7.6 Media Influence on Laws and Government

Media have long had a voice and a role in politics. As you have read in earlier chapters, even some of the earliest newspapers and magazines used their pages as a forum for political discourse. When broadcast media emerged during the 20th century, radio briefs and television reports entered the conversation, bringing political stories to the public’s living rooms.

In addition to acting as a watchdog, media provide readers and viewers with news coverage of issues and events, and also offer public forums for debate. Thus, media support—or lack thereof—can have a significant influence on public opinion and governmental action. In 2007, for example, The Washington Post conducted a 4-month investigation of the substandard medical treatment of wounded soldiers at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC. Because of the ensuing two-part feature, the Secretary of the Army and the two-star general in charge of the medical facility lost their jobs.

However, an ongoing debate exists over media’s role in politics. Many individuals wonder who is really behind certain stories. William James Willis, author of The Media Effect: How the News Influences Politics and Government discusses this debate:

Sometimes the media appear willing or unwitting participants in chasing stories the government wants them to chase; other times politicians find themselves chasing issues that the media has enlarged by its coverage. Over the decades, political scientists, journalists, politicians, and political pundits have put forth many arguments about the media’s power in influencing the government and politicians (Willis, 2007).

Regardless of who is encouraging whom, media coverage of politics certainly raises questions among the public. Despite laws put in place to prevent unbalanced political coverage, such as Section 315, a large majority of the public is still wary of the media’s role in swaying political opinion. In a January 2010 survey, two-thirds of respondents said that the media has too much influence on the government. Additionally, 72 percent of respondents agreed that “most reporters try to help the candidate they want to win (Rasmussen Reports, 2010).” This statistic demonstrates the media’s perceived political power along with the road the media must carefully navigate when dealing with political issues.

