IV. Empowerment, Safety, and Trust

Empowerment, safety, and trust

Libraries should be safe spaces where patrons feel empowered to explore information and resources without fear of judgment or harm. Librarians play a crucial role in fostering this sense of safety and trust through trauma informed practices by offering non-judgmental support and recognizing when patrons are feeling activated. By promoting empowerment, librarians help patrons regain a sense of control over their own information-seeking process, which is especially important for individuals who have experienced trauma.

Antiracist and anti-ableist practices prioritize the empowerment and safety of marginalized communities. Librarians can promote empowerment by providing resources and services that address the specific needs of patrons who have experienced racism or ableism. Creating a safe and trusting environment allows patrons to access library resources without fear of discrimination or harm.

Promotion of empowerment, safety, and trust in libraries involves empowering patrons to make informed decisions about their library use and ensuring that library spaces are safe and welcoming for all. Librarians work to build trust with patrons by respecting their autonomy and confidentiality and providing a supportive environment where they feel valued and respected. Promotion of empowerment, safety, and trust is vital for trauma-informed librarianship to create an environment where patrons feel empowered to access library services and resources without fear of judgment or harm. Librarians play a crucial role in promoting a sense of safety and trust by actively listening to patrons, respecting their autonomy and boundaries, and empowering them to make informed choices about their use of library services. By fostering a culture of empowerment, safety, and trust, librarians can help trauma survivors feel supported and respected in their journey towards healing and recovery. Here’s how Empowerment, safety, and trust relates to each of the principles:

- Safety: The Promotion of empowerment, safety, and trust directly contributes to ensuring safety within the library environment. By empowering individuals to take an active role in their own safety and well-being, librarians create a sense of agency and autonomy among patrons. This empowerment may include providing information about safety protocols, resources for crisis intervention, and promoting awareness of personal boundaries. Additionally, fostering a culture of trust and support encourages patrons to feel safe and secure within the library space, knowing that their needs are valued and respected.

- Trustworthiness & transparency: The promotion of empowerment, safety, and trust is inherently linked to trustworthiness and transparency within the library community. By promoting open communication, honesty, and accountability, librarians build trust with patrons, demonstrating a commitment to their well-being and safety. Transparent policies and procedures related to safety measures and emergency protocols further enhance trust, ensuring that patrons feel informed and reassured about their safety within the library environment.

- Peer support: Empowering individuals to prioritize their safety and well-being fosters a supportive environment conducive to peer support. When patrons feel empowered to seek assistance and support from their peers, librarians play a vital role in facilitating connections and fostering a sense of community within the library. Promoting empowerment through peer support initiatives encourages individuals to look out for one another, offering assistance and encouragement when needed, and creating a network of mutual support that enhances overall safety and well-being.

- Collaboration & mutuality: The promotion of empowerment, safety, and trust encourages collaboration and mutuality among library staff and patrons. By empowering individuals to actively participate in safety initiatives and decision-making processes, librarians foster a sense of ownership and shared responsibility for safety within the library community. Collaborative efforts to identify and address safety concerns, as well as mutual support networks, strengthen bonds among staff and patrons, creating a culture of collective care and solidarity.

- Empowerment, voice, & choice: The promotion of empowerment, safety, and trust emphasizes the importance of empowering individuals to make informed choices about their safety and well-being. Librarians provide patrons with access to information, resources, and support services, empowering them to make decisions that align with their needs and preferences. Encouraging empowerment and choice promotes a sense of autonomy and self-determination, enabling individuals to take proactive steps to ensure their safety within the library environment.

- Cultural, historical, & gender issues: The promotion of empowerment, safety, and trust should be sensitive to cultural, historical, and gender factors that influence individuals’ experiences of safety and well-being. Librarians recognize and respect diverse cultural practices, historical traumas, and gender identities, ensuring that safety initiatives are inclusive and equitable for all patrons. By addressing cultural and gender-specific safety concerns and promoting culturally responsive approaches to safety and trust-building, librarians create an environment that is welcoming, inclusive, and supportive of diverse identities and experiences.

Empowerment, safety, and trust are often inherent in the ethos of librarianship, making them relatively easy to adopt as trauma informed librarianship principles. These values are deeply ingrained in the profession and reflect the foundational principles of librarianship, making them natural extensions of library services and interactions:

- Empowerment: Libraries empower individuals by providing access to information, resources, and opportunities for learning and personal growth. Through access to knowledge and educational resources, patrons are empowered to pursue their interests, achieve their goals, and make informed decisions. Library staff play a crucial role in empowering patrons by offering guidance, support, and encouragement to help them navigate the vast array of resources available to them.

