3 Epithelial Transport

Introduction

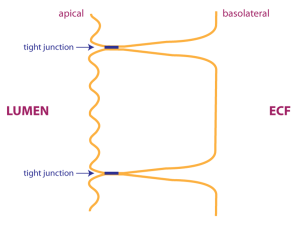

Epithelia form linings throughout the body. In the small intestine, for instance, the simple columnar epithelium forms a barrier that separates the lumen (inside of an organ) from the internal environment of the body. (The internal environment in which body cells exist is the extracellular fluid or ECF). The epithelium forms a barrier because cells are linked by tight junctions, which prevent many substances from diffusing between adjacent cells. For a substance to cross the epithelium, it must be transported across the cell’s plasma membranes by membrane transporters.

Not only do tight junctions limit the flow of substances between cells, they also define compartments in the plasma membrane. The apical plasma membrane faces the lumen. In the drawing, the apical plasma membrane is drawn as a wavy line, because intestinal epithelial cells have a high degree of apical plasma membrane folding to increase the surface area available for membrane transport (these apical plasma membrane folds are known as microvilli). The basolateral plasma membrane faces the ECF. Epithelial cells are able to transport substances in one direction because different sets of transporters are localized in either the apical or basolateral membranes.

Not only do tight junctions limit the flow of substances between cells, they also define compartments in the plasma membrane. The apical plasma membrane faces the lumen. In the drawing, the apical plasma membrane is drawn as a wavy line, because intestinal epithelial cells have a high degree of apical plasma membrane folding to increase the surface area available for membrane transport (these apical plasma membrane folds are known as microvilli). The basolateral plasma membrane faces the ECF. Epithelial cells are able to transport substances in one direction because different sets of transporters are localized in either the apical or basolateral membranes.

Absorption of Glucose

Absorption is the means whereby nutrients such as glucose are taken into the body to nourish cells. We are using glucose absorption as our specific example; however other sugars and amino acids are absorbed using a similar mechanism (but with different specific transporters).

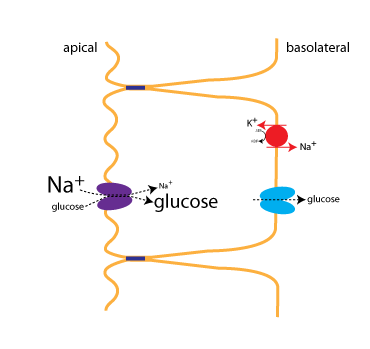

Glucose is transported across the apical plasma membrane of intestinal epithelial cells by the sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT, purple protein in the figure below). Transport via the sodium-glucose cotransporter is referred to as secondary active transport because transport depends upon the Na+ gradient (which is established using the energy of ATP hydrolysis).

Just after a meal, there will be abundant glucose in the lumen of the intestine, favoring absorption. Towards the end of the absorptive phase of a meal, however, the cotransporter is still able to move glucose into the cell (uphill against its concentration gradient) because of the strong Na+concentration gradient. This is what is depicted in the figure, where the size of the type for Na+ and glucose indicates their relative concentrations.

The Na+ gradient is established through active transport by the Na+/K+-ATPase (red), which is located on the basolateral membrane. The activity of the cotransporter increases the glucose concentration inside the cells, allowing glucose to be transported into the ECF via the glucose transporter (GLUT,blue). Facilitated diffusion of glucose into the ECF is a passive process, since glucose flows down its concentration gradient.

Secretion of Fluid

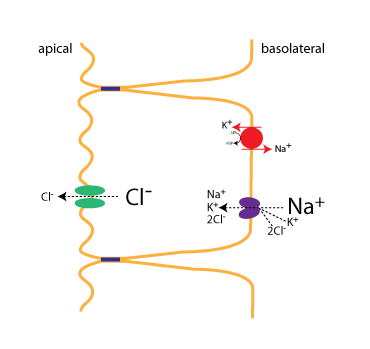

About 1500 ml of fluid per day is secreted into the lumen of the small intestine in order to provide lubrication that can protect the epithelium and help with intestinal motility. The mechanism for fluid secretion is that solutes are first moved across the epithelium, which then draw water into the lumen by osmosis. The rate-limiting and regulated step in intestinal secretion is the movement of Cl– ions across the apical plasma membrane. The important proteins involved in secretion are diagrammed in the figure.

