1.4 Convergence

It’s important to keep in mind that the implementation of new technologies doesn’t mean that the old ones simply vanish into dusty museums. Today’s media consumers still watch television, listen to radio, read newspapers, and become immersed in movies. The difference is that it’s now possible to do all those things through one device—be it a personal computer or a smartphone—and through the Internet. Such actions are enabled by media convergence, the process by which previously distinct technologies come to share tasks and resources.

Convergence Culture

The term convergence can hold several different meanings. In his book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, Henry Jenkins offers a useful definition of convergence as it applies to new media:

“By convergence, I mean the flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between multiple media industries, and the migratory behavior of media audiences who will go almost anywhere in search of the kinds of entertainment experiences they want (Jenkins, 2006).”

A self-produced video on YouTube that gains enormous popularity and thus receives the attention of a news outlet is a good example of this migration of both content and audiences. Consider this flow: The video appears and gains notoriety, so a news outlet broadcasts a story about the video, which in turn increases its popularity on YouTube. This migration works in a number of ways. Humorous or poignant excerpts from television or radio broadcasts are often posted on social media sites and blogs, where they gain popularity and are seen by more people than had seen the original broadcast.

Thanks to new media, consumers now view all types of media as participatory. For example, the massively popular talent show American Idol combines an older-media format—television—with modern media consumption patterns by allowing the home audience to vote for a favorite contestant. However, American Idol segments regularly appear on YouTube and other websites, where people who may never have seen the show comment on and dissect them. Phone companies report a regular increase in phone traffic following the show, presumably caused by viewers calling in to cast their votes or simply to discuss the program with friends and family. As a result, more people are exposed to the themes, principles, and culture of American Idol than the number of people who actually watch the show (Jenkins, 2006).

New media have encouraged greater personal participation in media as a whole. Although the long-term cultural consequences of this shift cannot yet be assessed, the development is undeniably a novel one. As audiences become more adept at navigating media, this trend will undoubtedly increase.

Bert Is Evil

In 2001, high school student Dino Ignacio created a collage of Sesame Street character Bert with terrorist Osama bin Laden as part of a series for his website. Called “Bert Is Evil,” the series featured the puppet engaged in a variety of illicit activities. A Bangladesh-based publisher looking for images of bin Laden found the collage on the Internet and used it in an anti-American protest poster, presumably without knowledge of who Bert was. This ended up in a CNN report on anti-American protests, and public outrage over the use of Bert made Ignacio’s original site a much-imitated cult phenomenon.

The voyage of this collage from a high school student’s website to an anti-American protest poster in the Middle East to a cable television news network and finally back to the Internet provides a good illustration of the ways in which content migrates across media platforms in the modern era. As the collage crossed geographic and cultural boundaries, it grew on both corporate and grassroots media. While this is not the norm for media content, the fact that such a phenomenon is possible illustrates the new directions in which media is headed (Jenkins, 2006).

A cell phone that also takes pictures and video is an example of the convergence of digital photography, digital video, and cellular telephone technologies. An extreme, and currently nonexistent, example of technological convergence would be the so-called black box, which would combine all the functions of previously distinct technology and would be the device through which we’d receive all our news, information, entertainment, and social interaction.

Kinds of Convergence

But convergence isn’t just limited to technology. Media theorist Henry Jenkins argues that convergence isn’t an end result (as is the hypothetical black box), but instead a process that changes how media is both consumed and produced. Jenkins breaks convergence down into five categories:

- Economic convergence occurs when a company controls several products or services within the same industry. For example, in the entertainment industry a single company may have interests across many kinds of media. For example, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation is involved in book publishing (HarperCollins), newspapers (New York Post, The Wall Street Journal), sports (Colorado Rockies), broadcast television (Fox), cable television (FX, National Geographic Channel), film (20th Century Fox), Internet (MySpace), and many other media.

- Organic convergence is what happens when someone is watching a television show online while exchanging text messages with a friend and also listening to music in the background—the “natural” outcome of a diverse media world.

- Cultural convergence has several aspects. Stories flowing across several kinds of media platforms is one component—for example, novels that become television series (True Blood); radio dramas that become comic strips (The Shadow); even amusement park rides that become film franchises (Pirates of the Caribbean). The character Harry Potter exists in books, films, toys, and amusement park rides. Another aspect of cultural convergence is participatory culture—that is, the way media consumers are able to annotate, comment on, remix, and otherwise influence culture in unprecedented ways. The video-sharing website YouTube is a prime example of participatory culture. YouTube gives anyone with a video camera and an Internet connection the opportunity to communicate with people around the world and create and shape cultural trends.

