Introduction

Gabbie Mangaser

For first through fourth-generation students of Filipino descent in American universities, the distance between themselves and their heritage seems far away, from a time of family history long ago, from unspoken immigration stories, or from being thousands of miles away from theirs or their family’s homeland. While museums and archives may have some remnants of Philippine and Filipino history, the catalog can depict objects and photos as static, rendering their origin cultures and portraits of people as relics of the past.

Winter Quarter 2024 marked the first iteration of Knowledge Kapamilya, a space for Filipino/a/x American students at the University of Washington to engage with the Philippine Collections at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. The Philippine Collections consist of over 4,200 cultural belongings and archival materials, whose provenance includes donors that were military officers, academic or teaching personnel, colonial administrators, tourists, and Peace Corps volunteers. The regions of Luzon and Mindanao are well-represented, with much less from the Visayas, or simply labeled generally from the Philippines and Philippine Islands. Visitors and community members touring the main storage spaces will immediately observe the numerous weapons–swords, daggers, bows and arrows, and spears–alongside textiles, carvings, headwear, model houses and watercraft, and the like. Many will also laugh and recognize household items, wondering how they “end up in a museum,” and possibly feel an inkling to donate their own belongings.

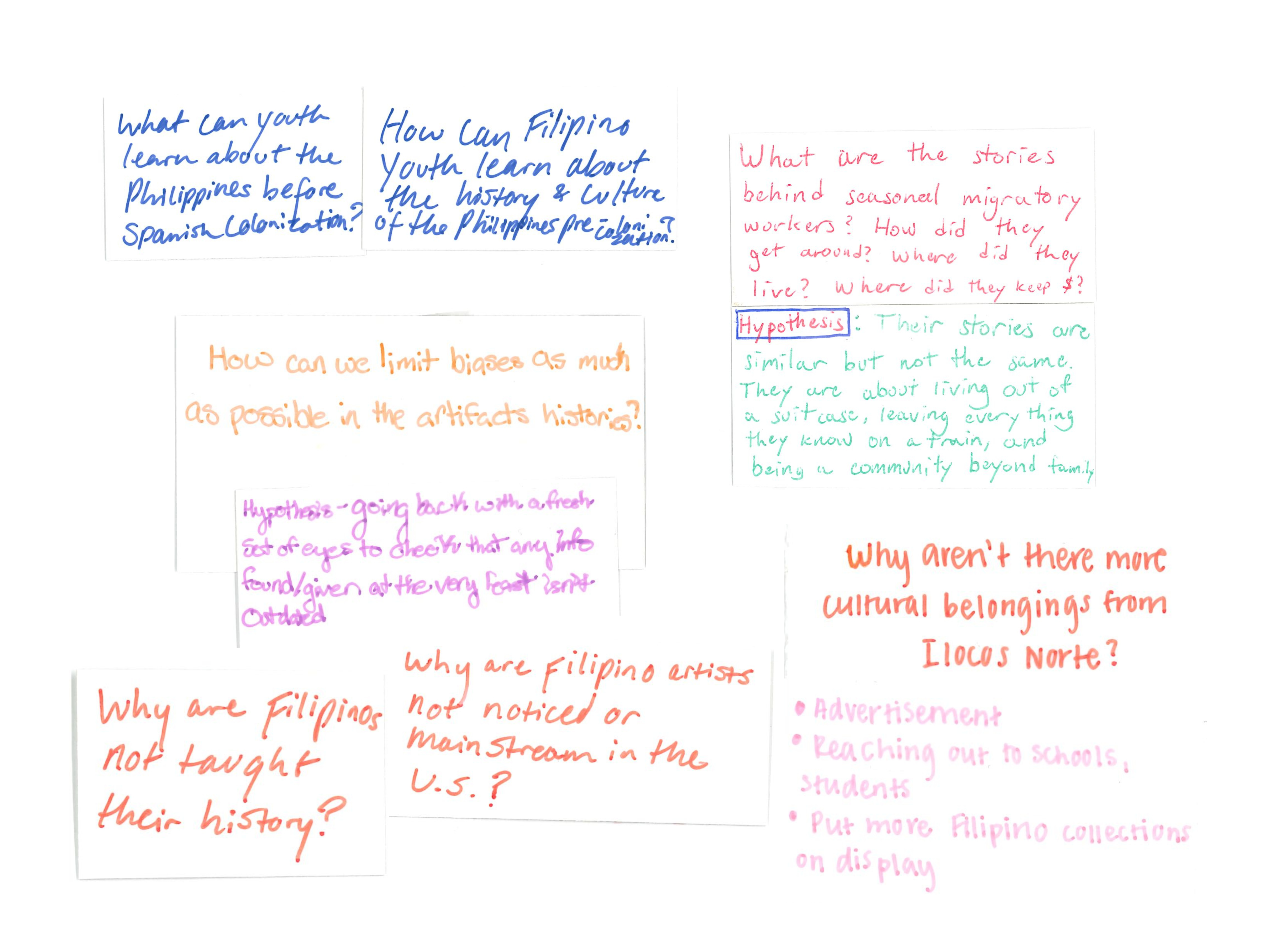

For Filipino American students, cultural belongings can be catalysts for heritage learning. The 2024 cohort of Kapamilya thought intentionally about how Philippine objects end up in the museum: who were the donors? Why were they there? How did they view Indigenous Philippine peoples, or Filipino nationals? Can we rely on the information that collectors give us about belongings? Why is it labeled this way, and why isn’t the culture of origin more specific? Why would the museum accept this? What is the use of this object? How is it significant? What is the use of the object now that it’s in the museum? How should we label objects then?

