Phase II — A Place for Some of Our Best Students

Our Japanese students deserve friendliness at this difficult time. There is little doubt but that they will all be taken away shortly. Even though they may be permitted to stay until the end of the quarter, many of them have the serious problem of getting their houses in order, and so will be inclined to drop out of school before the end of the quarter.

UW President Lee Paul Sieg[1]

President Sieg wrote these words to UW deans just days after the entire West Coast (all of California and the western halves of Oregon and Washington) was designated a restricted military area under General John L. DeWitt’s Public Proclamation No. 1.[2] The proclamation made forced evacuation of the Japanese Americans inevitable. With that inevitability the University of Washington shifted gears, from boosting morale by helping Nikkei students cope with restrictions to adopting a leadership role in transferring students to university and colleges outside the West Coast.

On the same day that President Sieg sent his letter off to deans on campus, he also began soliciting help from presidents of colleges and universities across the country. According to Robert O’Brien, assistant to the Dean of Arts and Sciences and faculty advisor to the Japanese Students Club, Sieg “opposed the evacuation, but when it happened he felt that the University of Washington was under obligation to protect their students, and he wrote letters to college presidents all over the United States indicating his faith in the American qualities of Japanese Americans, and urging these people to take our former students who were to go to the relocation assembly centers.”[3] Tom Bodine of the American Friends Service Committee remembers that “the staff at the University of Washington, from the president down, worked hard at this project of helping Japanese American students on campus get into colleges in the east. It wasn’t easy because colleges in the east were prejudiced against them as everybody was. Fearful that they were going to be traitors or something.” [4] A letter to Barrison C. Dale, president of the University of Idaho was posted on March 6, 1942; an identical letter was mailed to President Ernest H. Wilkens of Oberlin College on March 10, 1942:[5]

Because of the exigencies of war, the Army has given advance notice of the evacuation from this area of both native and American born Japanese. Between three and four hundred members of the latter group are students who have been enrolled in the University of Washington this year.

We have known these students as excellent scholars and young people who have contributed their leadership to our classroom work and constructive campus activities. As a group, their scholarship is well above the University average. As citizens of the University community, they have been loyal supporters of academic and defense activities.

Some of these students will wish to continue their education in institutions away from the Pacific Coast area. We are interested in seeing, in so far as it is possible, that the students of this group be given every opportunity to do so.

This letter is in the nature of an exploratory note to inquire whether your institution would be in a position to open its doors to a few well-qualified American students of Japanese ancestry.

Responses to Sieg’s letter varied. According to a Japanese Evacuation Report written by Tom Bodine of the American Friends Service Committee (this Quaker group was also working to relocate students), by March 26 Sieg had received twelve replies (out of approximately thirty letters sent) with ten universities agreeing to take some students.[6] A memo from the office of Student Affairs published a list of those universities and colleges willing to take Nikkei students, along with those who could not “accept students at this time.”[7]

The University of Wisconsin was one institution declining to take Nikkei transfer students. Sieg responded to Wisconsin’s President Dykstra, noting that many of the institutions were “a little hesitant about receiving these students of the Japanese race.” He went on to warn:[8]

A few minutes thought on the part of many of us will make us understand that an effort to help these capable students is more than merely a sentimental gesture of good-will. It is certainly that, because unless we take away the citizenship of these individuals, we shall run the risk of having a large group of American citizens who can’t have too much enthusiasm and loyalty for their country after this war is over. But the practical side is that there is need of training these individuals for service with their own people, many of whom will find themselves in closed communities in the interior of the country. These communities will need the services of doctors, lawyers, nurses, teachers, and others. Why shouldn’t they be served by persons of their own race, thus relieving the members of the Caucasian race for war service elsewhere.