- Safety: Libraries aim to serve as safe spaces where individuals can explore ideas, express themselves freely, and engage with information without fear of judgment, discrimination, or censorship. Creating a physically and emotionally safe environment is essential for fostering a sense of belonging and well-being among patrons. Librarians work to ensure that library spaces are welcoming, inclusive, and free from harassment or intimidation, allowing patrons to feel comfortable and secure as they access library resources and services.

- Trust: Trust is built through transparency, reliability, and integrity in library services and interactions. Patrons trust libraries to provide accurate and reliable information, protect their privacy and confidentiality, and uphold their rights to access information freely. Librarians cultivate trust by demonstrating cultural humility, respect, and empathy in their interactions with patrons, and by actively listening to their needs and concerns. Building trust enables patrons to feel confident in seeking assistance from library staff, accessing library resources, and engaging with library services, ultimately enhancing their overall library experience.

In the realm of library services, the principle of promoting empowerment, safety, and trust stands as a cornerstone of trauma-informed librarianship. This principle underscores the commitment of libraries to create environments that prioritize the well-being and agency of all patrons, especially those who have experienced trauma. By fostering empowerment, safety, and trust, libraries aim to provide a nurturing and inclusive space where individuals feel respected, supported, and empowered to engage with library resources and services. This introduction explores the significance of promoting empowerment, safety, and trust in trauma-informed librarianship and examines how these principles contribute to the overall mission of libraries as community-centered institutions dedicated to serving diverse populations with empathy and compassion.

Trauma informed librarianship in praxis

Learning to de-escalate situations is vital in trauma-informed librarianship. Central to trauma-informed care is the recognition that an individual’s experience determines the impact of an event on their well-being. Library staff must acknowledge and validate patrons’ perspectives on what they find traumatic, fostering an environment of trust and understanding. When applying trauma-informed strategies in libraries, it’s also important to consider contextual factors influencing patron behavior (such as income, housing, and involvement with the justice system). This helps us meet our goal of creating safe and consistent spaces that validate patrons’ experiences.[1]

Recognizing the signs of distress is incredibly important for effective de-escalation. Patrons may exhibit various indicators such as anger, fear, depression, or difficulty concentrating. Understanding the concept of the “window of tolerance” can provide valuable insight into these signs. The window of tolerance refers to the optimal zone where individuals can effectively cope with stressors and maintain emotional regulation. When patrons exceed their window of tolerance, they may display heightened emotional reactions and struggle to manage their responses effectively. By recognizing the signs of distress and understanding what the window of tolerance is, library staff can take care of themselves and implement de-escalation strategies to promote safety and support within the library environment.[2][3][4]

There are many techniques and strategies available for implementing de-escalation effectively. We have already touched on some of these approaches—active listening, nonviolent communication, flexible communication. In this chapter, we will add to these mindful approaches, focusing on respecting personal space, being aware of body language, offering choices, asking open-ended questions, regulating your emotions, and understanding your limits. Implementing de-escalation strategies helps prevent the need for resorting to punitive measures. This furthers the library as a safe and trustworthy space where patrons are empowered to regain a sense of control and autonomy. By giving patrons space to express their needs and preferences, library staff create a culture of respect and dignity within their community.

Empowerment Exercise

Create a list of scenarios that commonly occur in the library, such as asking for assistance finding a book or using a computer. For each scenario, brainstorm multiple ways to empower patrons by offering them choices and autonomy. Role-play these scenarios with a colleague or record yourself practicing open, empathetic, and flexible communication communication techniques.

The Window of Tolerance

What is the window of tolerance?

