9. A Practical Guideline on How to Tackle Interdisciplinarity

A practical guideline on how to tackle interdisciplinarity—A synthesis from a post-graduate group project

Abstract

The comprehensive understanding of increasingly complex global challenges, such as climate change induced sea level rise demands for interdisciplinary research groups. As a result, there is an increasing interest of funding bodies to support interdisciplinary research initiatives. Attempts for interdisciplinary research in such programs often end in research between closely linked disciplines. This is often due to a lack of understanding about how to work interdisciplinarily as a group. Useful practical guidelines have been provided to overcome existing barriers during interdisciplinary integration. Working as an interdisciplinary research group becomes particularly challenging at the doctoral student level. This study reports findings of an interdisciplinary group project in which a group of doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers from various disciplines faced the challenges of reconciling natural, social, and legal aspects of a fictional coastal environmental problem. The research group went through three phases of interdisciplinary integration: (1) comparing disciplines, (2) understanding disciplines, and (3) thinking between disciplines. These phases finally resulted in the development of a practical guideline, including five concepts of interactive integration. A reflective analysis with observations made in existing literature about interdisciplinary integration further supported the feasibility of the practical guideline. It is intended that this practical guideline may help others to leave out pitfalls and to gain a more successful application of interdisciplinarity in their training.

Introduction

The large economic, ecological, and demographical challenges caused by globalization led to the transition towards interdisciplinary collaborations between scientific communities, policymakers, and society (Langfeldt et al., 2012; Pedersen, 2016). Integration of diverse understandings by interdisciplinary collaboration is seen as most comprehensive approach to complex environmental problems (Bromham et al., 2016; Ledford, 2015a; Wagner et al., 2011). For example, a paragon for addressing a complex environmental problem was reported for Nova Scotia, Eastern Canada. In this study a group of decision makers from industry, policy, research, communities, as well as, fishery assessed an interdisciplinary way to sustainably harness tidal energy potential (Palmer, 2018). In academia, however, discoveries are said to be more likely on the boundaries between disciplines. In this case the latest methods and perspectives can increase knowledge during interdisciplinary research collaborations (Rylance, 2015). In contrast, single-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary research collaborations increase impact output in highly specialized fields. Therefore, interdisciplinary research collaboration fosters deeper interaction and integration of various disciplinary perspectives (Bergen et al., 2020; Gewin, 2014; Pykett et al., 2020; Sá, 2008; Van Noorden, 2015).

In order to successfully investigate intricate problems, all involved parties have to communicate and collaborate in an attempt to create a common understanding and to learn from each other’s perspectives. This ideally results in a new perspective that is more than the sum of its components (Brewer, 1999; Nissani, 1997; Tauginienė et al., 2020). As a result, global governance recognizes interdisciplinary research as the best way to address emerging multifaceted problems. Therefore, interdisciplinary programs were strongly encouraged over the last decades (Bozeman and Boardman, 2014; Ledford, 2015b; Pedersen, 2016; Rylance, 2015), including interdisciplinary research graduate programs. Among others, the US graduate program Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship1 (IGERT) and the Toolbox Dialogue Initiative2 appear to be good showcases for interdisciplinary approaches (Eigenbrode et al., 2007; Goring et al., 2014; Kennedy et al., 2012; Laursen, 2018; Pennington et al., 2013; Steel et al., 2017). Another typical example for an interdisciplinary research training program is the Trust and Communication in a Digitized World program, which examines how trust can be developed and maintained under the conditions of new forms of communication.3

To date, a broad range of interdisciplinary graduate education programs have been established to address cross-cutting environmental and sustainability problems (Bruce et al., 2004; Campbell, 2005; Graybill et al., 2006; Juhl et al., 1997; McCarthy, 2004; Morse et al., 2007; Morss et al., 2005; Rhoten and Parker, 2004; Skates, 2003). Nonetheless, from the doctoral student’s perspective the focus on interdisciplinary research may not be trivial, because in order to conclude their work in a time frame that is often narrowly predetermined, doctoral students rarely have the opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of disciplines outside of their own field (Welch-Devine, 2012; Welch-Devine and Campbell, 2010). Collaboration efforts mostly come in the form of the exchange of expertise between closely related disciplines, for example in collaborations between geology and biology. In such disciplinary and cross-disciplinary investigations the integration of disciplines is straightforward. However, interdisciplinary collaboration efforts between disciplines not as obviously related to each other, for example social and natural sciences, can introduce misunderstandings because of stereotypes (MacLeod, 2018). This can hinder research progress, leads to unnecessary repetition or, in the worst case, can have negative consequences when misunderstood theories are applied in improper contexts (Campbell, 2005). In post-graduate training programs, these problems are further complicated as doctoral students are still at the stage of mastering the vocabulary of their own disciplines, while, because of the large time effort, being less interested in working out the meaning from another discipline’s perspective.

Practical guidelines from established literature are commonly the first choice to tackle interdisciplinary integration and research process (Brandt et al., 2013; Brown et al., 2015; Lang et al., 2012). It is also beneficial to reflect on assumptions originating from the different disciplinary perspectives. An efficient communication framework favours respectful attitudes within the research group, resulting in effective cooperation rather than competition. Repko and Szostak (2020) and Menken and Keestra (2016) synthesized case studies about interdisciplinarity and provided a good roadmap and interdisciplinary research model how to work interdisciplinarily.

One of the most prominent examples for interdisciplinarity is the effect of climate change on the coastal environment. It comprises of an interacting web of various disciplines covering, for example, atmospheric and oceanographic issues, biological consequences, economic interests, societal concerns, legal commitments, political action as well as ethical implications. Our study aims to extent the existing scientific literature about interdisciplinary integration by focusing on the perspective of post-graduates working in the coastal environment. We reflect on an interdisciplinary group project in which doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers from the interdisciplinary training program INTERCOAST, having different single disciplinary backgrounds, faced challenges of interdisciplinarity in a fictional coastal environmental problem. From our observations about advantages and challenges of interdisciplinarity, a practical guideline was synthesized that could help to educate post-graduates with different backgrounds to face an interdisciplinary problem as a group and how to bypass the pitfalls when it comes to interdisciplinary group work.

Methods

Background and composition of the group project

The post-graduate training group Integrated Coastal Zone and Shelf-Sea Research (INTERCOAST) was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft from 2009 to 2018 and was a collaboration between the University of Bremen (Germany) and the University of Waikato (New Zealand). The premier goal of INTERCOAST was to gain an integrated understanding of the coastal environment from oceanographic, sedimentological, biological, socio-economic, and legal perspectives. INTERCOAST consisted of 47 individual research projects, which until now resulted in ca. 100 publications in peer-reviewed journals and books. At present, the majority of these publications aimed on disciplinary research questions, whereas only few interdisciplinary studies have been published (Koschinsky et al., 2018; Markus et al., 2015). Apart from the high level of disciplinary research, the focus of INTERCOAST was also set on interdisciplinary education, which was provided to the post-graduates through workshops and group projects.