Beginning with these questions, students began to look beyond the catalog card (an activity affectionately called “Look with your eyes, not with your mouth”) and connect the provenance of an object to what they know about Philippine and Filipino American history, and with their families’ stories of migration and immigration to the states. For example, materials from the Philippine American War, such as a revolutionary flag from the Battle of Santa Cruz in 1899 bring a new element in learning about US imperialism in the Philippines. With pieces ranging from the war to world’s fairs and towards the mid-20th century, students were able to describe tools in which the US colonized the Philippines which were minute details upon examining donor information and object provenance. Kapamilya also identified bias within the catalog cards, noticing that “the record” can often be one-sided, written with information attributed to a donor who does not belong to the origin community and whose perspective can be shaped by Western hegemonic ideals.

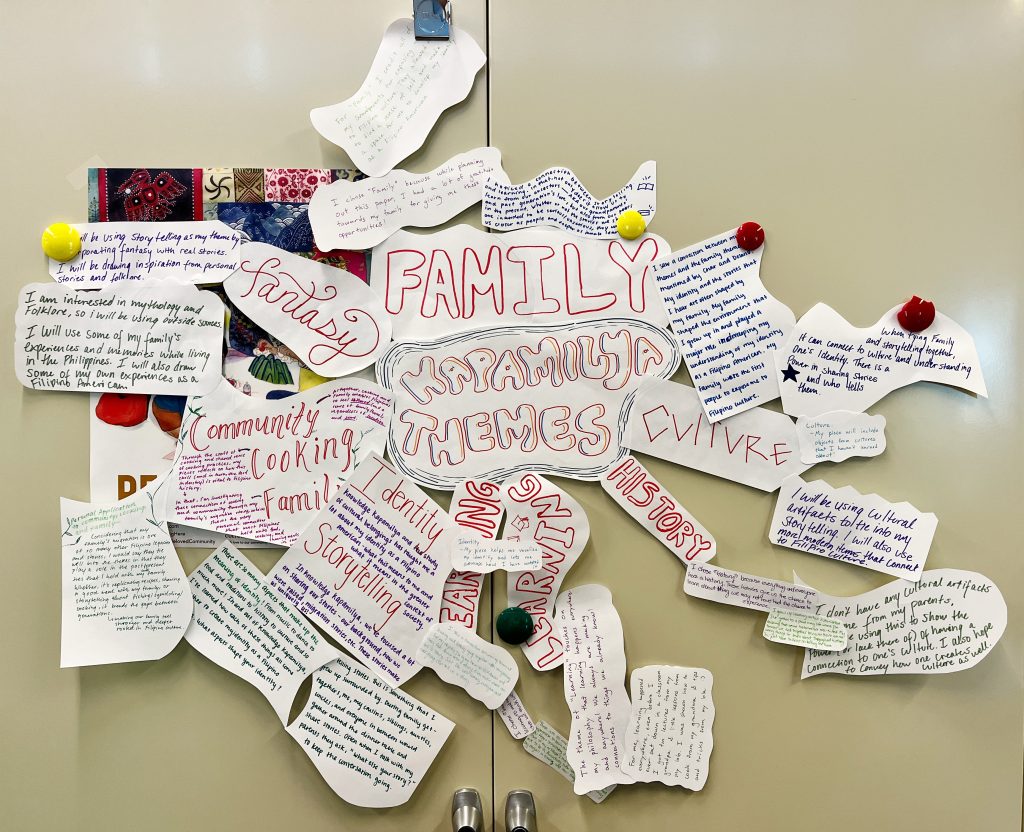

More importantly, kapamilya employed kwentuhan[1][2] alongside their questioning of the museum, ethics of collecting, and provenance. Kwentuhan, or Filipino talk-story, gave students the ability to think critically about certain themes in Filipino American history based on theirs and their peers’ family stories and experiences. For example, particularly through immigration experiences and histories from first through fourth generation students, emerged a range of stories that depict the multiple Filipino waves of migration.

The following chapters elucidate several questions that students referred to throughout the year:

- How do you connect with your family, and what is learned (or not learned) from them?

- How do you see yourself, and how does it change over time?

Between asking questions through the collections and answering them with what they could observe within the catalog card and Filipino American history through their families’ stories, students reflected on their own relationships between themselves, their peers, and their relatives. In summary, they identified the many opportunities to connect with their kapamilyas–whether born into or chosen–through storytelling, through artifacts, through music and dance, or through cooking. They reflected upon their own intrapersonal relationships: how they see themselves versus how they view the world, their environment, and the people around them is ever-changing and fluid. Finally, through story-telling, students’ friends and peers can also bring out intrinsic knowledge from experience; knowledge that comes out through conversation and cultivating shared space.

In essence, kapamilya embodied how museum collections have the ability to bring out stories and understanding when their respective communities have access to them.

- Jocson, Korina M. 2008. “Kuwento as Multicultural Pedagogy in High School Ethnic Studies.” Pedagogies: An International Journal 3: 241-253. ↵

- Gutierrez, Rose Ann E., Hazel Piñon, Marie Trisha Valmocena. 2023. “Co-creating knowledge with undocumented Filipino students: Kuwentuhan as a research method.” New Directions For Higher Education, no. 203 (September): 77-92. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20478 ↵