3 Overview of Arthritis and Synovial Fluid Composition

The term “arthritis” describes a large family of disorders that occur in synovial joints. The term arthritis itself is non-specific and can refer to any of a number of different types of processes that lead to inflammation of the joint and surrounding structures. Thus arthritis may be infectious (‘septic’ arthritis), degenerative/mechanical (eg. osteoarthritis, traumatic arthritis) or immune-mediated. Immune-mediated arthritis can be further divided into autoinflammatory causes (eg. crystalline arthropathies such as gout) versus autoimmune diseases (eg. Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis). In this course we will focus on chronic, non-infectious causes of arthritis but it is important to remember that pathogens such as bacteria or viruses can cause acute or subacute infections of the joints and soft tissues. Immune-mediated arthritis is always a diagnosis of exclusion! Mono-articular (ie. involvement of one joint) arthritis should in particular prompt a thorough evaluation for infectious causes. (Pathogens that exist on epithelial surfaces like staphylococcus and streptococcus are less likely to be able to seed multiple joints simultaneously unless a patient has been bacteremic and thus often septic/severely ill).

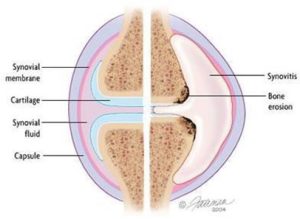

Most forms of arthritis are characterized more specifically by synovitis, or inflammation of the synovial lining of the joint. As you learned earlier in the block, the synovial lining (also known as synovium) is responsible for the production of joint fluid. (See Figure) Normally the amount of fluid produced is just enough to provide a thin lubricating layer between the articular surfaces of the bones. However, in response to a variety of insults (infection, inflammation/autoimmune response, crystals in the joint, increased blood flow near the joint, increased friction in the joint, and sometimes for reasons we don’t understand) the synovium will increase its production of fluid rather nonspecifically.

Thinking back to the principles covered in the I&I block, inflammation is a cascade of events, mediated by immune cells and cell signals such as cytokines (especially TNF-alpha, IL-1 and IL-6) and chemokines (CCX) that bring in neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes), and other cells to a particular site. This may be because of injury, the presence of foreign proteins, or because of a confused immune response against self-antigens.

