2 Cancer Screening

Learning Objectives

- Discuss Risk factors for cancer.

- Discuss preventative measures to reduce risk of cancer.

- Discuss principles of screening for cancer.

- Review guidelines for common primary cancer screening modalities in the USA.

Introduction

Today we’ll focus on risk factors for cancer, ways we can work to prevent cancer, and methods of screening for cancer.

Cancer Risks and Prevention

Risk factors for cancer are broad and are varied. Some risk factors are modifiable, meaning that they can be mitigated/changed. Other risk factors are non-modifiable, meaning that they cannot be mitigated with interventions.

Certain infections increase risks for cancer. Hence, vaccinations, when they exist, to prevent infection can be a way of preventing cancer as well.

The following is a list of Infections associated with Cancer risk:

- HPV (Human Papilloma Virus): Cervical cancer, Anal cancer, Throat Cancer, Penile Cancer

- Hepatitis B: Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- Hepatitis C: Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- HTLV-1 (Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1): Adult T-cell leukemia

- HIV: Kaposi’s sarcoma and Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Human Herpes Virus 8 (HHV-8): Kaposi’s Sarcoma and primary effusion lymphoma

- EBV (Epstein-Barr Virus): Burkitt Lymphoma

- H. Pylori: Gastric Cancer and Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

- Liver Flukes: Cholangiocarcinoma and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Here are some ways we can mitigate Cancer Risk from Infections:

- HPV vaccination

- Hepatitis B vaccination

- Hepatitis C screening for infection, and treatment if one is infected may reduce long term risk of cancer (but the data is too early to tell, as we only recently have developed ways to treat hepatitis C infection).

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV infection.

- Treatment of HIV + patients with antiretroviral therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of AIDS-related lymphoma

- Prevention of STDs through barrier methods can be considered a form of cancer prevention in addition to preventing spread of infections.

- Needle-sharing programs that prevent infection spread could be considered a form of cancer prevention.

- Treatment of hepatitis B infection to reduce viral load can reduce risk of developing hepatoma (as well as liver damage/cirrhosis).

Tobacco use is by far the largest risk for cancer worldwide that can be mitigated. Tobacco is strongly associated with cancer in all forms: chewing, smoking, secondary smoke exposure, snuff use, and more. It is yet to be seen if vaping nicotine increases cancer risk. However, the aerosols from e-cigs do contain carcinogens, just in lower amounts than what is found in cigarette smoke.

Additional risk factors for Cancer include the following:

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Excess Body weight

- Alcohol consumption

- Sun and UV radiation exposure

- Air pollution

- Radon exposure (radon is frequently found in homes in Spokane, such that radon mitigation is now required in homes built in Spokane)

- Arsenic (can be found in drinking water)

- “Western” diet high in ultra-processed foods

- Genetic risks (Lynch syndrome, BRCA, and other inherited cancer syndromes)

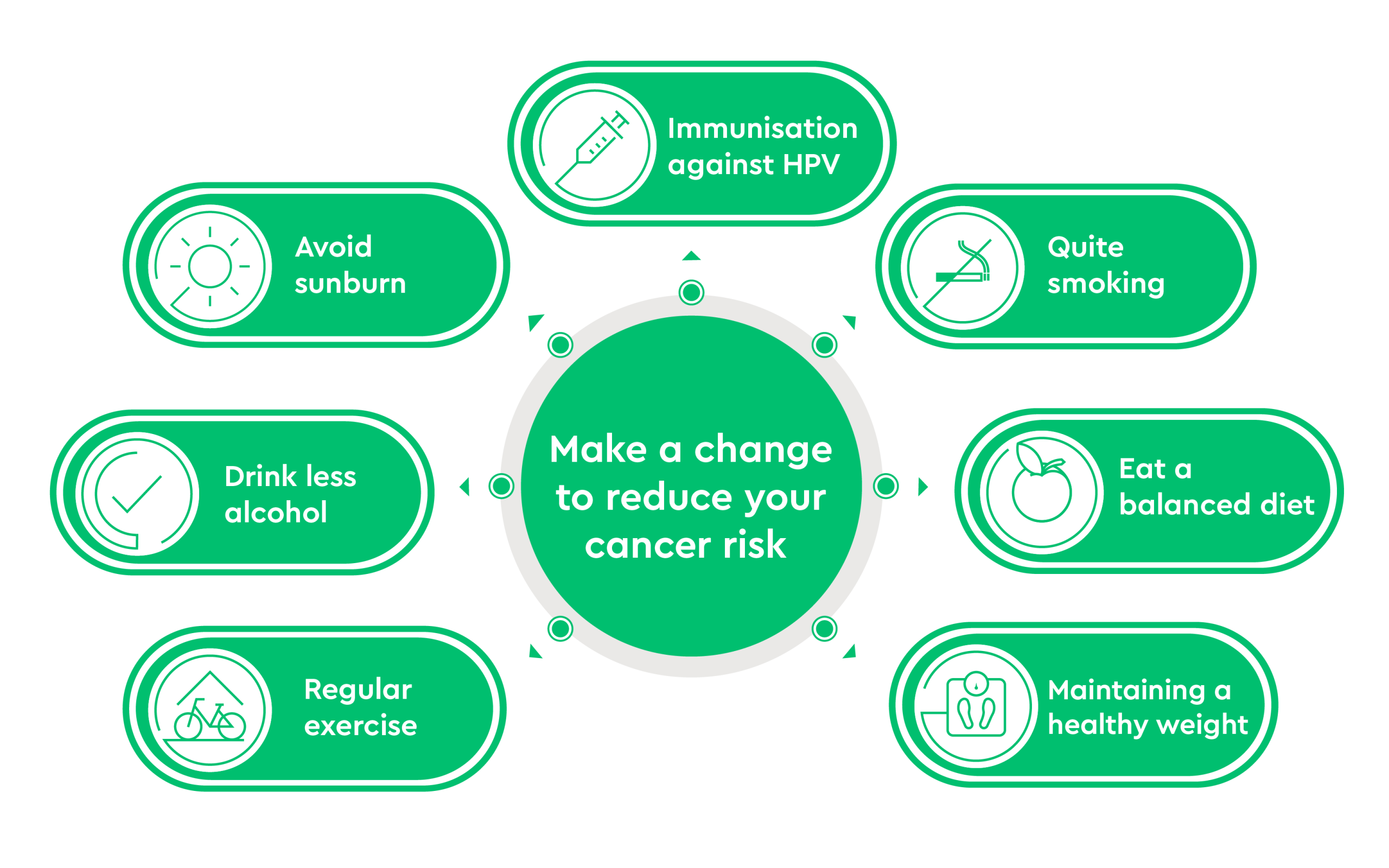

A lot of the above risk factors can be mitigated.

- Avoid/quit tobacco product use. Smoking cessation is key to cancer prevention.

- Increase physical activity (we don’t know how much activity to recommend, however).

- Weight loss: Is it modifiable?

- One could argue whether weight is a “modifiable” risk factor, as genetics and biology clearly play a role in body weight. Weight loss methods including bariatric surgery have been associated with decreased cancer mortality. It will be interesting to see if GLP-1 analogs, like Ozempic, are associated with lower cancer mortality in future studies.

- Avoid/minimize Alcohol use and treat alcohol use disorder.

- Minimize UV light exposure, avoid excessive sunlight exposure.

- Wear Sun-protective clothing. Use sunscreens with SPF rating of 30 or higher. Encourage use of sun protection especially in childhood and adolescence, when the majority of sun exposure generally occurs.

- Public policies to address air pollution

- Radon Testing and Mitigation (Spokane is known for being a high Radon area)

- Test municipal water regularly for Arsenic Content.

- Diet: 2020 American Cancer society recommends a healthy diet, defined as having a variety of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, and limiting or not including red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages, or highly processed foods and refined grain products.

Preventative care is important in preventing cancer, and this can be stressed with patients as we talk about preventative care to keep people healthy in general.

Immunizations: Prevent diseases that cause cancer.

Screening: Identification of asymptomatic cancer or risk factors for cancer (such as family history of cancer that might identify a genetic syndrome). Goal of screening is to identify problems early so that they can be fixed to improve health.

Behavioral counseling (lifestyle changes): Identify health behaviors that are detrimental to health (such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, etc.) and counsel patients about behaviors associated with poorer health outcomes.

Chemoprevention: Using drugs to prevent disease (such as aspirin use to reduce chance of stroke in a patient with a h/o transient ischemic attack). This has not hit prime time yet in oncology, but likely will change. Dietary changes may be a form of chemoprevention (eating a “healthier” diet).

Brief discussion of risk factors and tailoring cancer screening: As we discuss cancer screening, it is important to understand that screening for certain cancers is partly influenced by risk factors for cancers. We get better value for screening tests by screening those with known risk factors for cancers. This is why, for example, natal males who don’t take estrogen/progesterone are not screened for breast cancer. Risk factors can be modifiable, non-modifiable, genetic, viral, etc.

Examples of modifiable vs non-modifiable risk factors:

Modifiable Risk factor: An example is smoking (Quitting smoking can reduce risk of cancer.) We screen smokers and certain former smokers for lung cancer, but don’t screen non-smokers.

Non-modifiable risk factor: An example is natal gender, which influences recommendations about screening for breast and prostate cancer, as well as cervical cancer. (Aside: Obesity has been previously considered modifiable risk factor. With better understanding of weight and set points, obesity is likely to be considered as a non-modifiable/less modifiable risk factor for certain health concerns such as diabetes and liver disease. It remains to be seen if effective weight loss drugs such as Ozempic change excess weight back to a modifiable risk factor.)

Genetic Risk factor: An example of this is a person inheriting a BRCA gene mutation. Inheriting one of the Lynch syndrome genes. People who have inherited genes increasing their risks for cancer are screened differently than the general population. (You are not responsible for knowing how patients with inherited risks for cancer are screened.)

Viral Risk factor: HPV infection increases risks for head/neck, anal, penile, and cervical cancers. Patients with a h/o HPV infection should be evaluated for screening outside of standard screening.

Why we Screen for Cancer

Before discussing screening for different cancers below, we first need to discuss why we screen for cancer. In primary care, we screen for diabetes, iron deficiency in pregnancy, high cholesterol, and more. Why do this? The answer is because we can impact health outcomes for certain disorders and prevent more serious problems in patients who are found to have high cholesterol, iron deficiency in pregnancy, and diabetes. By diagnosing patients early with these problems, we can treat and prevent more serious outcomes that have significant health impacts.

In the setting of cancer, we screen for certain cancers because it has been found that diagnosis of these cancers in an earlier stage vastly improves cancer outcomes. Hence, it makes sense to screen populations at risk for certain cancers for those cancers to detect them early and thus improve outcomes.

Role of Screening in Preventative Medicine

Cancer screening is part of a broader care that we all do as physicians called preventative medicine. While we all went into medicine to cure patients of diseases, even better yet is preventing patients from getting disease in the first place. Per uptodate.com (an excellent resource, and you have access to this through the University of Washington library system), there are 4 main types of clinical preventative care: Immunizations, screening, behavioral counseling (aka lifestyle changes), and chemoprevention.