From October 2014 to September 2015, 12 doctoral students and two postdoctoral researchers set up an interdisciplinary group project in which a problem related to the coastal environment was investigated to gain a better understanding from different disciplines. The proponents involved in the group project came from different academic disciplines and therefore had considerably different professional expertise about the coastal environment. Research topics that were covered by the proponents of the group project included, but were not limited to, studying iron enrichment in coastal sand deposits (Kulgemeyer et al., 2017), various coastal erosion processes (Bartzke et al., 2018; Biondo and Bartholomae, 2017; Blossier et al., 2017; Kluger et al., 2017, 2019; Staudt et al., 2017), expansion mechanisms of invasive seaweeds (Bollen et al., 2017), the public discourse of coastal protection in Germany (Scheve, 2017), and legislative differences between Germany and New Zealand regarding underwater cultural heritage. The proponents of the group consisted of geoscientists, biologists, social scientists, and legal scientists, with geoscientists representing the majority (Table 1). The bias in group composition arose from the large quantity of individual research projects that focused on geoscientific topics. The number of group proponents was restricted to 14 as this was the number of doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers who were available during the time period of the group project.

Setup of the group project

Literature reports that three main goals of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research efforts need to be established within their own programmatic routines (Brandt et al., 2013; Lang et al., 2012). First, a research group forms around a commonly agreed integrated research question. To this end, it is important to identify an aim that does not privilege any involved discipline over another (Campbell, 2005). Further, it is necessary to create a common understanding of the different disciplinary concepts, vocabulary, methods, and values. Finally, an interactive communication framework needs to be set up to allow for an efficient sharing of the on-going research within the group. The group project reported in this study lasted for 11 months and was divided into three phases (Table 2), which were loosely associated with the three goals of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research described above: (1) phrasing an integrated research question, (2) creating a common understanding, and (3) establishing an interactive communication framework.

During the first 9 months (Phase 1), the postdoctoral researchers organized monthly group meetings. These group meetings consisted of an informal joint lunch break and a subsequent formal seminar. The formal seminar commonly lasted for 2 h and was organized and moderated by the postdoctoral researchers. In the first formal seminar, the group brainstormed about interdisciplinary topics related to the coastal environment in an open discussion. The decision about whether a topic was considered interesting and relevant to the coastal environment was made based on a rather superficial discussion among the group, without taking external expertise or research into account. The selection of relevant topics was not based on democratic decision, for example by means of a vote. A topic was considered interesting and relevant to the coastal environment when at least one proponent of the group supported the suggested topic and nobody expressed an objection. From these topics, the group chose the most interesting and relevant topic and framed a common research problem for further literature research. Wind energy production was selected as common research problem due to its broad applicability to the different disciplines and its prominence in the context of current societal and technical developments related to climate change. The agreement about a common research problem was achieved by an open vote.

The next step consisted of literature research: Each post-graduate had the task to familiarize themselves with one aspect of the common research problem, e.g. noise emission of wind turbines, while focusing on differences between the four disciplines, and prepared a short 10-min presentation about the selected aspect of the common research problem. The group did not monitor how long each individual post-graduate worked on the literature research and the preparation of the presentation. During seminars 2–6, the post-graduates presented their selected aspect of the common research problem to the entire group. Each presentation was followed by a 30-min to 1-h discussion phase during which the proponents of the group discussed the presented aspect in the light of their personal knowledge.

During seminars 7–9, the group phrased a commonly agreed research question. This process started with a discussion about the expected final outcome of the group project. At the end of the seventh seminar, the group agreed on (1) framing one integrated research question related to the common research problem and (2) answering this question interdisciplinarily. The eighth seminar was spent on framing the integrated research question. Several research questions were suggested by proponents of the group. Out of the several research questions, the group established a commonly agreed interdisciplinary research question by means of an open vote, namely:

“How do natural, social, and legal disciplines change in importance and interconnectivity when comparing potential wind farm locations (a) offshore within exclusive economic zone, (b) offshore within territorial sea, and (c) onshore near the coast?”

The ninth seminar was spent by the group to discuss and agree on the strategy to answer the integrated research question. The group decided to answer the integrated research question through phases 2 and 3 as explained below. The group did not monitor the involvement of individual group proponents during the process of phrasing the integrated research question. The authors therefore cannot judge about whether the idea of studying an interdisciplinary problem with a common research question was triggered by a single proponent of the group, or rather developed successively from the entire group’s discussion.

During the 10th month (Phase 2), the proponents of the group were asked to split into four multidisciplinary subgroups and prepared 30-min group presentations, which were supposed to address the research question by focusing on one of the four disciplines (Table 1). Each subgroup consisted of one expert from her/his own discipline by training. The other proponents of the subgroups had professional expertise in one of the four disciplines. For example, a social scientist, two geoscientists, and one biologist formed a subgroup with focus on societal aspects in respect to the research question. The social scientist was the expert of this subgroup, moderated the progress within the subgroup, and could help the other proponents of the subgroup in case of misunderstandings related to social scientific issues. The subgroups formed randomly; because of the relatively small number of proponents participating in the group project, they were not always composed of researchers from all four disciplines. The content of the group presentation was divided equally among the proponents of the subgroup to provide the possibility that every proponent would contribute equally to the outcome of their group presentation. The group did not monitor how long each subgroup prepared themselves for their group presentation. The authors acknowledge that an equal contribution is difficult to judge upon due to different personalities of the group proponents. One proponent might spend more effort and time to her/his part of the group presentation than others, or vice versa. The subgroups presented their findings to the entire group during the first day of a 2-day off-campus retreat. Each of the four presentations were followed by a discussion phase. During the discussion phase, the proponents of the group were asked to focus on how the four disciplines addressed the research question in their group presentation. This approach was chosen to create a common understanding of the different disciplinary concepts, vocabulary, methods, and values relevant to the research question. The final outcome of the discussion phase was the common agreement throughout the group to perform a role play as interdisciplinary interactivity.

Phase 3 started with the role play, which was conducted on the second day of the 2-day off-campus retreat. The aim of the role play was to transfer the integrated knowledge gained from the group presentations into an interactive communication framework. The role play included a 2-h planning phase, followed by a 2-h preparation phase, the actual role play (ca. 1 h), and was completed with a 2-h discussion phase. In the planning phase, the proponents of the group nominated different communication scenarios in which the research question could be addressed by all four disciplines. The group decided that the role play would be framed in an open forum in which actors, representing the four disciplines’ interests, would discuss where to construct a future fictional wind farm in Germany. Afterwards, all group proponents slipped into a role and prepared themselves for their part in the role play. One group proponent proposed the role of a moderator. The proponents chose roles based on their individual interests and preferences in order to increase motivation and to maintain a long and interesting discussion among proponents of the group.