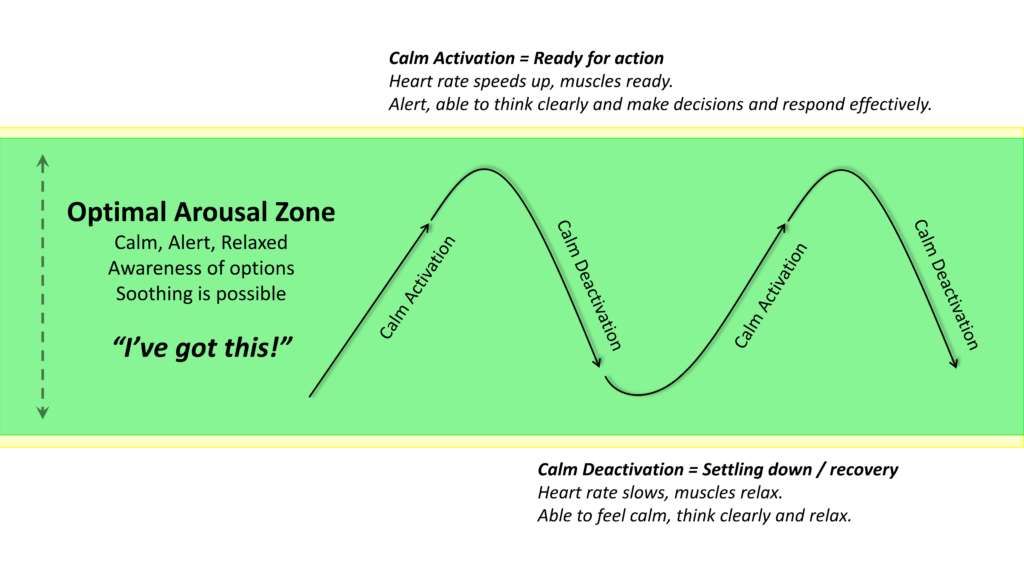

The concept of the “window of tolerance” originates from the field of trauma psychology and refers to the optimal state of arousal in which individuals can effectively cope with stressors and regulate their emotions. In this zone, people can function the most effectively— individuals can engage in problem-solving, decision-making, and relational interactions with relative ease.Within this window, individuals feel calm, focused, and capable of managing life’s challenges without becoming overwhelmed.[5]

When we are within our window of tolerance, we are essentially in our optimal zone for functioning. Our nervous system is regulated, so it is easier for us to adapt and respond to stress and regulate our emotions. In this window, we have the capacity to be flexible, communicate well, cope with daily stressors, build healthy relationships, and regulate our emotions.[6]

Factors that impact our Window of Tolerance

- Physical or sexual abuse

- Neglect

- ACE’s

- Frequently not feeling heard or seen

- Having your emotions frequently dismissed or invalidated by others

- Lack of support in relationships

- Chronic stress in work or home environments

- Being without basic needs: food, water, housing, social support

- Sleep deprivation or exhaustion

Trauma and its impact on our window of tolerance

Understanding the impact of trauma on the Window of Tolerance is crucial in recognizing how disruptive experiences can shift one’s emotional equilibrium and sense of safety. When individuals experience trauma (especially if they have experiences complex trauma, which is characterized by sever and ongoing neglect, abuse, assault, violence, racism, etc), it disrupts their emotional equilibrium and sense of safety, and as a result, their Window of Tolerance is often smaller than those who have not had as many adverse experiences. This means that disruptions that may seem minor can push them beyond their Window of Tolerance, triggering survival mode in their nervous system. This is because most of their time and energy are spent striving to feel safe, and they lack the energy to face other life stressors.[7][8]

“Experiencing complex trauma can overwhelm your window of tolerance repetitively and across time” — Brian Jo, PhD[9]

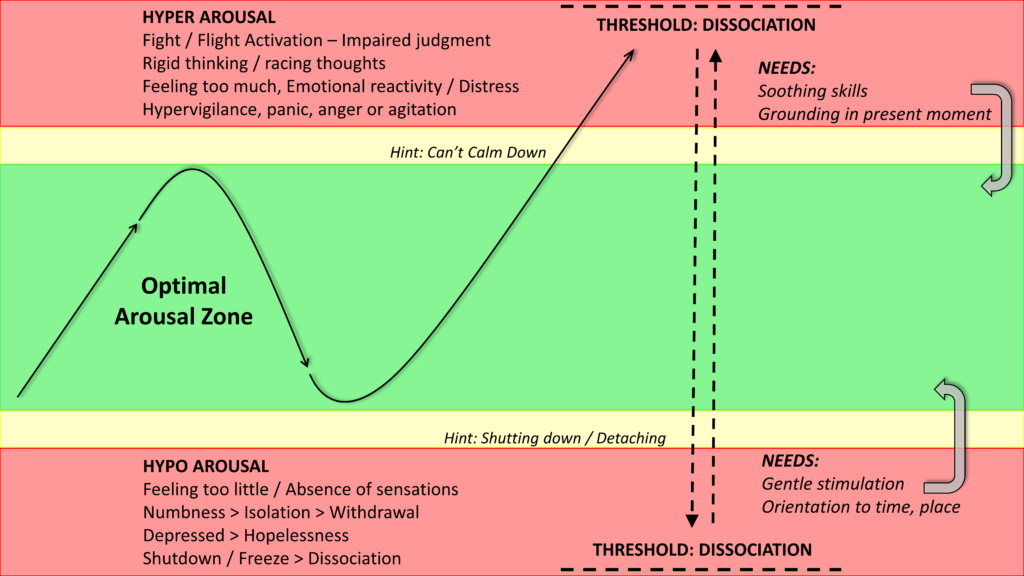

When pushed beyond this threshold, absorbing new information becomes challenging and people experience feelings of overwhelm (hyperarousal) or shutdown (hypoarousal). Hyperarousal occurs when individuals become overwhelmed by intense emotions such as fear, anger, or anxiety, leading to heightened physiological arousal and a sense of being “flooded” by emotions. In this state, individuals may exhibit impulsive or reactive behaviors, have difficulty concentrating, and struggle to regulate their emotions effectively. On the other hand, hypoarousal involves a state of numbness, withdrawal, depression, where individuals may feel detached from their emotions, experience a sense of emptiness or disconnection, and have difficulty engaging with their surroundings or forming meaningful connections with others.[10][11]