Propaganda and Other Ulterior Motives

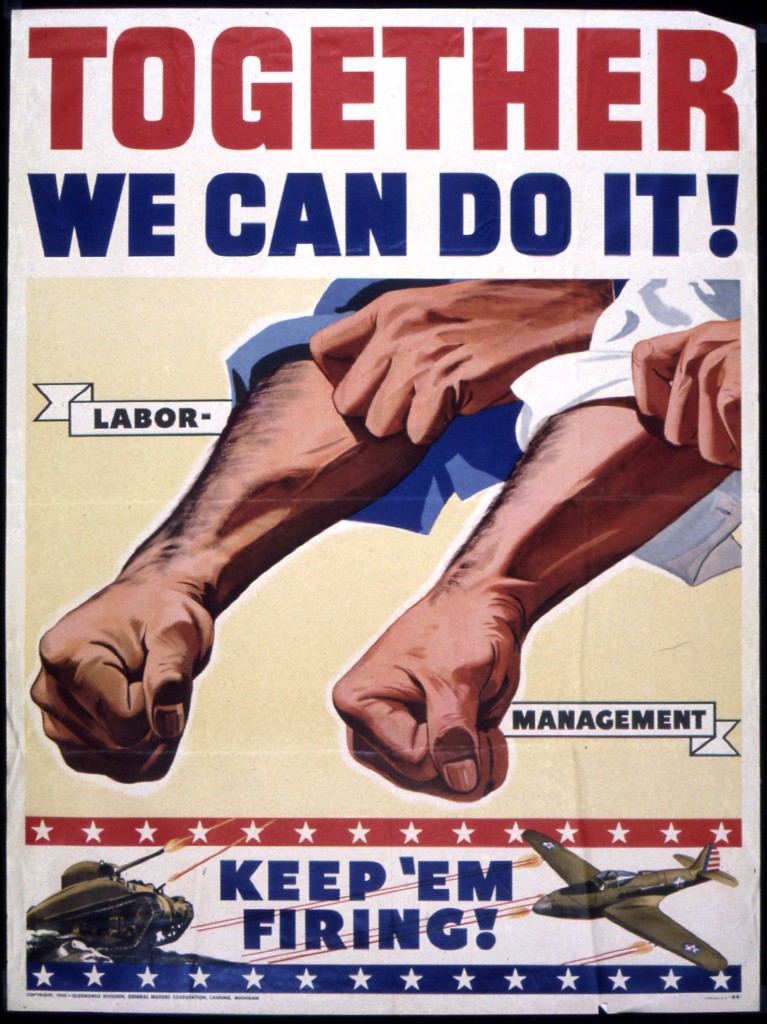

Sometimes social values enter mass media messages in a more overt way. Producers of media content may have vested interests in particular social goals, which, in turn, may cause them to promote or refute particular viewpoints. In its most heavy-handed form, this type of media influence can become propaganda, communication that intentionally attempts to persuade its audience for ideological, political, or commercial purposes. Propaganda often (but not always) distorts the truth, selectively presents facts, or uses emotional appeals. During wartime, propaganda often includes caricatures of the enemy. Even in peacetime, however, propaganda is frequent. Political campaign commercials in which one candidate openly criticizes the other are common around election time, and some negative ads deliberately twist the truth or present outright falsehoods to attack an opposing candidate.

Other types of influence are less blatant or sinister. Advertisers want viewers to buy their products; some news sources, such as Fox News or The Huffington Post, have an explicit political slant. Still, people who want to exert media influence often use the tricks and techniques of propaganda. During World War I, the U.S. government created the Creel Commission as a sort of public relations firm for the United States’ entry into the war. The Creel Commission used radio, movies, posters, and in-person speakers to present a positive slant on the U.S. war effort and to demonize the opposing Germans. Chairman George Creel acknowledged the commission’s attempt to influence the public but shied away from calling their work propaganda:

In no degree was the Committee an agency of censorship, a machinery of concealment or repression…. In all things, from first to last, without halt or change, it was a plain publicity proposition, a vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world’s greatest adventures in advertising…. We did not call it propaganda, for that word, in German hands, had come to be associated with deceit and corruption. Our effort was educational and informative throughout, for we had such confidence in our case as to feel that no other argument was needed than the simple, straightforward presentation of the facts (Creel, 1920).

Of course, the line between the selective (but “straightforward”) presentation of the truth and the manipulation of propaganda is not an obvious or distinct one. (Another of the Creel Commission’s members was later deemed the father of public relations and authored a book titled Propaganda.) In general, however, public relations is open about presenting one side of the truth, while propaganda seeks to invent a new truth.

Gatekeepers

In 1960, journalist A. J. Liebling wryly observed that “freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Liebling was referring to the role of gatekeepers in the media industry, another way in which social values influence mass communication. Gatekeepers are the people who help determine which stories make it to the public, including reporters who decide what sources to use and editors who decide what gets reported on and which stories make it to the front page. Media gatekeepers are part of society and thus are saddled with their own cultural biases, whether consciously or unconsciously. In deciding what counts as newsworthy, entertaining, or relevant, gatekeepers pass on their own values to the wider public. In contrast, stories deemed unimportant or uninteresting to consumers can linger forgotten in the back pages of the newspaper—or never get covered at all.

In one striking example of the power of gatekeeping, journalist Allan Thompson lays blame on the news media for its sluggishness in covering the Rwandan genocide in 1994. According to Thompson, there weren’t many outside reporters in Rwanda at the height of the genocide, so the world wasn’t forced to confront the atrocities happening there. Instead, the nightly news in the United States was preoccupied by the O. J. Simpson trial, Tonya Harding’s attack on a fellow figure skater, and the less bloody conflict in Bosnia (where more reporters were stationed). Thompson went on to argue that the lack of international media attention allowed politicians to remain complacent (Thompson, 2007). With little media coverage, there was little outrage about the Rwandan atrocities, which contributed to a lack of political will to invest time and troops in a faraway conflict. Richard Dowden, Africa editor for the British newspaper The Independent during the Rwandan genocide, bluntly explained the news media’s larger reluctance to focus on African issues: “Africa was simply not important. It didn’t sell newspapers. Newspapers have to make profits. So it wasn’t important (Thompson, 2007).” Bias on the individual and institutional level downplayed the genocide at a time of great crisis and potentially contributed to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Gatekeepers had an especially strong influence in old media, in which space and time were limited. A news broadcast could only last for its allotted half hour, while a newspaper had a set number of pages to print. The Internet, in contrast, theoretically has room for infinite news reports. The interactive nature of the medium also minimizes the gatekeeper function of the media by allowing media consumers to have a voice as well. News aggregators like Digg allow readers to decide what makes it on to the front page. That’s not to say that the wisdom of the crowd is always wise—recent top stories on Digg have featured headlines like “Top 5 Hot Girls Playing Video Games” and “The girl who must eat every 15 minutes to stay alive.” Media expert Mark Glaser noted that the digital age hasn’t eliminated gatekeepers; it’s just shifted who they are: “the editors who pick featured artists and apps at the Apple iTunes store, who choose videos to spotlight on YouTube, and who highlight Suggested Users on Twitter,” among others (Glaser, 2009). And unlike traditional media, these new gatekeepers rarely have public bylines, making it difficult to figure out who makes such decisions and on what basis they are made.

