Data Visualization

One of the most sought-after skills in any career that uses information is visualization. Data visualization helps us simplify complex data sets, tell a story, and can even be used as a tool for discovery and analysis. Data visualization is, as the name would suggest, the visual display of data. It’s a critical skill for working with information because we humans are specially designed to take in and process information visually. Our brains have evolved to be awesome at seeing patterns in visual things. We learned that certain patterns on animals equal danger, we learned that colors indicate when food is good to eat, and we got really good at judging heights and distances visually as we learned to navigate the physical world. You show us something visually and our brains instinctively look for meaning in it. Because of this, when you want to share data findings with others or find something in the data yourself, data visualization is one of the more powerful to go about it.

Data Visualization for Storytelling

We already talked about the importance of data storytelling in a people analytics career in “Step 2. Build Your Non-Technical Skills” and data visualization is one of the best tools we have for doing data-driven storytelling. Think of being a little kid, wouldn’t you want a storybook with pictures? Our people data storytelling is no different. Visuals can help the story be stronger, clearer, and more engaging. A well-designed chart or graph can instantly communicate complex information in a way that text often can’t. Visuals can help capture attention, highlight key findings, and make your story more memorable and impactful.

In addition to all these great things, they allow you to share information faster than using words alone. For example, it can take quite a few words to explain how trends in employee satisfaction scores have changed over time but a line chart tells that story in a matter of seconds. This leaves more time to discuss what happened and what to do about it. I don’t know about you, but I would much rather spend time designing ways to improve the employee experience than trying to explain the numbers.

Data visualizations can spark curiosity and encourage deeper exploration of people data. Back in my day (yes, I am “old” enough in the people analytics field to say that), there was limited interest in people analytics. The term ‘people analytics’ didn’t even exist yet, so few people were aware of it, and even fewer were asking for it. But, a data visualization could draw interest and almost always drew more questions and requests for additional insights. For instance, let’s say you were doing analytics on employee attrition – a relatively common topic and requested measurement. Simply stating that “Department X had an increase in attrition” doesn’t capture much attention. The response might be, “yeah, we know, Jeremiah left last week and Preeti left last month.” But, if that department’s spike in attrition was shown on a heatmap compared to other departments where they stood out as being much higher than others, it might prompt more reactions and questions. The comments then change to questions like, “Is our attrition really that much higher than everyone else? What is going on in our department?” which leads to further investigation and potential solutions. By incorporating compelling visuals into your stories, you engage others in conversations about people analytics insights that are more meaningful and action-oriented.

“Visualization gives you answers to questions you didn’t know you had.” – Ben Schneiderman

Data visualization is not just for quantitative data. Because qualitative data is still less frequently used, visuals can be even more important to tell your qualitative data story. They can help your audience understand the key findings and even give some additional credibility and support to your analysis process. In the world of people analytics, you might use visuals like mind maps to show the structure or relationship between analyzed codes and themes (e.g., different types of employee concerns). You might visually display areas of contrasting findings. For example, let’s say you assessed the effectiveness of a training program by interviewing employees about their ability to apply the trained skills to their work. A heatmap could show each skill colored-coded by a subjective assessment, highlighting which skills the training taught effectively and which trainings need to be improved. Other times, you don’t just find themes, groupings, or differences. Sometimes you find flows, structure, and ordering. Luckily, visualizations are fantastic at representing processes and structure. You can use visuals to show the order of more intangible events and things that tend to follow a pattern in your organization. For example, you could display commonly occurring career pathways using process or flow diagrams. Using a visual can showcase things harder to quantitatively measure such as the transferable skills that lead to career flexibility. Remember that qualitative data isn’t limited to things like text from employee surveys or interviews nor do the visuals need to be limited to charts and graphs. A fantastic qualitative analysis and corresponding visual might come from observation or diary studies that are analyzed and then put into a visual to show the process and flow of how employees experience a day of interacting with work systems, or the employee lifecycle at a company.

Tip: Sometimes qualitative data itself can be used as a visual that adds more information and a human element to your work. For example, if you display a quantitative chart that highlights a high employee engagement rate on a graph, you can also add a textbox with an employee quote saying what they love about the company. It’s a powerful way to emphasize the human experience and add the qualitative story visually along with the quantitative data story.

Finally, when telling your story, keep in mind that it is a story and is therefore meant to be an experience. Don’t limit yourself and get creative. You aren’t limited to only numerical, text, or process-based data. You can make maps for non-text data (e.g., group images together, or play video clips in a media compilation). If you work in a physical space, you can even use physical objects. Who knows, maybe when you need to do that presentation including a statistic about the troubling 10% rate of safety incidents on the job sites, you’ll skip the PowerPoint chart and instead choose to line up 9 perfectly in-tact safety helmets followed by one horribly damaged helmet on the table in front of you as you stress the need for better safety training and compliance.