This chart provides a direct comparison between hyperarousal and hypoarousal, highlighting their distinct characteristics side by side:[12][13][14]

| Hyperarousal | Hypoarousal |

| Increased heart rate: You may notice your heart pounding, racing, or even skipping beats. It feels like your heart is working overtime to keep up with the intense sensations coursing through your body. | Feeling emotionally numb: You may find it challenging to experience or express emotions. It’s as if a protective barrier has been put up, dulling your ability to engage with your feelings fully. |

| Physical tension: Your body feels tight and tense. Your muscles may be constantly clenched, leading to headaches, jaw pain, or backaches. | Fatigue and lack of energy: Hypo-arousal can drain your energy levels, leaving you feeling constantly tired or unmotivated. You may struggle to find the drive to engage in daily activities or pursue hobbies you once enjoyed. |

| Difficulty sleeping: When in a state of hyper-arousal, it becomes challenging to relax and fall asleep. Your mind is constantly on high alert, making it hard to wind down and get the rest you need. | Difficulty concentrating: Your ability to focus and concentrate may be impaired in a state of hypo-arousal. Staying engaged in tasks or conversations becomes challenging, decreasing productivity and performance. |

| Hypervigilance: Your senses may become hyper-sensitive, causing you to feel easily startled or overwhelmed by sensory stimuli. You might find yourself constantly scanning your surroundings for potential threats. | Memory problems: Hypo-arousal can impact your memory, making recalling important details or events difficult. You may forget things more frequently or struggle to retain new information. |

| Irritability and anger: Hyper-arousal often goes hand in hand with heightened emotions, particularly irritability and anger. Small triggers can set off intense emotional outbursts, leaving you feeling out of control. | Feeling disconnected from others: The emotional disconnection brought on by hypo-arousal can make it challenging to form or maintain meaningful connections with others. It may feel like you are observing life from a distance rather than actively participating. |

| Racing thoughts: Your mind may feel chaotic, with thoughts racing rapidly. Focusing or concentrating on tasks becomes challenging, as your attention is constantly pulled in different directions. | Lack of motivation: Hypo-arousal can zap your motivation and enthusiasm for life. Finding enjoyment in activities or setting goals for yourself becomes difficult, leading to a sense of stagnation or feeling stuck. |

If we get too far out of our window of tolerance on both ends (experiencing excessive hyperarousal or hypoarousal), we can experience dissociation. Simply put, “Dissociation occurs in response to extreme arousal states and/or extreme stress, as a protective mechanism to shield us from further physical, psychological, or emotional harm. Dissociation is essentially a disconnection from our conscious awareness (i.e., thoughts, memories, feelings, voluntary actions) and our sense of ‘Self’.” [15]