The role play took place in a seminar room and the actors were seated in a circle of chairs. The moderator started the role play by introducing him/herself and the reasoning for an open forum. Subsequently, the other actors introduced their role and made a first statement in which they highlighted their role and their role’s opinion, as in the case of the present study, in the process of wind farm construction. Afterwards, a discussion started among the actors. This discussion was only loosely framed by the moderator, giving the actors space to freely interact and communicate within the group and respond to other actors’ opinions. The moderator ensured that all actors had the chance to contribute equally to the role play. Although it has to be acknowledged that the actors contributed differently due to their different personalities and role. After the role play, the proponents of the group discussed the outcome of the role play with respect to importance of the different actors and their interconnectivity between actors.

During two 6-h seminars, which took place in the month after the 2-day off-campus retreat, the group went through a phase of intense reflection in order to answer the research question stated above. The first seminar was spent on finding a way to visualize the involvement and role of each discipline in regard to the three locations for wind farm construction. The group decided to develop a conceptual model. In the second seminar, the group created the conceptual model. All group proponents took part in the seminars, but the group did not monitor whether or not all proponents contributed equally to the final conceptual model.

Results

Phrasing an integrated research question—Phase 1

The integrated research question was phrased during group meetings, which took place in monthly intervals during the first 9 months of the project (Table 2). Informal joint lunch breaks formed the first platform of the group meetings. It was observed that doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers exchanged private and professional topics during the lunch breaks without paying much attention to the disciplinary perspectives. Proponents had the time and space to explain misunderstandings that arose from the conversations throughout the group. It was observed that the group dynamics changed over time. During the first lunch breaks, proponents were mostly interested in private topics or in professional topics related to their own disciplines. At the end of the 9 months period of phase 1, it was observed that the proportion of professional topics that were not related to their own disciplines increased. This shows that the informal lunch breaks nurtured interdisciplinary emphasis of the group.

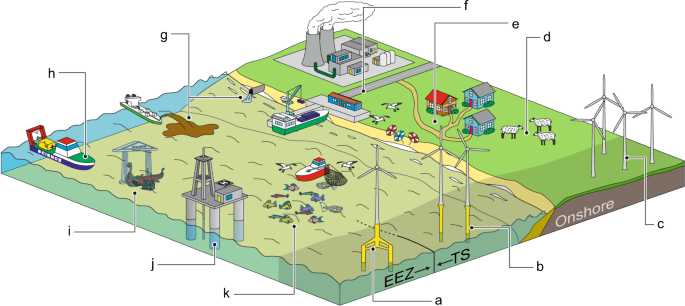

Formal seminars formed the second platform of the group meetings. During the first formal seminar, the proponents brainstormed about topics relevant to the coastal environment and created a mind map. For the present study, this mind map was visualized as perspective map in Fig. 1. Relevant topics to the coastal environment considered by the group included, but were not limited to, wind energy production, food production, tourism and residential areas, industry and infrastructure, waste water disposal and dredging, marine resources, and underwater cultural heritage. The proponents divided the coastal environment into three areas of interest, namely (1) onshore near the coast, (2) offshore within territorial sea (up to 12 nautical miles offshore), and (3) offshore within exclusive economic zone (up to 200 nautical miles offshore). After an intense discussion and numerous refinements, the research group decided that the challenge of increasing the proportion of wind energy production within the next decades would probably be the most relevant topic for interdisciplinary research in the three areas of interest today (Deutscher Bundestag, 2014; Ender, 2017). Therefore, the commonly agreed research problem was framed on understanding the complex roles and interactions between disciplines when searching for an appropriate coastal wind farm location. During phase 1 it was observed that for the proponents it was of particular importance to be able to identify themselves with the chosen research problem with respect to their disciplinary background and to share their expertise with the group.

The dark-shaded area highlights the three different locations for wind farms, which are the commonly agreed research areas of the interdisciplinary group work. The three areas include a–c offshore within exclusive economic zone (EEZ), offshore within territorial sea (TS), and onshore near the coast. Alternative suggestions for research areas include d farming, e tourism and residential areas, f industry and infrastructure, g waste water disposal, dredging, and dumping, h scientific surveys, i underwater cultural heritage, j marine resources, and k fishery.

The post-graduates presented their literature research about one aspect of the common research problem (seminars 2–6). At this stage, the definition of a specific research question was not the premier goal of the group. The group was more concerned with the establishment of a common understanding of interdisciplinary aspects within the research problem. It was observed that the aspects chosen by the proponents still remained in their own disciplines during this phase. For example, biologists chose to read literature about bird collision within offshore wind farms or whether or not noise emission would affect the behaviour of marine mammals. A geoscientist was more concerned about the possible difficulties of predicting the sediment stability around wind turbines located in a highly dynamic environment. A social scientist read literature about public perception of onshore and offshore wind farms, whereas a legal scientist studied the differences of regulatory frameworks of wind farm constructions between the different areas of interest. In the following seminars, the proponents seemed to become more familiar with the other disciplines in the group and, but more importantly, appeared to develop an interest to understand the other disciplines’ arguments and concerns. We believe that this transformation towards interdisciplinary group work was mainly initialized by the exchange of personal and professional opinions during the informal lunch breaks.

The phrasing of a commonly agreed research question (seminars 7–9) turned out to be a long-lasting process. Proponents discussed about topics such as the usefulness of phrasing a single integrated research question or the general thematic focus of the question. The hierarchy of words were a matter of discussion too. Proponents argued about, for example, whether or not the order of disciplines as phrased in the research question (“How do natural, social, and legal disciplines […]”) would refer to some kind of a hierarchical order. It was observed that proponents with social and legal professional backgrounds were more actively focusing on levelling the hierarchy of disciplines than the natural scientists. This was probably because social and legal disciplines formed the minority within the group, felt underrepresented, and attempted to strengthen their position.

During the process of phrasing a common research question, the group decided to name the group project InterWind, being a word combination of interdisciplinarity and wind farms. The title of the group project was initially suggested by one of the doctoral students and was later commonly accepted by the entire group. The authors believe that establishing both a common research question and a project name was the most important step for the proponents to identify themselves with the research project. This was especially important because the doctoral students performed the group project also during the last year of their Ph.D. and were therefore preoccupied with other topics.

Creating a common understanding—Phase 2

Multidisciplinary group work was used as a tool to improve the understanding of the different disciplines with respect to the common research question and to encourage interdisciplinary thinking. The proponents of the subgroup approached interdisciplinary thinking from different perspectives. On the one hand, the expert functioned as mentor and could observe and comprehend the other proponents’ struggles and difficulties when facing an unrelated discipline. On the other hand, the proponents of unrelated disciplines enjoyed the immediate benefit from explanations and advices provided by the expert in cases of misunderstandings. The exchange of these two different perspectives within subgroup encouraged interdisciplinary thinking.