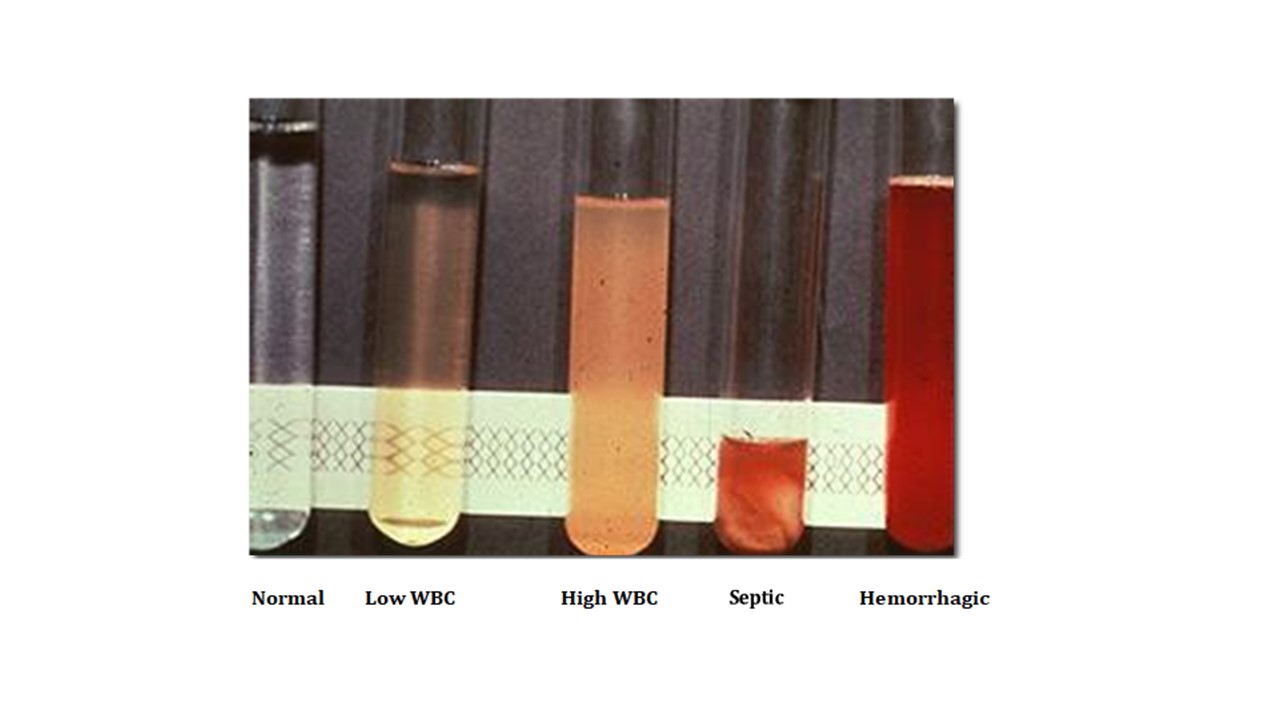

An increased amount of joint fluid is called an effusion. Different kinds of arthritis may present with effusions and/or synovitis. In a normal joint, synovial fluid is viscous, transparent and straw colored. In a healthy joint, it contains less than 2,000 white blood cells/mm3, the majority of which are mononuclear (lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages). Analysis of the synovial fluid can be a useful starting point to help evaluate the etiology of an effusion. Fluid can be extracted from a joint by inserting a sterile needle into the joint and removing fluid into a syringe (arthrocentesis). Often the appearance of the fluid removed alone can provide clues as to the etiology of the joint pathology, as shown in the figure. This fluid can be sent to the laboratory for more directed testing, including cell count, gram stain and culture, and analysis for presence of crystals.

An increased amount of joint fluid is called an effusion. Different kinds of arthritis may present with effusions and/or synovitis. In a normal joint, synovial fluid is viscous, transparent and straw colored. In a healthy joint, it contains less than 2,000 white blood cells/mm3, the majority of which are mononuclear (lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages). Analysis of the synovial fluid can be a useful starting point to help evaluate the etiology of an effusion. Fluid can be extracted from a joint by inserting a sterile needle into the joint and removing fluid into a syringe (arthrocentesis). Often the appearance of the fluid removed alone can provide clues as to the etiology of the joint pathology, as shown in the figure. This fluid can be sent to the laboratory for more directed testing, including cell count, gram stain and culture, and analysis for presence of crystals.

The table below provides guidelines of the range in number and types of leukocytes detected in effusions in various clinical scenarios. For example, when the fluid contains more than 100,000 white cells/mm3, there should be high concern that the joint is acutely infected with a bacterial pathogen. Similarly, when greater than 95% of the white cells are polymorphonuclear, acute infection is also more likely. Cell counts between 50,000 and 100,000 are less helpful diagnostically as they may represent inflammation or infection. These are general rules, however and there may be considerable overlap between different categories of joint pathologies so one must consider the clinical situation when interpreting results.

|

Fluid Type |

Clarity |

WBC count (cells/mm3) |

% PMN’s |

|

Normal |

transparent |

200 |

< 25 |

|

Non-inflammatory (eg. OA) |

transparent |

<2,000 |

< 25 |

|

Inflammatory (eg. RA) |

translucent |

< 75,000 |

>25-50 |

|

Septic* (acute bacterial infection) |

opaque |

> 75,000 |

> 75 |

*Note: Septic joints may have < 75,000 cells/mm3 and certain inflammatory diseases (i.e. gout) may have > 75,000 cell /mm3

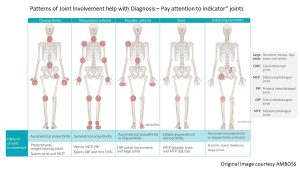

Distribution = Differential Diagnosis!

Another key feature which can help in determining the type of disease responsible for joint complaints is the pattern and distribution of joints that are affected. Certain kinds of arthritis tend to affect different sizes of joints. Some can be more symmetric while others tend to be more random or ‘patchy.’ The number and specific joints affected can also give clues as to the type of arthritis which may be most likely. Below are a list of characteristics to consider when synthesizing a patients presentation.

# of affected joints:

- mono-articular – one joint

- oligo-articular: ‘few’ joints – somewhat arbitrary but generally 4 or less (aka. pauci-articular)

- poly-articular: ‘many’ joints – 5 or more affected joints

Type/location of joints:

- Size – small (Fingers/toes) medium (wrist, elbows, ankles) versus large (hips, knees, shoulder)

- Region – Axial (ie spine, sacroiliac joints) versus peripheral

- Symmetry – bilateral/symmetric versus asymmetric/patchy

Specific ‘Indicator’ Joints:

More on this in the chronic joint sessions but certain joints like sacroiliac, distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint, carpometacarpal (CMC) joints etc are classically affected in certain diseases and not others.