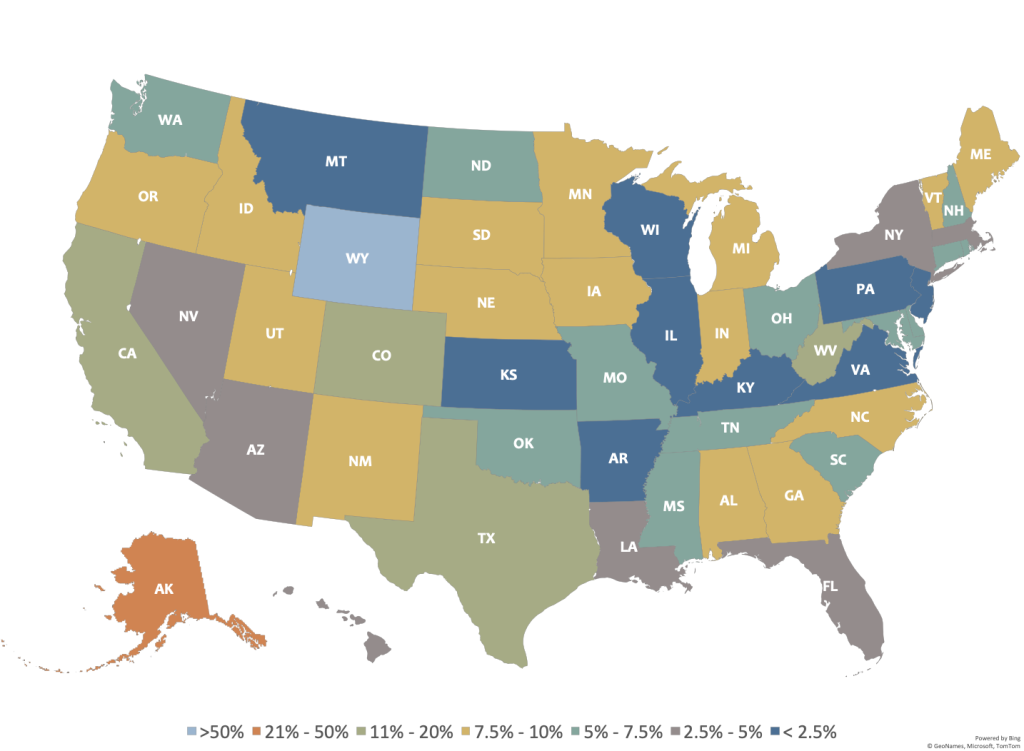

- Revenue Forecasting: For most state and local governments, revenue forecasting begins with national and region-specific forecasts of economic activity. For this, governments frequently use proprietary and national data to predict changes in population, wages, employment/unemployment, income, consumer confidence, market performance, and assess changes in key sectors in the state or region. Regression models are frequently used to forecast tax revenues. These models incorporate historical data and inputs on expected changes in policy (e.g., changes in marginal income tax rates). Most states and large local governments have a consensus revenue forecast group comprising executive and legislative staff. In seven states, the governor’s office alone prepares the estimates (Arkansas, Georgia, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and West Virginia). Others hire consulting firms that prepare, present, and revise multi-year revenue forecasts (Hawaii, Nebraska, Nevada, and Washington). Revenue forecasting is an ongoing process that is revised throughout the preparation, approval, and execution phases of the budget cycle. Revenue officials (treasurer, chief financial officer, finance director, etc.) frequently track economic trends, compare revenue projections to actuals, and use that information to recommend changes during the budget year or the following fiscal year. Some governments’ revenues are so volatile that within-year budget changes are frequently required. Volatility in revenues is a function of the volatility of the revenue stream and the share that the stream represents. For example, increased reliance on taxes on oil and minerals (also known as severance taxes) means states like Alaska, North Dakota, and Wyoming have higher volatility scores compared to states like Texas and Pennsylvania, as the latter report a smaller share of revenues from severance taxes. Personal income and sales taxes are typically more stable, while corporate income taxes, like severance taxes, are significantly more volatile.