One university, Montana State, was forced to delay acceptance of students due to public and political pressure. Ernest O. Melby, President of Montana State University, explained to Sieg “that a considerable number of people called Governor Ford and insisted on Board action concerning the matter,” he went on to clarify his personal views:[9]

I am, of course, personally very anxious that we exhibit the spirit of our democracy in the solution of our domestic problems this way. For this reason I have expressed my personal opinion on a number of occasions to the effect that the Japanese should not be excluded from our educational institutions. It may be, however, that public sentiment on the problem will become so strong that a mere president’s attitude will be of no consequence.

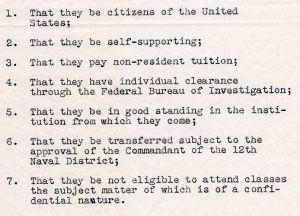

Other universities were willing to accept students but with restrictions. The University of Colorado sent this list of requirements:[10]

This personal appeal from Sieg to other university presidents was essential in the early move to relocate students prior to the establishment of any official process and organization. At this point, during the spring of 1942, the relocation of Japanese American students depended entirely on the initiative and good will of college administrators. The case of Oberlin College provides a good illustratration.

Oberlin President Ernest H. Wilkens responded to Sieg’s letter with an invitation to four UW students (Kenji Okuda, Norio Higano, Richard Imai, and Koichi Hayashi) recommended by Harry Yamaguchi, a sophmore at Oberlin. Robert O’Brien quickly responded on Sieg’s behalf, thanking Wilkens for his “generosity and cooperation in helping us find a place for some of our best students.” Other letters followed concerning possible substitutions for the students and the issue of community acceptance. By the fall of 1942, another UW student, Bill Makino, entered Oberlin; Kenji Okuda joined him that winter.[11] One student wrote O’Brien during the summer of 1942:[12]

There are no exceptions or restrictions. The war hasn’t affected their policy a bit. . . . [T]here are eleven of us Nisei students at Oberlin, and my only regret is that some more of the Nisei students are not here to benefit by Oberlin democracy. It is indeed a pleasure and an inspiration to attend such a school where you are treated on an equal basis with everyone else.

The support of the Nikkei students extended beyond the college campus to the community at large. An editorial in the Oberlin News-Tribune praised the students as “fellow Oberlinites” who though of Japanese ancestry “have in every way behaved according to the best traditions of the land of their birth and rearing and citizenship.”[13] Oberlin’s enrollment of Japanese American students quickly jumped from two in 1941 to twenty in 1943.[14]

The University worked with the University of California, Berkeley and other west coast institutions to coordinate efforts to help Nikkei students. A conference, hosted by the Pacific coast YWCA-YMCA, on Japanese American Students and Faculty Members, was held at Berkeley in March 1942 and recommended that an umbrella Student Relocation Committee be set-up to “facilitate the evacuation of the Nisei and alien students.” Robert O’Brien was offered the position to head this effort but turned it down and instead Joseph Conard was hired. Regional committees in Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles were also created.[15]

The University of Washington established the Seattle-based Student Relocation Committee chaired by Robert O’Brien. The committee’s mandate was: “1) to gather data on the Nisei in the Pacific Northwest; (2) to collect character references for the students; (3) to help relocate Nisei in other colleges after their evacuation.”[16] The Student Relocation Committee later merged with other organizations to form the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) in May of 1942, which operated with the blessing of the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Robert O’Brien later took an official war leave from the University of Washington to become the director of the NJASRC.[17]

Other faculty members joined in the effort to support Nikkei students. A letter soliciting scholarship funds made the faculty rounds in early April of 1942. The letter began with George Yamaguchi’s somber note, seen tacked on a study room door: “Working on the final term paper of my career. Please do not disturb. Let’s make it a masterpiece.” Faculty were urged to donate funds so that George and other students could continue their education elsewhere. Continuation of their education and training would “enable them to aid the war effort of the United States” and make “it possible for them to serve our country to the maximum of their ability.”[18] George Yamaguchi would later be incarcerated first in Tule Lake and then Mindoka, enlist in the Army in 1944, and die in Okinawa in 1945. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. [19]

