3 The Interactions Between Human Community and Biodiversity

Xinzhe Wang

The Interactions Between Humans and Biodiversity

Biodiversity is considered to be the full range of life in all forms, which includes the habitats and their interactions with the species. Biodiversity plays an extremely crucial role in the process that supporting all life on the earth. In this chapter, two important aspects that influence the human community in Pacific Northwest forests will be depicted, which are human activity and local culture.

In the Pacific Northwest region, there is a massive scale of natural resources. In terms of using resources, a lot of human activities are occurring in PNW forests to gain resources for sustaining people’s daily life, such as logging or building dams. The problem is that varied destruction can be added onto the environment during the process of gaining natural resources and affect a series of species living down there. From a cultural aspect, people who live in PNW regions significantly depend on the local environment and biodiversity to support their livelihoods which have continued for thousands of years. More importantly, the cultural values towards nature that local tribes have always believed in, have created a profound impact on people till today.

One typical natural resource in PNW forests is trees. Commercial logging was one of the earliest and largest industries in PNW forests, and it was facilitated rapidly from the 1840s as settlers moved in. A notable number of trees were logged in riparian forests because wood could be transported to sawmills much easier by water. Heavy riparian logging reduced vegetation cover and engendered problems such as erosion and sedimentation. As the logging industry rose remarkably in World War II, more advanced equipment was introduced, and roads along the streams were built, which increased logging speed and expanded the logging area. Many species that spawn in the streams (such as salmon and steelhead) were negatively affected by logging practices, through water quality degradation when building roads, and decreased vegetation cover along the stream which led to an increase in water temperature. Furthermore, riparian conditions were also affected by building roads for logging. In steep terrains, landslides due to road construction could block streams or deposit layers of silt easily, and logged hillsides lost their original capability to hold rainwater and snow. Consequently, flooding can be triggered easily. Slash and woody debris dumped into streams also affected fish and wildlife habitats by blocking access for fish. Even though change has been made and efforts were put into improving environmental and biodiversity protection in recent years, such as practicing logging in sustainable and wildlife-conserving ways, there are still problems waiting for solutions. [1] To know more about logging, please read the chapter: “Logging In Relation To Forests”.

With the rising amount of conversion of natural land for human use, habitat fragmentation escalates also. Does habitat fragmentation influence biodiversity? A quote from Wilcox begins to provide the answer “Habitat fragmentation is the most serious threat to biological diversity, and the primary cause of the present extinction event”[2]. The formation of habitat fragmentation could be caused by both natural (wildfire or volcanic eruption) and human activity, but human is the main contributor. Habitat fragmentation is formed when parts of a piece of habitat are disturbed or ruined, and a smaller area is divided apart from or unconnected to the original whole habitat. Three main impacts of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity are

1) Lower habitat quality: as habitats are broken into parts, some species might be adapted to broken pieces of habitat, but some others might be struggled to survive within the fragmentation.

2) Enlarged risks of invasive species: smaller “leftovers” of habitat and more exposure of edges make it easier for foreign species to invade and replace the original local species.

3) Due to the first and second reasons, extinction risks for some certain species soar incredibly.[3]

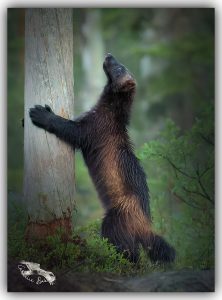

Wolverine is one of the most endangered populations in PNW regions. The number of wolverines in the United States is under 300, reasons for this are hunting, climate change, and chiefly habitat fragmentation. Wolverines’ habitat has been degraded by human activities, including logging, oil exploitation, and especially roads. Wolverines need large-scale, connected, and completed habitats to survive, while roads have cut up key parts of supreme habitats. Nevertheless, people can still contribute to reconnecting habitats for wolverines by removing abandoned roads and constructing wildlife bridge, which not only cost relatively less money for human but also makes a huge difference in improving wildlife habitats. [4]

Another endangered species in PNW is the pygmy rabbit. The major reason for the tumbling population of this species is also habitat fragmentation. Especially habitat fragmentation caused by roads, one important factor which can influence on sagebrush population has an interesting relationship with the traffic volume. Sagebrush reproduces via birds passing through its seeds, and to a certain extent, birds might be affected by traffic noise and dust. [5] Extensive sagebrush-covered land plays a considerable role in the ideal habitat for the pygmy rabbits and many other species, and also for local tribes. Sagebrush is a natural resource both ecologically and culturally important in the PNW region. Sagebrush is one of the most meaningful and far-reaching ceremonial plants in local tribes’ culture. Local people love to use sagebrush to make incense and purify herbs. Sagebrush is also a symbol of healing and safety and is believed to clean off evil things and get rid of bad luck. Moreover, sagebrush has been used as medicine for thousands of years in local tribes, which can treat varied illnesses such as headaches, stomach ailments, and even post-partum pain suffered by new mothers. [6]

