1 Introduction

Welcome to the rheumatology portion of your MJBS course. We hope you enjoy this chance to learn about some of the main kinds of diseases and problems treated by rheumatologists.

Why is learning rheumatology important? Musculoskeletal complaints are common in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. Recent studies indicate that close to 19% of adults 18 and older in the United States have a physician-diagnosed form of arthritis, one of the primary problems treated by rheumatologists. (See Figure below).

Although not as common, arthritis can affect children as well, with an estimated 1/1,000 kids under 16 in the US affected by forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

Although not as common, arthritis can affect children as well, with an estimated 1/1,000 kids under 16 in the US affected by forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

Not all of these patients need to be seen by a rheumatologist. Internal medicine, family physicians, orthopedic and sport medicine specialists often care for patients with osteoarthritis and common crystalline arthropathies (gout) for example. However, differentiating those patients with more chronic inflammatory or immune-mediated joint and systemic diseases is particularly important as these conditions require very different treatment approaches to improve outcomes and prevent morbidity and mortality. There is currently a shortage of rheumatologists in the US and with our aging population, the demand is expected to increase. In the field of pediatric rheumatology in particular, there are only approximately 350 practicing providers nationwide leaving entire states, including AK in our WWAMI region, without access to subspecialty care.

One of the challenges historically faced by rheumatology is the vague nature of the complaints and conditions treated by the field. Most of the conditions seen by rheumatologists involve aberrant immune responses resulting in musculoskeletal complaints. However, the exact ‘list’ of diseases seen by rheumatologists is somewhat arbitrary and based on historical practices. The underlying trigger or cause for many of these conditions is still often poorly understood, which, in turn, often makes these diseases harder to diagnose. As you will see in this unit, most rheumatologic diseases are clinical diagnoses, meaning that there is no one lab test or finding that allows for definitive diagnosis. Given this, much of the work of rheumatology involves careful pattern description. Over time, different patterns of disease presentation, evolution, and associated lab and radiographic findings have been used to create a framework of diagnostic categories. Often, as we learn more about these different diseases through modern advances in immunology and genetics, we are finding new ways of categorizing and describing these disorders, which can lead to confusing nomenclature changes.

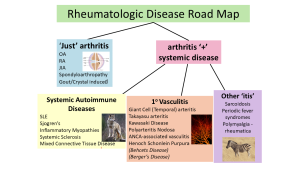

One important thing to remember is that arthritis is a key feature of most of the diseases treated by rheumatologists. Because disease presentations can be variable, not all patients with rheumatologic diagnoses will have arthritis at presentation. However, arthritis can be seen in almost any diagnosis treated by rheumatologists. Below is a ‘road map’ for this section of the course showing an overview of the various diseases we will be covering in MJBS. One of the first branch points on the map is thinking about diseases that primarily present with joint complaints (referred to as ‘primary arthritis’). As you will see, even these primarily joint-centric disorders can have extra-articular manifestations, however, often the joint complaints are first and foremost. The second branch point refers to diseases that tend to have more systemic involvement (arthritis + systemic disease).

Disclaimer: This map isn’t based on biology but is one framework to sort the different diseases into broader groups of related disorders. Hopefully this type of concept mapping is a useful tool to help you organize your thoughts and will help with memorization and retention.