5.1 An Introduction to Political Economic Issues

The Propaganda Model

Following Smythe’s exposition of the audience and Jurgen Habermas’s (1991) elucidation of mass media as providing an apparatus whereby elite sectors of society can transform the democratising potential of the public sphere, a series of leftist academic media scholars have attempted to delineate the precise methods by which the mass media operates as a distorting lens which represents the vested interests of economic elites.

Most prominent within this PE-centred approach has been the ‘propaganda model’ (PM) of mass media presented by Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman in Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of Mass Media (1988). Chomsky and Herman begin by proclaiming that

The mass media serve as a system for communicating messages and symbols to the general populace. It is their function to amuse, entertain, and inform, and to inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behaviour that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society. In a world of concentrated wealth and major conflicts of class interest, to fulfil this role requires systematic propaganda (Chomsky and Herman,1988:1).

As such Chomsky and Herman operate within the tradition of Marxist critique of mass media as ideological propaganda whose purpose is not to inform rational critical societal debate, but to naturalise the ideology of the ruling classes. Chomsky and Herman go beyond Habermas, Adorno and Horkheimer, however, in delineating what they see as a series of structural filters through which ‘the powerful are able to fix the premise of discourse, to decide what the general populace is allowed to see hear and think about.’ (1988:1)

The five filters proposed by Chomsky and Herman are:

- The size and ownership of mass media corporations;

- The economic model predicated on generating revenue via corporate advertising;

- The reliance on ‘trusted sources’ which frequently means using government or corporate spokespeople who spend vast sums on public relations and lobbying;

- The ability of financially or politically privileged actors to provide flak, negative responses to critical media coverage; and

- An ideological filter described as anticommunism (due to Manufacturing Consent being published during the final years of the Cold war).

Subsequent writings on the PM such as Boyd-Barrett (2004) suggest that there still exists an ideological filter in the mass media, with the war on terror having largely taken the place of anticommunism and Klaehn (2009) suggesting that this filter can be rebranded as ‘the dominant ideology’. While the PM was designed with specific reference to media in the USA, subsequent studies such as Sparks (2007) suggest that with minor modifications the PM can be adapted for use with European style mass media systems which include a public service broadcaster element alongside a commercial media.

The series of filters provided in the PM continue the tradition of leftist critique of mass media following the likes of Adorno and Habermas, but significantly extend the form of critique by presenting concrete factors which, it is proposed, serve to structurally produce a system which is economically and ideologically bound to support positions of privileged and powerful elites within contemporary social formations. While critiques of the PM such as Schlesinger (1989) contend that the PM presents an overly determinate account of media systems allied with a functionalist concept of ideology, Chomsky and Herman do not claim that the PM captures all factors which influence mass media coverage of news stories, or that the filters preclude significant differentiations within and between media conglomerates, particularly noting that there are short periods where specific historic and/or social circumstances open limited windows of opportunity for journalists to engage in less constrained critiques of powerful actors. As such the PM presents media as a dynamic system dependent on a vast number of variables which constantly works to reassert hegemony, a point emphasised in Herman (1996). However, the PM does argue that while dissent is not completely suppressed, the effect of the mass media is broadly to frame events from the perspective of powerful economic and political actors. As Klaehn (2009:46) contends, the strength of the PM is the way in which it ‘highlights how ideology, communicative power and media texts link to social organization, cultural education and pervasive social, political and economic inequalities.’

Unlike the approaches of the Frankfurt School and Habermas, the progenitors of the PM do not contend that the consequences of mediated communication are inherently antidemocratic or anti-enlightenment, merely that the currently existing mass media are predicated on infrastructure which tends to produce systematic bias in favour of powerful political and economic actors. Chomsky and Herman consequently argue, both in Manufacturing Consent and elsewhere that alternative modes of media provide the potential for enhancing social awareness and social justice, albeit alongside the caveat that ‘Although the new technologies have great potential for democratic communication, there is little reason to expect the Internet to serve democratic ends if it is left to the market’ (Herman 2000).