The process for transferring a student was rigorous. By July of 1942, the Department of War and War Relocation Authority (WRA) required dossiers for each student (containing references and transcripts) and mandated eight additional steps, including security clearances from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Office of Naval Intelligence, Army intelligence and the War Department.[20] In addition, colleges and universities needed to be cleared by the Army and Navy before Japanese American students could enroll. During the first part of the war, smaller colleges were more likely to receive clearance rather than the larger state universities, which were more heavily involved in wartime research or military training activities. As of September of 1942, 111 of the 156 colleges that had accepted Japanese American students received clearance from both branches of the military.[21]

Even after a student had been accepted to a college, obstacles remained. In April of 1942, Kenzo Kuroda, a UW student on his way to the University of Minnesota was detained in Nampa, Idaho. He sent an urgent telegraph to the UW’s Dean of Men. Dean Newhouse in turn asked Pastor Leroy Walker, of the First Methodist Church in Nampa, to intervene on Kuroda’s behalf. Newhouse ended his message: “Thank you for a big favor to a deserving American citizen.” Kuroda was released and allowed to continue his train journey to St. Paul. Walker congratulated Newhouse on his tenacity: “We wish to commend your spirit and your faithfulness in following up your students and in trying to see that they get a ‘square deal.'”[22]

Idaho became the center of another controversy regarding relocated Japanese American students from the University of Washington. Six Japanese American students were accepted to the University of Idaho in Moscow in the spring of 1942. They arrived to face vigilantes demanding their expulsion from the town and the university. Two female students were placed in protective custody in the town jail. One student’s letter describing the incident was later published in the Pacific Citizen, the newspaper of the Japanese American Citizens League.[23]

We had our lunch in the face of the deputy sheriff who is called the Bull Moose. He sure hates us. The jailer was talking to someone over the telephone, and said that he is afraid that a mob will come to lynch us tonight.

They don’t have curfew here, but I’m not free in jail, that’s sure, and I’m getting a terrific cold since the place is freezing. Let’s hope Mr. D–– gets his brother in Chicago to take me. Mrs. B–– will mail this letter.

I’ll write you another letter as to how it will turn out, and in case you don’t hear from me, you’ll know what has happened.

Please write. I’m scared.

The governor of Idaho, Chase A. Clark, further aggravated the situation by stating that, “no out-of-state Nisei would be allowed to enroll in any of the state’s institutions of high learning.” The students later enrolled at Washington State College in Pullman, directly across the border from Idaho.[24]

As the May 1 deadline for the removal of all Japanese from the Seattle area loomed, the university produced a number of memos outlining withdrawal and transfer procedures.[25] By the middle of May, O’Brien reported in the Daily that “fifty-eight Nisei students were placed in 15 different colleges in 12 states.”[26] The university, at President Sieg’s insistence, also eased graduation requirements for seniors faced with relocation. Years later, O’Brien recollected:

Many Nisei were about to graduate but they were in the last quarter, not allowed to attend the University because they were sent to Puyallup and other relocation centers. President Sieg felt that the better service would be done if they were given degrees. Some of these deans — I try not to remember who they are — felt that this was outrageous, that the degree could not be given to a person who had had eleven twelfths of their education. But President Sieg knew what he thought was right, and the University awarded students who came within – completed 11 quarters, and one of the most encouraging things for those behind barbed wire was when President Sieg and some of his deans went to the relocation centers and gave these young people their degrees. I may be prejudiced for the University of Washington because it’s my alma mater but I don’t think there was anything like this going on other places. We also carried our extension courses to some of the relocation centers as a service to people whose parents were still taxpayers even though they weren’t living with us.[27]

O’Brien continued his work with the Student Relocation committee (later to become the Pacific Northwest Student Relocation Council) throughout the summer by providing updates to UW students at Camp Harmony, the Puyallup assembly center where most of Seattle’s Japanese were detained, and Minidoka, the “permanent” concentration camp in Idaho.[28] Student questionnaires were distributed to elicit information from students wishing to relocate. Students were asked about citizenship status, religious preferences and life goals.[29]

By the end of the war more than 3,000 Japanese American students had been placed in more than 500 colleges and universities in forty-six states.[30] Both the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council and the War Relocation Authority would laud the student relocation effort as contributing to increasing opportunities for Japanese Americans across the country.