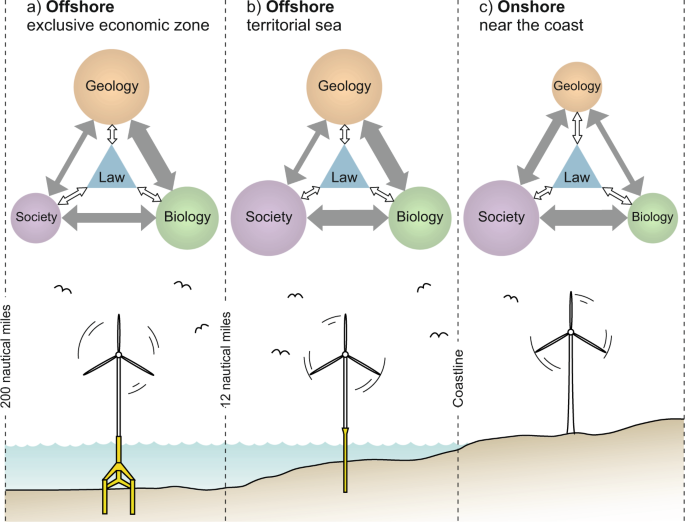

The multidisciplinary subgroups presented their findings to the entire group during the first day of the off-campus retreat. In the presentations, the subgroups focused not only on their acquired knowledge but also on their impressions and personal experiences during the multidisciplinary group work. For example, one of the multidisciplinary group presentations focused on how the procedure of wind turbine construction differs throughout the three areas of interest. Among other aspects, it was presented that the type of foundation may differ from a surface foundation in the onshore environment to monopile and tripod foundations in the offshore environment. For the present study, this example was visualized in the lower panel of Fig. 2. The differences between these three types of foundations were presented from legal, geoscientific, and biological perspectives. The subgroup did not find any societal topics related to the type of foundations. Another subgroup presented the impact of wind turbines on bird migration. The proponents showed that in the public perception, collision with wind turbines as a consequence of bird migration is considered a major obstacle for the construction of wind turbines (Devlin, 2005). However, recent systematic studies showed that birds tend to avoid the wind turbines and that the thread for collision is highly overestimated in the public (Hüppop et al., 2006).

It represents the different weighting (circle size) and interactivity (arrow width) of the four disciplines in the context of wind farm construction between a offshore within the executive economic zone, b offshore within the territorial sea, and c onshore near the coast.

These discrepancies between disciplines observed in the group presentations were vividly discussed by the group. The group decided to class the discrepancies with respect to the three areas of interest (onshore near the coast, offshore within territorial sea, and offshore within exclusive economic zone). In the following, the authors describe the main findings the group made about the differences between disciplines with respect to the three areas of interest.

In the onshore environment near the coast, the group considered geological and biological environmental constraints lower in importance compared with the offshore areas. The main reason for this consideration was that, because onshore wind turbines are commonly built in anthropogenically modified areas, they commonly require simpler ground investigations and have a limited effect on the ecosystem. In contrast, the group considered the impact on society, represented by for example land owners and tourists, as comparatively large (Wolsink, 2007). The group explained this conclusion with the high visibility of onshore wind turbines. In areas where the available space is already limited, people may object the construction of wind turbines despite the numerous positive effects on environment and economy.

In the offshore environment, the group discussed that various geological aspects, such as the presence of strong wind and hydrodynamic loads, the sediment properties of the subsoil, and the wind turbine design, have to be accounted for (BSH, 2014). Biological aspects include the possible effects of wind turbines on the marine ecosystem (Desholm and Kahlert, 2005; Elmer et al., 2007) as well as long-term climate variability due to reduction in carbon dioxide emission (Kempton et al., 2007). The group considered societal aspects high within the territorial sea as the tourism industry and public acceptance may be influenced in cases where offshore wind farms are visible from the coast (Devine-Wright and Howes, 2010; Gee, 2010). In the exclusive economic zone, societal impacts are mainly limited to shipping industry and fishery (Berkenhagen et al., 2010). Due to the large distance from the coast, offshore wind farms are generally more accepted by coastal communities and negative effects on coastal tourism are low (Hübner and Pohl, 2016; Hübner and Pohl, 2014). Therefore, the group considered societal aspects smaller in the exclusive economic zone compared with the territorial sea. The legal aspects, such as the regulatory framework for wind farm construction in Germany (BSH, 2014) was considered as equally important throughout the three areas of interest.

The group further focused on comparing the interactions between disciplines within the three areas of interest. The group considered that the society emphasizes with fauna and flora more easily than it does with practical aspects of geology, such as geotechnical engineering efforts when searching for a wind farm location. Therefore, the group weighted interactions between society and biology higher than those between society and geology. The highest interactions were considered to exist between society and biology when wind farms form part of the landscape (onshore and offshore within territorial waters) (Gee, 2010).

Establishing an interactive communicative framework—Phase 3

In the third phase, the group performed a role play in order to transfer the integrated knowledge gained from the group presentations into an interactive communication framework (second day of the off-campus retreat). The role play was framed in an open forum in which stakeholders from one of the four disciplines discussed where to construct a future fictional wind farm. The roles’ opinions reflected various aspects of the decision process of wind farm constructions and encompassed, among others, a local resident, a wind farm operator, an eco-activist, a federal politician, and an employee working for a federal maritime agency. During the role play the proponents had to emphasize with their new role and built a line of argumentation based on their role’s best interest. As the communication proceeded, the actors emphasized with the perspectives of the other roles, made compromises, and finally decided on a wind farm location every actor could agree upon.

The group went through intense discussions and reflections about the group presentations and the role play in order to find and agree on an integrated answer to the common research question. The group agreed that the complex roles of disciplines and interactions between disciplines with respect to the three areas of interest could be best synthesized by means of a conceptual model (Fig. 2). The group decided that the conceptual model should be divided into the three areas of interest. Each subdivision should consist of four geometrical shapes each of them representing one of the four disciplines. The size of geometrical shapes should reflect the group’s decision about the dominance of individual disciplines over other disciplines in the area of interest, respectively. Arrows of different widths would connect the four geometrical shapes in order to visualize a degree of interaction.

The group agreed that the legal framework provides the basis of interactions between the other three disciplines. Therefore, the law discipline was put into the centre (or heart) of the conceptual model. A triangular shape was chosen for the law discipline, symbolizing a cogwheel that drives the interactions and communications between the other disciplines. The other three disciplines were symbolized as circular shapes that surround the law triangle. The circular shape was chosen to be different from the law triangle, but without taking any other meaning into account. Note that the relative position and colour of circles do not indicate any hierarchical order of the disciplines but were chosen solely for a better illustration of the conceptual model.