Observing how distinct cultures and subcultures present the same story can be indicative of those cultures’ various social values. Another way to look critically at today’s media messages is to examine how the media has functioned in the world and in the United States during different cultural periods.

Politics, Broadcast Media, and the Internet

Throughout their respective histories, radio, television, and the Internet have played important roles in politics. As technology developed, citizens began demanding greater levels of information and analysis of media outlets and, in turn, politicians. Here we explore the transformation of politics with the development of media.

Radio

As discussed in Chapter 7 “Radio”, radio was the first medium through which up-to-the-minute breaking news could be broadcast, with its popularization during the 1920s. On November 2, 1920, KDKA in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, became the first station to broadcast election results from the Harding-Cox presidential race, “becoming a pioneer in a brand new technology (American History).” Suddenly, information that would previously have been available only later in the newspapers was transmitted directly into American living rooms. The public responded positively, wanting to be more involved in U.S. politics.

As radio technology developed, “Americans demanded participation in the political and cultural debates shaping their democratic republic (Jenkins).” Radio provided a way to hold these debates in a public forum; it also provided a venue for politicians to speak directly to the public, a phenomenon that had not been possible on a large scale prior to the invention of the radio. This dynamic changed politics. Suddenly, candidates and elected officials had to be able to effectively communicate their messages to a large audience. “Radio brought politicians into people’s homes, and many politicians went to learn effective public-speaking for radio broadcasts (ThinkQuest).”

Television

Today, television remains Americans’ chief source of political news, a relationship that dates back almost to the very beginning of the medium. Political candidates began using TV commercials to speak directly to the public as early as 1952. These “living room candidates,” as they are often called, understood the power of the television screen and the importance of reaching viewers at home. In 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first candidate to harness television’s popularity. Eisenhower stepped onto the television screen “when Madison Avenue advertising executive Rosser Reeves convinced [him] that short ads played during such popular TV programs as I Love Lucy would reach more voters than any other form of advertising. This innovation had a permanent effect on the way presidential campaigns are run (Living Room Candidate).”

Nixon–Kennedy Debates of 1960

The relationship between politics and television took a massive step forward in 1960 with a series of four televised “Great Debates” between presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Seventy million U.S. viewers tuned into the first of these on September 26, 1960. The debates gave voters their first chance to see candidates debate, marking television’s entry into politics.

Just as radio changed the way politicians thought about their speeches, television emphasized the importance of their appearance. Shortly before the first debate, Nixon had spent 2 weeks in the hospital with a knee injury. By the day of the debate he was extremely underweight. In addition, he wore an ill-fitting shirt and refused to wear makeup. Kennedy, however, was fit, tan, and confident. The visual difference between the two candidates was staggering; Kennedy appeared much more presidential. Indeed, those who watched the first broadcast declared that Kennedy had clearly won the debate, while those who listened by radio said that Nixon had won. A record number of viewers watched the debates, and many historians have attributed Kennedy’s success at the polls that November to the public perception of the candidates formed during these debates (Mary Ferrell Foundation).

War and Television

Later in the decade, rising U.S. involvement in Vietnam brought television and public affairs together again in a significant way. The horrors of battle were broadcast directly into U.S. homes on a large scale for the first time; although television had been invented prior to the Korean War, “the medium was in its infancy…[and] its audience and technology [were] still too limited to play a major role (Museum of Broadcast Communications).” As such, in 1965 the Vietnam War became the first “living-room war.”