The story of student relocation is a story of pioneering and of rebuilt faith. Most of the 3000 students who have gone from camp to college have gone to areas of the country where people of Japanese ancestry were almost unknown. As ambassadors for the entire Japanese American group, they have paved the way for others to follow. They have stimulated and encouraged their families to come and join them. Most important, perhaps, their pioneering has helped large sections of our population to acquire a new understanding of American principles and fair play. And in the process their faith in themselves and in their whole future in this country.[31]

And John H. Provinse, Chief of the Community Management Division of the War Relocation Authority, touted the program in his article, “Relocation of Japanese-American College Students: Acceptance of a Challenge”: [32]

From the point of view of the students, this adjustment program has enabled a number of the most able and ambitious young people to break away from the isolation of the relocation centers and to prepare themselves for making contributions to the life of the country of their birth and loyalty. To many of them, embittered by the apparent disregard of their citizenship, it was a welcome gesture of friendship and recognition of their identity with other young Americans. To many of them also, it will bring an opportunity for a career in work that was closed to them in their former homes. To some of them, it will mean establishing a home for themselves and their families in a portion of the country where lack of concentration removes them from the category of a “minority problem,” and where they are accepted more generally on individual merit. This acceptance is one of the goals of the WRA program.

- Lee Paul Sieg to Dean Faulknor, 6 March 1942, UW School of Law, Acc. 84-008, UW Libraries Special Collections. Photograph of Lee Paul Sieg taken from the 1941 Tyee. ↵

- An interesting aside: Robert O'Brien credits UW professor Calvin Schmid with ensuring that eastern Washington and Oregon remain out of the restricted area.

One of the things that probably doesn't get recorded is that sometimes people who work in quiet ways can be very effective in making democracy function, and one of these was Calvin Schmid who was asked by the military to draw the maps and the plans for the evacuation of Japanese and Japanese Americans. Calvin was looking at a map of California, and he drew the line straight north so that the eastern parts of Oregon and Washington would be still available for Japanese and Japanese Americans, and these people did not have to be evacuated. I doubt if many people know this about Professor Schmid because he's a quiet person about this sort of commitment, but he had this commitment. The result was, of course, that we could relocate students in Pullman and Whitman College and others in the eastern part of the state.

Robert O'Brien, interview by Howard Droker, April 24, 1975, Robert W. O'Brien, Acc. 2420-003, UW Libraries Special Collections. See further excerpts from the interview. Apparently eastern Oregon and Washington were excluded because "the natural forests and mountain barriers" divided the states while in California these natural barriers were located in the eastern half of the state so the entire state was designated a restricted military area. J.L. DeWitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1943), 15. ↵ - Robert O'Brien, interview by Howard Droker, April 24, 1975. See further excerpts from the interview. The list of proposed list recipients for this letter included major public universities such as the University of Michigan and Ohio State and smaller institutions such as Ohio Wesleyan and Wooster. See Proposed list of college presidents to whom the form letter would be sent, UW President, Acc. 71-34 Box 129, UW Libraries Special Collections. SCAN PDF ↵

- Thomas Bodine, interview by Antonio Leal, August 17, 1991, American Friends Service Committee Oral History Interviews Series #400, p. 87. ↵

- UW President L.P. Sieg to Oberlin College President Ernest H. Wilkins, 10 March 1942, Correspondence Series, Ernest H. Wilkins Collection, Nisei folder, Oberlin College Archives. See Correspondence between Oberlin College and the UW. The letter from Sieg to Dale can be found in Vice President for Student Affairs, Acc. 71-38, UW Libraries Special Collections while a letter from Sieg to University of Colorado President Robert L. Stearns dated 9 March 1942 is in the UW Office of the President records, 1854-2015, Acc. 71-34 Box 129, UW Libraries Special Collections. The letter was drafted by Robert O'Brien at the request of President Sieg. See memo from O'Brien to Sieg, 6 March 1942 in UW Office of the President records, 1854-2015, Acc. 71-34 Box 129, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- Japanese Evacuation Report #7. Joseph Conard, Collector, Hoover Institution Library and Archives, Stanford. ↵

