Adapting the H&P: Children

Children see the doctor for the same reasons as adults: acute problems, chronic conditions, and preventive or ‘well child’ visits, which are much more frequent for kids than adults.

In this workshop, you’ll learn how to adapt your history and exam for children and to gather the history of immunization and growth and development.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that well child visits occur frequently for the first few months of life. The frequency gradually decreases to once a year after age 3. The goals of well child care are to:

- Address parental concerns

- Track growth and development

- Prevent disease and injury

- Identify and address common disorders early

- Promote healthy parenting with Anticipatory Guidance.

The Pediatric Interview

Triadic interviews, which include a caregiver in addition to the patient and clinician, are the norm for pediatric visits. It can be tempting to direct most questions to the caregiver, but always try to include the child. This demonstrates respect, and gives them a sense that they’re part of the process, leading to greater trust and engagement.

At the start of the visit, establish rapport with both the patient and the caregiver. You want to make the child comfortable, but how you do it will vary with their age and personality – stay flexible and observe your preceptors for ideas. Let children check out your instruments or ask them about the characters on their clothes or the toys they brought. You can also engage in age appropriate play, like peek-a-boo for toddlers.

The information a child is able to provide depends on their age, developmental level and communication abilities. Another major variable is how shy they are. A parent may tell you that they speak in complete sentences at home, but you may not get anything out of them because you just met.

With infants and young toddlers, you’ll depend completely on the caregiver for history, which will be based on their observations. Parents can observe changes like fever, crying, weight change, vomiting or decreased appetite. Symptoms like pain, nausea, or fatigue can’t be observed. When parents tell you their infant is in pain, they are interpreting what they have seen – but they are usually right!

Sometime in the second year of life, kids start to develop single words and may be able to answer yes/no questions. By age 5-6, most children can participate in an interview, and should have initial questions asked directly of them. You’ll confirm the history with the parent, or at least look to them to see how they’re reacting – usually they’ll speak up if something doesn’t sound right.

| Toddlers | Ask yes/no questions using kid friendly words |

| Preschoolers | Add more open-ended questions |

| By age 6-8 | Expect reliable information |

| By age 10 | Child is primary source of information |

| At age 11-12 | Part of visit will be done without the parent |

Birth history

Prenatal events, complications of delivery, and especially prematurity can impact children’s long term health. When seeing a new pediatric patient, ask about:

- Gestational age at birth – this is usually reported in weeks.

- Any problems during pregnancy

- Any exposures during pregnancy, to drugs, alcohol or medications

- Any problems in the newborn period

Developmental history

Healthy children develop motor, communication, and social-emotional skills at predictable times and in a predictable sequence as the nervous system matures and myelinates. Development is assessed at each well visit so that disorders such as autism can be identified and addressed as early as possible.

Parents are asked if they have any concerns and a structured screening guide is used to assess whether children are meeting expected milestones. The Survey of Wellbeing of Young Children and the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures are two commonly used screening tools. If any concerns are identified on this initial screen, your preceptor may use more specific tools to assess for specific developmental problems. You’ll learn more about normal childhood development and developmental disorders in the Lifecycle block.

Developmental milestones are often presented in a table like the one below (you don’t need to memorize this!) The milestones in black text are met by 50% to 90% of children, while those in green text are met by over 90%. The absence of protodeclarative pointing at one year and of the ability to say one word at 15 months should trigger specific screening for autism. For a screen reader friendly version of this table, click here.