REVENUE FORECAST VS. CASH FLOW FORECAST

Forecasting has increasingly become an important fiscal planning tool. As the name suggests, to forecast is to “predict or estimate future events.” This is often challenging in volatile economic environments. Finance officers will forecast revenues and incorporate estimates in the proposed and approved budget. Proposed and approved budgets are the basis for preparing cash flow forecasts (also known as cash budgets). Unlike revenue forecasts, which are multi-year projections, cash flow forecasts are frequently on a monthly basis. They translate an adopted budget to monthly cash inflows (receipts) and cash outflows (expenditures). This exercise is especially important if cash flows are lumpy. For example, cash inflows from sales taxes or cash outflows for salaries and benefits are monthly and more or less predictable. However, cash inflows from property tax or cash outflows on debt service are lumpy, with payments on a quarterly or semi-annual basis. Similarly, non-profits will receive sizeable cash donations at the end of the year or following a capital campaign/fundraising event. They will frequently be awarded grants and contracts but on a reimbursement basis. That means they’ll incur costs – and make payments – before reimbursement is received. Therefore, managers need to plan when and to what extent they’ll draw on existing cash reserves, liquidate investments, tap their line of credit, or issue short-term notes. Conversely, they’ll use the cash flow forecast to plan how they will restore reserves, invest in safe money-market instruments, or pay off short-term debt.

- Executive Preparation: Once budgets are submitted to the executive office, budget staff will review departmental and program budget requests and use these requests to prepare the proposed budget. That’s not to say that departmental and program budget requests are adopted as is. In fact, department heads and program directors are often asked to present and defend their budgets, especially if budgets are not consistent with the executive’s priorities or exceed budgeted allocations.

- Legislative Review and Adoption: The legislative review process, which often integrates public hearings, begins one to two months before the start of the fiscal year. Legislators will review the executive’s proposed budget, question department and agency heads about their spending plans, and recommend changes that would be included in the final appropriations bill or approved budget. A vast majority of legislative bodies in government will hold public hearings. For states, hearings are part of the regular budget legislative session. For local governments, budget hearings are typically stand-alone public meetings. Budgets are often adopted two to three weeks before the start of the fiscal year, though, in some instances, budget adoption may be delayed. Once legislators pass a budget, the chief executive (governor, mayor, city manager, county administrator, etc.) will sign it. Governors in 44 states can use their line-item veto powers to reject parts of the legislative budget even though doing so would infringe on the legislature’s appropriation authority. (i.e., power of the purse). Vetoes can be overridden, typically with a legislative super-majority vote (three-fifths or two-thirds); otherwise, vetoed items do not become part of the approved appropriation, and the deletions or deductions stand.

BALANCED OPERATING BUDGET AND BALANCED BUDGET REQUIREMENTS

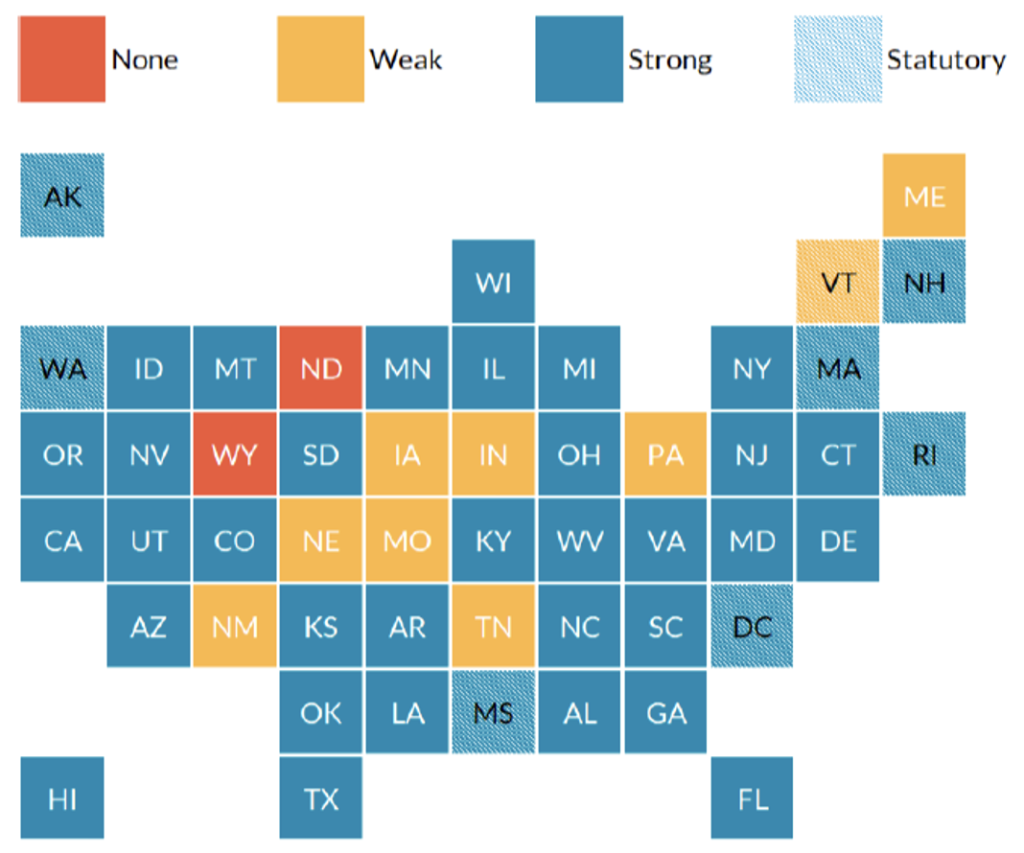

Balanced Budget Requirements (BBRs) are constitutional or statutory rules that prohibit states from spending more than they collect. For some governments, this means budgeted revenues must equal or exceed budgeted expenditures when the budget is passed. This is also known as balance “at adoption.” For others, it means budgeted revenues and expenditures must equal actual revenues and expenditures, also known as balance “at conclusion.”