- Information and suggestions for evacuees, Vice-President for Student Affairs, Acc. 71-38, UW Libraries Special Collections. SCAN PDF Those listed as willing to accept transfers were University of Idaho, University of Colorado, University of South Dakota, University of Nebraska, University of Kansas, Kansas State College, Iowa State College, University of Montana, Montana State College, University of Minnesota, Oberlin College, University of Chicago, Northwestern University, University of Utah, University of Denver, State College of Washington, and Gonzaga University. Those unwilling were Iowa State University, University of Wisconsin and the University of Illinois. The twenty-five Japanese American students accepted at Earlham College between 1942 and 1945 are listed in the description of the Uyesugi Japanese American Collection, Earlham College Libraries, Richmond, Indiana. For an interesting discussion of this situation at the University of Pennsylvania, which denied admission to all Japanese Americans between Pearl Harbor and 1944, see Greg Robinson, "Admission Denied," Pennsylvania Gazette, Jan./Feb. 2000. ↵

- UW President L.P. Sieg to C.A. Dykstra, 6 April 1942. UW Office of the President records, 1854-2015, Acc. 71-34 Box 129, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- Ernest O. Melby to L.P. Sieg, 4/20/1942. UW Office of the President records, 1854-2015, Acc. 71-34 Box 129, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- Letter from the University of Colorado outlining student requirements for transfer, 23 March 1942, Vice-President for Student Affairs, Acc. 71-38, UW Libraries Special Collections. See also the further interpretations and letter of April 17, 1942. SCAN PDFS ↵

- See Correspondence between Oberlin College and the UW: Sieg to Wilkins, 10 March 1942, Wilkins to Sieg, 19 March 1942, O'Brien to Wilkins, 26 March 1942, O'Brien to Wilkins, 11 April 1942, O'Brien to Wilkins, 29 June 1942, O'Brien to Ruth Forsythe, 22 August 1942, Forsythe to O'Brien, 27 August 1942. All letters courtesy of the Ernest H. Wilkins Collection, Oberlin College Archives. Makino's and Okuda's entry into Oberlin was announced in the Pacific Cable on September 9, 1942 and January 18, 1943. ↵

- Student letter quoted in Robert O'Brien to Ernest H. Wilkins, 29 June 1942. See Correspondence between Oberlin College and the UW for transcript. ↵

- Editorial quoted in "Oberlin Finds No Cause to Regret Admitting Nisei," Minidoka Irrigator, June 26, 1943, p. 3. ↵

- Figures from Robert W. O'Brien, The College Nisei (Palo Alto: Pacific Books, 1949), 141. ↵

- See announcement of the meeting in "'Y' Conference to Consider Aid for Student Evacuaees," Daily Californian, 20 March 1942. A memo of the meeting summarizes the conference discussion and recommendations: Memo to President Sieg re: Conference on Japanese American Students and Faculty Members, 25 March. 1942. UW Office of the President records, 1854-2015, Acc. 71-34 Box 129, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- "Committee Formed to Assist Nisei," University of Washington Daily, April 22, 1942. ↵

- For more information on the creation of the NJASRC see Austin, Allan W. From Concentration Camp to Campus : Japanese American Students and World War II. University of Illinois Press, 2004. For documents relating to the establishment of the NJASRC see M.S. Eisenhower to C.E. Pickett, 5 May 1942 and John J. McCloy to C.E. Pickett, 21 May 1942. (Letter also reproduced in the American Friends Service Committee publication, "Japanese Student Relocation: An American Challenge.") Records of the American Friends Service Committee, Midwest Branch, Advisory Committee for Evacuees, 1942-1963, ACC. 4791-001, Box 25, UW Libraries Special Collections. About O'Brien's appointment as director see Robert O'Brien, interview by Howard Droker, April 24, 1975. ↵