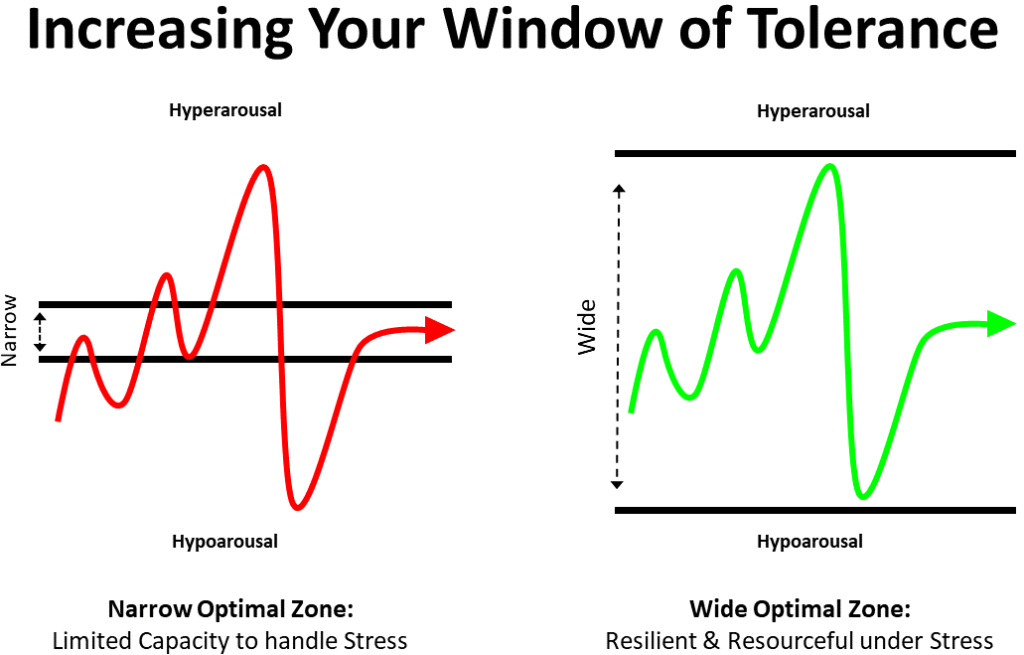

If you frequently go back and forth between hypoarousal and hyperarousal, experience great difficulty in coping with stressors, or feel like there is a very narrow range where emotions feel comfortable and manageable, you likely have a narrow Window of Tolerance.[16] However, there are things you can do to get you back within and help you expand your Window of Tolerance.

Understanding your Window of Tolerance

“You can heal and expand your Window of Tolerance by restoring your capacity to integrate your experiences and be present in the moment.” — Brian Jo, PhD In short, there are two key ways that can help you understand your window of tolerance:

- Pay attention to your triggers: Identify the experiences, situations, words, etc that activate you and send you to the edge of your Window of Tolerance.

- Be mindful of your reactions: Be present in your body and observe how your body is reacting to these triggers. By being present in your body and paying attention to your emotions and bodily sensations, you can increase your capacity to mindfully observe your experiences and learn to regulate your arousal states

Increasing your window of tolerance[17][18][19]

More specifically, there are some strategies you can use to help you:

- Somatic experiencing: Dance, yoga, breathing exercises, mindfulness, body awareness, grounding can all help you reconnect to your body and increase your window of tolerance. When we are in a state of hypo or hyperarousal, we are overwhelmed and become disconnected with our body. When this happens to an extreme, we disassociate. Moving our body, connecting to our breath, noticing the sensations we are feeling can all help us increased our window of tolerance.

- Connecting with supportive communities: Creating secure, genuine, and nurturing relationships can help you co-regulate your emotions and expand your Window of Tolerance. Receiving support from friends, family members, chosen family is crucial to expanding your window because when you feel seen, heard, affirmed, and validated, it reduces feelings of isolation, making space for you to navigate difficult situations. Support groups can also be extremely beneficial, as it can be incredibly validating to talk to people who have had similar experiences and share experience, resources, and advice. You cannot heal is isolation.

- Seeking professional help: Working with a trauma-informed therapist is essential. They can provide you direct support and specific strategies to help you with your unique needs.

How to get back within your window[20][21]

Strategies for hyperarousal

- Breathing exercises: deep breathing, box breathing, and cyclic sighing can help counter hyperarousal by calming your heart rate, restoring regular breathing, and reducing anxiety.

- Relaxation techniques: Doing a progressive muscle relaxation or a relaxing visualization exercise can also help you manage your reaction to a stressor.You can also use a foam roller or yoga ball to loosen areas of muscular tension and bring you back into the present moment using your body.

- Purposeful movements: Stretching, yoga, or rhythmical movements (like dancing or swaying) can offer soothing benefits, while activities like shaking, stomping, or vigorous exercise provide an outlet to burn off excess energy.

- Engaging your senses: Taking a hot shower, splashing cold water on your face or taking an ice bath, eating comfort food (hot chocolate or something chewy but smooth), lying under a weighted blanket, listening to soothing music.

Strategies for hypoarousal

- Sensory stimulation: anything that you can do mindfully while engaging your 5 Senses could be helpful— smelling essential oils, chewy crunchy food, cold water immersion, holding a piece of ice until it melts, 5-4-3-2-1:Name five things you can see, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. This exercise engages your senses and helps redirect your attention to your immediate environment.

- Physical activity: Engage in vigorous exercise that challenges your coordination and stamina, such as attempting a handstand against a wall or walking backward for three minutes on your hands and feet with your belly facing upward.

- Body scan: Begin by directing your awareness to your toes and progress upward, attentively observing each part of your body. Take note of any sensations, tension, or relaxation you experience in each area. This exercise facilitates a connection with your physical sensations and grounds you in the present moment.

- Reach out to a friend for meaningful connection.

Keeping a journal to track triggers and physiological reactions, along with noting effective grounding techniques, can aid in regulating emotions and returning to your window of tolerance. For certain people, such as those with a narrow Window of Tolerance (which is understandably common in people who have experienced significant traumas or stress), there can be almost zero warning that they are entering either Hyper- or Hypo-arousal. This is not their fault. Rather, it is the result of the trauma, and how trauma affects our brains – it makes the brain over-protective to prevent any further harm.