In most states, the BBRs apply to just the General Fund; in others, the requirement applies to other governmental funds. In some governments, budgeted revenues and expenditures must equal or exceed actual revenues and expenditures at periodic intervals throughout the fiscal year.

Strong balanced budget requirement meets one or more of the following criteria: 1) requires the governor to sign a balanced budget; 2) prohibits the state from carrying over the deficit into the following year or biennium; or 3) requires the legislature to pass a balanced budget, accompanied by within fiscal-year fiscal controls or limits on supplemental appropriations. A statutory designation indicates that all balanced budget rules in that state are statutory, otherwise, the balanced budget rules are in the state’s constitution.

Research shows stricter BBRs – particularly those that prohibit states from carrying over deficits into the following fiscal year – are associated with rapid spending adjustments resulting in greater spending volatility as governments cut spending to meet the balanced budget requirement. In some states, BBRs have incentivized unsound budgeting and accounting practices, including frequent use of inter-fund transfers, underestimations of long-term obligations, and the frequent use of asset sales. That said, states that have strict BBRs are more likely to maintain higher reserve balances. The presence of balanced budget laws and higher-than-average reserves means that these governments are more likely to have a higher credit rating and as a result, their borrowing costs are lower.

Source: Tax Policy Center Briefing Book

- Implementation: Once the budget is approved, department heads and program managers will implement the approved budget over the next 12 months. Most organizations anticipate changes in forecasted revenues and budgeted spending. They’ll plan for mid-year adjustments, some of which may require formal modifications to the adopted budget. The central budget office will closely monitor the execution processes and adjust next year’s budget instructions accordingly.

- Audit and Evaluation: This stage starts at the end of the fiscal year. It can take many months, depending on the organization’s size, the complexity of the jurisdiction’s chart of accounts, the size, and the professional skills of budget staff and treasury officers, to name a few. Every organization must “close its books” and prepare financial statements before a financial audit. They will also engage in evaluation processes on program effectiveness. The Governmental Accountability Office (GAO) is the audit and evaluation arm of the federal government. Two tasks include “auditing agency operations to determine whether federal funds are spent efficiently and effectively” and “reporting on how well government programs and policies are meeting their objectives.”At the state level, the state auditor’s office would prepare the government’s financial statements and act as watchdogs over state agencies performing internal financial and performance audits. In 24 states, auditors are elected (therefore partisan). Appointed auditors serve as nonpartisan officials.

Even though the stages of the budget cycle are presented here as separate and distinct, they overlap a great deal in practice. For example, the budget’s preparation typically begins six to 18 months before the start of the fiscal year, depending on whether the budget is annual or biennial. Thus, when the government is preparing next year’s budget request, it is implementing the current year’s budget and, in some instances, completing audit reviews, performance evaluations, and financial reporting of the prior year’s budget.

Cities, counties, schools, and special districts generally follow the same basic process. In Washington State, most local governments follow a January 1 fiscal year. The mayor/executive/superintendent’s staff review departments’ budget proposals throughout the late summer and early fall and propose a budget in early September. The Council/Board debates the budget and revises it in late fall and early winter. At the City of Seattle, those proposed changes are articulated in Green Sheets that suggest a change to the Mayor’s proposed budget. State law requires a passed budget by December 2. Most local governments do not have the same executive-legislative tensions as the state and federal governments, and local budget processes are rarely as formal. Still, the same basic processes, institutions, and incentives are at play.

BALANCING STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT BUDGETS AMID THE COVID-19 RECESSION

Unlike the federal government, state and local governments must balance their budgets within the budget period or in the next budget period (see Balanced Budget Requirements). Additionally, existing laws prohibit state and local governments from using borrowed funds to pay for operating expenditures.

Practically every economic forecast predicts that the fiscal shock from the COVID-19 recession will be greater than the Great Recession. A prolonged recession and sluggish recovery would likely mean state and local governments must make significant budget cuts. We know from prior recessions that these cuts are more likely to occur in core public services, including healthcare, assistance to older people, and education, as these programs make up more than three-quarters of state or local government spending.