- Immunizations: Vaccines prevent diseases. In oncology, can you think of a vaccine that helps to prevent cancer? Answer: HPV vaccine! The Human Papilloma viruus (HPV) vaccine prevents infections with certain strains of HPV that are particularly prone to lead to cervical cancer, anal cancer, penile cancer, and throat cancer.

- Screening: Screening is the identification of asymptomatic diseases or risk factors. In the oncology arena, there are screening tests that have been shown to improve patient outcomes for breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, and cervical cancer. We will discuss screening for these cancers—how to do it/what is recommended. We will also discuss prostate cancer screening, which remains controversial as to its benefits vs harms. Cervical cancer screening is important and will be covered in your lifecycles class, so that isn’t discussed here. We will focus on general population screening recommendations. However, do realize that screening for cancer differs in populations with higher risks of certain cancers (think screening for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, screening differently for breast and ovarian cancer in patients with BRCA mutations, screening for renal cancer in patients on dialysis, etc). We won’t discuss high risk populations in this class, but as you specialize in medicine in your career, you will hear more about these topics….

- Behavioral counseling (lifestyle changes): Certain lifestyles/behaviors increase risks. Certain sexual practices increase risks for getting STDs, HIV, etc. Smoking is associated with a huge variety of health problems. Alcohol abuse is another behavior associated with several health concerns. Overeating and improper diets contribute to other health concerns. Physicians actively promote a healthy lifestyle as part of patient care and counsel patients about behaviors associated with poorer health outcomes.

- Chemoprevention: Note, this doesn’t refer to chemotherapy, but instead refers to use of drugs to prevent disease. For example, use of aspirin to reduce risk of stroke in certain populations, use of folate supplements to prevent neural tube defects in developing fetuses, and use of drugs to reduce cholesterol.

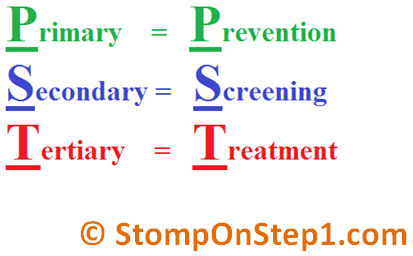

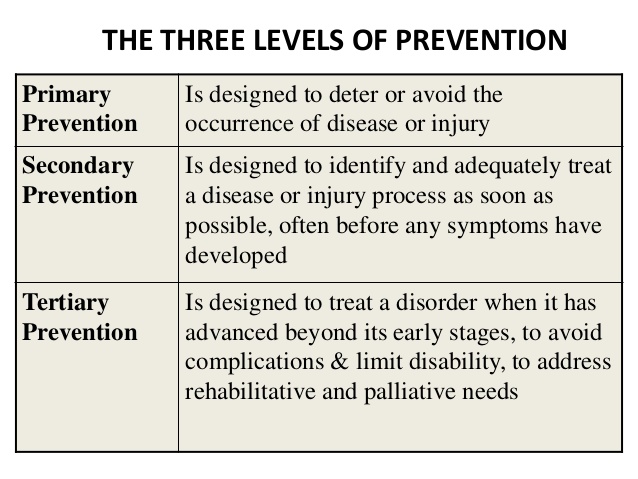

Primary vs Secondary vs Tertiary Prevention

With regards to the above clinical preventive care options, these can also be classified as Primary prevention, Secondary prevention, and Tertiary prevention.

- Primary prevention is a preventative care process that keeps a disease from occurring at all by removing the causes of disease in the first place.

- Secondary prevention detects early disease when it is asymptomatic and when treatment can stop it from progressing.

- Tertiary prevention describes clinical activities or treatments that prevent deterioration or reduce complications after a disease has declared itself. There can be some confusion in these concepts. For example, avoidance of alcohol by a person is a way of primary prevention against alcohol-induced diseases. However, in a patient who has developed cirrhosis in the setting of alcohol abuse, stopping alcohol consumption will help prevent/delay further deterioration of liver function.

In the cancer setting, HPV vaccine is an example of primary prevention of cancer—the HPV vaccine prevents infection with certain strains of HPV that can lead to cancer down the road.

Most cancer screening that we do and will discuss below is secondary prevention—the cancer has already occurred, but we are detecting it early before it has caused symptoms and hopefully before it has spread.

Principles of Screening: What makes a good screening test (review)

What makes a good screening test? When screening for a high-risk disease process such as cancer, we need to ensure we are using or designing screening tools that will achieve our goals. Below are factors that are important to assess in tools that are used for cancer screening.

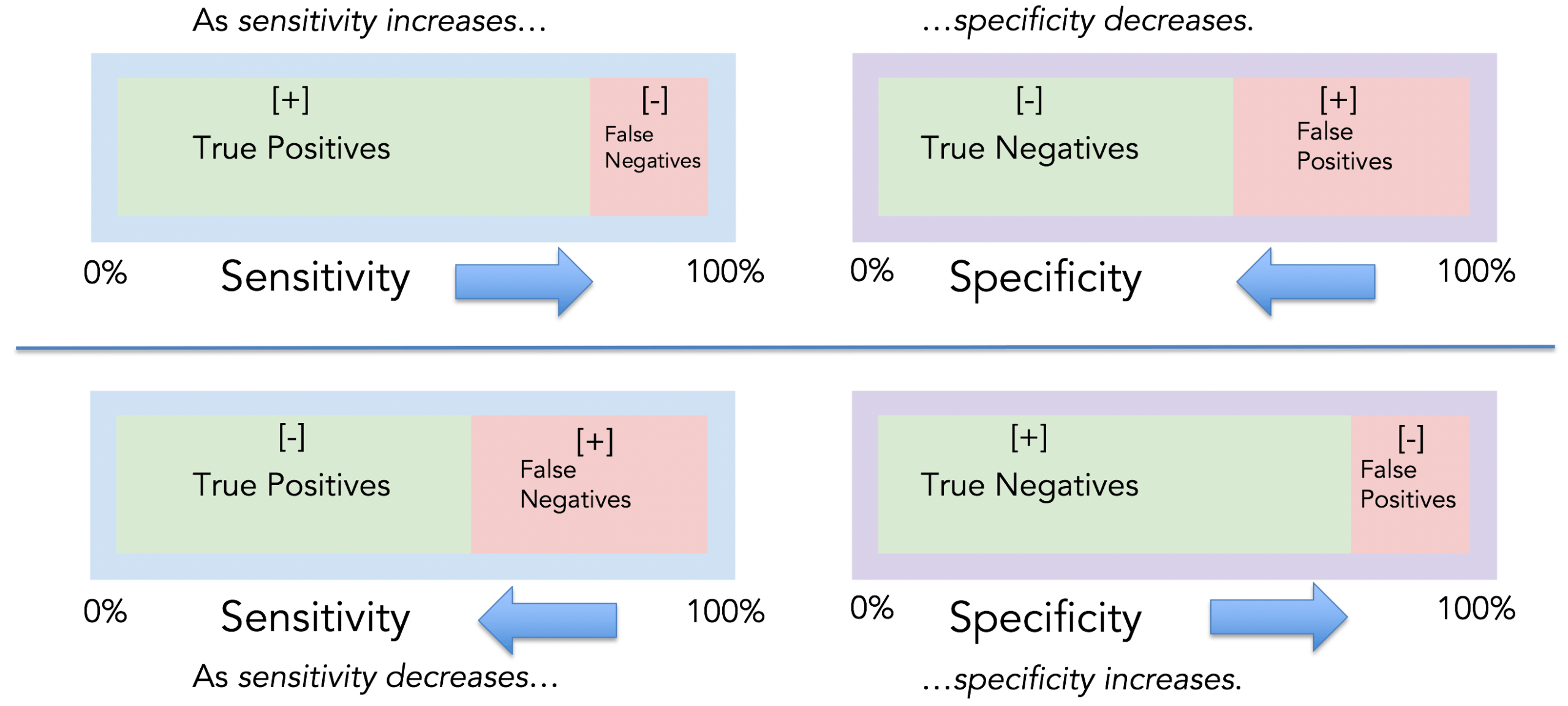

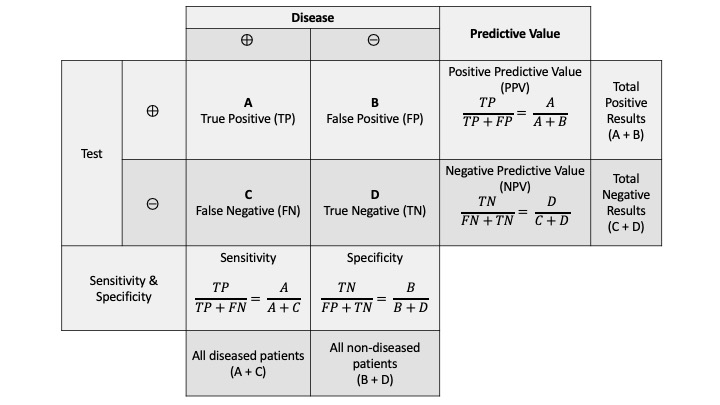

- High sensitivity and High specificity: In screening the general population for cancer (or other diseases), generally the prevalence of the specific problem that we are screening for is low in this general population. Hence, a good screening test much have a high sensitivity so that it does not miss the few cases of disease (cancer in this setting) present in the general population. This screening test also needs to be sensitive in early cancer. A screening test won’t be useful if it is sensitive for cancer only when that cancer has spread/metastasized. A screening test should also have a high specificity to reduce the number of people who have false positive tests from the screening. In cancer, particularly, a positive screening test will lead to additional procedures, often invasive, and we don’t want to be doing invasive procedures (with potential risks) on lots of people with false positive tests. For example, a PSA test for prostate cancer is easy to do but has significant issues with sensitivity and specificity. Also, it is not clear that PSA testing improves outcomes for patients ultimately diagnosed with prostate cancer.

- Acceptable Positive predictive value and Negative predictive value: Because of the low prevalence of diseases in asymptomatic people, the positive predictive value (true positives of all people who tests positive) of most screening tests is low, even for tests with high specificity. Hence, it is important to know and to educate patients that a positive screening test doesn’t guarantee they truly have a cancer, and a more invasive or costly test will be needed to confirm this. Conversely, in the general population, when a disease prevalence is low, the negative predictive value of a screening test (true negatives in a negative population), is high.

- Defined period of follow up: Follow up is important in cancer screening, since cancers often develop over time and patients with a negative screening test for cancer who are at risk for that cancer can develop it later. A challenge in cancer screening is to determine the correct period of follow up. If the follow up period is too short, disease missed by a screening test might not have a chance to make itself obvious on a subsequent screening test. If the follow up period in between screening tests is too long, then the first screening test may be deemed falsely insensitive, and the cancer diagnosed later than it should have been with subsequent testing/screening. There has been a lot of debate, for example, over the frequency at which we should be doing mammograms for breast cancer screening, and you’ll see that guidelines give a range of time interval for such repeat screening. Also, part of the defined period of follow up pertains to how long/often should we be screening certain populations to achieve the best benefit and cost effectiveness for screening for cancer.