However, unfortunately, this can sometimes take people by surprise and they can lash out at others (‘attack’) or themselves, or can completely shut-down (‘withdraw’), and this may leave a person feeling ashamed, or powerless and out of control of their emotions. If this is the case (if this is you, or someone that you care about), please understand that self-help techniques alone will likely only be of limited use. When this is the case, consulting with an experienced, trauma-informed clinical psychologist is highly recommended.

The goal of trauma therapy and resilience-building practices is to help individuals expand their window of tolerance, allowing them to tolerate a wider range of emotional and physiological experiences without becoming overwhelmed or dissociated. Through techniques such as mindfulness, grounding exercises, emotional regulation strategies, and trauma processing therapies, individuals can gradually increase their capacity to navigate stressors and regulate their emotions within the optimal zone of the window of tolerance. By expanding their window of tolerance, individuals can enhance their resilience, improve their emotional well-being, and foster healthier relationships and coping strategies in the face of adversity.

Safe Space Audit

Take a walk through the library and assess the physical environment from the perspective of a patron who may have experienced trauma. Identify areas that could be improved to create a safer and more welcoming space, such as adding more comfortable seating, adjusting lighting levels, or providing privacy screens.

De- escalation

Now that you understand the Window of Tolerance and how to support individuals in hypo or hyperarousal states, we can delve into de-escalation techniques, transitioning from understanding the why to exploring the how.

De-escalation is one technique that can be used when confronted with violent or aggressive behavior. De-escalation is “transferring your sense of calm and genuine interest in what the patient wants to tell you by using respectful, clear, limit setting [boundaries],” and the goal is to “build rapid rapport and sense of connection with an agitated person.”[22]

De-escalation is a proactive approach aimed at averting potential violence. It involves deliberate actions, effective communication, and nuanced body language to diffuse tense situations. Before you begin de- escalation, it is important to check in with yourself and see if you have the capacity to engage with this situation. If for whatever reason you feel like you cannot engage with the patron in a kind and empathetic manner, it is important to remove yourself and seek help from another staff member. If you cannot remain calm at that time, you cannot effectively de- escalate the situation. You will likely inadvertantly activate the patron further and make the situation worse. Overall, purposeful actions in de-escalation involve thoughtful and deliberate responses aimed at diffusing tension, promoting safety, and fostering positive communication and outcomes.

Quick tips for de- escalation

- Identify who you are

- Identify your purpose

For example, you could say, “I’m a library worker, and I’m here to help you get what you need.” From here, you can use active listening techniques and nonviolent communication. Depending on the situation, you can ask the patron what they need (What has helped you in the past?) or offer suggestions (Would you like to take a deep breath with me? Would you like to sit in a private room and collect your thoughts?). If the patron remains activated and asks challenging (or accusatory, aggressive, or attacking) questions, ignore what they said without ignored them. Try and bring their focus back on how you can help them by offering empathy while establishing boundaries. You can say something like, “I understand it’s confusing when rules change. The library changed this policy, and it’s really frustrating.” This avoids personalization and positions you as an ally, instead blaming the institution and institutional policies.

Remember, the goal of de- escalation is to calm the patron down, not solve the problem that caused the agitation. If you can solve their problem, that is great, but most of the time this agitation has nothing to do with you and the library. Most of these situations are due to poor timing and outside factors.

A deeper dive into de- escalation

Crisis Prevention Institute’s top 10 de- escalation tips:[28]

- Be empathetic and nonjudgemental: When someone says or does something you perceive as weird or irrational, try not to judge or discount their feelings. Whether or not you think those feelings are justified, they’re real to the other person. Pay attention to them. Keep in mind that whatever the person is going through, it may be the most important thing in their life at the moment.

- Respect personal space: If possible, stand 1.5 to three feet away from a person who’s escalating. Allowing personal space tends to decrease a person’s anxiety and can help you prevent acting-out behavior. If you must enter someone’s personal space to provide care, explain your actions so the person feels less confused and frightened.

- Use nonthreatening nonverbals: The more a person loses control, the less they hear your words—and the more they react to your nonverbal communication. Be mindful of your gestures, facial expressions, movements, and tone of voice. Keeping your tone and body language neutral will go a long way toward defusing a situation.

- Avoid overreacting: Remain calm, rational, and professional. While you can’t control the person’s behavior, how you respond to their behavior will have a direct effect on whether the situation escalates or defuses. Positive thoughts like “I can handle this” and “I know what to do” will help you maintain your own rationality and calm the person down.

- Focus on feelings: Facts are important, but how a person feels is the heart of the matter. Yet some people have trouble identifying how they feel about what’s happening to them. Watch and listen carefully for the person’s real message. Try saying something like “That must be scary.” Supportive words like these will let the person know that you understand what’s happening—and you may get a positive response.