| AGE | GROSS MOTOR | FINE MOTOR | COGNITIVE COMMUNICATION | SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL |

| 2 months | Head up 45°

Lift head |

Follow past midline

Follow to midline |

Laugh

Vocalize |

Smile spontaneously

Smile responsively |

| 4 months | Roll over

Sit–head steady |

Follow to 180°

Grasp rattle |

Turn to rattling sound

Laugh |

Regard own hand |

| 6 months | Sit–no support

Roll over |

Look for dropped yarn

Reach |

Turn to voice

Turn to rattling sound |

Feed self

Work for toy (out of reach) |

| 9 months | Pull to stand

Stand holding on |

Take 2 cubes

Pass cube (transfer) |

Dada/Mama, nonspecific

Single syllables |

Wave bye-bye

Feed self |

| 1 year | Stand alone

Pull to stand |

Put block in cup

Bang 2 cubes together |

Imitate sounds

Babbling* 1 word |

Protodeclarative pointing*

Wave bye-bye Imitate activities Play pat-a-cake |

| 15 months | Walk backwards

Stoop and recover Walk well |

Scribble

Put block in cup |

1 word*

3 words |

Drink from cup

Wave bye-bye |

| 18 months | Walk up steps

Run Walk backwards |

Dump raisin

Tower of 2 cubes Scribble |

Point to 1+ body parts

6 words 3 words |

Remove garment

Help in house |

| 2 years | Throw ball overhead

Jump up Kick ball forward Walk up steps |

Tower of 6 cubes

Tower of 4 cubes |

Name 1 picture

Combine words Point to 2 pictures |

Put on clothing

Remove garment |

| 2.5 years | Throw ball overhead

Jump up |

Imitate vertical line

Tower of 8 cubes Tower of 6 cubes |

Know 2 actions

Speech half understandable Point to 6 body parts Name 1 picture |

Wash and dry hands

Put on clothing |

| 3 years | Balance on each foot

Broad jump Throw ball overhead |

Thumb wiggle

Imitate vertical line Tower of 8 cubes Tower of 6 cubes |

Speech all understandable

Name 1 color Know 2 adjectives Name 4 pictures |

Name friend

Brush teeth with help |

Social History

In children, the social history is arguably even more important than it is in adults, and focuses on the family rather than the individual. Almost half of American children live in poverty or near poverty, and adverse childhood experiences, such as domestic violence, parental substance use, divorce and death all impact the long term health of children. The I-HELLP pediatric social history assesses child and family needs across five domains: Income, Housing, Education, Legal status, Literacy and Personal safety. In a study of pediatric patients, the use of IHELLP tripled the number of referral to social workers, who were able to connect families with community and legal resources to help address these issues 78% of the time.

| IHELLP Social History Questions. Reproduced with permission from the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership. |

|

|---|---|

| Income | |

| General | Do you ever have trouble making ends meet? |

| Food income | Do you ever have a time when you don’t have enough food? Do you have WIC? Food stamps? |

| Housing | |

| Housing | Is your housing ever a problem for you? |

| Utilities | Do you ever have trouble paying your electric/heat/telephone bill? |

| Education | |

| Appropriate Education Placement | How is your child doing in school? Are they getting the help to learn what they need? |

| Early Childhood Program | Is your child in Head Start, preschool, or early childhood enrichment? |

| Legal Status | |

| Immigration | Do you have questions about your immigration status? Do you need help accessing benefits or services for your family? |

| Literacy | |

| Child Literacy | Do you read to your child every night? |

| Parent Literacy | How happy are you with how you read? |

| Personal Safety | |

| Domestic Violence | Have you ever taken out a restraining order? Do you feel safe in your relationship? |

| General Safety | Do you feel safe in your home? In your neighborhood? |

Immunization history

Immunizations should be reviewed at every visit (including acute visits), with catch-ups offered if necessary. Most electronic health records allow providers to track immunizations and remind them of those that are due. A standard schedule for childhood immunizations is available at this link – it may need to be modified for special situations such as immune deficiency, cancer, or asplenia.

Immunizations are required for licensed childcare and school attendance by state law. The development of herd immunity helps to protect those who cannot receive certain vaccines. As doctors we can emphasize that the more patients that get vaccinated the healthier the community will be.

About one-third of parents are vaccine hesitant, meaning they have questions or concerns about having their child immunized. Most parents will still end up vaccinating despite these concerns, and information provided by a trusted physician can help. Communication strategies that can make a difference include:

- Present vaccination as the default option. A “presumptive” approach that assumes parents will immunize their child has been shown to be more effective than the participatory approach that we use for many other medical decisions. For example, “Jenna is due for hepatitis, rotavirus, and polio vaccines today” rather than “What do you think about vaccines today?”

- Listen to and acknowledge the parent’s concerns in a non-confrontational, non- judgmental, and respectful way.