- Simplicity and cost: The screening tests that are inexpensive and easy to do are more useful from a patient compliance standpoint. An ideal screening test should take only a few minutes to perform, require minimum preparation by the patient, depend on no special appointments, and be inexpensive. Unfortunately, most cancer screening tests tend to not meet these criteria. Breast cancer screening requires appointments for mammograms, which are expensive if one doesn’t have insurance. Colonoscopy, a fantastic way to screen for colon cancer, requires a special diet for a few days, followed by a bowel clean out that takes a few hours, and then the actual colonoscopy—which must be scheduled in advance and is expensive. Lung cancer screening that has been clinically shown to be effective requires a CT scan of the chest—again requiring scheduling in advance and it is costly.

- Safety: A screening test should be safe overall. Particularly in cancer screening, it is important to weigh safety of the test against cancer risk when recommending a cancer screening test. For example, if the colon perforation rate of colonoscopy is 1/1000, when colonoscopy is used to screen for colon cancer in people in their 50s, the risk of perforation would be higher than the chance of colon cancer. (Per Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the risk of perforation in patients younger than 75 is 0.007%, and the risk in patients 75 and older is 0.3%.)

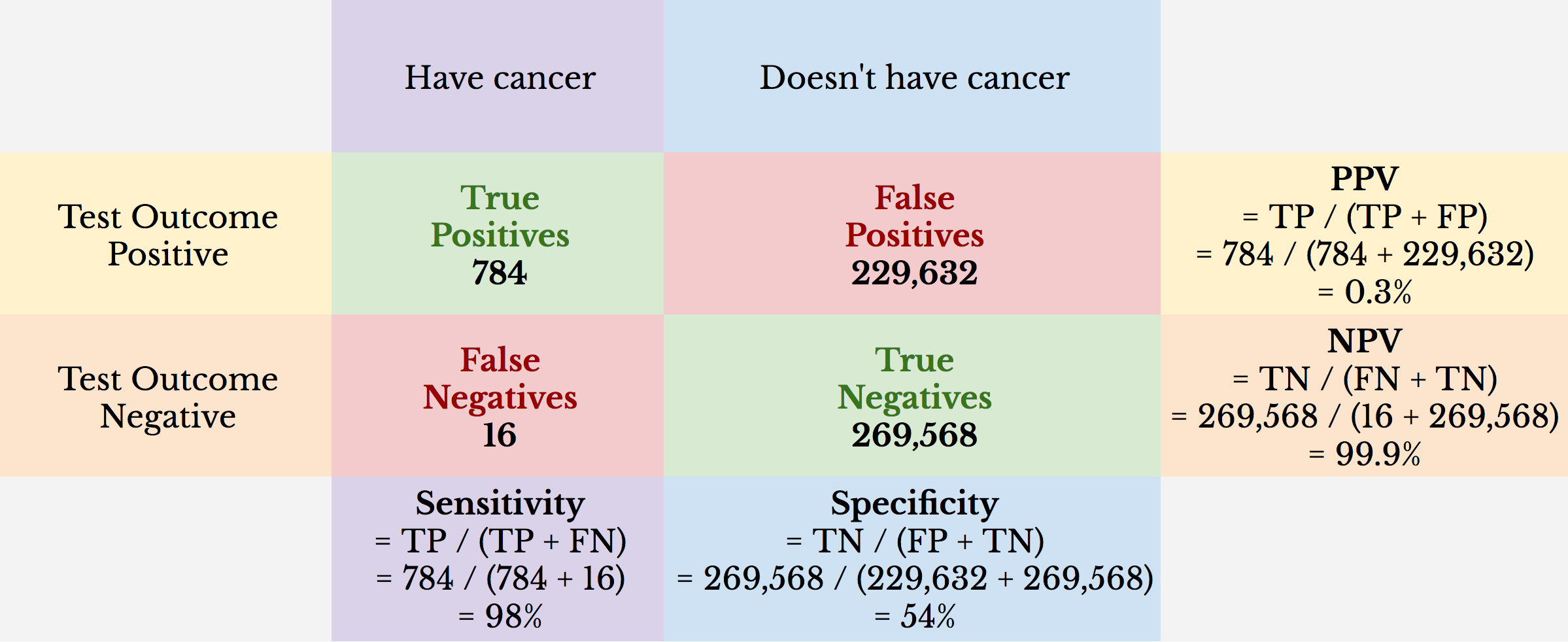

The following images may be helpful for a reminder about sensitivity, specificity, Positive Predictive value, negative predictive value, and an example of such findings with a genetic cancer screening test:

The above example demonstrates a cancer screening test with high sensitivity but low specificity. This results in an unacceptable false positive rate such that the positive predictive value of the cancer screening test is quite low.

Unintended Consequences of Screening

It is important to be aware of unintended consequences of screening and to preemptively address these with patients when ordering screening tests:

- Risk of false-positive tests: Patients who have a positive screening test for cancer will experience anxiety, and a false positive test will also lead to further testing that can be invasive. The more frequently a screening test is done, the more likely a given patient will experience a false positive test. For example, if a mammogram for breast cancer gives false-positive results 7-12 % of the time, then a woman who has 30 mammograms in her lifetime is likely going to have at least one false-positive test.

- Risk of negative labelling effect: Patients with a screening test that comes back positive for a problem get labelled as having a problem until that test is proven to be false. Patients with a false-positive test who have previously been healthy may think of themselves as less healthy or more vulnerable to disease.

- Risk of overdiagnosis: Screening can detect cancers that might not have led to morbidity or mortality in undetected. This is particularly true in older patients with co-morbidities and in the setting of PSA screening (more on this below). Screening will detect cancers earlier than they would have manifested, and it is common to see a temporary increase in the incidence of cancer in a population when a screening test is first implemented, as we are essentially moving the time of diagnosis earlier in a person’s life and catching more cancers at a point in time until the screening test has been implemented for a long time.

- Risk of Incidentalomas: Using CT for screening tests has become more common. Unlike most screening tests, CT often visualizes much more than a targeted area of interest. Hence, CT scans commonly pick up tiny lung nodules, pancreas lesions that aren’t cancer, etc.

Putting it all together

Putting this all together: Screening is important. However, like all of medicine, there are cons as well as pros. General screening recommendations apply to the general population, but it is important that patients understand (as well as doctors) the meanings/pros/cons of the various tests. It is important when discussing preventative care/cancer screening, that the benefits of screening as well as its harms are discussed and weighed for each individual patient as the tests are ordered.

Cancer Screening Guidelines by Disease Type

We’ll now move on to discuss Cancer screening in Breast cancer, Prostate Cancer, Colon cancer, and Lung cancer. As previously discussed, Cervical cancer screening/HPV screening will be discussed in lifecycles but do be aware that this is an important screening tool as well and has dramatically reduced the incidence of invasive cervical cancer in societies that perform this screening. Note that all guidelines discussed are based upon United States guidelines. Guidelines do vary some by country.

