1.6 Mass Media and Popular Culture

Burroughs’s jubilant call to bring art “out of the closets and into the museums” spoke to postmodernism’s willingness to meld high and low culture (Leonard, 1997). And although the Postmodern Age specifically embraced popular culture, mass media and pop culture have been entwined from their very beginnings. In fact, mass media often determines what does and does not make up the pop culture scene. How to define popular culture? A useful starting point is to relate it to the concept of culture. While we defined culture earlier in this book as “the shared values, attitudes, beliefs, and practices that characterize, organize, and stabilize a social group, organization, or institution,” here the definition can be expanded, where culture provides “a means or organizing and stabilizing communal life and everyday activities through specific beliefs, rituals, rites, performances, art forms, language, clothing, food, music, dance, and other human expressive, intellectual, and communicative pursuits…..associated with a group of people at a particular period of time” (Danesi, 2018, p. 2). Danesi’s definition is more expansive, in the process embedding media and technology into the concept of culture to permit a view of popular culture that is “populist, unpredictable, and ephemeral, reflecting the ever-changing tastes of one generation after another” and created in a “open social forum” (p. 4).

Tastemakers

Historically, mass pop culture has been fostered by an active and tastemaking mass media that introduces and encourages the adoption of certain trends. Although they are similar in some ways to the widespread media gatekeepers discussed in Section 1.4.3 “Gatekeepers”, tastemakers differ in that they are most influential when the mass media is relatively small and concentrated. When only a few publications or programs reach millions of people, their writers and editors are highly influential. The New York Times’s restaurant reviews used to be able to make a restaurant successful or unsuccessful through granting (or withdrawing) its rating.

Or take the example of Ed Sullivan’s variety show, which ran from 1948 to 1971, and is most famous for hosting the first U.S. appearance of the Beatles—a television event that was at the time the most-watched TV program ever. Sullivan hosted musical acts, comedians, actors, and dancers and had the reputation of being able to turn an act on the cusp of fame into full-fledged stars. Comedian Jackie Mason compared being on The Ed Sullivan Show to “an opera singer being at the Met. Or if a guy is an architect that makes the Empire State Building.…This was the biggest (Leonard, 1997).” Sullivan was a classic example of an influential tastemaker of his time. A more modern example is Oprah Winfrey, whose book club endorsements often send literature, including old classics like Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, skyrocketing to the top of The New York Times Best Sellers list.

Along with encouraging a mass audience to see (or skip) certain movies, television shows, video games, books, or fashion trends, people use tastemaking to create demand for new products. Companies often turn to advertising firms to help create public hunger for an object that may have not even existed 6 months before. In the 1880s, when George Eastman developed the Kodak camera for personal use, photography was most practiced by professionals. “Though the Kodak was relatively cheap and easy to use, most Americans didn’t see the need for a camera; they had no sense that there was any value in visually documenting their lives,” noted New Yorker writer James Surowiecki (Surowiecki, 2003). Kodak became a wildly successful company not because Eastman was good at selling cameras, but because he understood that what he really had to sell was photography. Apple Inc. is a modern master of this technique. By leaking just enough information about a new product to cause curiosity, the technology company ensures that people will be waiting excitedly for an official release.

Tastemakers help keep culture vital by introducing the public to new ideas, music, programs, or products, but tastemakers are not immune to outside influence. In the traditional media model, large media companies set aside large advertising budgets to promote their most promising projects; tastemakers buzz about “the next big thing,” and obscure or niche works can get lost in the shuffle.

A Changing System for the Internet Age

In retrospect, the 20th century was a tastemaker’s dream. Advertisers, critics, and other cultural influencers had access to huge audiences through a number of mass-communication platforms. However, by the end of the century, the rise of cable television and the Internet had begun to make tastemaking a more complicated enterprise. While The Ed Sullivan Show regularly reached 50 million people in the 1960s, the most popular television series of 2009—American Idol—averaged around 25.5 million viewers per night, despite the fact that the 21st-century United States could claim more people and more television sets than ever before (Wikipedia, 2012). However, the proliferation of TV channels and other competing forms of entertainment meant that no one program or channel could dominate the attention of the American public as in Sullivan’s day.

