7.5 Digital Democracy and Its Possible Effects

The Role of Social Values in Internet-Based Communication

In a 1995 Wired magazine article, “The Age of Paine,” Jon Katz suggested that the Revolutionary War patriot Thomas Paine should be considered “the moral father of the Internet.” The Internet, Katz wrote, “offers what Paine and his revolutionary colleagues hoped for—a vast, diverse, passionate, global means of transmitting ideas and opening minds.” In fact, according to Katz, the emerging Internet era is closer in spirit to the 18th-century media world than to the 20th-century’s “old media” (radio, television, print). “The ferociously spirited press of the late 1700s…was dominated by individuals expressing their opinions. The idea that ordinary citizens with no special resources, expertise, or political power—like Paine himself—could sound off, reach wide audiences, even spark revolutions, was brand-new to the world (Creel, 1920).” Katz’s impassioned defense of Paine’s plucky independence speaks to the way social values and communication technologies are affecting our adoption of media technologies today. Keeping Katz’s words in mind, we can ask ourselves two additional questions: How do commonly-held values shape our ideas of what online communication should look like? And how, in turn, does the Internet change our understanding of what our society values?

In an era when work, discourse, and play are increasingly experienced via the Internet, it is fitting that politics have surged online as well in a recent phenomenon known as digital democracy. Digital democracy—also known as e-democracy—engages citizens in government and civic action through online tools. This new form of democracy began as an effort to include larger numbers of citizens in the democratic process. Recent evidence seems to confirm a rising popular belief that the Internet is the most effective modern way to engage individuals in politics. “Online political organizations…have attracted millions of members, raised tens of millions of dollars, and become a key force in electoral politics. Even more important, the 2004 and 2008 election cycles show that candidates themselves can use the Internet to great effect (Hindman, 2008).”

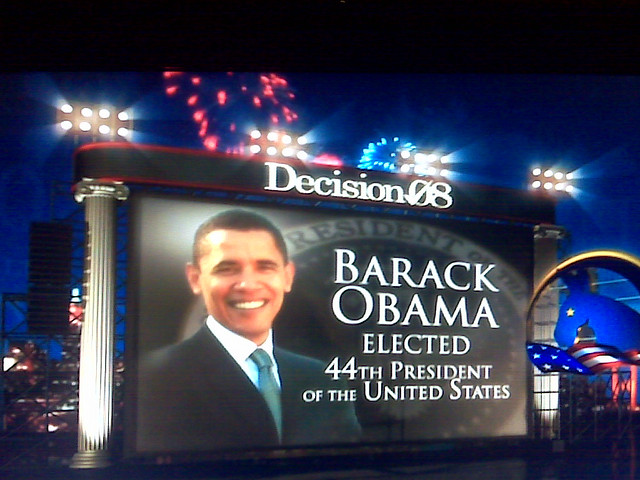

President Obama’s Digital Campaign

Perhaps the best example of a political candidate putting digital democracy to use is the successful 2008 presidential campaign of Barack Obama. On June 8, 2008, following Obama’s victory in the Democratic presidential primaries, The New York Times published an article discussing the candidate’s use of the Internet in his nomination bid. Titled “The Wiki-Way to the Nomination,” the article credits Obama’s success to his employment of digital technology: “Barack Obama is the victor, and the Internet is taking the bows (Cohen, 2008).”

Obama’s campaign certainly is not the first to rely on the Internet. Another Democratic presidential hopeful, Howard Dean, famously built his campaign online during the 2004 election cycle. But the Obama campaign took full advantage of the possibilities of digital democracy and, ultimately, secured the Oval Office partially on the strength of that strategy. As one writer puts it, “What is interesting about the story of his digital campaign is the way in which digital was integrated fully into the Obama campaign, rather than [being] seen as an additional extra (Williams, 2009).” President Obama’s successful campaign serves as an excellent example of the possibilities of digital democracy.