Gender definitions

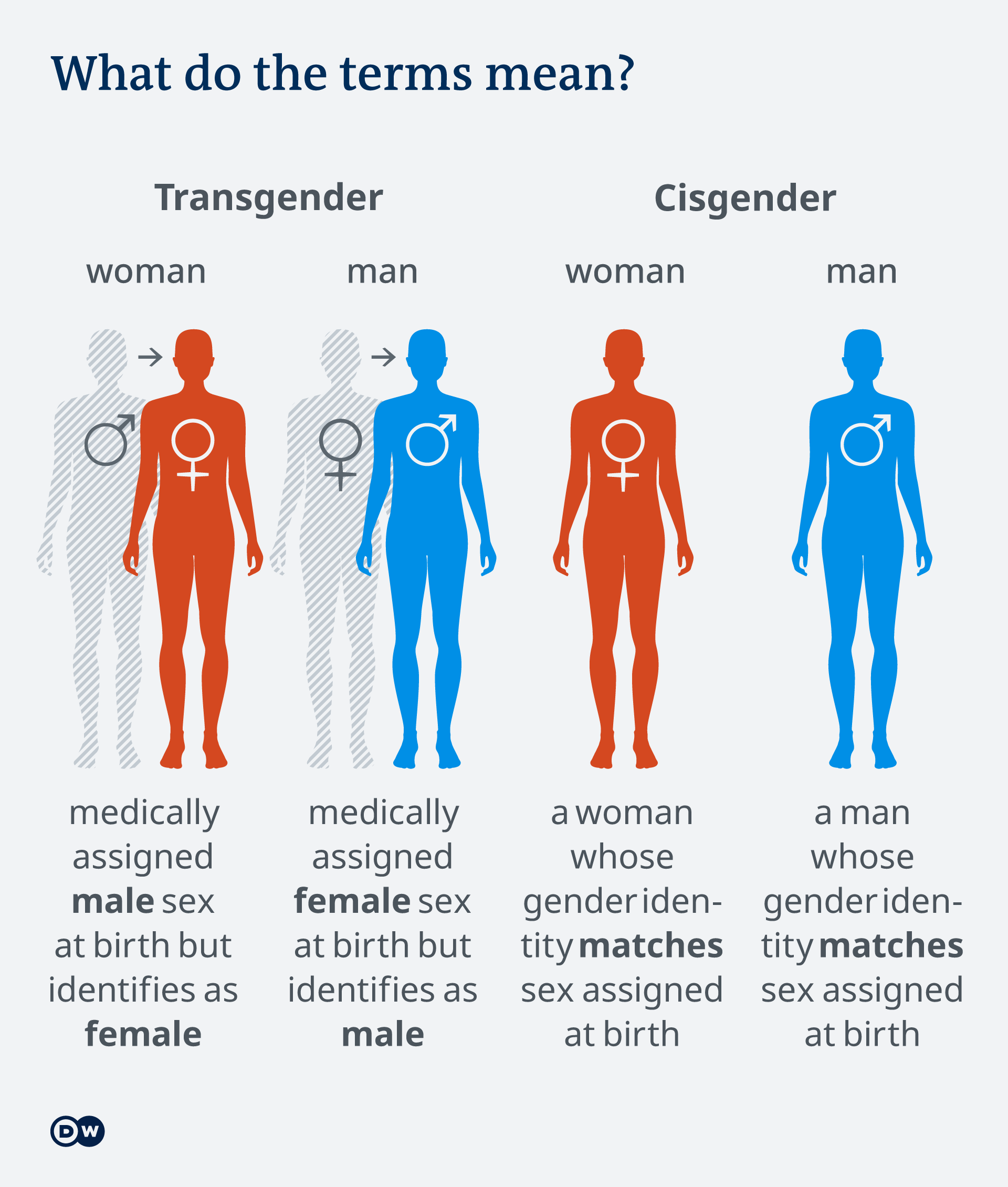

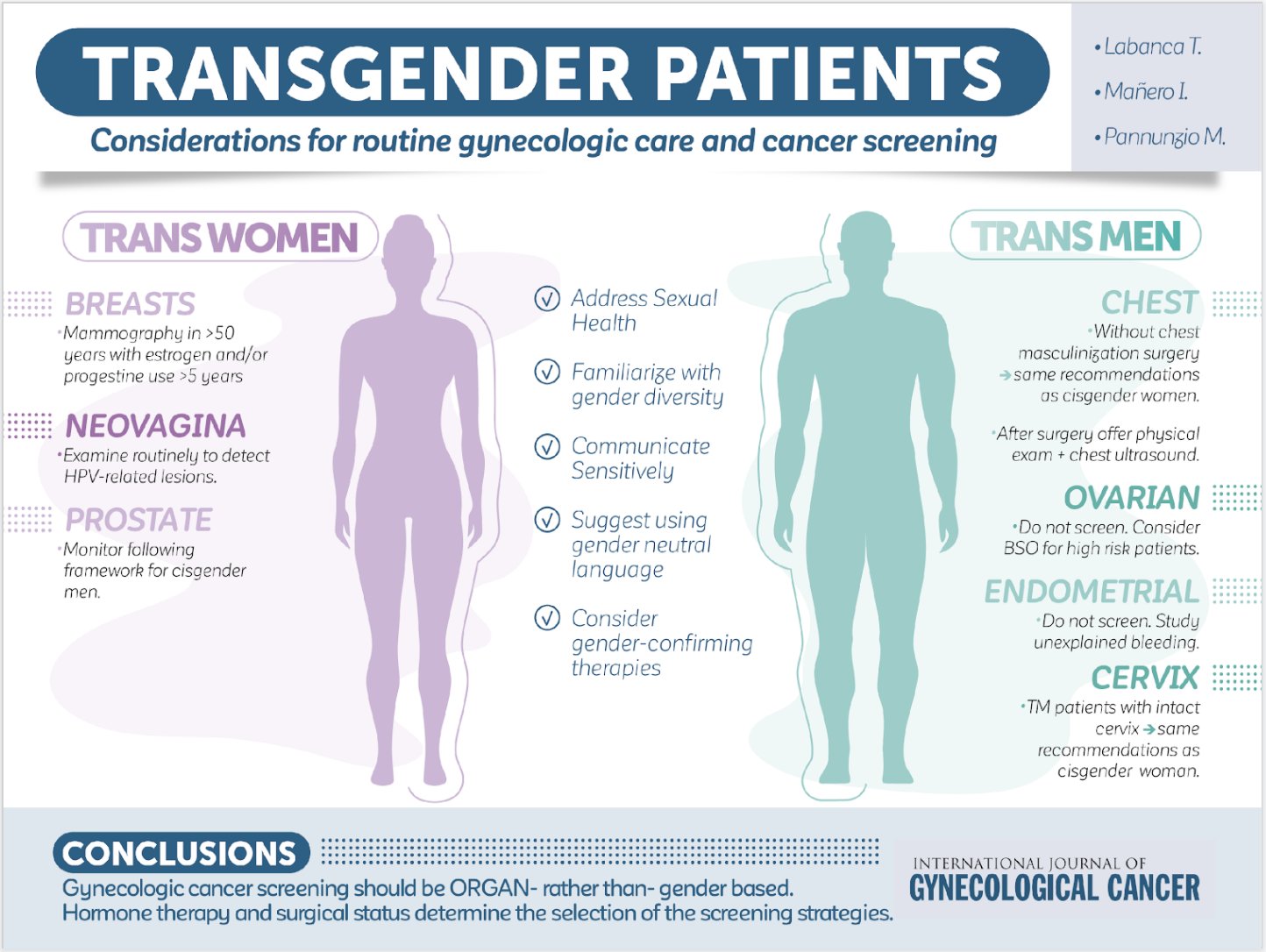

In the following discussion, please be aware that screening for certain cancers varies by gender. We will be using the term cisgender women to refer to people whose chromosomes are XX (natal gender is female) and cisgender men to people whose chromosomes are XY (natal gender is male). (In the setting of people who are XY but have a mutation in their testosterone receptor such that they manifest as female in body characteristics, they are also screened for cancer as XX individuals—you’ll learn more on this in lifecycles class next year). Transgender woman defines a woman who was medically assigned male sex (chromosomes XY) at birth but identifies as female. Transgender man defines a man who was medically assigned female sex (chromosomes XX) at birth but identifies as male. In the setting of transgender medicine, it is important to know that cancer screening will vary in patients who transition from one gender to another. For example, transgender women often will take hormones that increase risks for breast cancer, and so one would generally screen for breast cancer in transgender women. Transgender women, however, still have a prostate, and screening for prostate cancer needs to be discussed with them. Transgender men who still have intact breasts should continue to undergo mammogram for breast cancer screening. Transgender men who have a cervix will need cervical cancer screening.

Breast Cancer Screening (in Average Risk populations)

Women in the general population have an average risk for breast cancer (less than 15% lifetime risk of breast cancer). However, the risk of breast cancer varies depending upon age. Incidence of breast cancer is quite low under the age of 40 and then begins to rise as women age. Men in the general population are at an extremely low risk of developing breast cancer and do not require breast cancer screening. Sensitivity and specificity of mammogram, which is the screening test that is least expensive and with the most data about use, is age-dependent in women. Sensitivity and specificity of mammogram are higher in older women and lower in younger women. Hence, the benefit of breast cancer screening is low in very young women, and the increases with the age of women. Recommendations for breast cancer screening in women in the general population based upon age.

Cisgender men of any age: No breast cancer screening recommended due to the extremely low incidence of breast cancer in natal men.

Cisgender women under age 40: Incidence of breast cancer is low in women under 40. There are no randomized trials of breast cancer screening done in this patient population. Thus, no screening guidelines recommend routine screening for average-risk women under the age of 40. In this patient population the tradeoffs between risks of testing (false positive mammogram, anxiety, etc) generally outweigh the tiny chance that the patient actually has breast cancer.

Cisgender women ages 40-49: In the USA, we generally have shared decision making with women aged 40-49 about breast cancer screening. There are tradeoffs between benefits and harms, although studies in the USA do show a small benefit to breast cancer screening in this age group. Decisions on screening in this age group often depend on a patient’s values and preferences. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nine randomized trials showed a trend suggesting that for 10,000 women screened over 10 years, 3 deaths from breast cancer could be prevented. One additional potential benefit for screening women ages 40-49 is to get them in a mindset of getting screening done, getting baseline mammograms (mammograms to serve as baseline comparisons to when they have future mammograms done at an older age), and getting them used to the mammographic screening. In women ages 40-49, if they wish to do screening, we generally suggest this be done every 1 to 2 years.

Cisgender women ages 50-74: There is good data (see lecture slides) that breast cancer screening decreases breast cancer mortality in this age group. Also, screening reduced the risk of advanced breast cancer, presumably because cancers were diagnosed earlier with screening. Breast cancer that is caught early is much more likely to be cured by surgery alone, and such patients may not need chemotherapy/adjuvant therapy after surgery to improve their odds of cure. We typically screen patients every year. Technically, screening women in this age group is acceptable to be 1-2 years. However, in practice, patients who opt to get screened only every 2 years often end up going longer in between screenings than 2 years, so we prefer to try to do yearly screening in this population.

Cisgender women ages 75 and over: There is no defined upper age limit to screening for breast cancer. As women age, their incidence of breast cancer continues to rise and remains high into their 80s. However, as women age, their number of remaining years of life decreased due to expected mortality of aging. Hence, as women age, the number of life-years saved by screening for breast cancer goes down. Shared decision making should be made with women ages 75 and older about breast cancer screening. We generally recommend that women ages 75 and older continue breast cancer screening if their life-expectancy is estimated to be at least 10 years. We consider stopping breast cancer screening for a woman if her life expectancy is under 10 years. This is partly because the potential harms of screening occur mostly immediately with the screening test, while the benefits of screening may occur later in life.

Transgender women: Discuss and recommend screening in patients ages 50 or older who have additional risk factors for breast cancer, which include estrogen/progestin therapy for >5 years, family h/o breast cancer, body mass index (BMI) >35.

Transgender men: Those with intact breasts should have the same screening as would be done for natal females. For transgender men who have undergone mastectomy, a yearly chest wall exam and axillary node exam is suggested by some authors as a pretext for discussing with patients that they still have a small risk for breast cancer in any remaining breast tissue in the chest wall or breast cancer in the nodes of the axillae, although the risk is quite low.

Breast Cancer Screening Modalities

Mammography (mammogram): This is the best studied imaging technique used to screen for breast cancer. It involves imaging breasts with x-rays. The woman’s breast is compressed flat for the imaging, and generally 2 varying views of each breast are obtained. Imaging technicians work to ensure that axillary tissues with nodes are included in the mammographic views. Mammography is the only technique that has been shown to decrease breast cancer mortality in multiple clinical trials.

Breast Ultrasound: Ultrasounds of breast tissue have not been evaluated as a screening modality for breast cancer. However, Breast Ultrasound is used as part of an evaluation of a breast mass that is either found by clinical exam (palpable breast lump) or part of follow up imaging of a questionable finding on routine mammogram.

Breast MRI: Breast MRI is not recommended as a screening tool for average-risk women for breast cancer. It is performed in combination with mammogram and is sued to screening high risk patients such as women with BRCA mutations. Breast MRI has a higher sensitivity than mammogram in detecting invasive breast cancer BUT has a lower sensitivity at detecting ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast MRI requires administration of IV contrast. Breast MRI is much more expensive than mammogram.

Past breast cancer screening techniques that are no longer recommended:

- Clinical breast exam by health care provider: this is not useful for screening in an asymptomatic patient. However, this should be done if a patient presents with a breast complaint.

- Breast self-examination (BSE) by the patient: Data shows this doesn’t prevent breast cancer/lead to early detection. Instead, this leads to a higher rate of breast biopsy that shows benign disease.

Benefits and Harms of Breast cancer Screening

Benefits of Breast cancer screening:

In concrete terms, general population patients can be advised that breast cancer screening clearly reduces breast cancer mortality. In addition, screening mammograms reduce the odds of dying of breast cancer by about 20%. It is important to note, however, that risk reduction of breast cancer mortality with screening does vary by age of the patient and somewhat by breast density. Overall, the benefits of breast cancer screening, given the significant mortality benefit, are thought to outweigh risks/harms.

Harms of Breast cancer screening:

As with all areas of medicine, there are risks as well as benefits to breast cancer screening.

- The main risk is over-diagnosis. Over-diagnosis of breast cancer occurs when screening leads to identification of a breast cancer that would not have caused clinical consequences in a woman’s lifetime had it not been detected. Hence, we tend to not recommend breast cancer screening in a woman with a limited life expectancy, such that a diagnosis of breast cancer, if untreated, would be unlikely to impact her life. For example, a woman with metastatic lung cancer can safely forego breast cancer screening, as she is likely to die of lung cancer in the next 5 years. A woman in her 90s who is unlikely to reach 100 generally can forgo breast cancer screening to avoid overdiagnosis that might lead to procedures that reduce her quality of remaining life.)

- Another problem or potential harm is false-positive mammogram results. In the USA, about 10% of screening mammograms are false positives. After about 10 years of annual screening, about 50% of women have experienced a false positive result. False positive findings will lead to biopsies/other procedures, which are invasive. Concerning findings on a mammogram lead to patient anxiety. This can be lessened some by educating patients about the chances of false positive findings/preparing patients for the possibility of false positive findings.

- False-negative mammogram results are a risk to patients. False-negative results are due to either a radiologist error (missed the cancer finding) or due to the cancer not being mammographically visible on the imaging, even in retrospective review. Dense breasts are at more risk for false negative findings on mammogram, as cancers can be hidden by the dense breast tissue. Obviously, the harm in this situation is delay in a diagnosis, leading to the cancer being diagnosed at a later date/possibly when it is more invasive.