The relative weighting of the disciplines and their degree of interaction were subject to long discussions throughout the research group. The final conceptual model (Fig. 2) was the result of various refinements that were made by all group proponents of all four disciplines and may therefore be considered as a truly interdisciplinary outcome. The conceptual model could indicate weaknesses in current practices and involvements of disciplines regarding wind farm constructions.

Discussion

Practical guideline for interdisciplinary research process

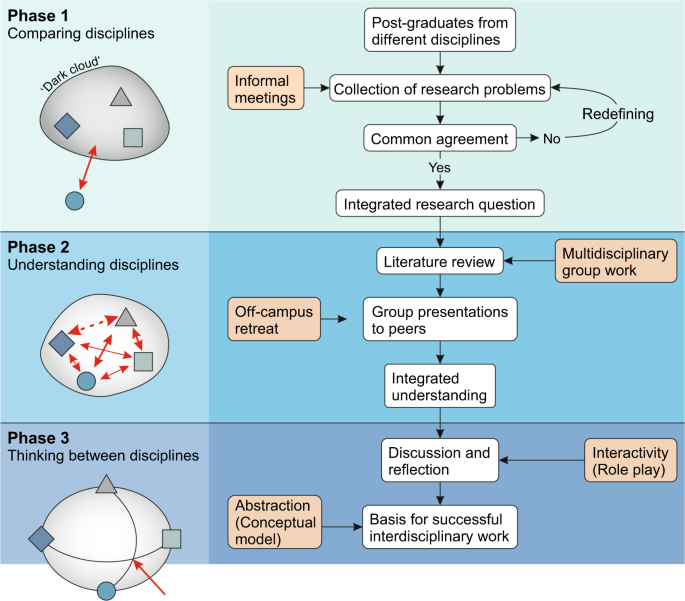

All observations made during the interdisciplinary group project were synthesized into a practical guideline (Fig. 3) that may help other research groups composed of various disciplines to engage in an interdisciplinary problem. The practical guideline is conceptualized as a sequence of three phases of interdisciplinary integration: (1) comparing disciplines, (2) understanding disciplines, and (3) thinking between disciplines. The basic concept of these three phases follows the suggestions made by Lang et al. (2012) for transdisciplinary research process, who divided integrative research process into (1) problem framing and team building based on a societal and/or scientific problem, (2) co-creation of solution-oriented transferable knowledge, and (3) (re-)integration and application of created knowledge in both societal and scientific practice. The conceptual model of Lang et al. (2012) has many similarities to other models in the literature (Carew and Wickson, 2010; Jahn, 2008; Krütli et al., 2010; Talwar et al., 2011) and was adopted by numerous researchers (Brandt et al., 2013; Mauser et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2014).

Geometric objects (triangle, square, circle, and diamond) indicate different disciplines. The term ‘dark cloud’ refers to an unresolved challenge that has to be encountered interdisciplinarily.

The conceptual model synthesized in the present study (Fig. 3) starts with phase 1: Comparing disciplines. Doctoral students and/or postdoctoral researchers, originally having professional backgrounds in a single discipline, form a group and collect ideas about a common research problem through group meetings. A commonly agreed research problem is framed through iterative refinements throughout the group proponents, before the group decides upon an integrated research question. In phase 1, proponents may face problems and misunderstandings when trying to emphasize with the other disciplines. The limited understanding about the other disciplines is illustrated in the conceptual model by a dark cloud, which every proponent of the group must enter in order to find an integrated research question (as symbolized in the left part of Fig. 3). Group meetings that combine informal lunch breaks with subsequent formal seminars were found to be a successful tool for helping proponents to compare disciplines, to collect ideas for a research problem, which does not privilege one discipline over another, and to finally reach a common agreement on an integrated research question.

Lang et al. (2012) emphasized that the individual phases of transdisciplinary research process are not likely to be a linear process but often have to be performed in an iterative manner in order to reflect about transdisciplinarity. Based on the methodological approach of the present study, the three phases of the practical guideline followed a predefined chronological sequence, without allowing any iterative adjustments between phases. However, within phase 1 an iteration step was included that allowed a refinement of the common research problem.

In phase 2, the group establishes a common understanding of the different disciplines through multidisciplinary group work. The different perspectives of expert and non-experts during multidisciplinary group work nurtures empathy of proponents when dealing with unknown disciplines. The proponents familiarize themselves with an unknown discipline during their own literature review, can discuss and change perspectives during the preparation of multidisciplinary group presentations, and can finally benefit from listening to and discussing about other presentations being held in an atmosphere not related to normal work environment, for example during an off-campus retreat. During this process, each proponent enters the dark cloud of disciplines, previously considered to contain research fields largely unrelated to each other, to steadily form an interconnected transdisciplinary framework (as symbolized on the left side of Fig. 3).

In phase 3, the group discusses and reflects about the findings with respect to the integrated research question through an interactivity, for example a role play. The answer to the integrated research question should reflect the ability of the group for successful interdisciplinary work. An abstraction, for example using a conceptual model, could be a helpful way to reduce complexity and ensure an answer that can be accepted by the entire group. During this process, the proponents finally start to understand the integrated problem as multidimensional complex of disciplinary interrelations and learn to think at the interfaces between disciplines (as symbolized on the left side of Fig. 3).

Our practical guideline for approaching an interdisciplinary problem may be considered as an extension to the conceptual model for transdisciplinary research process of Lang et al. (2012). It largely follows the three proposed phases of research process but also incorporates five new concepts, namely group meetings, multidisciplinary group work, an off-campus retreat, an interactivity, and an abstraction of interdisciplinarity that enable the research group to approach an integrated problem interdisciplinarily.

Our practical guideline is endorsed by the five principles of interdisciplinary collaboration presented by Brown et al. (2015). Here the researchers initially undergone through a phase of “forging a shared mission”, which provided an overall goal of collaboration. The shared mission needed to be formulated broad enough to incorporate meaningful roles for all disciplinary researchers involved. This principle was also observed by us during the process of phrasing an integrated research question in phase 1 as shown in our practical guideline. Brown et al. (2015) further described the usefulness of “T-shaped researchers” (Hansen and Von Oetinger, 2001). Such researchers are reported as experts in their own discipline, but are also capable of looking beyond their scope. In our practical guideline, the development of T-shaped researchers was nurtured through the multidisciplinary group work in phase 2 and the interactivity in phase 3. By this, the students have transferred into T-shaped researchers. In particular, by learning that an active engagement with other disciplines is important, and hence, understanding and appreciating their norms, theories, approaches, evolved as an important step towards interdisciplinary collaboration.