First, Cl– is transported into the epithelial cell by a cotransporter(the NKCC cotransporter) expressed on the basolateral membrane. As with the previous example, the Na+ gradient, established by the Na+/K+-ATPase, provides the energy to power transport of ions into the cell. The NKCC cotransporter moves one Na+, one K+, and 2 Cl– ions with each round of transport. Cl– flows down its concentration gradient into the lumen via the CFTR (green), a Cl– channel located on the apical plasma membrane. Not shown is that Na+ also flows into the lumen, by a passive mechanism.

Regulation of Secretion

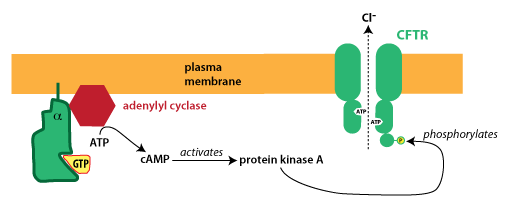

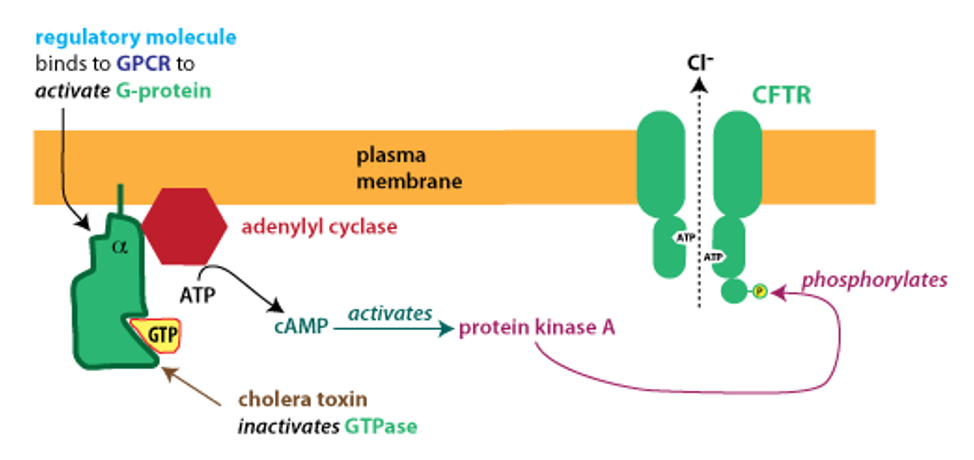

The CFTR protein is a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) protein family. CFTR is an atypical ABC protein; like other members of the ABC protein family, it binds ATP, but in this case ATP binding is used to open an ion channel. Importantly, the CFTR protein is also regulated by phophorylation: the protein has a regulatory domain that must be phosphorylated in order for the channel to open. The figure below depicts how secretion is turned on.

In the disorder cholera, a bacterial toxin blocks this signaling from turning off. The active G protein is normally inactivated after a short time because the alpha subunit acts as a GTPase, meaning it hydrolyzes GTP, converting it to GDP. (G proteins become active when they bind GTP and become inactive following GTP hydrolysis.)

Cholera toxin modifies the alpha subunit of the G protein, destroying its GTPase activity. The G protein remains in its activated state, causing continual production of cAMP, activation of PKA, and phosphorylation of CFTR. In patients with cholera, there is unregulated opening of CFTR, causing excessive, unregulated intestinal secretion. This results in watery diarrhea that can lead to dangerously severe dehydration.