- Radiation exposure from getting a mammogram: Although radiation can increase the risk of breast cancer, radiation from a screening mammogram is low enough that, for average-risk women over age 40, the benefits of screening outweigh the risk of radiation from mammography.

- Discomfort from getting a mammogram is generally mild and transient—only experienced during the breast compression for the mammogram, which is generally a few minutes at most. However, some patients find mammograms more painful than others. Patient education and advise about pain management can mitigate this.

Barriers/Disparities in Breast Cancer Screening

There are ongoing areas of improvement needed with regards to barriers that impair a patient’s ability to get a mammogram. Lack of insurance is a primary driver. Although patients don’t need a primary care provider to get a mammogram, many don’t know how to do this without their primary care doctor ordering one, so lack of having a primary care doctor is a barrier. Patients often don’t know screening recommendations for cancer and don’t know how to scheduler a mammogram on their own. Also, the fact that a mammogram needs to be scheduled (you can’t just walk in and get one done) is another barrier. Other barriers include lack of quality mammogram equipment in rural centers, lack of transportation to get a mammogram, need to take time off from work for a mammogram, need for childcare for Mom’s to go get a mammogram, and other socioeconomic factors. All of the above tie into racial disparities in breast cancer screening.

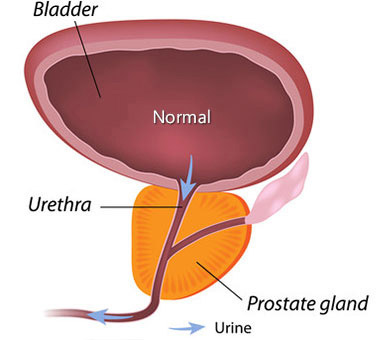

Prostate Cancer screening

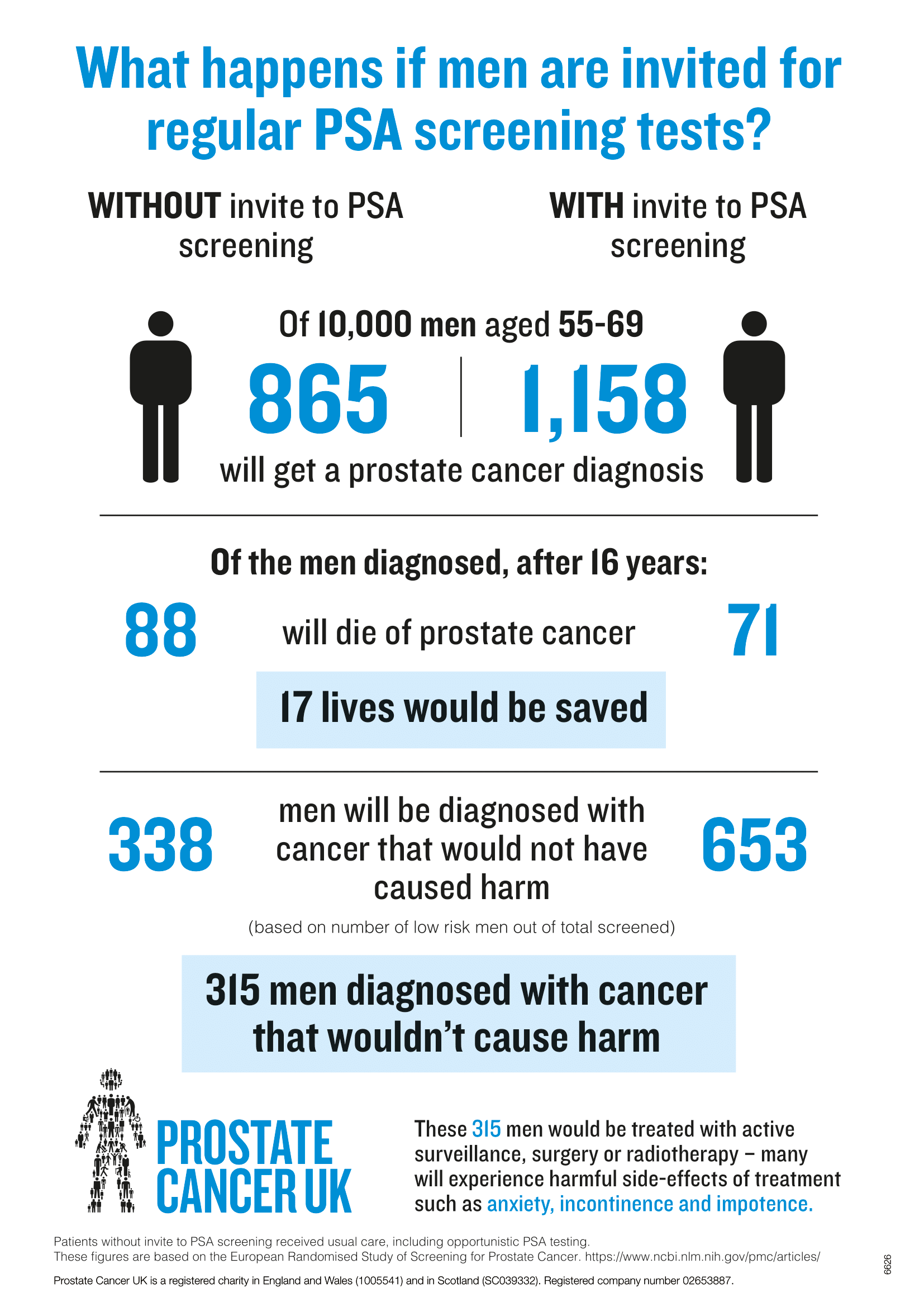

Prostate cancer is quite common. However, in many cases prostate cancer grows so slowly that it doesn’t impact a person’s survival. Thus, routine screening for prostate cancer is controversial. We’ll review the data and discuss shared decision making.

Without screening, many cases of prostate cancer do not ever become clinically evident. Data suggests that prostate cancer often grows so slowly that most men die of other causes before their prostate cancer becomes clinically advanced. At autopsy of men who died of other causes, prostate cancer detection rates as follows:

- 30% for men in their fifties

- Up to 70% for men in their 70s.

These findings are higher than the lifetime incidence of diagnosed prostate cancer in male populations.

However, prostate cancer mortality rates in the USA did decline between 1992 and 2017. Simulation models have suggested that PSA (prostate-specific antigen) screening could account for 45 to 70% of this decline.

Benefits of Prostate Cancer Screening

Screening for prostate cancer does increase the detection of prostate cancer in men and may reduce the risk for distant-stage prostate cancer. However, studies are problematic, and there are problems with bias in these studies. At most, PSA screening has a small benefit in reducing prostate cancer mortality. However, PSA screening has no benefit in reducing overall mortality in people with prostates.

Harms of Prostate Cancer Screening

The PSA test is a blood draw. There are mild risks of bleeding/infection/pain from a blood draw. However, if a PSA result is concerning, this will necessitate further work up, including a prostate biopsy. There are risks to a prostate biopsy, including infection, pain, bleeding, and urinary obstruction. These complications of prostate biopsy occur in up to 2% of men who have a prostate biopsy. Also, prostate cancer screening with PSA does lead to overdiagnosis of prostate cancer. Again, overdiagnosis refers to the detection by screening of a condition that would not have become clinically significant in the patient’s lifetime. This is a real concern with PSA screening, given that up to 70% of men 70 and older who died of causes OTHER than prostate cancer are found to have prostate cancer at autopsy. Other harms from prostate cancer screening include false-positive PSA, Anxiety, and a biopsy done after a high PSA that comes back as a falsely negative biopsy. Lastly, screening that finds prostate cancer can lead to interventions including surgery and/or radiation therapy (XRT). There is an operative mortality risk from prostate cancer surgery. Treatments for prostate cancer (XRT or surgery) cause urinary symptoms and can lead to impotence, urinary incontinence, and bowel dysfunction.

Overdiagnosis of Prostate cancer

The potential for overdiagnosis of prostate cancer appears to be substantial with PSA screening, given the high prevalence of undiagnosed prostate cancer detected on autopsy series. Overdiagnosis is of particular concern because most men with screening-detected prostate cancers have early-stage disease and may be offered aggressive therapies (prostatectomy or stereotactic radiation) that may produce long-lasting adverse effects (impotence, urinary incontinence). However, the increased use of active surveillance to manage diagnosed prostate cancer, rather than aggressive treatment, may help to mitigate the treatment-related harms of overdiagnosis of prostate cancer.

Approach to Prostate Cancer Screening

Unlikely breast cancer, colon cancer, and lung cancer screening–where data is clear as to benefits, the benefits to prostate cancer screening are less clear cut. Hence, when one discusses prostate cancer screening with patients, one uses a model of shared decision-making. Shared decision-making is a process where a patient and their doctor are involved together to make a decision about health care for the patient. In the setting of deciding to screen for prostate cancer, shared decision making is key as the prevalence of prostate cancer is high, but the impact of screening is very low. Also, in the setting where screening leads to procedures, there are notable risks to these procedures, which factor in when one accounts for the impact of screening having a low impact on overall mortality.

Key points in shared decision-making pertaining to prostate cancer when you have these conversations with patients:

- Prostate cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers and a leading cause of cancer death in men.

- Prostate cancer screening may reduce the chance of dying from prostate cancer, but the absolute benefit is small. Most men who choose not to be screened with a PSA test will not be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime and will die from some other cause.

- If screening is done, a PSA is checked every 1 to 2 years. The PSA test is not a test specifically for cancer. It can be abnormal even if there is no prostate cancer. Also, it may be normal even if there is a prostate cancer.

- A prostate biopsy is needed to determine whether prostate cancer is present. Hence, an abnormal PSA will lead to a recommendation for a prostate biopsy.

- Patients who choose to be screened with a PSA test are much more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer than those who decline PSA screening.

- No available tests can accurately determine which men with a prostate cancer found by screening have a cancer that is destined to cause health problems and, hence, would benefit from aggressive treatment.

- Surgery and radiation therapies are the treatments most commonly offered to try to cure prostate cancer. These treatments have risks of urinary incontinence, impotence, and bowel problems.

A Risk-adjusted approach for Prostate Cancer Screening Discussion with Patients

- For average risk cisgender men: We suggest a discussion of prostate cancer screening at age 50, as long as life expectancy is at least 10 years.

- BRCA Carriers: Cisgender men and transgender women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations have a higher risk for prostate cancer. Hence it is suggested that a discussion with them about prostate cancer screening beginning as early as age 40 occur, although data on effectiveness of screening for prostate cancer in this population remains limited.

- Black Cisgender Men: Black men have a higher risk for prostate cancer, and a discussion regarding prostate cancer screening is warranted between age 40 and 45 (as opposed to waiting until age 50).

- Cisgender Men with a family history of prostate cancer: Men with a family history of prostate cancer, particularly those who have a first degree relative who was diagnosed with prostate cancer prior to age 65 should have a discussion re: prostate cancer screening at age 45-50.

- Transgender women: Routine screening should be discussed with shared decision making as would be done for cisgender men above.