“Don’t transfer information, create an experience.” – Nancy Duarte

Data Visualization for Reporting & Sharing

Did you know that reports, dashboards, scorecards, and any other mechanism you use to share data are all examples of data visualizations? For example, let’s say you are asked to provide a regular report on absenteeism. First, you have to decide what you will provide: will absenteeism be shown as a count, ratio, or percentage? Will you give an overall number or display the values for each department or location separately? Will it be for one period of time or over multiple periods? These questions form the basis for the report, then there are still questions about how you will provide it. Will the values all be provided together in a single table? Will they be shown in a chart occurring over time? Will it need formatting like bolding of key metrics, or color to highlight positive or negative trends? Will it need clear and concise labels to help people quickly scan and understand the report? Will the report be static or hosted on a website with animation or the ability to switch between different subsets of data? Is there an absenteeism level the company deems ‘acceptable’ that needs to be incorporated as a reference so leaders can interpret the current rate relative to the acceptable rate?

Effective sharing of data requires thoughtful visual design principles to provide businesses with the information needed to navigate complex information and make decisions. This applies whether we are talking about static reporting in the form of manually created scorecards, reports, or presentations. And it applies even to the reports that we “automatically” generate out of information systems (e.g., the ones produced by an HR Information System). If you are going into a data system and selecting the values, calculations, and layout of the report to be generated, you are making visualization choices. Whether that is a simple reporting tool or a complex business intelligence system. If the goal is to present information, data visualization is necessary to achieve that goal.

Every decision made about what to show and how to show it is a data visualization decision. Even whether to create a visual or not is a data visualization decision. Which brings up an important point, not all data needs to have a story or be visualized. What if the person asking for that absenteeism report only needed to know the current rate to answer a simple question and they are unlikely to ask for that information again in the future? It may not be worth the time or effort to make a report or design visuals. It may be best to calculate the rate and tell them the result, saving you the time of making a report and helping them answer their question quicker. It’s also true that there are just some things that aren’t represented well visually. Sometimes it is better to use words or numbers and sometimes the context or situation isn’t appropriate for including visualizations. Use visualizations, but use them when they support and enhance your goals.

Speaking of things not everyone realizes about data visualization, not all data visualizations are charts, graphs, or diagrams. Sometimes the best data visualizations come from applying visual design principles to things like words, images, or even just a single numerical value. A text-based report with a single metric in a font 4 times larger than the rest of the text can have a tremendous impact. A key theme from a qualitative analysis bolded for emphasis can draw attention where needed. Even the placement of items on a screen or page impacts how effectively others understand your findings. Data visualization is about helping your audience see what is important to be seen.

Accessibility is key.

When building data visualizations, ensure everyone, including people with different visual abilities, can access the full story of your data. This means considering viewers who might have different color perspectives, sizing, and contrast needs, or who may rely on screen readers or assistive technologies.

Use high-contrast color palettes and avoid relying solely on color to differentiate data points. Opt for charts with clear patterns over complex 3D designs. Use concise labels and consider including text descriptions within the visualization itself. If you’re creating web-based dashboards or interfaces, always provide alternative text descriptions that explain the purpose of the visual and summarize the data and trends represented for screen readers to capture. Take some time to review and follow data visualization accessibility standards (e.g., the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, or WCAG) to help you do this well.

Data Visualization for Analysis & Discovery

Visualization isn’t just for sharing information with other people. In fact, data visualization is one of my favorite techniques for doing analysis. It’s one of the first things I do when analyzing a new data set. Some things are too difficult or impossible to see in raw data or through statistical approaches, yet they seem to magically ‘pop out’ with the right visual. And, some things are just easier to see visually. Visuals can be a quick way to spot outliers, anomalies, and data issues. Often discrepancies, patterns, or groupings visible in an image can inform my entire approach to cleaning, analyzing, or interpreting data. Data visualization tools that allow for quick creation of visuals (e.g., Tableau, PowerBI, Excel) can make the creation of these types of visuals sometimes as fast as or faster than calculating the statistics. You can use visualization to conduct exploratory analyses or directly answer some of the same questions you might approach using descriptive, diagnostic, predictive, and prescriptive analytics.