- Form letter to faculty, 10 April 1942, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, BANC MSS 67/14 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. The letter was signed by five faculty members: E.R. Wilcox of Engineering, Howard Nostrand of Romance Languages, Robert O'Brien of Sociology, Dean Newhouse, the Dean of Men, and Linden Mander of Political Science. ↵

- According to the Jerome County listing in the World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing Army and Army Air Forces Personnel from Idaho, he died during the war of non-battle causes. Jerome County is the location of the Minidoka Relocation Center. Seventeen other Nikkei are listed as casualities from the county. Another source, NCOs the Military Tradition, a publication of the U.S. Army Intelligence Center, states that Yamaguchi, a member of the Counter Intelligence Corps, was killed in a plane crash on August 13, 1945 in Okinawa. ↵

- Evalene Hall Jenness provides a more detailed description of the process. "This plan was drastically altered in July 1942 when the Department of War and the WRA signed a memorandum of agreement pertaining to the student relocation program. The agreement listed an eight-step process to facilitate the transfer of Japanese American students. The procedure now included a dossier on each student that went to the project director of the assembly or relocation center that included many documents such as the student's questionnaire form, high school and college transcripts and letters of references. The project director sent the completed application to a WRA regional director with the project director's student recommendation, the rest of the dossier as well as a copy of the applicant's fingerprints. The regional director then forwarded 'the essential data to the appropriate FBI, ONI [Office of Naval Intelligence], and G-2 [Army intelligence] offices for a record check' of each student. Once the record check was completed, the student's dossier was sent to the WRA office in Washington which passed it on to the Division of Military Intelligence (DMI) at the War Department for a clearance check. The DMI granted or denied clearance, notified the WRA, then the WRA sent word to the NJASRC in Philadelphia. The Council notified the school as well as the student of approval. The WRA then issued a pass to the student so he or she could travel. Lastly, the DMI, 'inform[ed] the Commanding General of the Military or Corps Area of the presence in his area of such relocated student.'" Jenness, Evaline Hall, "Japanese American College Students during the Second World War: The Politics of Relocation," (PhD diss., Indiana University, 1993), p.174-175. ↵

-

"Facts about Student Relocation," Pacific Cable, 23 September 1943, p. 1.

John H. Provinse, Chief of the Community Management Division of the War Relocation Authority, further explained why certain schools received clearance:

Despite a sifting process designed to eliminate the possibility of releasing any student of doubtful loyalty, the first lists of cleared educational institutions were limited to rather small schools in locations removed from defense centers or other installations of military importance. In addition to these restrictions, there were a certain number of schools in the cleared category which were unwilling to accept Japanese-American students because of misunderstandings as to the status of the students or the nature of the program or unfavorable sentiment in the community. At the same time, a number of the larger institutions were eager to extend a welcome to this dislocated group, but the presence of training or research programs being carried on for the Armed Services precluded their admission.

Provinse also noted in a later article, "Relocation of Japanese-American College Students: Acceptance of a Challenge," Higher Education 1, no. 8 (1945), that until January of 1944 there were a number schools prohibited to Japanese Americans:At that time the Office of the Provost Marshal General assumed responsibility for security measures for all branches of the Armed Forces; and the regulations were relaxed to provide that if a student of Japanese ancestry would submit a Personal Security Questionnaire and obtain the approval of that Office, he might attend any school in the United States outside the military areas of the West Coast. For the first time it was possible for the Nisei to attend such schools as the University of Chicago, Yale, Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, and some of the large State Universities in the Middle West. After a trial period during which the number of denials was negligible, the last restrictions were removed on August 31, 1944, and Japanese-American students may now be accepted at any educational institution on the same basis as other schools. ↵