Note: Cisgender men and transgender women at higher risk of prostate cancer may be more likely to benefit from screening. However, there is a paucity of studies addressing such screening in higher risk men. Hence, these people should be informed that the potential benefits and risks of earlier screening remain uncertain.

What does Prostate Cancer Screening Entail?

Generally, the screening test done for prostate cancer screening is a PSA, a blood test. If screening is desired by the patient, this is the test to do. It is important to note that PSA varies naturally by age.

Note, the PSA is higher with older age in healthy males.

Ranges of PSA based upon age (you don’t need to memorize this, but should be aware PSA varies with age):

40-49: 0 to 2.5 ng/mL

50-59: 0 to 3.5 ng/mL

60-69: 0 to 4.5 ng/mL

70-79: 0 to 6.5 ng/mL

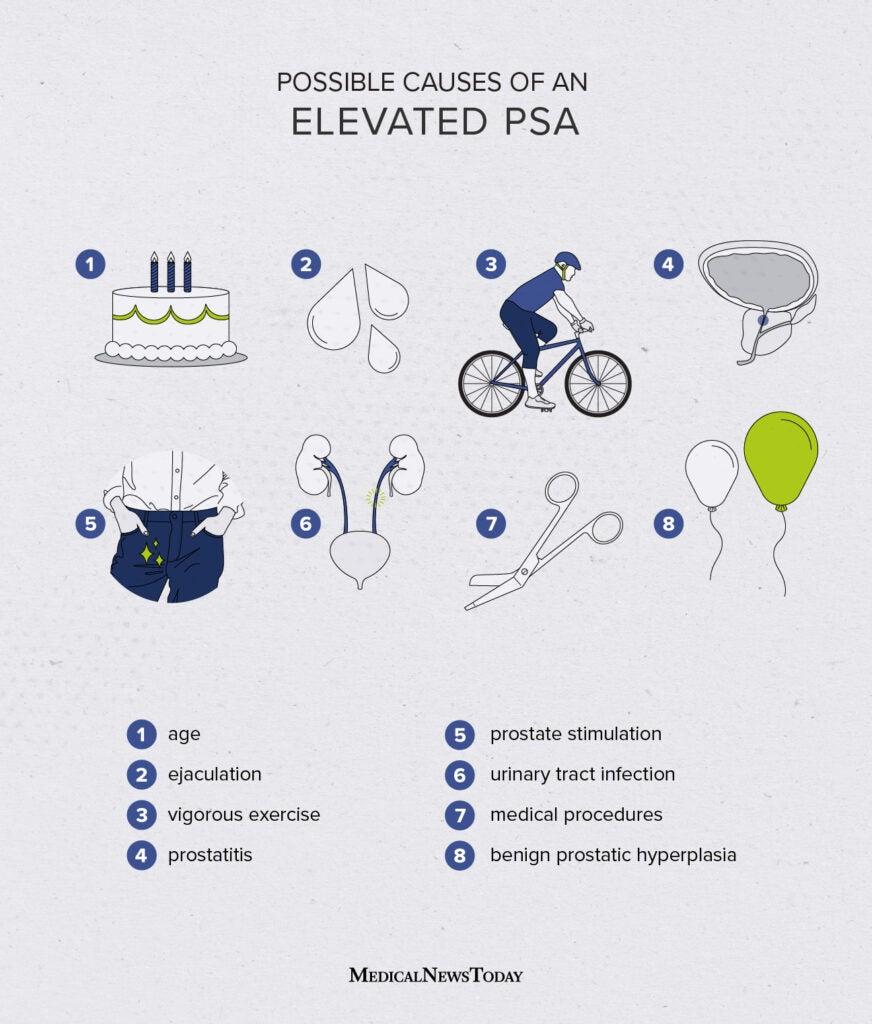

Studies estimate that PSA elevations may precede clinical manifestations of prostate cancer by 5 to 10 or more years. However, it is important to know that the PSA is not specific to prostate cancer. The PSA can be elevated in the following conditions:

- Prostate cancer

- Benign Prostate Hyperplasia

- Prostatitis

- Subclinical prostatic inflammation

- Prostate biopsy

- Cystoscopy

- TURP (transurethral prostatic resection—used to treat BPH)

- Urinary Retention

- Ejaculation

- Perineal trauma

- Prostatic Infarction

It is generally recommended that PSA testing be deferred for at least 2 weeks after treatment for acute urinary retention or for at least 2 weeks after urethral instrumentation (such as placement of a foley catheter).

It is also important to know that 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (such as finasteride or dutasteride, which are used to treat Prostate hyperplasia) lower PSA results. Hence, the PSA result needs to be “corrected” if a patient is taking this type of medication.

Digital Rectal Exam (DRE): In the past, DRE was a common part of the physical exam, where the prostate can be palpated. However, DRE is not generally used now as a screening test for prostate cancer.

Prostate Cancer Screening done and abnormal findings: When to refer to Urology?

- PSA greater than or equal to 4 ng/mL: Patients with this PSA result are referred to urology for a prostate biopsy. (In some places, if the PSA is 4-7, it is repeated 6 to 8 weeks later before urology referral, as the PSA may be transiently elevated due to other conditions, as we have outlined above.)

- A rise in PSA while on 5-alpha reductase inhibitor: A patient taking finasteride or detasteride for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) with a confirmed PSA level risk of 0.5 ng/mL over ANY time frame should be referred to urology for prostate biopsy.

- Abnormal prostate exam (DRE): Although DRE is not generally used for screening (since most of the prostate is not palpated during DRE), if a symptom warrants an exam and the exam of the prostate is abnormal with a finding of nodules, induration, or asymmetry, then referral to urology is warranted. Symmetric enlargement and firmness of the prostate are frequent in men with BPH and don’t typically warrant urology referral.

Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Screening

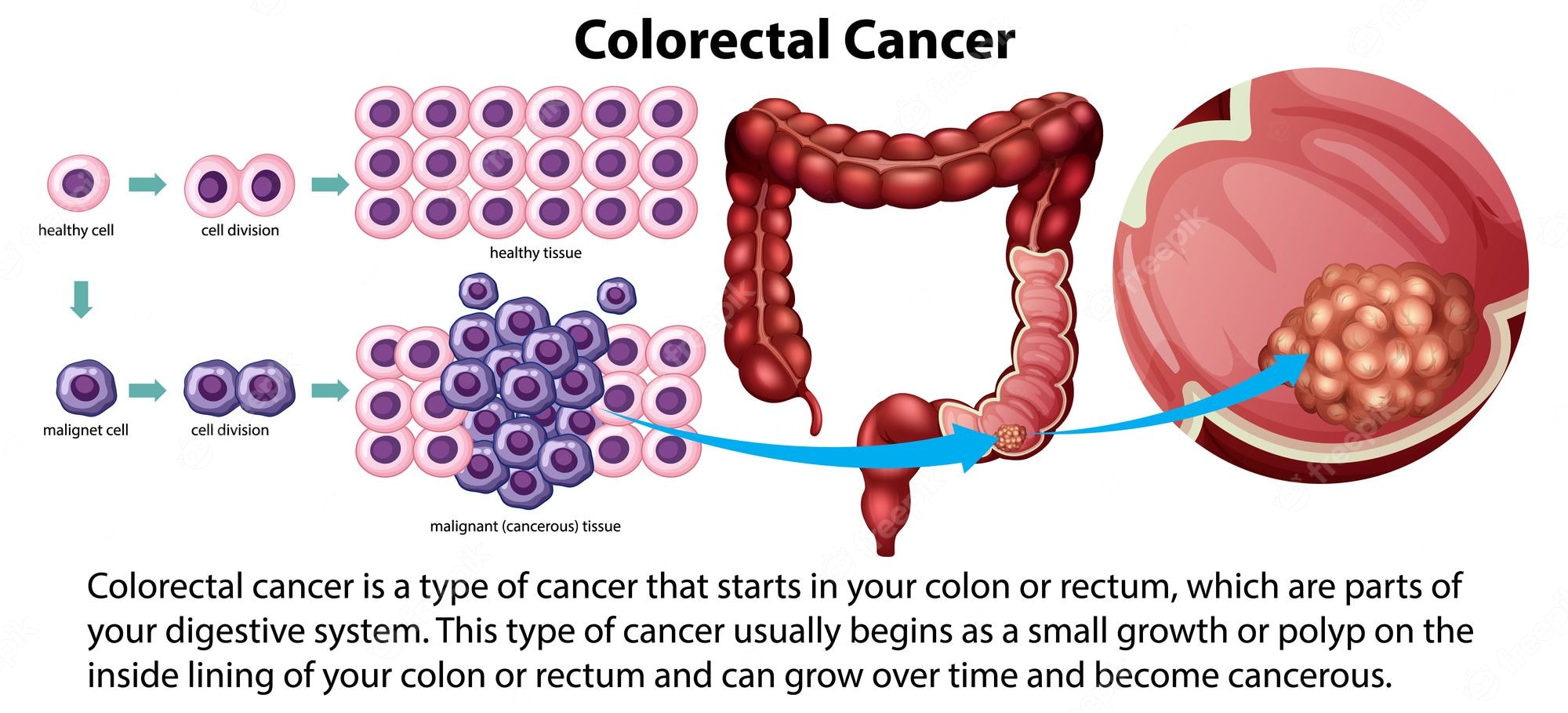

When we talk about colon cancer or colorectal cancer screening, we are referring to cancers of the large intestine, which includes both the colon and the rectum. We often shorten “colorectal” to “colon” when we discuss screening. However, colon cancer screening includes screening the rectum, so the proper term would be colorectal cancer screening (but you’ll hear us say colon cancer screening all the time—part of our doctor lingo). I’ll try to stick to the more correct terminology in this course pack material, but forgive me if I relapse to shortened lingo!

Most colorectal cancers arise from adenomatous polyps in the colon. Adenomatous polyps are found in about 30% of men and 20% of women. Benign adenomas can transition to carcinomas, and the progression from adenoma to carcinoma is believed to average about 10 years. Interestingly, the incidence and mortality rates of colon cancer in the USA have been declining. This decline is thought to be partly due to screening—during colonoscopy screening polyps are removed at the time of colonoscopy. It is thought this removal of adenomatous polyps decreases the likelihood that they’ll grow into cancerous polyps over the ensuing 10 years (which would potentially occur if they were left in place).

More recently there has been an uptick in colon cancer in younger ages. Cause for this is not completely clear, but it is thought to be related to our high fat/lower fiber diet in Western Countries. Hence, recently the age recommended for first colonoscopy/start of colon cancer screening was lowered from age 50 to age 45 in average risk populations.

Screening for colorectal cancer improves prognosis for patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer because screening generally identifies early-stage CRC that is easier to treat and has a lower mortality rate than CRC that is detected after symptoms occur.