We believe that our practical guideline will help others facing similar challenges of interdisciplinarity and we are looking forward to future initiatives that incorporate the practical guideline into their interdisciplinary education. Nonetheless, we think that our presented guideline describes a practical approach to transform a disciplinary thinking group to an interdisciplinary working team efficiently.

Advantages and challenges of interdisciplinary group work

The interdisciplinary group project revealed a number of issues that are common among other interdisplinary and transdisciplinary working groups. The group project was biased in terms of disciplinary diversity. The majority of proponents had a background in natural sciences, while only few proponents came from social and legal science disciplines. The bias between disciplines arose from the relatively small number of participants, which possibly affected the weighting of one discipline over another during the three phases of interdisciplinary integration, especially during the multidisciplinary group work. Asymmetry in interdisciplinary integration was also mentioned by Viseu (2015). She pointed out that social sciences are often brought into a research team after the project already have been started. Moreover, social scientists sadly form the minority, lack in independence and funding, which eventually leads to a hampering in knowledge production. For future interdisciplinary group projects, we recommend that all disciplines are equally involved during all phases of interdisciplinary collaboration. This will avoid problems related to an unequal distribution and weighing of disciplines within the research group.

Communication problems on topics of mutual interest is famously and anecdotally a common problem in interdisciplinary collaboration. While the general challenges as well as the benefits have long been recognized (Brewer, 1999; Nissani, 1997), we would like to discuss some of the struggles that came with this project with concrete examples. The problems we encountered fall broadly into three categories: language (definition of terms, implicit assumptions), form (writing style, structure, organization), and prejudice (overcoming of stereotypes).

Language-based problems primarily appeared where certain words have different definitions in colloquial language and the technical terminology of one of the scientific disciplines. While this was rarely the cause for complete misunderstandings, it often led to lengthy discussions about the phrasing in written form. An example is the word coast: In casual conversation, it is more or less synonymous with beach or shore and can be understood as where the land meets the sea; this would also be the definition most people would use in an interview for a sociological study. Geological definitions of the coastal system include significant portions of the continental shelf up to the shelf break, as well as inland areas that are still affected by coastal processes, for instance by dune formation. For legal purposes, distinctions are made between land, territorial waters, exclusive economic zone, and international waters. These kinds of discussions are an important part of the interdisciplinary process and a sufficient amount of time should be set aside for them.

Formal problems arose when decisions had to be made about content and order of information, both in the oral presentations and during the preparation of the present paper. Natural sciences make extensive use of graphical forms of presentation in the form of diagrams and sketches—a rarity at best in legal sciences, which in turn make good use of footnotes for clarification and additional information. Differing viewpoints exist about the need to quantify data or the appropriateness of qualitative descriptions. The order in which information is presented greatly influences the focus set for the audience. The audience itself is also a decisive factor; especially a mixed audience of experts from different fields has very heterogeneous expectations that can hardly be satisfied all at once. For the present paper, decisions were made regarding style, structure, significance of findings, and even writing conventions like first vs. third person and formal tone.

Prejudice might come as an unexpected challenge. Post-graduates of their various disciplines have been trained in the environment of a certain academic culture that they tend to identify with. This includes to distinguish their own discipline from others, often in the form of humorous observations about their aims, practices and usage as well as the perceived ranking of the respective disciplines on a scale of scientific value (with their own discipline of course close to the top).

Later in their career, when post-graduates become experts, they find themselves in a position where they need to justify their research in competitive environments, including the frequent search for future funding or constant rate of publications in a high-impact journal. By necessity, they learn to present their work in a way that highlights its values. Although few scientists will consciously think lesser of their colleagues, some may fall into the trap of unconsciously evaluate other disciplines less favourably than their own. From the observations made in the present study, the reason for bringing disciplines together is not to make scholars experts on all things (a rather hopeful goal) but to enable them to collaborate on a shared and integrated question. Apart from knowledge exchange itself and learning from each other, it is important that they trust each other’s expertise. Perhaps the most important thing to highlight is that post-graduates need to learn how to engage with other disciplines. This line of thinking is further supported by unfamiliarity with the tools and premises of said disciplines and is especially present in interdisciplinary environments where hard and soft sciences are part of the same group project. In this way, interdisciplinary projects can provide unique benefits, both to the work itself by enabling a greater inclusiveness and the ability to recognize more facets of a problem, as well as to the persons involved by broadening their horizon and facilitating scientific exchange.

One success of group projects, such as the one of the present study, is that it provided time and space for such conversations and argumentations. Without working through a structured process on this case study, the opportunity would have never arisen to learn about important differences between disciplinary structures and methods. Nor would most proponents of the group have a chance to examine their own assumptions about scientific vocabulary and consider alternate meanings of basic terms. These encounters and moments were only made possible through the group project, which proved its value in training early career scientists to work cooperatively across disciplinary boundaries. Overcoming these problems requires the willingness to compromise. The potential downside can be a loss of precision in some aspects of the work, which has to be pointed out and balanced by references to specialized literature.

Conclusion

The present study reports findings about an interdisciplinary group project in which doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers with natural, social, and legal professional backgrounds faced challenges of interdisciplinarity. Results of the group project include in a practical guideline, which extends existing conceptual models about transdisciplinary research process by introducing a concept that helps research groups to approach an integrated problem interdisciplinarily. In synthesis, the group went through three phases of interdisciplinary integration, namely (1) comparing disciplines, (2) understanding disciplines, and (3) thinking between disciplines.

- A group of doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers collect ideas about a common research problem through group meetings and frame an integrated research question by iterative refinements. Group meetings combine informal lunch breaks with subsequent formal seminars and were found to be an effective too for helping proponents to initiate interdisciplinary thinking.

- A common understanding about the different disciplines’ perspectives is established through multidisciplinary group work of experts and non-experts. The different perspectives of expert and non-experts during multidisciplinary group work nurtures empathy of proponents when dealing with unknown disciplines. Group presentations and subsequent discussions in an atmosphere not related to normal work environment help to steadily form an interconnected transdisciplinary framework between disciplines.

- The group discusses and reflects about the findings with respect to the integrated research question through an interactivity, for example a role play. The answer to the integrated research question should reflect the ability of the group for successful interdisciplinary work. An abstraction, for example using a conceptual model, could be a helpful way to reduce complexity and ensure an answer that can be excepted by the entire group.