Traditional Websites

Several existing political websites proved beneficial to the Obama campaign. Founded in 1998, the liberal website MoveOn.org has long used its popularity and supporter base to mobilize citizens to vote, lobby, or donate funds to Democratic campaigns. With more than 4 million members, MoveOn.org plays a noticeable role in U.S. politics and serves as inspiration for other like-minded digital efforts.

The Obama campaign gave a nod to the success of such sites by building a significant web presence. Websites such as MyBarackObama.com formed the foundation of these online efforts. However, the success of the Obama digital campaign came from its use of online media in all its forms. The campaign turned not only to traditional websites but also to social networking sites, e-mail outreach, text messages, and viral videos.

Social Networking

More and more, digital democracy demands that its users rely on these alternative forms of Internet outreach. Social networking site Facebook was the hub of many digital outreach efforts during the 2008 campaign. As of 2010, Barack Obama’s official Facebook page boasts more than 9 million fans, and the Obama administration uses the page to send messages about the current political climate.

Individuals not part of the official campaign also established Facebook pages supporting the candidate. Mamas for Obama emerged just prior to the election, as did Women for Obama and the Michelle Obama Fan Club. The groups range in size, but all speak to a new wave of digital democracy. Other political candidates, including 2008 Republican presidential contender John McCain, have also turned to Facebook, albeit in less comprehensive ways.

E-Mail Outreach

The Obama campaign also relied on e-mail. In 2009, an article was published titled “The Story Behind Obama’s Digital Campaign” discussing the success of Obama’s use of the Internet. According to the article, 13.5 million people signed up for updates on Obama’s progress via the MyBarackObama.com website. The campaign regularly sent out e-mails to reach its audience.

Emails were short—never longer than 300 words—and never anonymous, there was always a consistency of voice and tone. Obama and other key figures in the campaign also contributed emails to be sent—“Michelle wrote her own emails…and more people opened those than her husband’s”—giving the campaign a personal touch and authenticity, rather than the impression of being simply churned out by the PR machine (Williams, 2009).

A combination of message and financial appeal, the e-mails were successful not only in reaching target audiences but also in earning valuable campaign dollars.

Two billion emails were then sent out, although…this email content was carefully managed, with individuals targeted with different “tracks” depending on their circumstances and whether they had already donated to the campaign…. By the end of the campaign the website had mobilized over 3 million people to contribute over $500 million online (Williams, 2009).

Text Messaging

Additionally, Obama used text messaging to reach out to his supporters. During the campaign, supporters could sign up to receive text messages, and attendees at rallies and other events were asked to send text messages to friends or potential supporters to encourage them to participate in Obama’s campaign. Members of MyBarackObama.com were the first to discover his running mate selection via text message (Organizing for America). This tool proved helpful and demonstrated the Obama campaign’s commitment to fully relying on the digital world.

E-Democracy

Perhaps even more impressive than the campaign’s commitment to digital democracy were the e-democracy efforts of Obama’s supporters. Websites such as Barackobamaisyournewbicycle.com, a gently mocking site “listing the many examples of Mr. Obama’s magical compassion. (‘Barack Obama carries a picture of you in his wallet’; ‘Barack Obama thought you could use some chocolate’),”1 emerged, but viral videos offered even stronger examples of Obama’s grassroots campaign.

One example of a supporter-created video was “Barack Paper Scissors,” an interactive game inspired by rock-paper-scissors. Posted on YouTube, the video logged some 600,000 views. The success of videos such as “Barack Paper Scissors” did not go unnoticed by the Obama campaign. The viral video “Yes We Can,” in which Barack Obama’s words were set to music by will.i.am (of the Black Eyed Peas), has been viewed more than 20 million times online. Capitalizing on the popularity of the clip, the campaign brought it from YouTube to its main website, thus generating even more views and greater exposure for its message.