| Show/Episode | Number of Viewers | Percent of Households | Year |

| The Ed Sullivan Show / The Beatles’ first appearance | 73 million | 45.1% | 1964 |

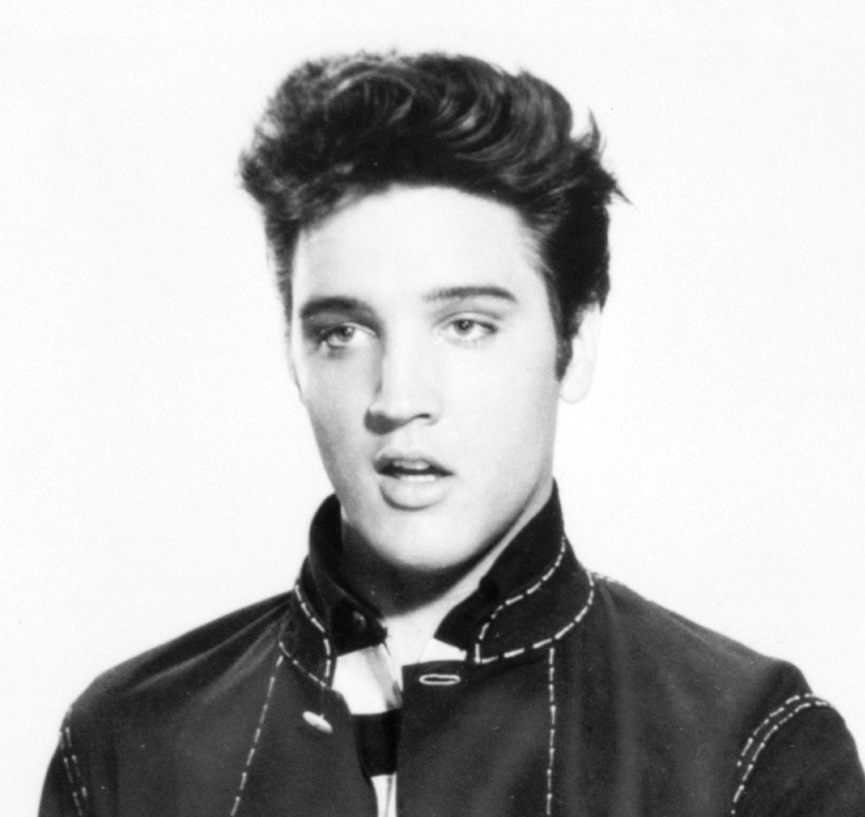

| The Ed Sullivan Show / Elvis Presley’s first appearance | 60 million | 82.6% | 1956 |

| I Love Lucy / “Lucy Goes to the Hospital” | 44 million | 71.7% | 1953 |

| M*A*S*H / Series finale | 106 million | 60.2% | 1983 |

| Seinfeld / Series finale | 76 million | 41.3% | 1998 |

| American Idol / Season 5 finale | 36 million | 17% | 2006 |

Meanwhile, a low-tech home recording of a little boy acting loopy after a visit to the dentist (“David After Dentist”) garnered more than 37 million YouTube viewings in 2009 alone. The Internet appears to be eroding some of the tastemaking power of the traditional media outlets. No longer is the traditional mass media the only dominant force in creating and promoting trends. Instead, information spreads across the globe without the active involvement of traditional mass media. Websites made by nonprofessionals can reach more people daily than a major newspaper. Music review sites such as Pitchfork keep their eyes out for the next big thing, whereas review aggregators like Rotten Tomatoes allow readers to read hundreds of movie reviews by amateurs and professionals alike. Blogs make it possible for anyone with Internet access to potentially reach an audience of millions. Some popular bloggers have transitioned from the traditional media world to the digital world, but others have become well known without formal institutional support. The celebrity-gossip chronicler Perez Hilton had no formal training in journalism when he started his blog, PerezHilton.com, in 2005; within a few years, he was reaching millions of readers a month.