Where the PM, and indeed political economy centred approaches in general are more broadly criticised, is that their structural approaches to the ways in which mass media is produced, or by which dominant discourses are encoded into these texts, the focus on production tends to obscure the diverse range of responses to these texts, the way that audiences decode the information. Alternative approaches, which concentrate on the processes by which audiences create meaning from media texts can be found in reception studies, audience studies and strands of cultural studies. It should, however, be noted that rather than being portrayed as oppositional approaches which take a mutually exclusive top down/bottom up or production/consumption centric ways of exploring media, PE and audience research can more productively be understood as complimentary modes of exploring media systems, which provide different modes of insight which are best understood alongside rather than in competition with one another.

Political Economies of Digital Media

PE led approaches to the study of digital media again fall into several distinct areas which approach the production of digital media from disparate areas. While Marxist approaches are again often central, there exist an additional series of approaches which consider the ways in which production of digital media, and of digital commodities in general depart in certain respects from other modes of information access and distribution.

Some of the early approaches to new/digital media focused upon the ways that the increasingly widespread distribution of networked computers afforded a mode of access which was a radical departure. Previously media had been dominated by broadcast technologies and mass media generally, whereby a very small volume of individuals were entrenched within a privileged position as content creators, and were able to broadcast mediated content from centres out to the millions of citizens who could only receive media. Mass media, then can be understood as both a one-to-many model of communication as well as a one way model, as only those who work in broadcasting can produce media, whilst the vast majority of citizens can only receive information. Such a one-to-many system of communications corresponds to the model of a centralised network.

By contrast, the Internet heralded the arrival of an alternative model, in which any network user was able to connect to any other network user(s), and was able to both send and receive mediated communications. Rather than being a one-to-many mode of communication, the Internet allowed one-to-one, one-to-many and many-to-many forms of discourse, taking the form of a distributed network. Additionally the hierarchical restrictions to access had seemingly tumbled down, with any citizen who possessed a computer, modem and internet connection able to produce mediated content. This led to a wave of early Internet scholarship which saw the Internet as a technology which contained a vast democratising potential, realising some of the formal elements discussed by socialist theorists of media such as Bertold Brecht (1932) and Hans-Magnus Enzensburger (1970) as necessary preconditions for the formation of a democratic and participatory media and culture, negating the criticisms made by Jurgen Habermas (1991) which posit the media as a fundamentally anti-democratic mode of communication which turned active citizens into passive consumers.

Whereas mass media representation reinforced and re-inscribed the structures of representative democracies, whereby an economic and political elite who have access to the means of media production and distribution are able to disproportionately influence the majority of the populace by means of their wealth (of both power and capital), networked electronic media allegedly creates structures predicated upon non-hierarchical interactions.

Such claims have been tempered, however, by the realisation that while contemporary media technologies have greatly increased the ability of certain previously marginalised groups to effectively communicate their concerns and participate in mediated discourse, the material reality of information technology commodities within the network society, has not seen social inequalities diminish and democratic participation increase. The digital divide exists as one of many divides between the haves and have-nots in contemporary society alongside divisions in wealth, education, health care, and technical expertise. Expecting the introduction of digital communications platforms to enact a process whereby these inequalities simply dissipate in the face of the deterministic properties of new technology is a utopian fantasy. As Espen Aarseth (1997:67) reminds us:

The belief that new (and ever more complex) technologies are in and of themselves democratic is not only false but dangerous. New technology creates new opportunities, but there is no reason to believe that the increased complexity of our technological lives works toward increased equality for all subjected to the technology.

Indeed, one line of pertinent criticism comes from simply observing the economic modus operandi of the world’s most popular Websites. Using Alexa’s traffic rankings, the 10 most popular Websites in 2013 are: Google, Facebook, Youtube, Yahoo, Baidu, Wikipedia, QQ.com, Linkedin, Live.com and Twitter. Aside from Wikipedia, the online encyclopaedia which is managed by the Wikimedia foundation and is a not for profit entity, every other site on the list is a profit making privately owned entity, most of whom generate funds through selling targeted advertising space. The corporations which own these Websites, such as Google (Google and Youtube), Microsoft (Live.com), Tencent (QQ.com) and Facebook are all multibillion dollar private companies, whose economic model is underpinned through a similar mechanism of selling the attentive capacities of audiences to advertisers as was the case with mass media.

