23 Patient C

This patient case is adapted from a published case in the New England Journal of Medicine:

MacDonald, S.M. et al (2016) “Case 32-2016–A 20-Year-Old Man with Gynecomastia” New England Journal of Medicine 375: 1567-1579

Quotes from the text of the paper are presented as blockquotes in dark blue bold face. Questions are presented periodically, which you should try to answer yourself before clicking to see the response. In a quiz section test, you will be expected to be able to answer these questions, as well as being able to identify terms in purple bold face.

Note that this paper was published in 2016. In 2022, a worldwide working group of endocrinologists published a position statement proposing that the name “diabetes insipidus” be changed to arginine vasopressin deficiency (AVP-D) for central diabetes insipidus and arginine vasopressin resistance (AVP-R) for nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. This change was proposed to prevent treatment errors by health providers that might confuse disorders of vasopressin action (i.e. “diabetes insipidus”) with diabetes mellitus. I have left the term “diabetes insipidus” in the quotes from the doctor that are taken directly from the paper, but have tried to use the preferred new names where possible.

The patient came to the hospital for a routine annual examination to establish adult care. He reported a 3-year history of bilateral breast enlargement, with no nipple discharge.

…Approximately 4 years before this evaluation, increased thirst and fluid consumption and frequent urination (four to five times during the day and up to three times each night) had developed. The patient’s parents reportedly worried that he might have diabetes, but a urinary glucose screen was negative and further evaluation was not pursued.

In recent months, the frequency of urination had decreased and thirst was normal. He also reported a several-year history of blurred vision, which had been corrected with glasses; he had no diplopia and had occasional headaches after exertion. Puberty was reportedly normal. Approximately 8 months before this presentation, he started to experience symptoms related to decreased testosterone secretion.

On examination, the patient appeared young for his age, with minimal facial hair. The blood pressure was 98/62 mm Hg; the other vital signs were normal. The height was 179 cm, the weight 85 kg, and the body-mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) 26.5. Both breasts were enlarged, with no nipple retraction, masses, or discharge. The testicles were small (approximately 2.5 cm in length).

This patient is experiencing breast enlargement (gynocomastia), lack of facial hair growth and small testicular volume, all of which suggest decreased testosterone secretion. Testosterone is the male sex hormone, responsible for stimulating spermatogenesis in the testis and the development of male secondary sexual characteristics such as the growth of facial hair. Breast growth, which is a female secondary sexual characteristic dependent on estrogen, is usually prevented in males by high levels of testosterone secretion.

Low testosterone secretion could be due to a defect in the testes, or a defect in the regulation of testosterone secretion. Testosterone secretion is regulated by hormones that are released from the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary.

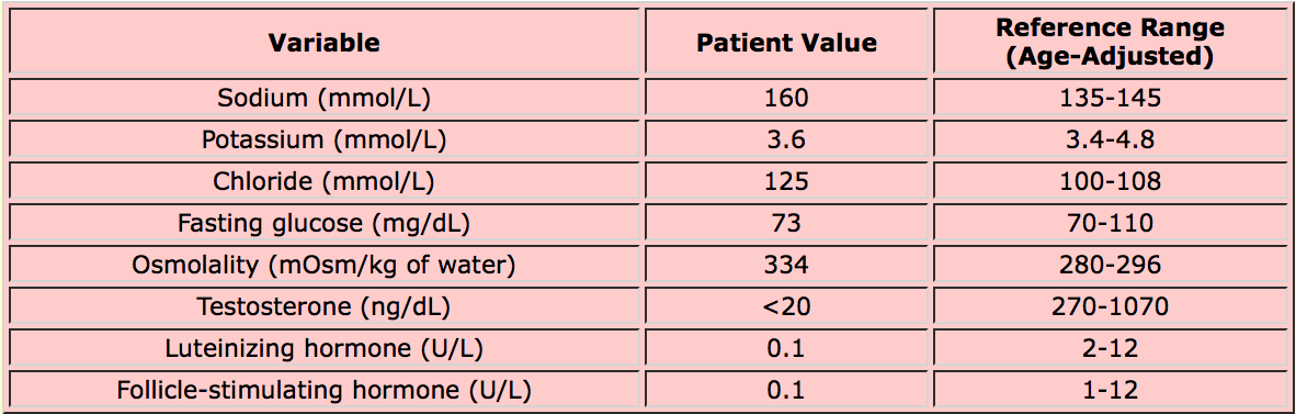

Urinalysis was normal. Additional diagnostic blood tests were performed. Important test results are presented in the table below.