E-mail and text messages allow people to transmit messages almost instantly across vast geographic expanses. Although personal communications continue to dominate, e-mail and text messages are increasingly used to directly transmit information about important news events. When Barack Obama wanted to announce his selection of Joe Biden as his vice-presidential running mate in the 2008 election, he bypassed the traditional televised press conference and instead sent the news to his supporters directly via text message—2.9 million text messages, to be exact (Covey). Social networking sites, such as Facebook, and microblogging services, such as Twitter, are another source of late-breaking information. When Michael Jackson died of cardiac arrest in 2009, “RIP Michael Jackson” was a top trending topic on Twitter before the first mainstream media first reported the news.

Thanks to these and other digital-age media, the Internet has become a pop culture force, both a source of amateur talent and a source of amateur promotion. However, traditional media outlets still maintain a large amount of control and influence over U.S. pop culture. One key indicator is the fact that many singers or writers who first make their mark on the Internet quickly transition to more traditional media—YouTube star Justin Bieber was signed by a mainstream record company, and blogger Perez Hilton is regularly featured on MTV and VH1. New-media stars are quickly absorbed into the old-media landscape.

Getting Around the Gatekeepers

Not only does the Internet give untrained individuals access to a huge audience for their art or opinions, but it also allows content creators to reach fans directly. Projects that may not have succeeded through traditional mass media may get a second chance through newer media. The profit-driven media establishment has been surprised by the success of some self-published books. For example, dozens of literary agents rejected first-time author Daniel Suarez’s novel Daemon before he decided to self-publish in 2006. Through savvy self-promotion through influential bloggers, Suarez garnered enough attention to land a contract with a major publishing house.

Suarez’s story, though certainly exceptional, reaches some of the questions facing creators and consumers of pop culture in the Internet age. Without the influence of an agent, editor, or PR company, self-published content may be able to hew closer to the creator’s intention. However, much of the detailed marketing work must be performed by the work’s creator instead of by a specialized public relations team. And with so many self-published, self-promoted works uploaded to the Internet every day, it’s easy for things—even good things—to get lost in the shuffle.

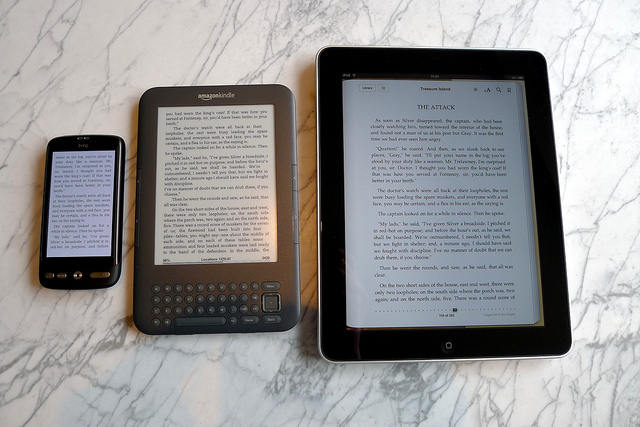

Critic Laura Miller spells out some of the ways in which writers in particular can take control of their own publishing: “Writers can upload their works to services run by Amazon, Apple and… Barnes & Noble, transforming them into e-books that are instantly available in high-profile online stores. Or they can post them on services like Urbis.com, Quillp.com, or CompletelyNovel.com and coax reviews from other hopeful users (Miller, 2010).” Miller also points out that many of these companies can produce hard copies of books as well. While such a system may be a boon for writers who haven’t had success with the traditional media establishment, Miller notes that it may not be the best option for readers, who “rarely complain that there isn’t enough of a selection on Amazon or in their local superstore; they’re more likely to ask for help in narrowing down their choices (Miller, 2010).”

The question remains: Will the Internet era be marked by a huge and diffuse pop culture, where the power of traditional mass media declines and, along with it, the power of the universalizing blockbuster hit? Or will the Internet create a new set of tastemakers—influential bloggers—or even serve as a platform for the old tastemakers to take on new forms?