What will these governments do in the near term? Immediate expenditure responses will include hiring freezes, salary, and cost of living adjustment freezes, limits on the use of overtime, improved productivity by streamlining program delivery, cost-effective partnerships with other governments, non-profit organizations, and the private sector, audits of routine expenditures for savings, budget savings following reduced hours of operations, and data-driven targeted cuts in key programs and services. That said, balanced budget requirements frequently necessitate across-the-board (ATB) cuts – and practically every state and local government will use ATB cuts to address projected deficits. In the medium term, governments will likely eliminate programs and close facilities. In the long term, they’ll lean on layoffs, furloughs, cuts to employee benefits, and delayed payments to vendors and other governments.

On the revenue side, they’ll tap into reserve funds (e.g., Budget Stabilization Funds or unassigned General Funds balances) and rely on inter-fund (internal) loans to ease the cash flow crunch. They’ll raise selected fees and taxes (e.g., vehicle registration fees, college tuition, fees for state parks, taxes on gambling (casinos, sports betting, and lotteries), tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana), improve revenue collection (including implementing tax amnesty programs), and mitigate fraud risk loss in government benefit programs (especially in benefit programs). Some will refinance outstanding debt obligations, especially in a low-interest environment. Over the long term, they will finance essential capital expenditures with debt to free up cash for the operating budget. They’ll raise rates on major taxes (personal income, sales, and property) and revise their tax codes to reduce or eliminate deductions and exclusions – thereby expanding the taxable base.

SAVING FOR A RAINY DAY

Practically every state government (including the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) has created a budget stabilization fund (BSF, also known as a rainy-day fund (or RDF)). They represent resources explicitly set aside to meet future needs. Many states maintain additional stabilization funds earmarked for specific expenses such as K-12 education (e.g., Idaho’s Public Education Stabilization fund) or disaster relief (e.g., California Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties).

Budget Stabilization Funds (as a Percent of General Fund Revenues)

Most local governments do not have formal rainy-day funds in the same way states do. According to recent research, only 11 of the 30 largest U.S. cities have an actual rainy-day fund. Instead, most localities use unassigned fund balances as informal reserves. However, unlike BSF, unassigned fund balances do not have formal constraints. These informal practices are not necessarily bad, but they’re not as transparent and funds can be drawn down without setting limits or priorities on the use of these funds.

Funding mechanisms for BSF vary from state to state. Most states allow some or all year-end surpluses to flow to their BSFs. Others mandate deposits to the BSF based on a pre-determined formula. Others set aside funds each year through an annual appropriation process until the fund reaches its mandated cap. Research has shown that for governments to accumulate sufficient reserves, they must identify the source of funding using a pre-determined deposit formula and use approval procedures to withdraw funds from the BSF (e.g., meet the definition of emergency or deficit shortfall or require a super-majority vote). There are benefits to having BSFs. Not only do they provide budget flexibility – the reserves can prevent the need for mid-year budget cuts. Additionally, governments with strict deposit and withdrawal rules are more likely to have a higher credit rating and, as a result, incur lower borrowing costs.

BUDGET PROCESS

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

The federal government’s budget process is three processes in one. The president develops and proposes the executive budget, also known as the budget request. In Congress, the House Budget Committee and the Senate Budget Committee pass a budget resolution that identifies the main spending policies and targets for the Congressional side of the budget. The budget resolution allocates budget authority, or the power to incur spending obligations, and budget outlays, or the amount of cash that will flow from the Treasury to a federal agency. The budget authority must be re-authorized each year, even though many programs and services call for budget outlays that will span multiple years. It’s not uncommon for a project to receive budget authority but not receive adequate budget outlays.

The third part of the process is that the House Ways and Means and Senate appropriations committees must pass a series of appropriations bills allowing the rest of the government to spend money. Once the appropriations bills are passed – usually following a lengthy conference committee process – and the President signs them, they become the federal budget.

The basic timeline for the federal budget process was outlined in the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. That process, with the goal of passing the new budget before the end of the federal fiscal year on September 30, is as follows:

The President’s Budget

- October (or shortly after passage of the current fiscal year’s budget): The President’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) works with executive agencies to develop their budget requests for the coming fiscal year. Executive agencies include all the cabinet-level agencies like the Departments of State, Treasury, Justice, and Education, as well as the federal judiciary, independent regulatory agencies, and several other parts of the federal government. OMB reviews the requests and makes changes, subject to the President’s guidance, before combining those requests into the President’s budget.

- February: President submits the budget request, usually concurrent with the State of the Union address. The House and Senate Budget Committees and House and Senate Appropriation Committees, working through their subcommittees, hold hearings and develop appropriation bills that provide funds for agency operations.