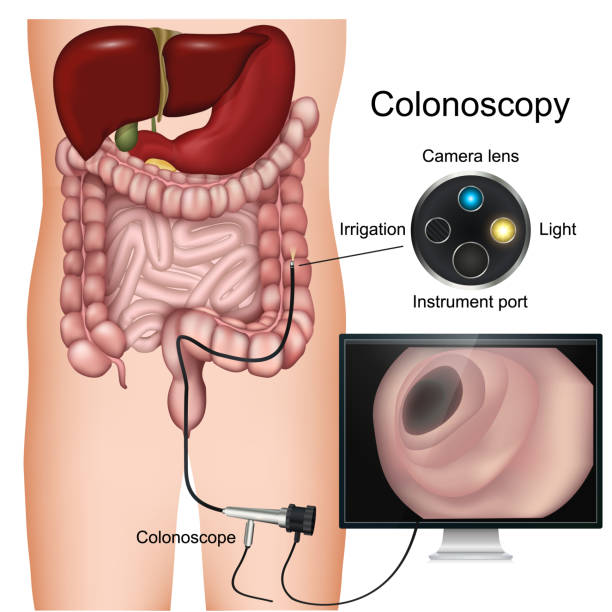

While CRC screening has benefits, as listed above, there are potential harms, like any testing. Any abnormal test results from screening tests OTHER than colonoscopy (we discuss various screening tests below) will then necessitate a colonoscopy be done. Thus, all screening modalities are associated with the potential for need for colonoscopy and, thus, colonoscopy-associated complications. What are the risks of colonoscopy? Answer: Perforation, Infection, and Cost.

What age to Screen for colorectal cancer?

Average Risk patients/No family history of colon cancer

- Start at age 45.

- Continue screening thru age 75 as long as life-expectancy is 10 years or greater.

- For patients aged 76-85 who have been screened before, individualized decision-making should occur (shared decision making with provider/patient) about whether to continue screening based upon the patient’s preference, prior test results (polyps, etc.), and patient comorbidities.

- For patients aged 76-85 who have never been previously screened, a one-time screening appears to be cost effective up to an age that varies depending on the patient’s life-expectancy.

Patients with a family history of colon cancer

- Start screening at age 45 or at an age 10 years younger than the person in the family who had colorectal cancer was at the time of their diagnosis, WHICHEVER age is younger. For example, if your patient had an uncle with colon cancer at age 60, your patient should start colon cancer age 45. However, if their uncle had colon cancer at age 50, you would start their CRC screening at age 40.

- Continue screening thru age 75 as long as life-expectancy is 10 years or greater.

- For patients aged 76-85 who have been screening before, individualized decision-making should occur (shared decision making with provider/patient) whether to continue screening based upon the patient’s preference, prior test results (polyps, etc.), and patient comorbidities.

- For patients aged 76-85 who have never been previously screened, a one-time screening appears to be cost effective up to an age that varies depending on the patient’s life-expectancy.

You do need to know the general screening ages as recommended above.

Patients with a strong family history of colon cancer: Patients with a family history of 3 or more cases of colorectal cancer (or other cancers concerning for a genetic syndromes) should be referred for genetic counseling to determine if they should be tested for a genetic syndrome. If they are ultimately found to have a genetic syndrome, then their screening will be very different. Generally, this is managed by a genetic counselor or by the Primary Care Provider with input/recommendations from the genetic counselor. It is unclear what to do with patients with a family history of 2 colorectal cancers, but this likely depends on the size of their family and the ages at the time of diagnosis of the family members who had cancer. You do not need to know about this variation for this class.

What are the colorectal cancer screening test options for average risk patients?

- Colonoscopy every 10 years. This is the Gold standard and is the preferred screening test. Note that if polyps are found at the time of colonoscopy, they are removed. Hence, colonoscopy is also thought to be preventative for colorectal cancer by removing polyps before they become cancerous. If polyps are found, then subsequent colonoscopies will be done sooner than 10 years, and the frequency is defined by the number and type of polyps found. If the colonoscopy is normal, then the frequency of colonoscopy continues to be every 10 years.

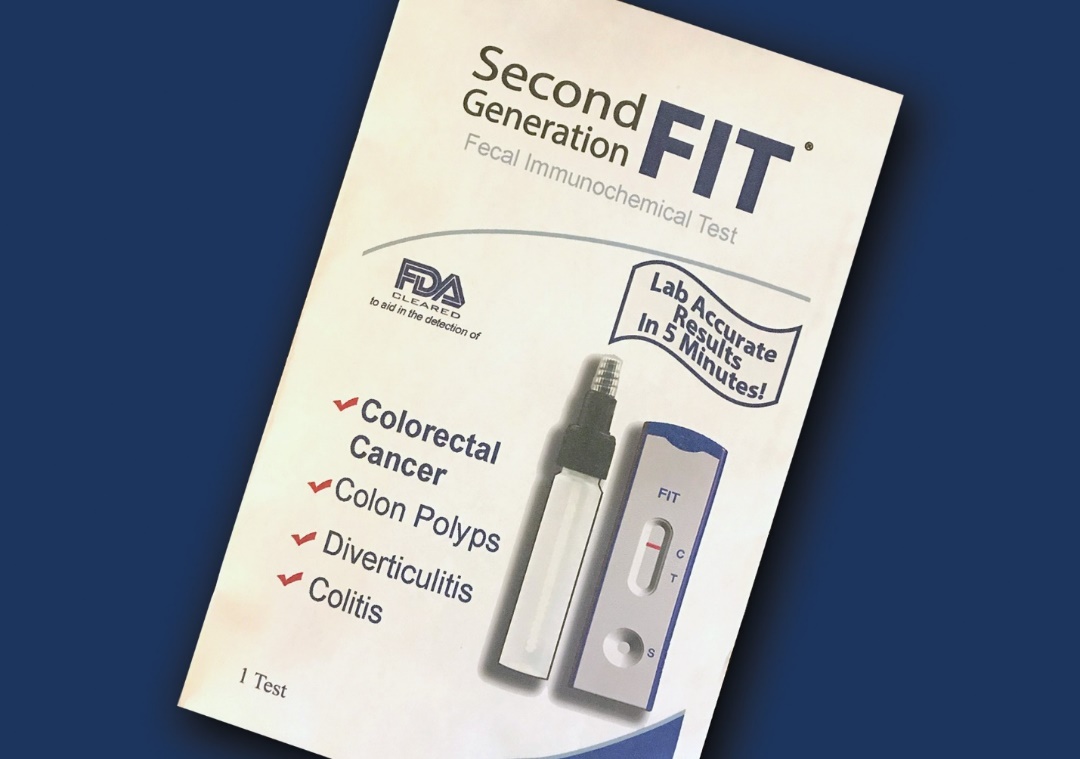

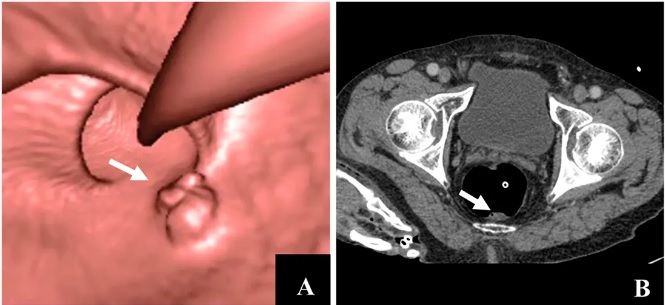

(Image courtesy of iStock) - Fecal Immunochemical testing (FIT) for occult blood ANNUALLY. If a patient opts for this testing, it is important for them to be aware that this test must be done yearly for it to be an effective screening modality. Also, if the FIT test comes back positive, then a colonoscopy must be done promptly.

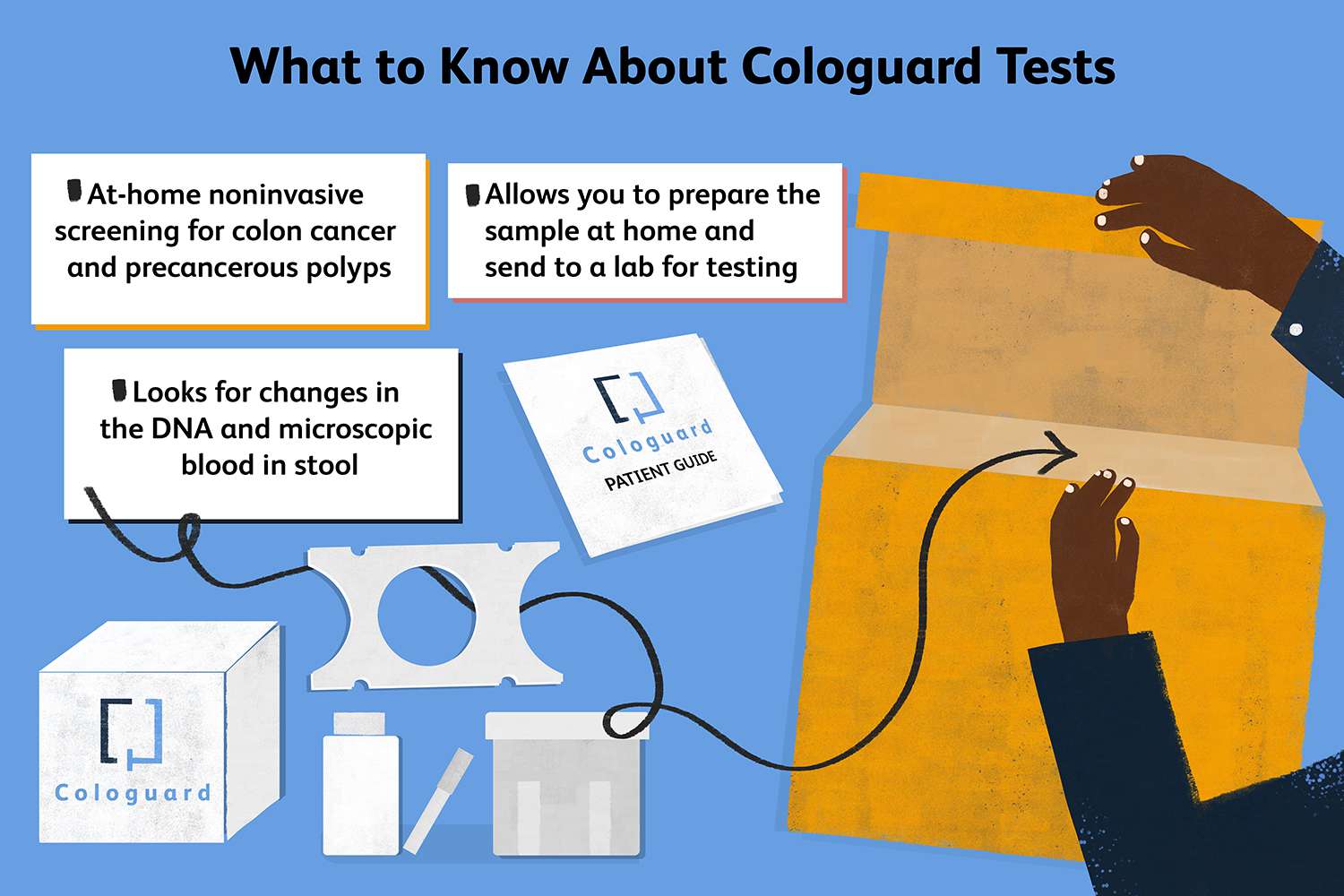

- Multitarget stool DNA testing (Cologuard) every 3 years. This is a test that combines FIT and multitarget fecal DNA testing (it includes both fecal markers for hemoglobin and DNA mutation and methylation). This testing is performed every 3 years on one entire collected stool sample, and it is important for patients to understand this must be done very 3 years to be an effective screening modality. If it is abnormal, then a colonoscopy needs to be done promptly.