There has, however, been a significant change in the ways that the adverts in question can be tailored to specific demographics. Media advertising has always been targeted in a sense, for example the producers of a commodity largely aimed at children could in the 1980s opt to buy advertising time on Saturday morning television shows which were aimed primarily at children, as while the overall audience would be lower than a prime time evening slot, the proportion of their target market would be higher. The degree to which social media can be targeted at exceptionally specific demographics, however, far surpasses the broad brush stroke approaches which were capable with mass media. Using Google’s AdWords, an advertiser can choose to have their advertisements only appear to individuals searching for specific terms such as ‘wedding photographer’ within a 20 kilometre radius of Wellington. Alternatively using Facebook, the same individual could again choose to advertise only to people within specific geographical parameters, but could narrow their market by only appearing to users whose relationship status notes that they are engaged.

The ability to present such narrowly targeted advertising is predicated upon the collation of data from a variety of sources, including both user provided data (such as profile information and statuses on a Facebook page, the search history of a particular Google account, or the contents of specific emails), and machine generated data such as cookies and an IP address. What is notable, is that the ‘work’ associated with the audience commodity has been transformed from simply viewing and listening to advertising content, to actively providing a huge amount of personal data which is then used to generate highly targeted advertising material. Far from presenting a radical break from previous modes of media, the PE of networked digital media frequently demonstrates a continuation and intensification of the work of the audience as a commodity within a media system dominated by multi-billion dollar corporations. Reviewing the propaganda model 20 years after it had initially been proposed, Herman and Chomsky (2008) point out that media concentration is both more globalised and more concentrated in 2008 than it had been in 1988.

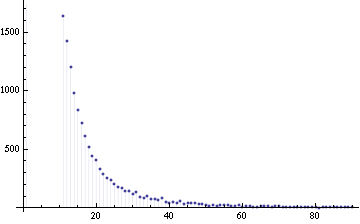

A second line of critique levelled at the notion that digital networked technologies and the Internet would bring about democratising changes to communications comes from the work of Alberto Barabasi and Reka Albert, whose work studies the topological form of various forms of complex network, including the World Wide Web as one key example. What Barabasi and Albert discovered was that across a range of different networks which shared the same form, a power law distribution described the connectivity of the network. In contrast to a normal distribution, which has the shape of a bell curve, with equal distributions either side of the mean, a power law is a distribution in which there are a handful of points for which there are extremely high values, and a very large number of points for which there are exceptionally low values, the latter of which is often described as a long tail.

Additionally, Barabasi and Albert posit a method by which the connectivity of websites grow, which they termed preferential attachment. Effectively, this suggests that new nodes tend to connect to nodes which are already established as popular, which further entrenches the popularity of the pre-existing websites, which leads to these sites becoming hugely popular over time, whereas the vast majority of websites remain virtually invisible to the vast majority of web users. Surmising these findings, Barabasi comments that:

the most intriguing result of our Web mapping project was the complete absence of democracy, fairness and egalitarian values on the Web. We learned that the topology of the Web prevents us from seeing anything but a mere handful of the billion documents out there’ (Barabasi 2003:56/57).

Commons and P2P Production

This post outlines several modes of commons – types of asset which are held in collective or communal ownership rather than as private commodities owned by individuals or individual corporations.

The first mode of commons I’d like to discuss is the model of common land – what we could think of as a pre-industrial mode of commons, albeit one which still exists today through our shared ownership and access to things like air. Land which was accessible for commoners to graze cattle or sheep, or to collect firewood or cut turf for fuel. Anyone had access to this communal resource and there was no formal hierarchical management of the common land – no manager or boss who ensured that no one took too much wood or had too many sheep grazing on the land (although there did exist arable commons where lots were allocated on an annual basis). So access and ownership of this communal resource was distributed, management was horizontal rather than hierarchical, but access effectively depended upon geographical proximity to the site in question.

A second mode of commons is that of the public service, which we could conceptualise as an industrial model of commonwealth. For example consider the example of the National Health Service in the UK: unlike common land, this was a public service designed to operate on a national scale, for the common good of the approximately 50 million inhabitants of the UK. In order to manage such a large scale, industrial operation, logic dictated that a strict chain of managerial hierarchy be established to run and maintain the health service – simply leaving the British population to self-organise the health service would undoubtedly have been disastrous.

