Grandpa Joe’s Story

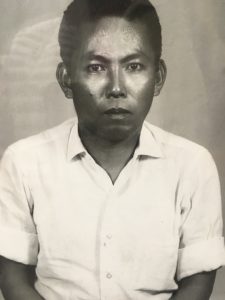

A photographer to some, a fellow fisherfolk to many, my granduncle Jose, more commonly, grandpa Joe, was a man of many trades- and in turn, mysteries. As my dad excitedly rustles in his chair at the topic of my grandpa Joe, I knew I was in for a treat when garnering research for the project I had at the Wing Luke Museum. With seemingly little information online at that time, I sought out my dad’s account of him and the memories they shared in piecing together his life especially being the first person in my family to have left the Philippines having worked in Alaska apart of many fisherfolk that have made a large impact in Filipino American history. However, now being able to reflect on that project as a freshman in university, I thought of revisiting this story through Knowledge Kapamilya and drawing on the overarching impact the fishing industry and culture around food and cooking has had on Filipinos throughout different generations: In particular, from my grandpa Joe and to me today.

For context, my grandpa Joe left Pangasinan in the early 1950’s to work for the P.E. Harris Cannery in King Cove, Alaska. My dad recounted his departure as an outlet for him and his younger brother, my grandpa Buddy, to have financial security beyond tilling rice plantations back in the Philippines. With dire conditions of inequitable access to higher education and stable housing, it was evident to them that they needed new jobs to meet their necessities and set better foundations for their future. Being the older brother, grandpa Joe took the opportunity abroad to seek employment, which led him into the fishing work in Alaska. In that, he was able to send remittances and American goods back home in support of grandpa Buddy, my dad, and the whole family. Quite the character, my dad remembers being sent marshmallows regularly, assuming it was a key aspect in the American diet. But in turn, he found that grandpa Joe himself just really enjoyed them. As a whole, these remittances and personal photographs from his film camera were all that my dad and his siblings could grasp as to who my grandpa Joe was.

With just knowing these little quirks of my grandpa Joe, it remains a mystery whether he ever had a family of his own while in the US, or what his true aspirations could’ve been if not systemically forced into fishing work. But, it was clear that his financial support back home was a sacrificial form of expressing the love he had for the family of his time and those coming after him.

In honor of his story, I have come to learn that his experiences are shared among many other Filipinos who’ve invested their lives in the fishing industry throughout the West Coast. Especially, in considering the sacrificial type of love that comes at setting aside their aspirations, ideas of “home”, and accessibility to communicate – all for the very people they want to nurture. But, why is that? Why did it have to entail sacrifice?

It’s important to note the US possession of the Philippines in late 1800’s and coming 20th century had heavily impacted the migration waves of Filipinos coming into the US. In paving the ways the education system was settled from the cities to rural parts of the Philippines, there were plenty of positive connotations around working in the US, which motivated a lot of Filipino men to work in farms and fishing canneries throughout the West Coast. In parallel to many of the financial struggles Filipinos were facing in the homeland, the opportunity to leave felt like a step into seeking better education, financial means, and as a whole, just better lives. However, in that, it was discovered that a lot of work within these farms and canneries had struggled to keep protections on their workers both in and out of the workplace.

With living in run-down shacks on-season to vacant hotel spots off-season, being selected for the “…least desirable jobs”[2], and little physical protections for the equipment in the workplace, it was clear to many of the Filipino workers that this cyclical form of discrimination and mistreatment should not be deemed tolerable, especially in the demands and aspirations they had when coming abroad.

In taking up means of grassroots organizing, many Filipino fisherfolk, taking the titles of “Alaskeros”, unionized to build support and empowerment among the large number of Filipinos in the industry, all sprawled throughout the region. Leading in 1933, the Cannery Workers’ and Farm Labor’s Union Local 18257 was formed primarily by Alaskeros working together and deliberating on their values given their shared sacrifices as Filipino migrants. By amplifying their voices in this matter, they tackled to address systemic issues both in and out for workplace, for the betterment of workers’ lives and the capacity for them survive and keep their families in the Philippines sustained. In this, it took means of labor strikes to community gatherings for their efforts to contribute into the social fabric of Filipino community and identity in Seattle, and generally, the US.

Considering my grandpa Joe’s departure was after the settlement of the Cannery Workers’ and Farm Labor’s Union Local 18257 in 1933, I found that the life and work of my grandpa Joe were heavily shaped by the work of many Filipino labor organizers and older Alaskeros who fought for adequate wages and better living conditions. Even living at the NP Hotel, a vacant hotel spot in the 1950’s and 1960’s, it’s clear that the work of labor union were definite conversations my grandpa had and it was integral to his identity being a Filipino fisherman. My grandpa Joe’s story taught me that food can be seen as integral to Filipino identity in that its industries, from the farms to the canneries, were strengthened by Filipino communities in the diaspora given the struggles in its earlier waves of migration and it can provide a historical context of Filipino labor power and cases of sustaining Filipino virtue.

- A.E Lopez, Butchering the salmon, 1930s, Photograph, National Pinoy Arcives, FANHS Collection, Alaska. ↵

- Crystal Fresco, "Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers Union 1933-39," The Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 1999, https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/cwflu.htm. (accessed June 4, 2024). ↵