Congressional Budget Process – Budget Resolution and Appropriations Process

- March-April: No later than April 15th of each year, the House and Senate Budget Committees draft and manage the passage of their respective budget resolutions. The congressional budget resolution establishes overall revenue and spending totals, allocates spending among major government functions (e.g., national defense, transportation, health, and agriculture), sets limits on resources for discretionary spending programs, and establishes target levels for mandatory spending. Once Budget Committees pass their respective budget resolutions, they go to the House and Senate floors, where they can be amended by majority vote. Representatives from the House and Senate meet in conference to reconcile differences in the House and Senate budget resolutions. The House and Senate then vote on the conference agreement, which, when passed, becomes the congressional budget resolution. Since the congressional budget resolution is an act of Congress, it does not require the President’s signature. Since it does not go to the President, it cannot enact spending or tax law. The congressional budget resolution, therefore, serves as a blueprint for the actual appropriation process and sets targets for other congressional committees that can propose legislation directly.

- May-September: The adopted budget resolution includes a table called the “302(a) allocation” that sets the cap on spending for the appropriations bills. The House and Senate Appropriations Committees each have 12 subcommittees, and each subcommittee crafts an appropriations bill determining the spending authority for the programs under its jurisdiction. The House and Senate pass their appropriations and reconciliation bills. Conference committees resolve differences in the final appropriations and reconciliation bills. The President signs those bills.

- June-July: House and Senate committees prepare reconciliation bills. Reconciliation occurs if Congress needs to legislate policy changes in mandatory spending or tax laws to meet the annual targets laid out in the budget resolution. Said differently, the reconciliation bills implement changes in authorizing legislation, or the laws determining spending on entitlement programs, required by the budget resolution. Most resolution measures are related to entitlement spending like Medicare or to changes in tax law, namely tax cuts.

- October 1: Fiscal year begins.

The Congressional Budget Act of 1974 established the formal rules of the federal budgeting game. However, in the last few decades, the formal budgeting process explains less and less how the federal government spends money. Consider the following:

- If the appropriations bills are not signed into law by October 1, Congress must pass a continuing resolution. This is a temporary measure that extends the existing appropriations bills for a short time, usually 30 to 60 days. Missing the October 1 deadline to enact all 12 appropriation bills is not unusual; in fact, that deadline has not been fully met since FY 1997, and Congress has passed at least one continuing resolution in 16 of the last 20 years. In some years, the government operated on continuing resolutions for most of the next fiscal year.

- For most of the past 20 years, Congress has not passed a budget resolution. Without a resolution, the House and Senate usually pass different substitute versions of the budget targets that would otherwise appear in the budget resolution. Those substitutes or deeming authorization bills are advisory, rather than binding, on the appropriations committees. Said differently, the budget resolution mechanism has not been an effective tool for imposing fiscal discipline.

- At any point during the fiscal year, Congress can impose a rescission that cancels existing budget authority. The Impoundment Control Act of 1974 specifies that the president may propose to Congress that those funds be rescinded. If both Houses have not approved a rescission proposal (by passing legislation) within 45 days of continuous session, any funds being withheld must be made available for obligation. The threat of rescission, and in some cases the actual use of it, has become a way to enforce de facto budget priorities that were never written into the budget resolution or appropriations bills. The best recent example is Congress’s persistent attempts to strip funding for the Affordable Care Act (ACA, more commonly referred to as “Obamacare”).

- In 2011, Congress passed the Budget Control Act (BCA). This law established that unless Congress can reduce the annual budget deficit by a predetermined target, automatic cuts in discretionary and selected entitlement – known broadly as the sequester– will take effect. Unless amended, BCA extends the sequester through 2021. Neither the Budget Act nor any other piece of federal budget legislation makes mention of anything like the sequester. BCA was the latest of many statutory budget caps designed to limit federal government spending automatically. Those caps are not part of the existing budget process framework laid out in the Congressional Budget Act.

- Many of the federal government’s most expensive activities are now paid for outside the budget process. The best recent example is the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. By some estimates, the two wars cost $1-3 trillion or somewhere between $2,000 and $10,000 for every US taxpayer. Congress appropriated around $50 billion for “The Surge” of US troops into Iraq as part of the FY2006 Defense Department Appropriations bill. The remainder of the funding was allocated through supplemental appropriations and budget amendments. Supplemental appropriations are appropriations bills that add to an existing appropriation. They are designed to provide resources for unexpected emergencies, such as disaster relief after a hurricane or earthquake. Budget amendments are changes to budget outlays to that same effect. Most of these supplemental/emergency appropriations were financed with debt.