This appear to be a case which supports the logic later espoused by Garret Hardin in his famed 1968 essay “The Tragedy of the Commons,” whereby Hardin, an American ecologist forcefully argued that the model of the commons could only be successful in relatively small-scale endeavours, and that within industrial society this would inevitably lead to ruin, as individuals sought to maximise their own benefit, whilst overburdening the communal resource. Interestingly, Hardin’s central concern was actually overpopulation, and he argued in the essay that ‘The only way we can preserve and nurture other, more precious freedoms, is by relinquishing the freedom to breed.’ Years later he would suggest that it was morally wrong to give aid to famine victims in Ethiopia as this simply encouraged overpopulation.

More recent developments, however, have shown quite conclusively that Hardin was wrong: the model of the commons is not doomed to failure in large-scale projects. In part this is due to the fact that Hardin’s model of the commons was predicated on a complete absence of rules – it was not a communally managed asset, but a free-for-all, and partially this can be understood as a result of the evolution of information processing technologies which have revolutionised the ways in which distributed access, project management and self-organisation can occur. This contemporary mode of the commons, described by Yochai Benler (2006) and others as commons-led peer production, or by other proponents simply as peer-to-peer(P2P) resembles aspects of the distributed and horizontal access characteristic of pre-modern commons, but allows access to these projects on a non-local scale.

Emblematic of P2P process has been the Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) and Creative Commons movement (this textbook being an example of the latter). FOSS projects often include thousands of workers who cooperate on making a piece of software which is then made readily available as a form of digital commons, unlike proprietary software which seeks to reduce access to a good whose cost of reproduction is effectively zero. In addition to the software itself, the source code of the program is made available, crucially meaning that others can examine, explore, alter and improve upon existing versions of FOSS. Popular examples of FOSS include WordPress – which is now used to create most new websites (including this one!) as it allows users with little technical coding ability to create complex and stylish participatory websites – the web browsers Firefox and Chrome, and the combination of Apache (web server software) and Linux (operating system) which together form the back end for most of the servers which host World Wide Web content.

What is really interesting, is that in each of these cases, a commons-led approach has been able to economically out-compete proprietary alternatives – which in each case have had huge sums of money invested into them. The prevailing economic logic throughout industrial culture – that hierarchically organised private companies were most effective and efficient at generating reliable and functional goods was shown to be wrong. A further example which highlights this is Wikipedia, the online open-access encyclopaedia which according to research is not only the largest repository of encyclopaedic knowledge, but for scientific and mathematical subjects is the most detailed and accurate. Had you said 15 years ago that a disparate group of individuals who freely cooperated in their free time over the Internet and evolved community guidelines for moderating content which anyone could alter, would be able to create a more accurate and detailed informational resource than a well-funded established professional company (say Encyclopaedia Britannica) most economists would have laughed. But again, the ability of people to self-organise over the Internet based on their own understanding of their interests and competencies has been shown to be a tremendously powerful way of organising.

Of course there are various attempts to integrate this type of crowd-sourced P2P model into new forms of capitalism – it would be foolish to think that powerful economic actors would simply ignore the hyper-productive aspects of P2P. But for people interested in commons and alternative ways of organising, a lot can be taken from the successes of FOSS and creative commons.

Now where some this gets really interesting, is in the current moves towards Open Source Hardware (OSH), what is sometimes referred to as maker culture, where we move from simply talking about software, or digital content which can be entirely shared over telecommunications networks. OSH is where the design information for various kinds of device are shared. Key amongst these are 3D printers, things like RepRap, an OSH project to design a machine allowing individuals to print their own 3D objects. Users simply download 3D Computer-Assisted-Design (CAD) files, which they can then customise if they wish, before hitting a print button – just as they would print a word document, but the information is sent to a 3D rather than 2D printer. Rather than relying on a complex globalised network whereby manufacturing largely occurs in China, this empowers people to start making a great deal of things themselves. It reduces reliance on big companies to provide the products that people require in day-to-day life and so presents a glimpse of a nascent future in which most things are made locally, using a freely available design commons. Rather than relying on economies of scale, this postulates a system of self-production which could offer a functional alternative which would have notable positive social and ecological ramifications.