Early in the war, the coverage was mostly upbeat:

It typically began with a battlefield roundup, written from wire reports based on the daily press briefing in Saigon…read by the anchor and illustrated with a battle map…. The battlefield roundup would normally be followed by a policy story from Washington, and then a film report from the field…. As with most television news, the emphasis was on the visual and above all the personal: “American boys in action” was the story, and reports emphasized their bravery and their skill in handling the technology of war (Museum of Broadcast Communications).

In 1969, however, television coverage began to change as journalists grew more and more skeptical of the government’s claims of progress, and there was more emphasis on the human costs of war (Museum of Broadcast Communications). Although gore typically remained off screen, a few major violent moments were caught on film and broadcast into homes. In 1965, CBS aired footage of U.S. Marines setting village huts on fire, and in 1972, NBC audiences witnessed Vietnamese civilians fall victim to a napalm strike. Such scenes altered America’s perspective of the war, generating antiwar sentiment.

Political News Programming

The way that news is televised has dramatically changed over the medium’s history. For years, nightly news broadcasts dominated the political news cycle; then round-the-clock cable news channels appeared. Founded by Ted Turner in 1980, CNN (Cable News Network) was the first such network. Upon the launch of CNN, Turner stated, “We won’t be signing off until the world ends. We’ll be on, and we will cover the end of the world, live, and that will be our last event…and when the end of the world comes, we’ll play ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ before we sign off (TV Tropes).”

Twenty-four-hour news stations such as CNN have become more popular, and nightly news programs have been forced to change their focus, now emphasizing more local stories that may not be covered by the major news programs. Additionally, the 21st century has seen the rise of the popularity and influence of satirical news shows such as The Daily Show and The Colbert Report. The comedic news programs have, in recent years, become major cultural arbiters and watchdogs of political issues thanks to the outspoken nature of their hosts and their frank coverage of political issues.

Online News and Politics

Finally, the Internet has become an increasingly important force in how Americans receive political information. Websites such as the Huffington Post, Daily Beast, and the Drudge Report are known for breaking news stories and political commentary. Additionally, political groups regularly use the Internet to organize supporters and influence political issues. Online petitions are available via the Internet, and individuals can use online resources to donate to political causes or connect with like-minded people.

Media and government have had a long and complicated history. Each influences the other through regulations and news cycles. As technology develops, the relationship between media and politics will likely become even more intermeshed. The hope is that the U.S. public will benefit from such developments, and both media and the government will seek out opportunities to involve the public in their decisions.

References

American History, “History of the Radio,” http://americanhistory.suite101.com/article.cfm/history_of_the_radio.

Creel, George.How We Advertised America (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920).

Glaser, Marc. “New Gatekeepers Twitter, Apple, YouTube Need Transparency in Editorial Picks,” PBS Mediashift, March 26, 2009, http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2009/03/new-gatekeepers-twitter-apple-youtube-need-transparency-in-editorial-picks085.html.

Jenkins, Henry. “Contacting the Past: Early Radio and the Digital Revolution,” MIT Communications Forum, http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/papers/jenkins_cp.html.

Living Room Candidate, Museum of the Moving Image, The Living Room Candidate, http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/.

Mary Ferrell Foundation, “Kennedy-Nixon Debates,” Mary Ferrell Foundation, http://www.maryferrell.org/wiki/index.php/Kennedy-Nixon_Debates.

Museum of Broadcast Communications, “Vietnam on Television,” http://www.museum.tv/eotvsection.php?entrycode=vietnamonte.

Rasmussen Reports, “67% Say News Media Have too Much Influence Over Government Decisions,” news release, January 14, 2010, http://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/politics/general_politics/january_2010/67_say_news_media_have_too_much_influence_over_government_decisions.

ThinkQuest, “Radio’s Emergence,” http://library.thinkquest.org/27629/themes/media/md20s.html.

Thompson, Allan. “The Media and the Rwanda Genocide” (lecture, Crisis States Research Centre and POLIS at the London School of Economics, January 17, 2007), http://www2.lse.ac.uk/publicEvents/pdf/20070117_PolisRwanda.pdf.

TV Tropes, “Twenty Four Hour News Networks,” http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/TwentyFourHourNewsNetworks.

Willis, William James. The Media Effect: How the News Influences Politics and Government (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007), 4.

Media texts whose purpose is not to inform rational critical societal debate, but to normalize a particular ideology.

People who determine which media messages, particularly but not just news stories, are made available for public consumption.