- Ignore challenging questions: Answering challenging questions often results in a power struggle. When a person challenges your authority, redirect their attention to the issue at hand. Ignore the challenge, but not the person. Bring their focus back to how you can work together to solve the problem.

- Set limits: If a person’s behavior is belligerent, defensive, or disruptive, give them clear, simple, and enforceable limits. Offer concise and respectful choices and consequences. A person who’s upset may not be able to focus on everything you say. Be clear, speak simply, and offer the positive choice first.

- Choose wisely what you insist upon: It’s important to be thoughtful in deciding which rules are negotiable and which are not. For example, if a person doesn’t want to shower in the morning, can you allow them to choose the time of day that feels best for them? If you can offer a person options and flexibility, you may be able to avoid unnecessary altercations.

- Allow silence for reflection: We’ve all experienced awkward silences. While it may seem counterintuitive to let moments of silence occur, sometimes it’s the best choice. It can give a person a chance to reflect on what’s happening, and how he or she needs to proceed. Believe it or not, silence can be a powerful communication tool.

- Allow time for decisions: When a person is upset, they may not be able to think clearly. Give them a few moments to think through what you’ve said. A person’s stress rises when they feel rushed. Allowing time brings calm.

Conclusion

Understanding patrons’ well-being and recognizing signs of being outside their window of tolerance is crucial for librarians. The window of tolerance is closely related to promoting empowerment, safety, and trust because it reflects an individual’s capacity to effectively manage stress and regulate emotions. When a person is within their window of tolerance, they feel safe and empowered to engage in activities, communicate openly, and make decisions confidently. This state of balance fosters a sense of trust both within oneself and in relationships with others.

Understanding the window of tolerance also informs librarians’ approach to de-escalation techniques within library settings. By recognizing the signs of hyperarousal or hypoarousal in patrons, librarians can respond with empathy and provide appropriate support to help individuals regulate their emotions and return to their optimal zone. This may include providing a quiet space, sharing stress management resources, and offering empathetic listening. Additionally, suggesting simple activities like sitting in a quiet room or using stress balls can contribute to creating a safe and inclusive space. De-escalation strategies such as active listening, respectful communication, and offering choices align with the goal of facilitating patrons’ return to their window of tolerance. Creating an environment that acknowledges and respects individuals’ emotional boundaries, librarians can cultivate a sense of safety and trust, reducing the likelihood of conflicts and promoting positive interactions among patrons. In this way, the principles of trauma-informed librarianship intersect with de-escalation techniques to create a supportive and inclusive library environment for all.

Reflection questions, for now and later:

- How does understanding the concept of the window of tolerance enhance your approach to interacting with patrons in distress?

- Reflect on a time when you observed someone experiencing hyperarousal or hypoarousal in the library. How did you respond, and what could you do differently next time?

- How might your own emotional regulation impact your ability to effectively de-escalate tense situations in the library?

- Consider the cultural and individual differences that may influence how patrons respond to de-escalation techniques. How can you tailor your approach to be more inclusive and respectful of diverse backgrounds?

- Reflect on the de-escalation techniques discussed. Which ones do you feel most comfortable implementing, and which ones do you find more challenging? How can you further develop your skills in those areas?

- Think about the institutional support and resources available to you when dealing with escalated situations in the library. Are there any additional training or support systems you would like to see implemented?

- How can you foster a culture of empathy and understanding within your library community to prevent conflicts and promote a safe, welcoming environment for all patrons?

- Consider the ethical implications of de-escalation strategies, particularly in situations where patrons may be experiencing trauma or mental health crises. How can you ensure that your interventions prioritize the well-being and dignity of the individuals involved?

- Reflect on the role of communication in de-escalation. How can you improve your active listening skills and nonverbal communication cues to better connect with patrons in distress?

- Finally, consider how you can integrate trauma-informed principles into all aspects of your library practice to create a more supportive and accessible space for everyone.

- Price, Nicole S. n.d. “A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Stanislaus.” ↵

- Ogden, Lydia P., and Rachel D. Williams. 2022. “Supporting Patrons in Crisis through a Social Work-Public Library Collaboration.” Journal of Library Administration 62 (5): 656–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2022.2083442. ↵

- Williams, Rachel, Catherine Dumas, Lydia Ogden, Luke Porwol, Joanna Flanagan, and Julia Tillinghast. 2023. “Empathy, Confidence, and De-Escalation: Evaluating the Effectiveness of VR Training for Crisis Communication Skills Development Among LIS Graduate Students.” Proceedings of the ALISE Annual Conference, September. https://doi.org/10.21900/j.alise.2023.1384. ↵

- Provence, Mary A. 2023. “Three Models of Practice: Impacts on the De-Escalation Role of Library Social Workers During Crises with Patrons Experiencing Homelessness.” Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association 72 (4): 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2023.2262074. ↵