Under the current economic situation though, people who contribute to these communities alongside other forms of commons are often not rewarded for the work they put into things, and so have to sell their labor power elsewhere in order to make ends meet financially. Indeed, this isn’t new, capitalism has always been especially bad at remunerating people who do various kinds of work which is absolutely crucial the the functioning of a society – with domestic work and raising children being the prime example. So the question is, how could this be changed so as to reward people for contributing to cultural, digital and other forms of commons?

One possible answer which has attracted a lot of commentary is the notion of a universal basic income. Here the idea is that as all citizens are understood to actively contribute to society via their participation in the commons, everyone should receive sufficient income to subsist – to pay rent, bills, feed themselves and their dependants, alongside having access to education, health care and some form of information technology. This basic income could be supplemented through additional work – and it is likely that most people would choose to do this (not many people enjoy scraping by with the bare minimum) – however, if individuals wanted to focus on assisting sick relatives, contributing to FOSS projects or helping out at a local food growing cooperative they would be empowered to do so without the fear of financial ruin. As an idea it’s something that has attracted interest and support from a spectrum including post-Marxists such as Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (2017) through to liberals such as the British Green Party [see also NZ Green Party work and employment policy].

For more details on P2P check out the Peer to Peer Foundation which hosts a broad array of excellent articles on the subject.

Political Ecologies of Media

At the outset of this chapter, we defined political economy as the study of production, and subsequently considered what it means to study the production of media. Then we looked at how production reveals a set of political relationships which are far from ideologically neutral by looking at a range of issues pertaining to ownership, intellectual property, relationships to government, and funding mechanism. This was especially via advertising, and we considered in some detail how these factors can be understood to influence the content and messages commonly encountered within media texts. However, understanding the production of media and the political issues which arise from media to be limited to the ways in which meanings are generated by the texts which can be thought of as the outputs of media, neglects what could be considered a range of ethical and political issues which relate to the production, consumption and disposal of the technologies which are necessary for media systems to function.

Considering issues which arise from the design, production and sustainability of hardware systems has traditionally been considered outside the bounds of media studies as a discipline, which situated within the humanities has been focussed upon the cultural impacts of symbols and messages, rather than exploring the ethics of mining the metals and minerals needed to make cameras and computers, tablets and telephones. Indeed, early approaches to media and ecology explicitly stated that their goal was:

To make people more conscious of the fact that human beings live in two different kinds of environments. One is the natural environment and consists of things like air, trees, rivers, and caterpillars. The other is the media environment, which consists of language, numbers, images, holograms, and all of the other symbols, techniques, and machinery that make us what we are (Postman, 2000:11).

This type of thought can be understood as dualistic; it reinforces the notion that there are binary oppositions between nature and culture, discourse and materiality, the sciences and the humanities. Dualistic modes of thought can be understood as holding a privileged place within the canon of Western philosophy, whereby the divisions between man and God, nature and culture, immanence and transcendence, and body and soul were pivotal to the religious doctrines which organised modes of life for centuries.

In contrast to this type of approach, there has been a contemporary drive within elements of media studies scholarship to move towards a disciplinary approach which highlights the interconnectedness of nature and culture, technology and expression, science and art. This move towards expanding the scope of political economy to include the social and environmental impacts of technologies of mediation can be understood as being closely related to the approach found within political ecology, which Paul Robbins (2004:12) defines as follows:

Political ecology seeks to expose flaws in dominant approaches to the environment favoured by corporate, state, and international authorities, working to demonstrate the undesirable impacts of policies and market conditions, especially from the point of view of local people, marginal groups, and vulnerable populations. It works to “denaturalise” certain social and environmental conditions, showing them to be the contingent outcomes of power, and not inevitable. As critical historiography, deconstruction and myth-busting research, political ecology is a hatchet, cutting and pruning away the stories, methods and policies that create pernicious social and environmental outcomes

Political ecology then strives to break down the perceived barriers between nature and culture, demonstrating through detailed analyses the ways in which human relations and politically conditioned activities affect and impact upon the environment, which in turn conditions our understandings of nature. Unlike the approach espoused by Neil Postman, a political ecology of media does not seek to separate media systems from the “natural” environment, it seeks to explore the multiplicity of ways in which media condition our preconceptions of what nature is, whilst simultaneously exploring how media production and consumption produces material impacts upon ecosystems and social systems.