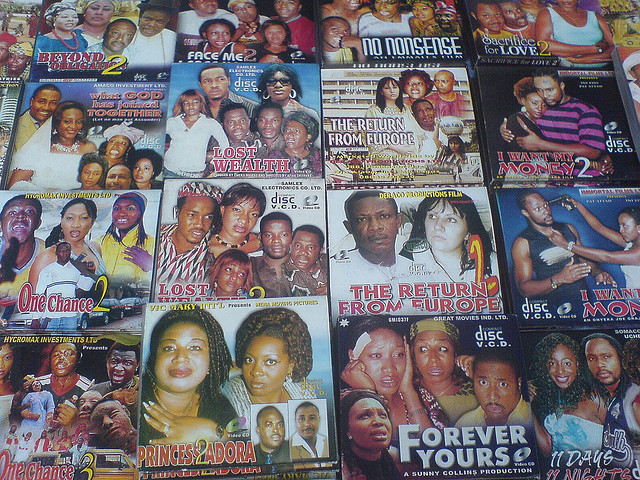

- Global convergence is the process of geographically distant cultures influencing one another despite the distance that physically separates them. Nigeria’s cinema industry, nicknamed Nollywood, takes its cues from India’s Bollywood, which is in turn inspired by Hollywood in the United States. Tom and Jerry cartoons are popular on Arab satellite television channels. Successful American horror movies The Ring and The Grudge are remakes of Japanese hits. The advantage of global convergence is access to a wealth of cultural influence; its downside, some critics posit, is the threat of cultural imperialism, defined by Herbert Schiller as the way developing countries are “attracted, pressured, forced, and sometimes bribed into shaping social institutions to correspond to, or even promote, the values and structures of the dominating centre of the system” (White, 2001).” Cultural imperialism, as a key part of the process of globalization, can be a formal policy or can happen more subtly, as with the spread of outside influence through television, movies, and other cultural projects.

- Technological convergence is the merging of technologies such as the ability to watch TV shows online on sites like Hulu or to play video games on mobile phones like the Apple iPhone. When more and more different kinds of media are transformed into digital content, as Jenkins notes, “we expand the potential relationships between them and enable them to flow across platforms (Jenkins, 2001).”

Effects of Convergence

Jenkins’s concept of organic convergence is perhaps the most telling. To many people, especially those who grew up in a world dominated by so-called old (or “legacy”) media, there is nothing organic about today’s media-dominated world. As a New York Times editorial recently opined, “Few objects on the planet are farther removed from nature—less, say, like a rock or an insect—than a glass and stainless steel smartphone (New York Times, 2010).” But modern American culture is plugged in as never before, and today’s high school students have never known a world where the Internet didn’t exist. Such a cultural sea change causes a significant generation gap between those who grew up with new media and those who didn’t.

A 2010 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that Americans aged 8 to 18 spent more than 7.5 hours with electronic devices each day—and, thanks to multitasking, they packed an average of 11 hours of media content into that 7.5 hours (Lewin, 2010). More recent data suggests that 95% of teens report they have access to a smartphone, and 45% of teens claim they are online almost constantly (Anderson & Jiang, 2018). These statistics highlight some of the aspects of the new digital model of media consumption: participation and multitasking. Today’s teenagers aren’t passively sitting in front of screens, quietly absorbing information. Instead, they are sending text messages to friends, linking news articles on Facebook, commenting on YouTube videos, writing reviews of television episodes to post online, and generally engaging with the culture they consume. Convergence has also made multitasking much easier, as many devices allow users to surf the Internet, listen to music, watch videos, play games, and reply to e-mails on the same machine. It is important to note that high media use is not solely a function of age, even if the type of media use is different: A recent Pew Research article reveals that adults 60 and over spend more than half of their daily leisure time, four hours and 16 minutes, in front of screens, mostly watching TV or videos. Screen time has increased for those in their 60s, 70s, 80s and beyond, and the rise is apparent across genders and education levels. Meanwhile, the time that these older adults spend on other recreational activities, such as reading or socializing, has ticked down (Livingstone, 2019, para 2)

However, it’s still difficult to predict how media convergence and immersion are affecting culture, society, and individual brains. In his 2005 book Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that today’s television and video games are mentally stimulating, in that they pose a cognitive challenge and invite active engagement and problem solving. Poking fun at alarmists who see every new technology as making children stupider, Johnson jokingly cautions readers against the dangers of book reading: It “chronically understimulates the senses” and is “tragically isolating.” Even worse, books “follow a fixed linear path. You can’t control their narratives in any fashion—you simply sit back and have the story dictated to you…. This risks instilling a general passivity in our children, making them feel as though they’re powerless to change their circumstances. Reading is not an active, participatory process; it’s a submissive one (Johnson, 2005).”