SUPPLEMENTAL APPROPRIATIONS AND THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC

Since March 6, 2020, lawmakers have enacted four laws in response to the pandemic – The Families First Coronavirus Act (March 18, 2020 – $192 billion), The Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security Act (March 27, 2020 – $1.7 trillion), the Paycheck Protection Program and Healthcare Enhancement Act (April 24, 2020 – $483 billion), the Consolidated Appropriations Act (December 27, 2020 – $900 billion), and the American Rescue Plan (March 11, 2021 – $1.9 trillion). The five appropriation bills increased federal government outlays by $5.2 trillion.

For context, following the start of the Great Recession, Congress approved three major pieces of legislation, including the Economic Stimulus Act (February 2008 – $151.7 billion), the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act that created the Troubled Asset Relief Program (October 2008 – $700 billion; TARP recovered $443 billion), and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (February 2009 – $840 billion).

- Since roughly 1990, Congress has used budget reconciliation to pass several major pieces of legislation, including the “Bush tax cuts,” the Medicare prescription drug benefit (“Part D”), and the Affordable Care Act. Reconciliation is a powerful tool because, by Senate rules, reconciliation bills are not subject to filibuster. A filibuster is when an individual Senator kills a proposed bill by “talking it to death,” taking advantage of Senate rules allowing unlimited debate. To end a filibuster, the Senate must invoke cloture with a two-thirds majority vote of all Senators. Given the highly partisan character of the Senate throughout the past few decades, the threat of a filibuster is always present, which imposes a de facto two-thirds majority to approve virtually every piece of legislation proposed in the Senate.

BUDGET PROCESS

NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

Unlike governments, non-profits are not required to prepare or adopt a budget prior to the start of the fiscal year (they are required to prepare audited financial statements and file with the Internal Revenue Service tax form 990 at the end of the fiscal year or tax year). Non-profits must therefore be internally motivated to prepare, review, and adopt a balanced operating budget – even though no requirements exist in law. Moreover, the adopted budget should become an unwavering policy guiding the organization throughout the budget period.

Non-profits’ budgets should reflect the organization’s priorities as outlined in their strategic plan. The non-profit board serves as the organization’s governing body with responsibility and oversight of mission, leadership, and finances. While budgets are prepared by program managers together with finance officers and the chief executive, the non-profit board retains the ultimate responsibility of not only setting the organization’s strategic direction but also ensuring that there are adequate resources to execute the strategic plan.

The chief executive, together with the finance director, will outline priorities as stated in the organization’s strategic plan and given the uncertainty in the external operating environment (e.g., changes in federal or state laws or funding priorities, volatility in the market, and changes in contributions). Having prepared their program budgets, program managers must defend their proposals in a budget review meeting with the chief executive and the finance director. Following an amendment process, the finance director will merge the program budgets, incorporate administrative and overhead costs, and prepare a complete budget proposal for the board to consider.

Most non-profits prepare their operating budgets on a cash basis. Budgets prepared on a cash basis emphasize when cash is received or paid. Budgets prepared on an accrual basis shift the focus away from cash inflows instead of focusing on when revenues are earned and expenses accrued. Does this matter? Absolutely! If the organization is budgeting on a cash basis, expenses that do not result in a cash outflow (e.g., depreciation) would not be included in the budget – even though the expenses represent a real cost for the organization.

While the operating budget represents the organization’s priorities for the budget period, non-profits that require capital investments to execute their business model (e.g., universities, museums, and hospitals) frequently consider their capital spending priorities separately from their operating budget. Why? Well, a couple of considerations are important. First, most non-profits finance capital expenditures with non-operating revenues (e.g., proceeds from a capital campaign, accumulated unrestricted reserves, or long-term debt). Second, an assessment of project viability is necessary, as capital investments should provide a return (or, at the very least, cover initial investment costs). Therefore, an assessment of project viability would be prudent. This process requires a different set of analytical tools (e.g., net present value analysis and annual cash flow forecast). Finally, the budget period for capital expenditures is irrelevant, as the focus shifts towards the asset’s useful life (e.g., 30 years for buildings).

The (operating and capital) budget review and approval process will be contingent upon the size of the organization’s budget, the number of board members, and the board committee structure. The review process frequently begins with a budget presentation to a finance committee. The finance committee pays special attention to the long-term fiscal implications of the proposed spending priorities given current revenue streams. Having approved the budget, an executive committee (made up of board officers and chairs of various committees) reviews and approves the budget, after which it is presented to the entire board for final approval. Once approved, the finance director should report, on a quarterly (or monthly) basis, year-to-date spending, budget versus actual reports (with variance analysis), working capital cash balances, and key changes in programs or policies that affect the operating budget.