Consequently, there have been a range of attempts made within the past few years to begin addressing what some of the social and ecological issues associated with the life cycle of media hardware are, and to explore some of the ways that these issues are being addressed by a disparate range of groups. According to this perspective:

Media and communication scholars have had no problem in the past dealing with a range of critical insights to other ethical problems, including those related to social harms (violence), cultural harms (prejudicial stereotypes), economic harms (ownership), or political harms (propaganda)… The eco-crisis presents media studies with an eco-ethical choice: either continue to document and assess the growing consumption of media technologies without understanding their ecological context, or advocate policies and influence polities to reduce the consumption of media technologies—not an easy choice for a field hooked on iPodpeople and PCers. We think it’s time to assume intellectual responsibility for the ecological dimension of the media, and deal with difficult ethical challenges posed by the eco-crisis. (Miller and Maxwell 2008:4)

REFERENCES

Aarseth, E. J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on ergodic literature. JHU Press.

Barabási, A. L. (2003). Linked: The new science of networks.

Barabási, A. L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. science, 286(5439), 509-512.

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. Yale University Press.

Boyd-Barrett, O. (2004). Judith Miller, the New York Times, and the propaganda model. Journalism studies, 5(4), 435-449.

Brecht, B. (1932). The radio as an apparatus of communication (pp. 51-53).

Enzensberger, H. M. (1970). Constituents of a Theory of the Media. New Left Review, (64), 13.

Habermas, J., & Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. MIT press.

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243-1248.

Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2017). Assembly. Oxford University Press.

Herman, E. S. (1996). The propaganda model revisited. Monthly Review, 48(3), 115.

Herman, E. S. (2000). The propaganda model: A retrospective. Journalism Studies, 1(1), 101-112.

Herman, E., & Chomsky, Noam. (2008). Manufacturing consent : The political economy of the mass media (Anniversary ed. / with a new afterword by Edward S. Herman. ed.). London: Bodley Head.

Klaehn, J. (2009). The Propaganda Model: Theoretical and Methodological Considerations. Westminster Papers in Communication & Culture, 6(2).

Schlesinger, P. (1989). From production to propaganda?. Media, Culture & Society, 11(3), 283-306.

Sparks, C. (2007). Extending and refining the propaganda model. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 4(2).

Taffel, Sy. Escaping Attention: Digital Media Hardware, Materiality and Ecological Cost 2013.

This is one of the terms employed to describe an aggregate of receivers of media texts. These can also be described in demographic terms such as location TV channel choice or age etc. Audience commodity refers to the attentive capacities of audiences as paying consumers of media texts. See also receivers and users.

The public sphere is the area of social life where public opinion can emerge.

Research perspective which draws on the Frankfurt and Birmingham schools of thought that seeks to understand the interplay of texts and practices in everyday life. It emerges in response to criticisms of the audience as passive and of popular culture as inferior and problematic.

Media always constructs images as representations of the real.

Within media studies production is the creation of meaning.

In Economics and Political Economy, the way in which goods and services are delivered or shared among individuals and institutions. For example, television channels and movie theaters are alternate ways of distributing films, while the money earned from a film is distributed unevenly to those involved in its production.

Unique numerical label that identifies each computer on the Internet.

The idea raised by Dallas Smythe that the primary economic driver of media industries is access to audiences sold to advertisers rather than the content itself.

Media theory advanced Chomsky and Herman that suggests that mass media serve as a mechanism to amuse, entertain, and inform even as they inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behavior that will help them integrate into and help them function as members of society and its prevailing ideology.

Types of assets held in collective or communal ownership rather than as private commodities. Assets in this context does not necessarily mean tangible commodities but can include assets like internet/cyber spaces where media can be commonly shared.

A movement focused on developing computer software that is free and which allows the programming itself to be accessed and altered by users in order to develop and improve it

Use of a distributed network to communicate from one person or computer to another without the use of a centralized server.

Culture/sub-culture focused on the creation of new devices as well as tinkering with and fixing existing devices.