Assessing Readiness to Change

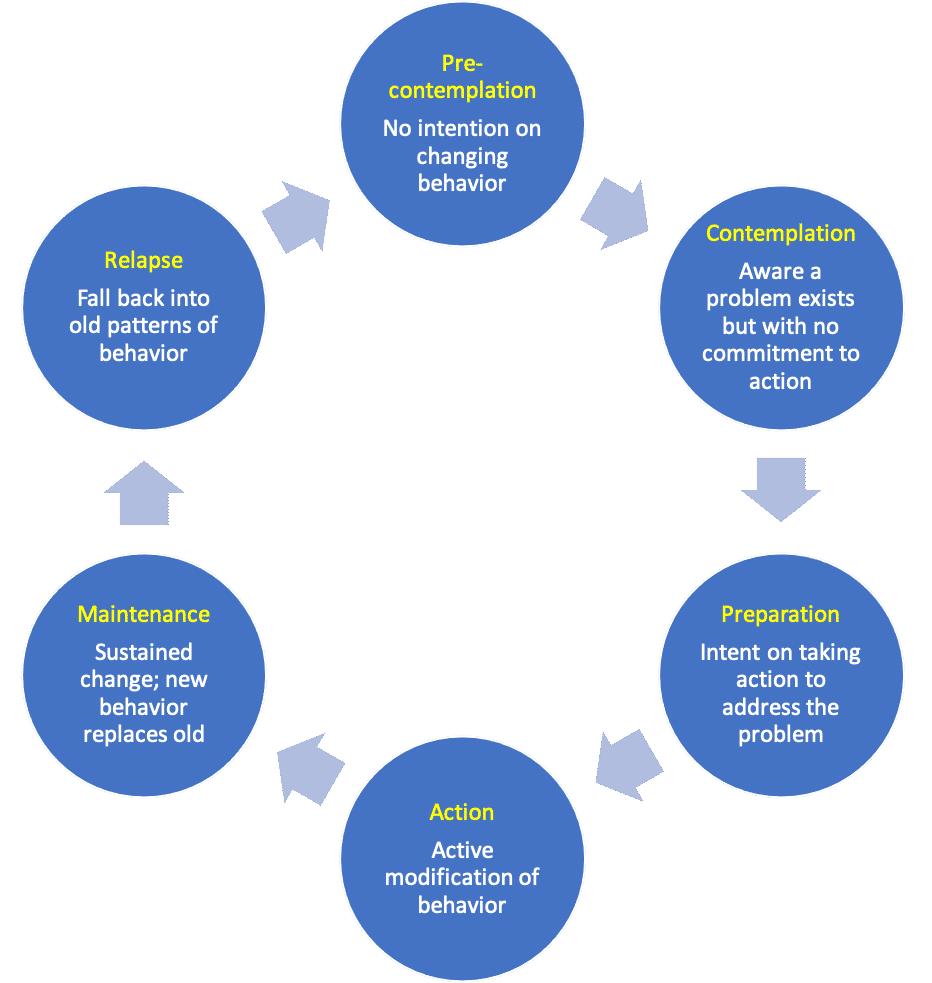

Though the Stages of Change model is based on the people who smoke, clinicians have found it applies in many other situations. Most people do not change any behavior quickly and decisively; they move through a process of change, often toggling back and forth between stages or spending years in one stage before moving quickly through to the next. Relapse is common and returns the person to one of the earlier stages of change.

Cycle of Changed modified from Prochaska & DiClemente, 1992

Different strategies to promote healthy behavior are appropriate at each of these stages – understanding someone’s readiness to change will allow you to meet each person where they are.

Precontemplation

Pre-contemplative patients are not yet considering change and may voice resistance if it’s suggested. Although we may assume they just don’t understand the reasons to change, studies show this usually isn’t the case. While knowledge is necessary, it’s often not enough – competing priorities, lack of resources, culturally inappropriate care, past failures and structural oppression can all act as potent barriers to healthy behavior.

In the pre-contemplation stage, your goal is to open the door to change by building a therapeutic relationship, exploring and honoring your patient’s priorities and values, and – with permission – providing information. It may be tempting to try to “fix the problem” by cheerleading for change, but this unsolicited advice can break down rapport and build resistance.