- See: Telegraph from Kuroda to Newhouse, 7 April 1942, Telegraph from Newhouse to Walker, 7 April 1942, Walker to Newhouse, 4 April 1942 and Newhouse to Walker, 13 April 1942. All in: Vice-President for Student Affairs, Acc. 71-38, UW Libraries Special Collections. SCAN PDF ↵

- See "Nisei Girl Writes from Idaho Jail," Pacific Citizen, June 11, 1942, p. 5. See Pacific Citizen collection, Densho Digital Repository. The UW attempted to get new accommodations for the students, see Joseph W. Conard to Robert O'Brien, 20 April 1942, Vice President of Student Affairs, Acc. 71-38, UW Libraries Special Collections. SCAN PDF ↵

- Carl Ronning, a student at Washington State College, published an open letter to the Governor of Idaho in the Idaho Argonaut college newspaper on May 3, 1942. This article was later reprinted in the Daily and in the Washington State College paper, The Evergreen on May 6, 1942. In contrast to the University of Idaho, the College of Idaho accepted twenty-one Nikkei students, approximately 10 percent of the student body. William W. Hall Jr., The Small College Talks Back: An Intimate Appraisal (New York: RR Smith, 1951), 67. ↵

- See: Information and suggestions for evacuees, Procedure for students wishing travel permits to attend other colleges, Procedure for withdrawal for evacuating Japanese students, and Evacuation of Japanese Students, Vice-President for Student Affairs, Acc. 71-38, UW Libraries Special Collections. ↵

- "University Places 58 Nisei in Other Schools," University of Washington Daily, May 20, 1942. The local Student Relocation committee chaired by O'Brien, had secured admissions in Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Massachusetts, Missouri, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, Utah and Washington. ↵

- Robert O'Brien, interview by Howard Droker, April 24, 1975. See further excerpts from the interview. There seems to be some confusion about holding a graduation ceremony at the Puyallup Assembly Center. J.J. McGovern, the Puyallup Assembly Center Manager, wrote Sieg asking if a UW representative could come to the center. See J.J. McGovern to L.P. Sieg, 22 June 1942. Sieg responded back that the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Edward H. Lauer, had offered earlier to come to the center and that McGovern should contact Dean Lauer to make arrangements. L.P. Sieg to J.J. McGovern, 24 June 1942. There is no mention in the Camp Harmony News-Letter or in the Minidoka Irrigator of a UW graduation ceremony. There is a brief mention of students receiving their diplomas by mail in a local newspaper, see "Japanese to Get Diplomas by Mail,"Seattle Times, 2 June 1942. ↵

- The Camp Harmony News-Letter carried stories on O'Brien and student relocation on June 12, June 25 and July 10, 1942. Additional issues available in the Puyallup Camp Harmony News-Letter Collection at the Densho Digital Repository. Also see "O'Brien Back at U. of W.; Lauds N.W. Nisei," Minidoka Irrigator, 13 March 1943. Additional issues available in the Minidoka Irrigator Collection at the Densho Digital Repository ↵

- The questionnaires were created by the National Student Relocation Council for all students (high school graduates, transfers and those entering graduate school) wishing to relocate to colleges and universities. Students were required to fill out the questionnaire in triplicate. Questionnaire included as Appendix F in Robert W. O'Brien, "The Changing Role of the College Nisei During the Crisis Period: 1931-1943" (PhD diss., University of Washington, 1945). ↵

- A directory lists relocated students as of June 1943. Directory of American Students of Japanese Ancestry in the Higher Schools, Colleges and Universities of the United States of America... National Japanese American Student Relocation Council with the Collaboration of the National Council of Christian Associations, New York, N.Y, 1943. Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, University of California, Berkeley. ↵

- From Camp to College: The Story of Japanese American Student Relocation. National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, 1945. Japanese American Archival Collection, California State University, Sacramento. ↵

- Provinse, John H. "Relocation of Japanese-American College Students: Acceptance of a Challenge," Higher Education 1, no. 8 (1945):1-4. ↵