“CREATING” BUDGET BALANCE

One of the main criticisms of state and local budgets is that “balanced budgets” might actually hide structural deficits. There are two reasons for this. First, most governments prepare their budgets on a cash basis rather than an accrual basis. Differences in timing and recognition of revenues or expenses mask the long-term effects of budget decisions. Second, managers and policymakers can employ various tactics to create a “phantom” balanced budget.

The pressure to present a balanced budget results in the frequent use of budget gimmicks. Gimmickry can be defined as a practice that intentionally violates accounting rules, budgeting norms, or legal requirements meant to ensure fiscal prudence. They are used to hide program costs, revenue shortfalls, projected deficits, or bypass formal budget process requirements (e.g., adopt a balanced budget).

The temptation of the quick fix has seduced just about every lawmaker. They include:

-

Use of unrealistic budget assumptions. Use of overly optimistic assumptions that result in revenue projections far exceeding the economic reality, masking the size and magnitude of the government’s structural deficit and growth in long-term obligations (e.g., federal debt or unfunded pension obligations).

-

Inter-fund transfers and fund sweeps. The transfer of resources in and out of funds just before or after budget approval to present a balanced budget.

-

Use of one-time revenues. State and local governments have used proceeds from asset sales, privatizations, and contract arrangements to balance the current period budget – even though budgets for the out-years remain unbalanced.

-

Accelerating revenue collection. This changes when revenues are recognized, which can change the budget balance’s complexion in a given fiscal period.

-

Putting off payments or ignoring known costs. Preparing budgets on a cash basis means costs incurred in the current year that are due in a future period are not included in the current budget. When governments offer pension and OPEB benefits but fail to make the contributions necessary to meet future costs, they are essentially borrowing from their future taxpayers.

-

Keeping off the record. Shift spending to off-budget entities (OBEs) that issue non-guaranteed debt backed primarily with non-tax revenues and are beyond the control and scrutiny of taxpayers.

-

Delaying intergovernmental payments. This is a common tactic because governments have limited ability to collect revenues from each other.

-

Counting on revenues or savings that are unlikely to materialize – the “Magic Asterisk.” Resources to cover the new spending would come from vaguely described efficiency gains in existing programs. Programs expected to produce those new resources were identified with an asterisk in President Reagan’s budgets, hence the name “Magic Asterisk.”

“Using proceeds from the sale of government assets as revenues to cover operating costs and thinking you have made the public better off is about the same as burning pieces of your house for heat and thinking that you are better off because you haven’t had to buy firewood. ”

John Mikesell (2011) “Fiscal Administration: Analysis and Application for the Public Sector”

BUDGET POLITICS

Within the formal budget process, there are budget politics. For most public managers, the politics and strategy of making a budget are just as important, if not more important, than the formal budget process. Here we briefly discuss some of the most common budget-making strategies. Some of these strategies are more appropriate if the goal is to limit spending, while others are more appropriate if a department or agency wants to expand programs, or at the very least maintain the status quo. They include:

- Cultivate a clientele. Effective public managers understand who “uses” and who “benefits” from their programs and services. They also understand that those users are the best advocates for a program. This is especially true for programs that benefit children, the disabled, and other vulnerable populations. A simple anecdote about a program from one of its clients can be exponentially more powerful than a well-done differential cost analysis.

- Make friends with legislators. Legislators are much more likely to support a program when they understand that program and who benefits from it. This is particularly true when that program benefits its constituents, and when the legislators played a role in creating, expanding, or protecting it. Of course, this strategy comes with risks. Governors, mayors, and other executives often try to limit department heads’ and program managers’ access to legislators to prevent staff relationships with legislators that might undermine their own budget priorities.

- “Round it Up.” This is especially true on the spending side. Rounding up caseloads, spending estimates, interest expenses, and other costs will expand the budget authority and, if actual spending falls short of budgeted spending, create an end-of-year “surplus.” The risk is that persistent over-budgeting for spending can undermine a budget maker’s credibility.

- “We have a crisis.” Some managers like to project that major revenue shortfalls or spending cuts are imminent, even if they aren’t. Staff who believe they might face difficult budget cuts are more likely to manage their programs with careful attention to spending discipline and timely collection of revenues. Of course, this can also lead to staff burn-out and ruin a manager’s credibility if said crisis never happens.

A few strategies are most effective when a manager is asked to trim their budget.

- “Across-the-Board.” Some managers prefer to respond to budget cuts by cutting all their programs equally, or “across the board” (ATB). To staff, ATB cuts appear fair, transparent, and simple. Cutting all programs equally assumes those programs have identical cost structures, current staff openings, and the capacity to generate revenues. That’s rarely true. The result is that ATB often affects different programs and services in quite different ways, even though the intent is to bring about a uniform impact. Sometimes those differential effects can themselves be valuable to managers.