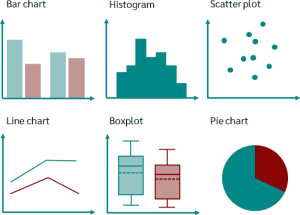

Take, for example, a manager wanting a detailed understanding of performance ratings for the employees they supervise. Statistics shown as numbers may not be as helpful to them as what they could learn from visuals. Here are some examples of things they might be able to learn from different types of visuals. Looking at the distribution of performance ratings on a frequency chart would more quickly allow them to see how many employees are rated on the high or low end of performance; bar charts, histograms, and pie charts also help do this quickly. Creating scatterplots, histograms, or boxplots could give a quick visualization of the distribution, spread, and relationship of ratings among the employees. Visuals could show comparisons of performance distributions across job types, experience levels, or demographics to identify variations and address any group-specific concerns. A line chart could show performance changes over time. They could use scatterplots to identify possible relationships between factors; for example, the manager may wish to know whether performance ratings connect with other factors like tenure, training completion, or specific skills. A scatterplot showing what appears to be a straight line of data points with performance on one axis and training completion on the other may highlight a possible correlation in which more training appears to be related to higher performance. Boxplots can make spotting outliers a breeze – spotting outliers can be very difficult to see when only looking at raw data. And, scatterplots can show those outliers in relation to other variables, providing an opportunity to assess whether the outlier is problematic or an important unique piece of data. For example, if the manager spotted an outlier they could look at it to see if it was a data entry error that needed to be fixed or if it is highlighting an exceptionally well-performing employee that deserves to be recognized and celebrated. With a mix of visuals the manager could get a holistic sense of how performance is occurring, how it is related to various aspects, and where they might want to explore the data further.

When You Need to Explain How You Did Your Qualitative Analysis – Consider Using Visualizations

Clearly, visualizations are great for many things – I’ve already talked about how they support our storytelling, help us transfer information better, and how we can even use them to conduct analyses. An additional thing they are great for is helping in those times when you need to explain to others how you did your people analytics work. As a disclaimer, I will usually warn that I do not usually advise that you share many details of exactly how you have done all of your analyses unless you have been asked or you know your audience expects that information. I’ve found that most people don’t want to hear the full process of how you got to your findings – especially your quantitative analyses. (More on that in “Step 4. Share Insights and Build Relationships” where we talk about sharing your findings.) However, you may be asked. And, I actually do encourage the opposite when it comes to qualitative analysis.

Because most people are unfamiliar with true qualitative analysis and because there is an erroneous misconception that it is not as “rigorous,” as quantitative methods, your audience needs to be shown how rigorous your process was so they can trust the results. Unfortunately, explaining qualitative analytics techniques is extraordinarily difficult. So, instead of forcing your audience to sit through a lecture about research methodology, I encourage you to “show your work” for qualitative analysis using visuals at various steps of your process.

As mentioned earlier, visuals are great for explaining complex things and especially for workflows and processes. So, for example, you may want to show them how you took a massive and messy unstructured data set and transformed it into your key takeaways and insights. You could do this by providing an image of some of the anonymized interview transcript text you used with different selections of the text color-coded if you wanted them to understand how you took individual employee comments and did a coding technique to find key themes. In general, data visualizations should be as simple and clean as possible, but I personally think this is one place where you may want to break the rules a little bit. Feel free to overwhelm your audience a little bit here, just so they understand the depth, complexity, and volume of information you have sifted through. Show them the effort and rigor, and give them a sense of the systematic and intentional way the results were formed. Just don’t make them look at all of your data, an example should be enough (e.g., a screenshot, or anonymized sample subset), and make sure that you are not sharing anything private or confidential. Any visual that can help give your audience a sense of the process that displays the rigor of analysis will be powerful evidence that your results are true analytics not just an opinion.

No art skills required!

I suck at drawing. I can’t sing, act, or play an instrument. I have no idea how people turn clay, wood, paint, or metal into objects, let alone into abstract art. I can’t seem to figure out how to match items of clothing together. My idea of decorating is a calendar thumbtacked to the wall. What I am trying to say is that I am not the person you call if you need something to look ‘pretty.’ But I did learn how to make good data visualizations. That’s because effective data visualization isn’t about making information look pretty. It’s about clarity, conciseness, and accuracy. It’s about presenting data in a way that supports informed decision-making.

Some data visualizations are exceptionally beautiful. For those who have an interest in people analytics, a creative side, and an interest in visual design or just a desire to put some art and beauty into your work – data visualization could be an amazingly satisfying area for you to play in. You’ll love all the wonderful things you can do. But, if you don’t usually think of yourself as someone who gravitates toward art, creativity, or aesthetics, don’t worry. You don’t have to be an artist, and you don’t have to be a ‘creative’ person. You can learn basic design principles like color theory, composition, and white space and then apply them. You can use templates or tools and you can mirror the wonderful work of others. Data visualization is a skill that can be learned. Data visualization gives us all a chance to be an artist.

Compare things with bars of different lengths.

Show how a whole is divided into parts.

Show relationships between two things. (Like dots scattered across a graph)

Show how many data points fall within certain ranges. (Bars where the different bar height represents the amount of data points at that value)

Show the spread of data with a box and whiskers. (The line in the middle is the median, splitting the data with 50% above and below. The box edges represent the first and third quartiles (Q1 & Q3). 25% of data lies below the box and 25% above. The width of the box shows how spread out the middle 50% of data is. Dots outside the box may be potential outliers.

Show how something changes over time.