Democratizing Tastemaking

In 1993, The New York Times restaurant critic Ruth Reichl wrote a review about her experiences at the upscale Manhattan restaurant Le Cirque. She detailed the poor service she received when the restaurant staff did not know her and the excellent service she received when they realized she was a professional food critic. Her article illustrated how the power to publish reviews could affect a person’s experience at a restaurant. The Internet, which turned everyone with the time and interest into a potential reviewer, allowed those ordinary people to have their voices heard. In the mid-2000s, websites such as Yelp and TripAdvisor boasted hundreds of reviews of restaurants, hotels, and salons provided by users. Amazon allows users to review any product it sells, from textbooks to bathing suits. The era of the democratized review had come, and tastemaking was now everyone’s job.

By crowdsourcing (harnessing the efforts of a number of individuals online to solve a problem) the review process, the idea was, these sites would arrive at a more accurate description of the service in choice. One powerful reviewer would no longer be able to wield disproportionate power; instead, the wisdom of the crowd would make or break restaurants, movies, and everything else. Anyone who felt treated badly or scammed now had recourse to tell the world about it. By 2008, Yelp had 4 million reviews

However, mass tastemaking isn’t as perfect as some people had promised. Certain reviewers can overly influence a product’s overall rating by contributing multiple votes. One study found that a handful of Amazon users were casting hundreds of votes, while most rarely wrote reviews at all. Online reviews also tend to skew to extremes—more reviews are written by the ecstatic and the furious, while the moderately pleased aren’t riled up enough to post online about their experiences. And while traditional critics are supposed to adhere to ethical standards, there’s no such standard for online reviews. Savvy authors or restaurant owners have been known to slyly insert positive reviews or attempt to skew ratings systems. To get an accurate picture, potential buyers may find themselves wading through 20 or 30 online reviews, most of them from nonprofessionals. And sometimes those people aren’t professionals for a reason. Consider these user reviews on Amazon of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “There is really no point and it’s really long,” “I really didn’t enjoy reading this book and I wish that our English teacher wouldn’t force my class to read this play,” and “don’t know what Willy Shakespeare was thinking when he wrote this one play tragedy, but I thought this sure was boring! Hamlet does too much talking and not enough stuff.” While some may argue that these are valid criticisms of the play, these comments are certainly a far cry from the thoughtful critique of a professional literary critic.

These and other issues underscore the point of having reviews in the first place—that it’s an advantage to have certain places, products, or ideas examined and critiqued by a trusted and knowledgeable source. In an article about Yelp, The New York Times noted that one of the site’s elite reviewers had racked up more than 300 reviews in 3 years, and then pointed out that “By contrast, a New York Times restaurant critic might take six years to amass 300 reviews. The critic visits a restaurant several times, strives for anonymity and tries to sample every dish on the menu (McNeil, 2008).” Whatever your vantage point, it’s clear that old-style tastemaking is still around and still valuable—but the democratic review is here to stay.

References

Covey, Nic. “Flying Fingers,” Nielsen, http://en-us.nielsen.com/main/insights/consumer_insight/issue_12/flying_fingers.

Danesi, Marcel. Popular Culture: Introductory Perspectives. Rowman & Littlefield.

Leonard, John. “The Ed Sullivan Age,” American Heritage, May/June 1997.

McNeil, Donald G. “Eat and Tell,” New York Times, November 4, 2008, Dining & Wine section.

Miller, Laura. “When Anyone Can Be a Published Author,” Salon, June 22, 2010, http://www.salon.com/books/laura_miller/2010/06/22/slush.

Surowiecki, James. “The Tastemakers,” New Yorker, January 13, 2003.

Wikipedia, , s.v. “The Ed Sullivan Show,” last modified June 26, 2012, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ed_Sullivan_Show; Wikipedia, s.v. “American Idol,” last modified June 26, 2012, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Idol.

Thought of as the culture of the masses or mass audience. However, this does not mean pop culture is common across all cultures, but rather it reflects its audiences and users. Different schools of thought have approached popular culture differently. For example, members of the Frankfurt School saw popular culture as trivial and commercial and something to be concerned with, while members of the Birmingham School recognized that how we interact popular culture matters greatly.

In early media theory the idea that mass produced culture was consumed by an audience who was large, undifferentiated, likely uniformed, and largely passive. As media theory has developed, audiences are seen as considerably more nuanced and active.