The test results show that the patient’s hypogonadism (low testosterone secretion) is due to much lower than normal secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), anterior pituitary hormones that are collectively called the gonadotropins because they stimulate testosterone secretion. As well, the tests show an increase in plasma osmolality.

(Osmolality, like osmolarity, is a measure of the osmotic activity of a fluid. Osmolality measures the amount of solute per kilogram of solvent, osmolarity measures the amount of solute per liter of solution. For physiological solutions, osmolarity and osmolality are very similar. Osmolality is used in clinical situations because clinical osmometers measure osmolality.)

The doctor’s comment:

One more piece of the patient’s history offers an important clue that could help to discriminate among different causes of hypogonadism. The patient had a 4-year history of polyuria and polydipsia (increased thirst) that had recently started to resolve. Diabetes mellitus was considered and ruled out; however, diabetes insipidus was not. Diabetes insipidus is caused by a loss of the action of vasopressin on the renal collecting duct to reabsorb water.

The doctor’s comments continue:

Diabetes insipidus is typically associated with increased thirst in response to rising hypertonicity. If adequate fluids are available, the serum osmolality is rarely substantially higher than the normal range. This patient’s serum sodium level and osmolality were quite high (see table above); these findings, combined with a lack of polydipsia, raise concerns about an unusual condition known as adipsic diabetes insipidus.

“Adipsic” means lacking thirst. Adipsia occurs because of dysfunction in the hypothalamic osmoreceptors.

The patient was found to have a germinoma (a type of tumor) which was located in the suprasellar region, an area of the hypothalamus directly above the pituitary gland. The patient’s symptoms occurred because the tumor compromised the function of three key cell types located in that part of the hypothalamus:

- neurosecretory cells releasing vasopressin

- hypothalamic osmoreceptors that stimulate thirst and vasopressin secretion

- neurosecretory cells that release a hormone (gonadotropin releasing hormone; GnRH) that stimulates FSH and LH secretion (low FSH and LH secretion are what caused the low testosterone secretion).

The patient had surgery, followed by chemotherapy and radiation to fully eliminate the tumor. His hypogonadism was treated with testosterone supplementation. His high serum osmolality was treated with desmopressin, a vasopressin agonist that specifically binds to the V2 vasopressin receptors in the kidney.

…[The patient was initially] discharged with guidelines that specified how much fluid he should drink daily, since he did not have appropriate thirst. This regimen was accompanied by frequent laboratory checks to monitor sodium levels…Partial thirst returned approximately 1 year after treatment of the germinoma; the patient began reporting a sense of thirst when he had a high-normal or slightly high sodium level, and thus he was allowed to drink in response to thirst instead of using the prescribed fluid guidelines. His sodium level is now well controlled with daily desmopressin.

Below is a summary of the key points in this patient case.

- The patient presented with hypogonadism (low testosterone secretion). His history was notable for a previous episode of polyuria (increased urine volume) and polydipsia (increased thirst).

-

Blood tests were performed to determine the cause of hypogonadism. These revealed that the patient had secondary hypogonadism due to low secretion of FSH and LH. These tests also revealed that the patient had abnormally high plasma osmolality.

- The doctor suspected that the high plasma osmolality was due to diabetes insipidus, now called arginine vasopressin deficiency (AVP-D) or arginine vasopressin resistance (AVP-R). In AVP-D or AVP-R, large volumes of dilute urine are produced due to a defect in the action of vasopressin on the kidney collecting duct.

-

Patients with AVP-D or AVP-R do not normally have high plasma osmolality because thirst drives them to consume more fluid and compensate for the inability to produce concentrated urine. The diagnosis in this case was adipsic AVP-D. The patient had a tumor in the hypothalamus that compromised the function of three types of cells: osmoreceptors, neurosecretory cells that secrete vasopressin, and neurosecretory cells secreting GnRH (a hormone that regulates FSH and LH secretion from the anterior pituitary).

Optional

Here is the article that discusses the proposed name change for diabetes insipidus:

Arima, H. et al. (2022) “Changing the Name of Diabetes Insipidus: A Position Statement of the Working Group for Renaming Diabetes Insipidus” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 108: 1-3