- Address parent’s specific concerns with a mix of scientific information and personal stories, such as the choice you’ve made for your own children or recommended for family or friends.

- Be honest about adverse affects, providing accurate information along reassurance about the robustness of the vaccine safety system.

Pediatric Physical Exam

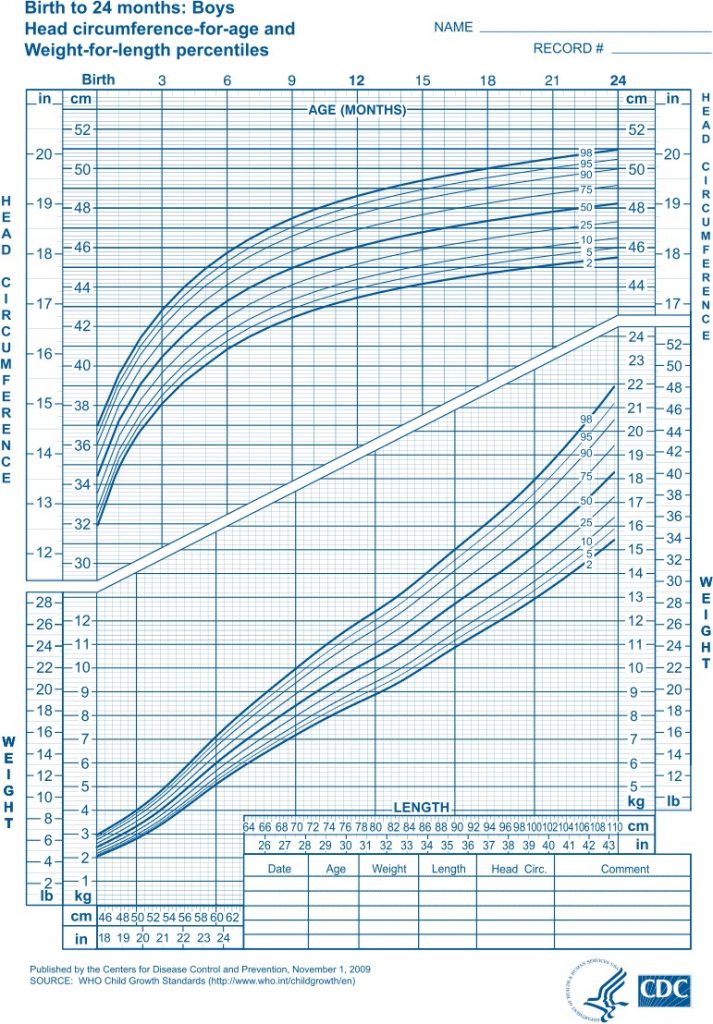

At each well visit, the child is weighed and measured and that data is plotted on a growth chart like the one below. The provider reviews and interprets the findings, paying particular attention to trends over time. Children who are growing normally tend to stay on the same percentile curve for weight, length, and head circumference. Crossing percentiles can be an early sign of abnormal growth that should be addressed. Growth should also be proportional – weight and height should generally increase at a similar rate. You’ll learn more about normal growth, failure to thrive, and how to address childhood obesity in a nonjudgmental way during your Lifecycle block.

Watch this 7 minute video on Vimeo of an experienced pediatrician’s advice on pediatric physical exams

Anticipatory guidance

Anticipatory guidance is the proactive counseling offered at well child visits for health promotion and injury prevention. It addresses common issues and concerns based on the age and developmental stage of the child, with special attention to the prevention of injuries, which are still the most common cause of death in children. For example: most infants learn to roll over at about 4 months, so anticipatory guidance at the two month visit includes keeping a hand on the child when they’re on a high surface like a changing table.

Most practices have standard handouts to give families at each well visit. Providers might highlight or discuss the recommendations of most interest or relevance to a family, and let them review the rest at home. Areas addressed include:

- Feeding, diet, and activity

- Dental care

- What to expect in terms of development

- Safety and injury prevention

- Screen time

References and Resources

CDC Vaccine App available at Vaccine Schedules App | CDC.

The Cribsiders Podcast “Trauma Informed Care in Pediatrics”

Ted Talk “How childhood trauma affects health across a lifetime”