- Löffel, Jerôme S A. n.d. “Measuring the Window of Tolerance in Student’s Daily Life:” ↵

- Hershler, Abby. 2021. “Chapter 4 Window of Tolerance.” In Chapter 4 Window of Tolerance, 25–28. Penn State University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780271092287-008. ↵

- Matickas, M. 2022. “Measuring the Width of the Window of Tolerance and Associations of Interoceptive Sensibility and Arousal in Student’s Daily Life.” Info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis. University of Twente. July 21, 2022. https://essay.utwente.nl/92247/. ↵

- How trauma can affect your window of tolerance | Very Well mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/window-of-tolerance-7553021 ↵

- How trauma can affect your window of tolerance ↵

- Novak, Edward T. 2018. “Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness: Practices for Safe and Transformative Healing.” Transactional Analysis Journal 48 (3): 288–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03621537.2018.1471295. ↵

- “‘What Is Complex Trauma?’ By Michael Guilding Vol 2 Issue1.” n.d. Complex Trauma UK. Accessed May 8, 2024. https://www.complextraumainstitute.org/product-page/what-is-complex-trauma-by-michael-guilding-from-issue-2. ↵

- Corrigan, FM, JJ Fisher, and DJ Nutt. 2011. “Autonomic Dysregulation and the Window of Tolerance Model of the Effects of Complex Emotional Trauma.” Journal of Psychopharmacology 25 (1): 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109354930. ↵

- Gold, Eluned. 2021. “Trauma-Sensitivity.” In Essential Resources for Mindfulness Teachers. Routledge. ↵

- (“‘What Is Complex Trauma?’ By Michael Guilding Vol 2 Issue1,” n.d.) ↵

- https://mi-psych.com.au/understanding-your-window-of-tolerance/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWindow%20of%20Tolerance%E2%80%9D%20is%20a%20term%20used%20to%20describe%20the,in%20what%20we%20are%20doing. ↵

- (“‘What Is Complex Trauma?’ By Michael Guilding Vol 2 Issue1,” n.d.) ↵

- Richmond, Mimi. 2021. “Flexibility and Fusion: A Method to Expand the Window of Tolerance for Clients with Eating Disorders.” Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses, May. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/419. ↵

- Levine, Peter. n.d. “What Resets Our Nervous System After Trauma?” ↵

- Lohrasbe, Rochelle Sharpe, and Pat Ogden. 2017. “Somatic Resources: Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Approach to Stabilising Arousal in Child and Family Treatment.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy 38 (4): 573–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1270. ↵

- Balban, Melis Yilmaz, Eric Neri, Manuela M. Kogon, Lara Weed, Bita Nouriani, Booil Jo, Gary Holl, Jamie M. Zeitzer, David Spiegel, and Andrew D. Huberman. 2023. “Brief Structured Respiration Practices Enhance Mood and Reduce Physiological Arousal.” Cell Reports Medicine 4 (1): 100895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895. ↵

- Carletto, Sara, Martina Borghi, Gabriella Bertino, Francesco Oliva, Marco Cavallo, Arne Hofmann, Alessandro Zennaro, Simona Malucchi, and Luca Ostacoli. 2016. “Treating Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Efficacy of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing and Relaxation Therapy.” Frontiers in Psychology 7 (April): 526. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00526. ↵

- https://paetc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/De-escalation-PACE.pdf ↵

- Price, Owen, and John Baker. 2012. “Key Components of De-Escalation Techniques: A Thematic Synthesis.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 21 (4): 310–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00793.x. ↵

- Bowers, Len. 2013. “A Model of De-Escalation.” Text. Mental Health Practice. August 30, 2013. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp.17.9.36.e924. ↵

- Hallett, Nutmeg, and Geoffrey L. Dickens. 2017. “De-Escalation of Aggressive Behaviour in Healthcare Settings: Concept Analysis.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 75 (October): 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.07.003. ↵

- Richmond, Janet S., Jon S. Berlin, Avrim B. Fishkind, Garland H. Holloman, Scott L. Zeller, Michael P. Wilson, Muhamad Aly Rifai, and Anthony T. Ng. 2012. “Verbal De-Escalation of the Agitated Patient: Consensus Statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA De-Escalation Workgroup.” The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 13 (1): 17–25. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864. ↵

- Spielfogel, Jill E., and J. Curtis McMillen. 2017. “Current Use of De-Escalation Strategies: Similarities and Differences in de-Escalation across Professions.” Social Work in Mental Health 15 (3): 232–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2016.1212774. ↵

- https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/workplace-violence/CPI-s-Top-10-De-Escalation-Tips_revised-01-18-17.pdf ↵