To assess the stage of change, clinicians may ask if someone is considering a change within the next six months. If the answer is ‘no’, the person is pre-contemplative. Verbal responses or nonverbal cues can also suggest pre-contemplation, as shown in the video below.

How could this clinician respond? An open-ended question like “tell me more” shows respect and receptiveness, as does a reflection like “you have a lot on your plate right now“. Or the physician could offer options to support autonomy and guide the conversation: “Every patient has different priorities; we could talk more about exercise if you want, or we could talk about some simple diet changes or medications. We could also focus on something else today if that makes more sense and come back to this next time.“

Contemplation

Contemplative patients are considering change, usually within the next 6 months. The hallmark of this stage is ambivalence – there are reasons your patient wants to change but they still have reasons to maintain the status quo. Here, your goal is to build intrinsic motivation by eliciting their reasons and ideas for change. This change talk may come out spontaneously or it may be pulled out with the communication techniques described in the next few chapters.

Here’s the same patient with a more contemplative response.

Here, you heard a mix of change talk – statements supporting change – and sustain talk– reasons to maintain the status quo. Sustain talk is normal and absolutely expected at this contemplation stage. If there weren’t reasons to sustain, the patient would already have made the change!

How could this clinician respond? Rather than arguing with sustain talk, the physician should build the patient’s motivation by amplifying the change talk, helping the patient talk themselves into change. A reflection like “you’ve thought about starting a walking routine” would amplify the change talk while an open-ended question like “tell me more about why you’re interested in a walking routine?” might elicit more.

Preparation

In the preparation stage, patients are actively planning to make a change. They are motivated but don’t yet know how to make it happen. Our goal is to support them in developing a specific and realistic plan that honors their individual barriers and resources. Listen to our patient in the preparation phase.

Action

In the action phase, patients have started making the planned changes. This stage requires a considerable amount of time and energy because each action still requires conscious choice or executive control, and the risk of relapse is high. The more times and in more contexts the new behavior is repeated, the more routine it becomes and the less conscious control it requires.

In this stage of change, you can offer affirmations of efficacy, ask about positive impacts of the change (more change talk!), and use open-ended questions to explore barriers and needed resources.

Maintenance

In the maintenance phase, patients are working to prevent relapse and to consolidate the changes they made in the action phase. Solidifying this new habit usually takes about 6 months, but it varies depending on the behavior.

In this stage, physicians should anticipate and explore lapses, and differentiate them from relapse. Even a well-established behavior might lapse when the context changes unexpectedly. These lapses provide information that helps solidify change and build resilience. Eliciting information about how they have overcome other unusual circumstances, affirming commitment and flexibility, and brainstorming options for responding to new challenges helps to solidify the new habit.

For example, our patient may be regularly going to the gym but not anticipate a change in hours over a holiday leading to a missed day. Exploring the lapse with you, he might decide to have a backup physical activity that is more flexible, suggest to his family that they walk together after the main holiday meal, or might strategize a way to get to the gym even when company is over. He might decide holiday weekends will not be exercise days at all!

Supporting our patients’ autonomy, wisdom and resilience gives them the tools to sustain change over the long run.

Relapse

Relapse is common. Our society tends to blame individuals when behavior doesn’t line up with values, but as physicians we know that will power and morality have very little to do with establishing habit. Anticipating the possibility with your patient up front can prevent shame and avoidance if it happens.

Patients must know that we will provide care for them with or without a specific behavior change. If we have laid the groundwork well, both we and they know that the change was not for the physician, and the patient need not be ashamed. Many patients may find themselves “recycling” through the stages of change several times before the change becomes truly established. Normalizing this for patients is helpful.

- “Change involves ups and downs. I’m here for both.”

- “I‘m on your side. I look forward to checking in next month whether this idea works or not.“

Relapse returns a patient to one of the early stages of change: pre-contemplation, contemplation or preparation, as they decide how to respond. But whether a patient decides to try again or not, they can benefit from exploring the journey they’ve taken. When things were going well what did they like about the new behavior? What did they learn about themselves? Acknowledging and reinforcing the successes they did have helps shift the focus away from failure.

The physician must take care to recognize the transition to relapse and use skills appropriate to the new stage. Helping the patient reflect back on their original reasons for change, re-establish goals, and troubleshoot barriers can be helpful.