References

-

Bartzke G, Schmeeckle MW, Huhn K (2018) Understanding heavy mineral enrichment using a three-dimensional numerical model. Sedimentology 65(2):561–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12392

-

Bergen N, Hudani A, Khan S, Montgomery ND, O’Sullivan T (2020) Practical considerations for establishing writing groups in interdisciplinary programs. Palgrave Commun 6(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0395-6

-

Berkenhagen J, Doring R, Fock HO, Kloppmann MHF, Pedersen SA, Schulze T (2010) Decision bias in marine spatial planning of offshore wind farms: problems of singular versus cumulative assessments of economic impacts on fisheries. Mar Policy 34(3):733–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2009.12.004

-

Biondo M, Bartholomae A (2017) A multivariate analytical method to characterize sediment attributes from high-frequency acoustic backscatter and ground-truthing data (Jade Bay, German North Sea coast). Cont Shelf Res 138:65–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2016.12.011

-

Blossier B, Bryan KR, Daly CJ, Winter C (2017) Shore and bar cross-shore migration, rotation, and breathing processes at an embayed beach. J Geophys Res-Earth Surf 122(10):1745–1770. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017jf004227

-

Bollen M, Battershill CN, Pilditch CA, Bischof K (2017) Desiccation tolerance of different life stages of the invasive marine kelp Undaria pinnatifida: potential for overland transport as invasion vector. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 496:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2017.07.005

-

Bozeman B, Boardman C (2014) Research collaboration and team science: a state-of-the-art review and agenda. Springer

-

Brandt P, Ernst A, Gralla F, Luederitz C, Lang DJ, Newig J, Reinert F, Abson DJ, von Wehrden H (2013) A review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science. Ecol Econ 92:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.04.008

-

Brewer GD (1999) The challenges of interdisciplinarity. Policy Sci 32(4):327–337. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004706019826

-

Bromham L, Dinnage R, Hua X (2016) Interdisciplinary research has consistently lower funding success. Nature 534(7609):684–687. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18315

-

Brown RR, Deletic A, Wong TH (2015) Interdisciplinarity: how to catalyse collaboration. Nat News 525(7569):315. https://doi.org/10.1038/525315a

-

Bruce A, Lyall C, Tait J, Williams R (2004) Interdisciplinary integration in Europe: the case of the Fifth Framework programme. Futures 36(4):457–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2003.10.003

-

BSH (2014) Standard Baugrunderkundung: Mindestanforderungen an die Baugrunderkundung und-untersuchung für Offshore-Windenergieanlagen. Offshore-Stationen und Stromkabel Bundesamt für Seeschifffahrt und Hydrographie

-

Campbell LM (2005) Overcoming obstacles to interdisciplinary research. Conserv Biol 19(2):574–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00058.x

-

Carew AL, Wickson F (2010) The TD Wheel: a heuristic to shape, support and evaluate transdisciplinary research. Futures 42(10):1146–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2010.04.025

-

Desholm M, Kahlert J (2005) Avian collision risk at an offshore wind farm. Biol Lett 1(3):296–298. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2005.0336

-

Deutscher Bundestag (2014) Gesetz für den Ausbau erneuerbarer Energien (Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz–EEG 2014). EEG, Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I. Deutscher Bundestag, pp. 1066–1132

-

Devine-Wright P, Howes Y (2010) Disruption to place attachment and the protection of restorative environments: a wind energy case study. J Environ Psychol 30(3):271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.008

-

Devlin E (2005) Factors affecting public acceptance of wind turbines in Sweden. Wind Eng 29(6):503–511. https://doi.org/10.1260/030952405776234580

-

Eigenbrode SD, O’Rourke M, Wulfhorst JD, Althoff DM, Goldberg CS, Merrill K, Morse W, Nielsen-Pincus M, Stephens J, Winowiecki L, Bosque-Perez NA (2007) Employing philosophical dialogue in collaborative science. Bioscience 57(1):55–64. https://doi.org/10.1641/B570109

-

Elmer K, Gerasch W, Neumann T, Gabriel J, Betke K, Glahn M (2007) Measurement and reduction of offshore wind turbine construction noise. DEWI Mag 30:1–6

-

Ender C (2017) Wind energy use in Germany—status 31.12.2016. DEWI Mag 50:38–40

-

Gee K (2010) Offshore wind power development as affected by seascape values on the German North Sea coast. Land Use Policy 27(2):185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.05.003

-

Gewin V (2014) Interdisciplinary research: break out. Nature 511(7509):371–373. https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7509-371a

-

Goring SJ, Weathers KC, Dodds WK, Soranno PA, Sweet LC, Cheruvelil KS, Kominoski JS, Ruegg J, Thorn AM, Utz RM (2014) Improving the culture of interdisciplinary collaboration in ecology by expanding measures of success. Front Ecol Environ 12(1):39–47. https://doi.org/10.1890/120370

-

Graybill JK, Dooling S, Shandas V, Withey J, Greve A, Simon GL(2006) A rough guide to interdisciplinarity: graduate student perspectives Bioscience 56(9):757–763. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[757:Argtig]2.0.Co;2

-

Hansen MT, Von Oetinger B (2001) Introducing T-shaped managers: knowledge management’s next generation. Harvard Bus Rev 79(3):106–117

-

Hübner G, Pohl J (2016) Aus den Augen, aus dem Sinn? Meer–wind–strom. Springer, pp. 225–234

-

Hübner G, Pohl J (2014) Akzeptanz der Offshore-Windenergienutzung: Abschlussbericht; Forschungsinitiative RAVE—Research at alpha ventus: Martin-Luther-University. Institute für Psychologie, AG Gesundheits-und Umweltpsychologie, Halle-Wittenberg

-

Hüppop O, Dierschke J, Exo KM, Fredrich E, Hill R (2006) Bird migration studies and potential collision risk with offshore wind turbines. Ibis 148(s1):90–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919x.2006.00536.x

-

Jahn T (2008) Transdisciplinarity in the practice of research. In: Bergmann M, Schramm E eds. Transdisziplinäre Forschung: Integrative Forschungsprozesse verstehen und bewerten. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt/Main, Germany, pp. 21–37

-

Juhl L, Yearsley K, Silva AJ (1997) Interdisciplinary project-based learning through an environmental water quality study. J Chem Educ 74(12):1431–1433. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed074p1431

-

Kempton W, Archer CL, Dhanju A, Garvine RW, Jacobson MZ (2007) Large CO2 reductions via offshore wind power matched to inherent storage in energy end-uses. Geophys Res Lett 34(2). https://doi.org/10.1029/2006gl028016

-

Kennedy C, Baker L, Dhakal S, Ramaswami A (2012) Sustainable urban systems an integrated approach. J Ind Ecol 16(6):775–779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00564.x

-

Kluger MO, Jorat ME, Moon VG, Kreiter S, de Lange WP, Morz T, Robertson T, Lowe DJ (2019) Rainfall threshold for initiating effective stress decrease and failure in weathered tephra slopes. Landslides 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-019-01289-2

-

Kluger MO, Moon VG, Kreiter S, Lowe DJ, Churchman GJ, Hepp DA, Seibel D, Jorat ME, Morz T (2017) A new attraction-detachment model for explaining flow sliding in clay-rich tephras. Geology 45(2):131–134. https://doi.org/10.1130/G38560.1