A 2010 book by Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains is more pessimistic. Carr worries that the vast array of interlinked information available through the Internet is eroding attention spans and making contemporary minds distracted and less capable of deep, thoughtful engagement with complex ideas and arguments. “Once I was a scuba diver in a sea of words,” Carr reflects ruefully. “Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski (Carr, 2010).” Carr cites neuroscience studies showing that when people try to do two things at once, they give less attention to each and perform the tasks less carefully. In other words, multitasking makes us do a greater number of things poorly. Whatever the ultimate cognitive, social, or technological results, convergence is changing the way we relate to media today.

Video Killed the Radio Star: Convergence Kills Off Obsolete Technology—or Does It?

When was the last time you used a rotary phone? How about a street-side pay phone? Or a library’s card catalog? When you need brief, factual information, when was the last time you reached for a volume of Encyclopedia Britannica? Odds are it’s been a while. All of these habits, formerly common parts of daily life, have been rendered essentially obsolete through the progression of convergence.

But convergence hasn’t erased old technologies; instead, it may have just altered the way we use them. Take cassette tapes and Polaroid film, for example. Influential musician Thurston Moore of the band Sonic Youth recently claimed that he only listens to music on cassette. Polaroid Corporation, creators of the once-popular instant-film cameras, was driven out of business by digital photography in 2008, only to be revived 2 years later—with pop star Lady Gaga as the brand’s creative director. Several Apple iPhone apps allow users to apply effects to photos to make them look more like a Polaroid photo.

Cassettes, Polaroid cameras, and other seemingly obsolete technologies have been able to thrive—albeit in niche markets—both despite and because of Internet culture. Instead of being slick and digitized, cassette tapes and Polaroid photos are physical objects that are made more accessible and more human, according to enthusiasts, because of their flaws. “I think there’s a group of people—fans and artists alike—out there to whom music is more than just a file on your computer, more than just a folder of MP3s,” says Brad Rose, founder of a Tulsa, Oklahoma-based cassette label (Hogan, 2010). The distinctive Polaroid look—caused by uneven color saturation, underdevelopment or overdevelopment, or just daily atmospheric effects on the developing photograph—is emphatically analog. In an age of high resolution, portable printers, and camera phones, the Polaroid’s appeal to some has something to do with ideas of nostalgia and authenticity. Convergence has transformed who uses these media and for what purposes, but it hasn’t eliminated these media.

References

Anderson, Monica & Jiang, JingJing. “Teens, social media & technology 2018.” Pew Research Center for Internet and Technology. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

Carr, Nicholas The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (New York: Norton, 2010).

Hogan, Marc. “This Is Not a Mixtape,” Pitchfork, February 22, 2010, http://pitchfork.com/features/articles/7764-this-is-not-a-mixtape/2/.

Jenkins, Henry. “Convergence? I Diverge,” Technology Review, June 2001, 93.

Johnson, Steven Everything Bad Is Good for You (Riverhead, NY: Riverhead Books, 2005).

Lewin, Tamar “If Your Kids Are Awake, They’re Probably Online,” New York Times, January 20, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/education/20wired.html.

Livingstone, Gretchen. “Americans 60 and older and spending more time in front of their screens than a decade ago.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/18/americans-60-and-older-are-spending-more-time-in-front-of-their-screens-than-a-decade-ago/

New York Times, editorial, “The Half-Life of Phones,” New York Times, June 18, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/20/opinion/20sun4.html1.

White, Livingston A. “Reconsidering Cultural Imperialism Theory,” TBS Journal 6 (2001), http://www.tbsjournal.com/Archives/Spring01/white.html.

Convergence is a feature of recent media environments where texts cross multiple media platforms and audiences travel between them with ease or when technologies take on multiple functions as when cellphones are used not just to talk and text but to listen to music, watch videos and play games.

The media context, usually digital and online but not essentially, where one-to-one, one-to-many and many-to-many forms of discourse prevail. Newspapers, radio and TV are regarded as examples of old media.

The way in which media audiences and users ae able to annotate, use, comment on, remix, and influence culture.

The idea that a dominant culture might result in changes to another culture’s social institutions and values. This might occur by pressure from the dominant culture, attraction by the culture being changed, or even by force or bribes. Cultural imperialism is often seen as a key part in the process of globalization.

The organization of activities on a global scale is called globalization. It involves interdependence and often these activities are in real time.

The degree of one’s attention is absorbed by and focused on a media text.