In addition, as mentioned above, logging has substantially contributed to the declining population of salmon, the typical representation of PNW, and the cultural lifeblood of numerous local tribes. Unfortunately, logging is not the only reason, but also includes many other numberless human activities (overfishing, building dams, climate change, etc.). To be right to the point, people who contributed the least amount of destruction to nature, are suffering the most from the consequences. One quintessential example is fishing rights. Native tribes used to be restricted from fishing, because of the competition for resources, and this is why the term “climate justice movement” was invented for. (To know more about climate justice, please read the chapter: “Climate Justice and Health Impacts) Even though native people gained back the fishing rights afterward, the crisis of salmon remained to them, as salmon is one of the most important resources for them to survive. Nevertheless, biodiversity conservation and implementing sustainability are one of our common goals today. “Traditional knowledge,” says Robinson, “is one of our key values. Tribes have been here for tens of thousands of years; others have been here for a few hundred. Through all those years the tribes have been outstanding stewards and maintained a deep, abiding respect for nature and the resources around us. There are important messages coming out of knowledge transferred from one generation to the next.”[7] Ocean provides native people with their main food source. There’s no waste during their food production due to the close relationships between families and tribes, that they exchange varied resources each other needs. In particular, native people profoundly depend on nature to survive, and accordingly, the connection between people and land has always been a paramount idea in their culture.[8]

It may take several years or decades for humans to realize the various effects of human activities on nature, just as humans discovered the logging practice in the nineteenth century had actually taken place and resulted in the decreasing population of certain fish species and soil erosion that we see today. A variety of factors can be involved in relation to a single natural phenomenon observed by humans. Nature’s complexity is beyond human comprehension, and everything is interconnected.

- Harrison, John. “Logging.” Northwest Power and Conservation Council, https://www.nwcouncil.org/reports/columbia-river-history/logging/. ↵

- Stewart, Brian C., and Name. “Waking the ‘Sleeping Giant’: An Introduction to Road Ecology and Habitat Fragmentation in Washington State.” Urban Ecology, Evergreen State College, 1 Mar. 2018, https://sites.evergreen.edu/urbanecologyw18/waking-the-sleeping-giant-an-introduction-to-road-ecology-and-habitat-fragmentation-in-washington-state/. ↵

- Martin, James. “What Is Habitat Fragmentation and What Does It Mean for Wildlife?” Woodland Trust, 16 Aug. 2018, https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/blog/2018/08/what-is-habitat-fragmentation-and-what-does-it-mean-for-our-wildlife/. ↵

- Jason T Fisher Adjunct Professor; Head, and Aerin Jacob Adjunct professor. “Connecting Fragmented Wolverine Habitat Is Essential for Their Conservation.” The Conversation, 17 May 2022,https://theconversation.com/connecting-fragmented-wolverine-habitat-is-essential-for-their-conservation-179151 ↵

- Ingelfinger, Franz, and Stanley Anderson. “PASSERINE RESPONSE TO ROADS ASSOCIATED WITH NATURAL GAS EXTRACTION IN A SAGEBRUSH STEPPE HABITAT.” JSTOR, Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Aug. 2004, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41717388?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↵

- Ryan, Terry. “The Story behind Sagebrush, an Icon of the West.” Montana Public Radio, 1 May 2017, https://www.mtpr.org/arts-culture/2017-05-01/the-story-behind-sagebrush-an-icon-of-the-west. ↵

- Wall, Dennis. “Tribes: Pacific Northwest Fisheries Impact.” Tribes: Northwest - Tribes & Climate Change, Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals, Northern Arizona University, with Financial Support from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2008, https://www7.nau.edu/itep/main/tcc/Tribes/pn_fisheries. ↵

- Fletcher, Garry, and Sarah C. Fletcher. “The First Nations of the North West Coast- Coast Salish; Connections to the Environment, Involvement in Conservation.” Race Rocks Ecological Reserve, McGill University, 17 Apr. 2000, https://racerocks.ca/the-first-nations-of-the-north-west-coast-coast-salish-connections-to-the-environment-involvement-in-conservation/. ↵