- “Do Nothing.” An unchanged budget is, in effect, a budget cut. If a program is given no new resources it must find other ways to address cost inflation, growth in caseloads, staff cost of living adjustments, and other growth in spending. Sophisticated managers argue, often successfully, that a “steady state” budget (i.e., no new resources, but no cuts) is a fair way to take a budget cut.

- Lean on precedent. In a cutback environment, what happened in the past can be a powerful tool for managers. No manager wants to have to choose how to cut his or her program. But if they can say, “I didn’t really choose these cuts; we’re just following past precedent,” they’re afforded some degree of political cover. Whether past precedent really dictated those cuts, or whether there even is a past precedent, is often debatable.

- “It’s essential for public safety.” Managers can try to position their program as vital to public health or safety. Sometimes these connections are obtuse, at best. For instance, during the Great Recession, many local libraries protested cuts to library hours by pointing out that libraries are a safe and supportive gathering place for teenagers. Unsupervised teenagers roaming the streets would create, they argued, a serious public safety concern.

- Propose a study. Public organizations can rarely predict – or so they say – exactly how a budget cut will affect their clients, staff, and overall mission. So, in response to a cut, managers routinely propose to “study the issue.” A study allows for more time to either identify potential cuts or for the political or economic environment to shift in ways that will obviate the need for a cut at all.

- “Cut the main artery.” One way to respond to a requested cut is to cut the largest program that’s most central to your mission (i.e. the “main artery”). Cutting that program is, in effect, threatening to cripple your program. Some policymakers will respond with a request for a smaller cut or a cut to a less mission-centric program. The danger here is what happens if policymakers agree to allow a manager to cut the main artery.

- “Just take the whole thing.” If a program was cut recently, managers can take the request for an additional cut as an opportunity to offer to end the program. They’ll ask: “We’ve already been cut to the bone, so what’s the point of staying open?” or something to that effect. Whether additional cuts would really harm the program is often incidental to the argument.

- “You pick.” Instead of proposing cuts, offer policymakers a range of options and ask them to decide which option the program should pursue. Like with “lean on precedent,” this allows managers to avoid direct responsibility for specific cuts to his or her staff and other resources. This strategy is prone to backfire when policymakers respond by saying, “It’s not my job to pick. You know your program better than anyone. You pick.”

- “Washington Monument.” In 1994, the federal government shut down after President Clinton and House Speaker Gingrich could not agree on a continuing resolution. President Clinton responded by ordering the National Park Service to close all of the key historic sites in Washington, D.C. One of the first to close was the Washington Monument. As the shutdown dragged on, President Clinton was able to frame the closed Washington Monument as a symbol of Congressional intransigence. The essence of the Washington Monument strategy is to propose cuts to a small but highly visible program.

And finally, managers often deploy a different set of strategies when attempting to expand their program’s budget:

- “It pays for itself.” Managers can sometimes argue that investing in a program will “pay for itself” through cost savings later. For instance, public health advocates have long argued that expanding childhood immunization programs pays for itself by reducing the incidence of communicable diseases like tuberculosis, measles, and rubella that place enormous strain and expense on public hospitals.

- “Spend to save.” Investments in technology, equipment, and infrastructure can save staff time, reduce paperwork, collect revenues faster, etc. – or that’s how managers sell those investments in the budget process.

- “Foot in the Door.” Many large, long-standing, popular public sector programs began small. An effective way to expand a program is to run a small pilot program, study, or demonstration project. Legislators and board members are generally willing to appropriate small amounts of money to try “innovative” approaches. With time, many of those small experiments morph into large-scale programs.

- “It’s just temporary.” Like “small innovations,” legislators and board members are much more willing to provide temporary funding for a program or project than they are to provide permanent funding or budget authority. Crafty managers are able to convert temporary funding into either “ongoing temporary funding” or even permanent authority.

- “Finish what we started.” This approach is especially popular with respect to capital projects. Many capital projects begin with an appropriation to analyze, plan, and design a capital project. With that planning in place, managers can make a compelling argument that it’s necessary to appropriate more money to “finish what we started,” often without regard for whether the plans are complete or whether the analysis suggests the project is necessary.

- “Re-categorize.” Sometimes shifting a program to a different part of the budget is a necessary step toward expansion. For example, public health advocates have successfully argued that many public health activities like smoking cessation or diabetes prevention are in fact education or outreach programs. Within the education budget, they have access to a much wider range of funding sources and constituent champions. We’ve seen a similar dynamic with homeland security. Many programs in areas like crime prevention and cybersecurity were once local public safety initiatives but have since migrated to far more lucrative state and federal homeland security budgets.