-

Koschinsky A, Heinrich L, Boehnke K, Cohrs JC, Markus T, Shani M, Singh P, Smith Stegen K, Werner W (2018) Deep-sea mining: interdisciplinary research on potential environmental, legal, economic, and societal implications. Integr Environ Assess Manag 14(6):672–691. https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.4071

-

Krütli P, Stauffacher M, Flüeler T, Scholz RW (2010) Functional‐dynamic public participation in technological decision‐making: site selection processes of nuclear waste repositories. J Risk Res 13(7):861–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669871003703252

-

Kulgemeyer T, Muller H, von Dobeneck T, Bryan KR, de Lange WP, Battershill CN (2017) Magnetic mineral and sediment porosity distribution on a storm-dominated shelf investigated by benthic electromagnetic profiling (Bay of Plenty, New Zealand). Mar Geol 383:78–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2016.11.014

-

Lang DJ, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P, Moll P, Swilling M, Thomas CJ (2012) Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain Sci 7(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x

-

Langfeldt L, Godø H, Gornitzka Å, Kaloudis A (2012) Integration modes in EU research: centrifugality versus coordination of national research policies. Sci Public Policy 39(1):88–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs001

-

Laursen B (2018) What is collaborative, interdisciplinary reasoning? The heart of interdisciplinary team science. Inform Sci 21:075–106. https://doi.org/10.28945/4010

-

Ledford H (2015a) How to solve the world’s biggest problems. Nature 525:308–311. https://doi.org/10.1038/525308a

-

Ledford H (2015b) Team science. Nature 525(7569):308–311. https://doi.org/10.1038/525308a

-

MacLeod M (2018) What makes interdisciplinarity difficult? Some consequences of domain specificity in interdisciplinary practice. Synthese 195(2):697–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1236-4

-

Markus T, Huhn K, Bischof K (2015) The quest for sea-floor integrity. Nat Geosci 8(3):163–164. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2380

-

Mauser W, Klepper G, Rice M, Schmalzbauer BS, Hackmann H, Leemans R, Moore H (2013) Transdisciplinary global change research: the co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 5(3–4):420–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.001

-

McCarthy J (2004) Tackling the challenges of interdisciplinary bioscience. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5(11):933–937. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm1501

-

Menken S, Keestra M (2016) An introduction to interdisciplinary research: theory and practice. Amsterdam University Press

-

Miller TR, Wiek A, Sarewitz D, Robinson J, Olsson L, Kriebel D, Loorbach D (2014) The future of sustainability science: a solutions-oriented research agenda. Sustain Sci 9(2):239–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-013-0224-6

-

Morse WC, Nielsen-Pincus M, Force JE, Wulfhorst JD (2007) Bridges and barriers to developing and conducting interdisciplinary graduate-student team research. Ecol Soc 12(2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267883

-

Morss RE, Wilhelmi OV, Downton MW, Gruntfest E (2005) Flood risk, uncertainty, and scientific information for decision making—lessons from an interdisciplinary project. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 86(11):1593–1601. https://doi.org/10.1175/Bams-86-11-1593

-

Nissani M (1997) Ten cheers for interdisciplinarity: the case for interdisciplinary knowledge and research. Soc Sci J 34(2):201–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0362-3319(97)90051-3

-

Palmer L (2018) Meeting the leadership challenges for interdisciplinary environmental research. Nat Sustain 1(7):330–333. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0103-3

-

Pedersen DB (2016) Integrating social sciences and humanities in interdisciplinary research. Palgrave Commun 2(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.36

-

Pennington DD, Simpson GL, McConnell MS, Fair JM, Baker RJ (2013) Transdisciplinary research, transformative learning, and transformative science. Bioscience 63(7):564–573. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2013.63.7.9

-

Pykett J, Chrisinger B, Kyriakou K, Osborne T, Resch B, Stathi A, Toth E, Whittaker AC (2020) Developing a Citizen Social Science approach to understand urban stress and promote wellbeing in urban communities. Palgrave Commun 6(1):1–11

-

Repko AF, Szostak R (2020) Interdisciplinary research: process and theory. SAGE Publications, Incorporated

-

Rhoten D, Parker A (2004) Risks and rewards of an interdisciplinary research path. Science 306(5704):2046. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103628

-

Rylance R (2015) Grant giving: global funders to focus on interdisciplinarity. Nature 525(7569):313–316. https://doi.org/10.1038/525313a

-

Sá CM (2008) ‘Interdisciplinary strategies’ in US research universities. Higher Educ 55(5):537–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9073-5

-

Scheve J (2017) Der Sicherheitsdiskurs im deutschen Küstenschutz-Hemmnis für eine notwendige Transformation in Zeiten des Klimawandels. Universität Bremen, artec Forschungszentrum Nachhaltigkeit

-

Skates G (2003) Interdisciplinary project working in engineering education. Eur J Eng Educ 28(2):187–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/0304379031000079022

-

Staudt F, Mullarney JC, Pilditch CA, Huhn K (2017) The role of grain-size ratio in the mobility of mixed granular beds. Geomorphology 278, 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.11.015

-

Steel D, Gonnerman C, O’Rourke M (2017) Scientists’ attitudes on science and values: case studies and survey methods in philosophy of science. Stud Hist Philos Sci 63:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2017.04.002

-

Talwar S, Wiek A, Robinson J (2011) User engagement in sustainability research. Sci Public Policy 38(5):379–390. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234211×12960315267615

-

Tauginienė L, Butkevičienė E, Vohland K, Heinisch B, Daskolia M, Suškevičs M, Portela M, Balázs B, Prūse B (2020) Citizen science in the social sciences and humanities: the power of interdisciplinarity. Palgrave Commun 6(1):1–11

-

Van Noorden R (2015) Interdisciplinary research by the numbers. Nature 525(7569):306–308

-

Viseu A (2015) Integration of social science into research is crucial. Nature 525(7569):291–291. https://doi.org/10.1038/525291a

-

Wagner CS, Roessner JD, Bobb K, Klein JT, Boyack KW, Keyton J, Rafols I, Börner K (2011) Approaches to understanding and measuring interdisciplinary scientific research (IDR): a review of the literature. J Inform 5(1):14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.06.004

-

Welch-Devine M (2012) Searching for success: defining success in co-management. Hum Organ 71(4):358–370. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.71.4.y048347510304870

-

Welch-Devine M, Campbell LM (2010) Sorting out roles and defining divides: social sciences at the World Conservation Congress. Conserv Soc 8(4):339. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26393024

-

Wolsink M (2007) Wind power implementation: the nature of public attitudes: equity and fairness instead of ‘backyard motives’. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 11(6):1188–1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2005.10.005