(Image courtesy of Verywell Health) - Computed tomography colonography (CT colonography) every 5 years. This test is also called a virtual colonoscopy. It must be done very 5 years to be an adequate screening modality, and it requires the same type of bowel prep as a colonoscopy. If concerning findings are noted on this test, then a colonoscopy must be performed promptly.

(Image courtesy of Wikipedia)

Other less desirable/outdated colon cancer screening options

Sigmoidoscopy every 5 to 10 years along with an annual FIT test.

Sigmoidoscopy alone every 5 to 10 years, but this will miss lesions proximal to 60 cm from the anus. Women and older patients have a higher frequency of more proximal colon lesions that will be missed by this method.

Guiaic-based fecal occult blood testing annually. If this option is used for colon cancer screening, it is preferable to use the “sensitive gFOBT (Fecal Occult Blood Test), example the Hemoccult SENSA test. gFOBT is done annually on 3 samples as a take-home test that the patient mails back, rather than on stool obtained in the office during a digital rectal examination (DRE). It typically takes the patient 3 days to collect the test—as samples from 3 different stools are required.

Capsule colonoscopy. Note, a bowel prep is needed, but sedation is not needed with this (sedation is OPTIONAL for colonoscopy and doesn’t have to be given if the patient doesn’t want sedation).

ASIDE: What is the difference between a Guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) and a FIT test?

Answer:

- Guaiac testing identifies hemoglobin (in stool in this type of testing) by turning guaiac reagent-impregnated paper blue as the result of a peroxidase reaction. Large doses of vitamin C may cause a false negative test. In studies, Guaiac-based may be less-effective for detection of CRC and advanced adenomas.

- The Fecal Immunochemical test (FIT) directly measures hemoglobin in the stool. It requires only 1 stool sample (as opposed to Guaiac-based, which ideally requires 3 different samples). Foods with peroxidase activity don’t cause a false positive FIT.

Tests that are no longer recommended for CRC screening

Screening tests that are no longer recommended for colon cancer screening include the following: Digital rectal exam (DRE), office-based gFOBT after DRE, and barium enema.

Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening

- Need for a primary care doctor to order the tests. Patients can’t just walk in and order a FIT test, for example. Patients can directly schedule a colonoscopy unless their insurance requires a referral from a PCP. However, most patients don’t realize that they can call a GI doc directly to schedule this and don’t know about the test.

- Cost: The best tests, particularly colonoscopy, are expensive.

- Patients need a bowel prep for certain procedures (colonoscopy, virtual colonoscopy).

- Logistics of a colonoscopy: the prep to do before the test, the need for a driver if sedation is desired (most patients use sedation, but it is important to know that sedation is optional), need for childcare in order for the patient to go in for the procedure, etc.

- Socioeconomic: Time off from work for colonoscopy/other procedures, childcare costs, need for a driver if sedation required, language barriers, cultural preferences.

- Patient reluctance to have a colonoscopy done: Prep takes a few days (includes a special diet for a few days and then a bowel clean-out preparation that starts the day prior to the procedure). Patients often are concerned about the actual colonoscopy procedure (“Doc, do you really want me to have a garden hose run up my bowel? Do they clean that garden hose before they put it up someone else’s bowel?”)

Lung cancer Prevention and Screening

Before we go into details about lung cancer screening, a reminder that prevention, rather than screening, is the most effective strategy for reducing the burden of lung cancer in our society. There are two key areas of lung cancer prevention that should be addressed by physicians/all health care providers:

- Smoking cession

- Radon Mitigation (note Spokane and surrounding areas have a high amount of radon in the earth compared to other areas, so radon mitigation is required with home sales, etc).

With the above in mind, a high percentage of lung cancers do occur in smokers and former smokers. Hence, screening for lung cancer is recommended in smokers/former smokers based upon very specific guidelines (which are based on a published clinical trial for lung cancer screening).

Lung cancer screening is a newer screening tool, compared to breast, prostate, and colon cancer screening concepts above. Lung cancer screening has been poorly adopted by the medical community, and only about 15% of eligible patients actually get screened. You future doctors can hopefully change this as you go into practice!

Summary of Key findings/ongoing questions from Lung Cancer Screening Studies

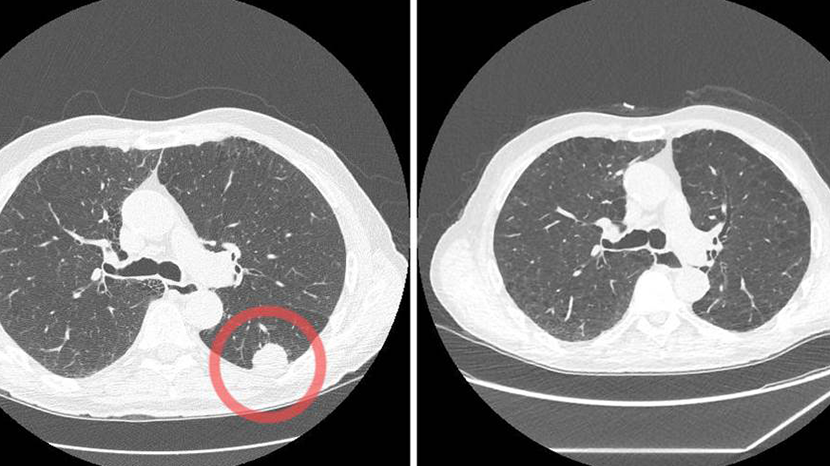

- CXR (chest X-ray) screening does NOT reduce mortality from lung cancer. Hence, lung cancer screening using plain X-rays is not recommended.

- Low dose chest CT (computed tomography) screening is significantly more sensitive than CXR for identifying small, asymptomatic lung cancers.

- CXR and low dose CT screening have high rates of false-positive findings leading to additional testing that usually includes serial imaging but may include invasive procedures such as biopsy. Other incidental findings may be found with CXR and low dose CT screening, most commonly emphysema and coronary artery calcifications.

- The National Lung Screening Trial, which was a trial of low dose chest CT vs CXR) showed a lung cancer mortality benefit of 20% with all-cause mortality reduced by 6.7%.

- The question of cost-effectiveness of screening with low dose chest CT remains a major issue because of the significant costs associated with screening and follow up of the many false-positive tests.

- Questions remain re: optimal screening frequency (how often to screen), duration (what ages to screen or how many years after one quits smoking, etc.), and appropriate population targets (active smokers, passive smokers, smokers who quit, etc.). In addition, there remains questions about how we define a “positive” result and then identify follow up protocols for questionable findings.

- Multiple societies have issued guidelines for cancer screening, with some mild variations. These societies include the American Association of Thoracic Surgery, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Canadian task Force on the Periodic Health Examination, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the US Preventive Services Task Force, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Given all the above, it is important to realize that we have more to learn about lung cancer screening. However, from the main study on low dose-CT scans, we can take away the following general recommendation:

Recommendations for Lung cancer Screening

General recommendation (there are variations in various expert groups, but this is most accepted):

- No screening for low or moderate risk individuals (IE, individuals who aren’t high risk).

- Screening is recommended for high-risk individuals, as defined as follows:

- Age 50-80 with a 20 or more pack-year history of smoking AND who continue to smoke.

- Age 50-80 with a 20 or more pack-year history of smoking who quit smoking within 15 years.

Screening should be annually with a low-dose helical CT. Screening should be discontinued once the individual has not smoked for 15 years or has a limited life expectancy such that further screening would likely not impact life expectancy.

Note, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services (often a guide of what Medicare insurance will cover) recommend annual low-dose Ct scan screening after completion of a shared decision-making visit for higher-risk individuals (ages 50-77 years with a greater than or equal to 20 pack-year history of smoking and either continues to smoke OR has quit within the past 15 years.

Barriers to Lung Cancer Screening

- Cost

- Concerns about radiation exposure from CT scans. It has been estimated that for every 108 lung cancers discovered by screening., one major cancer would be induced by radiation.

- Guidelines for lung cancer screening are not commonly known.

- Lack of a primary care physician to order the CT scan.

- Socioeconomic: No insurance, need to take time off from work for the test, need for transportation to the CT scan, need for childcare, location of radiology services, etc.

Summary of Cancer Screening recommendations in Average Risk patients in the USA

- Breast cancer screening with mammogram warranted in cisgender women aged 40 and over, with discussion with patients about risks and benefits. Transgender women are recommended to have breast cancer screening starting at age 50 if they have additional risks for breast cancer. Transgender men with breasts should be screened as per natal females.

- Prostate cancer screening remains controversial as to benefits and warrants shared decision making between provider and patient. The age at which to initiate screening, if screening is chosen, varies from age 40 to 50, depending upon family history, race, and genetics.

- Colon cancer screening is warned in all patients aged 45 and higher (unless family history or genetics warrant that screening start earlier), with a discussion with the patient about which modality to use and risks/benefits.

- Lung cancer screening is warranted in high-risk patients as defined in studies and outlined above.

- Cervical cancer screening is warranted and is covered in the Lifecycles (OB/Gyn) session. General age to start screening for cervical cancer is age 21 in the USA, but guidelines vary. Note, Cervical cancer screening is not covered in the blood and cancer unit, but you should be aware that this is a screening test that is generally recommended for cancer screening. You should also be aware that cervical cancer screening recommendations differ in resource-rich countries like the USA vs resource-limited countries. World-wide, cervical cancer is the 4th most common cancer in females and 85 % of new cases are diagnosed in resource-limited countries.

Summary Recommendations for Cancer Screening for Transwomen and Transmen

Cancer Screening in Transgender women (natal male to female transition, MTF)

- Breast cancer: Discuss/recommend screening in patients ages 50 or older who have additional risk factors for breast cancer, which include estrogen/progestin therapy for >5 years, family h/o breast cancer, body mass index (BMI) >35.

- Cervical cancer: No screening needed, even if vaginoplasty has been done, unless the patient has a transplanted uterus and cervix (exceedingly rare).

- Prostate cancer: Routine screening should be discussed with shared decision making as would be done for natal males.

- Lung cancer: Recommendations for screening are the same regardless of sex.

- Colon cancer: Recommendations for screening are the same regardless of sex.

Cancer Screening in Transgender men (natal female to male transition, FTM)

- Breast cancer: Transmen with intact breasts should have the same screening as would be done for natal females. In transmen who have undergone mastectomy, a yearly chest wall exam and axillary node exam is suggested by some authors as a pretext for discussing with patients that they still have a small risk for breast cancer in any remaining breast tissue in the chest wall or breast cancer in the nodes of the axillae, although the risk is quite low.

- Cervical cancer: Transmen with intact cervixes should have the same routine screening as is recommended for natal females. Transmen who don’t have a cervix (such as those who have had their uterus and cervix removed), don’t require cervical cancer screening.

- Prostate cancer: No screening needed.

- Lung cancer: Recommendations for screening are the same regardless of sex.

- Colon cancer: Recommendations for screening are the same regardless of sex.

Authors and Contributors: Corliss Newman, MD