Political Rumors Online

Although the Internet is a powerful tool for candidates, it also propagates rumors that can derail—or at least hinder—a politician’s career. Blog posts and mass e-mails can be created within minutes and then reposted or forwarded in seconds. Thus, ideas spread like wildfire regardless of their relative truth. Snopes.com, a website dedicated to verifying or debunking urban legends and Internet rumors, has an entire search section dedicated to political rumors, ranging from shooting down a list of books supposedly banned by Sarah Palin to investigating whether actress Nancy Cartwright, best known as the voice of Bart Simpson, was once elected mayor of Northridge, California. The pages dedicated to major political figures such as President Obama can be huge; Obama’s page, for example, lists more than 60 debunked rumors. Some of these rumors include the questioning of his U.S. citizenship, his decision to ban recreational fishing, and his refusal to sign Eagle Scout certificates.

Many of these online rumors are accompanied by “photographic evidence,” thanks to technology such as Photoshop, which allows photographs to be manipulated with the click of a mouse. With such a spread of online rumors, savvy media consumers must be wary of what they read and seek out legitimate sources of information to verify the news that they receive.

Digital Democracy and the Digital Divide

Just as digital technology access issues can create the kinds of problems discussed in Chapter 13 “Economics of Mass Media”, the digital divide can equally split the country’s involvement with politics along tech-savvy lines. Certainly, the Obama campaign’s reliance on modern technology allowed it to reach a large population of young voters; but in doing so, the campaign focused much of its attention in an area out of reach to other voters. In The Myth of Digital Democracy, author Matthew Hindman wonders, “Is the Internet making politics less exclusive?”2 The answer is likely both yes and no. While the Internet certainly has the power to inform and mobilize many individuals, it also denies poorer citizens without digital access an opportunity to be part of the new wave of e-democracy.

Nevertheless, digital democracy will continue to play a large role in politics, particularly after the overwhelming success of President Obama’s largely digital campaign. But politicians and their supporters must consider the digital divide and work to reach out to those who are not plugged in to the digital world.

Internet Censorship Around the World

Is what you see on the Internet being censored? In Chapter 11 “The Internet and Social Media”, you read about the debate between the search engine Google and China. However, Internet censorship is much more widespread, affecting people from Germany to Thailand to the United States. And now, thanks to a new online service, you can see for yourself.

In September 2010, Google launched its new web tool, Google Transparency. This program allows users to see a map of online censorship around the world. With this tool, people can view the number of times a country requests data to be removed, what kind of data they request be removed, and the percentage of requests that Google complies with. In some cases, the content is minor—YouTube videos that violate copyright, for example, are frequent offenders. In other cases, the requests are more formidable; Iran blocked all of YouTube after the disputed 2009 elections, and Pakistan blocked the site for more than a week in response to a 2010 online protest. Perhaps most surprising is the amount of requests from countries not normally associated with strict censorship. Germany, for example, has banned content it deems to be affiliated with neo-Nazism, and Thailand refuses to allow videos of its king that it finds offensive. Between January and June 2010, the United States asked Google 4,287 times for information regarding its users, and sent 128 requests to the search engine to remove data. Eighty percent of the time, Google complied with the requests for data removal (Sutter, 2010).

What is the general trend in Internet censorship? According to Google, it’s becoming more and more commonplace every year. However, the search engine hopes that its new tool will combat this trend. A spokesperson for the company said, “The openness and freedom that have shaped the internet as a powerful tool has come under threats from governments who want to control that technology.” By giving users access to censorship numbers, Google allows them to witness the amount of Internet censorship that they are subject to in their everyday lives. As censorship increases, many predict that citizen outrage will increase as well. The future of Internet censorship may be unsure, but for now, at least, the numbers are visible to all (Sutter, 2010).

1Cohen, “The Wiki-Way to the Nomination.”

2Hindman, 4.

References

Cohen, Noam. “The Wiki-Way to the Nomination,” New York Times, June 8, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/08/weekinreview/08cohen.html.

Hindman, Matthew. The Myth of Digital Democracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), 4.

Organizing for America, BarackObama.com, “Be the First to Know,” Organizing for America, http://my.barackobama.com/page/s/firsttoknow.

Williams, Eliza. “The Story Behind Obama’s Digital Campaign,” Creative Review, July 1, 2009, http://www.creativereview.co.uk/cr-blog/2009/june/the-story-behind-obamas-digital-campaign.

The use of online tools to engage citizens in civic and government action.