Applied Cardiac Exam

After the Advanced CV exam workshop, you should be able to:

Perform the Immersion Cardiovascular Exam and interpret your findings

Perform hypothesis-driven exam maneuvers

- Measure jugular venous pressure

- Assess the apical impulse

Recognize and interpret these findings on the cardiovascular exam

- Three systolic murmurs:

- innocent a.k.a functional murmur

- aortic stenosis

- mitral regurgitation

- Two diastolic murmurs:

- aortic regurgitation

- mitral stenosis

- Physiologic and abnormal splitting of S2

- S3 and S4

- Edema

- Abnormal pulses

Measure jugular venous pressure

If you suspect abnormal volume status, assess jugular venous pressure. This is demonstrated in the video below and in the workshop.

- Position the head of the bed at 30°-45°. Your patient should be resting comfortably against the bed with the neck relaxed and turned slightly away.

- Identify internal jugular venous pulsations or the conduit of the external jugular vein. If you cannot see them, adjust the head of the bed. Move it up if you suspect volume overload and down if you suspect volume depletion.

- Locate the top of the neck veins, defined as the point where the internal jugular venous pulsations become imperceptible or the conduit of the external jugular disappears

- Measure the vertical distance between the top of the neck veins and the sternal angle.

- Add this distance to 5 cm.

Clinical significance:

- The normal JVP is 5-8 cm of H2O

- Elevated JVP argues strongly that the directly measured central venous pressure (=right atrial pressure) is over 8 cm H2O. The elevated central venous pressure could be caused by left heart disease, primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension, or pulmonic stenosis.

- Flat neck veins with your patient supine correlates with a measured CVP less than 5 cm of H2O, suggesting intravascular volume depletion.

Assess apical impulse

If you suspect ventricular hypertrophy or valvular heart disease, palpate the apical impulse.

The normal apical impulse in the 4th or 5th intercostal space, at or medial to the midclavicular line. It should be a quick tap, about the size of a dime, against the examiner’s hand as the left ventricle contracts. It is palpable in only a third of healthy adults and is more likely to feel it in the partial left lateral decubitus position.

- A laterally displaced apical impulse is a specific but insensitive finding of ventricular enlargement and/or a depressed ejection fraction. If your hypothesis is that these are present, the finding of lateral displacement of the apical impulse supports it. Given the low sensitivity, the absence of lateral displacement doesn’t argue strongly against it.

- An enlarged apical impulse is defined as > 4 cm in the partial left lateral decubitus position and also supports a hypothesis of enlargement of the ventricle.

- A sustained apical impulse lasts longer than normal and indicates pressure or volume overload of the left ventricle.

Murmurs

Identifying murmurs is a skill that you will begin to build in Foundations. The recordings and additional resources in this chapter are a good place to start. A good next step is careful auscultation of a patient’s murmurs with comparison to what your preceptor or an echocardiogram found.

Five characteristics of a murmurs are used to identify its cause and determine the need for an echocardiogram. You should assess and report:

- Grade: from I-VI

- Quality, for example harsh or blowing

- Timing in systole or diastole

- Location where the murmur is heard

- Radiation to other sites such as the carotids or axilla

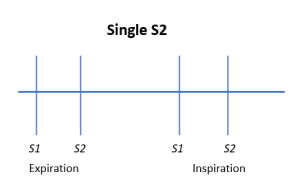

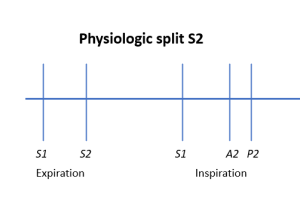

The second heart sound is composed of A2 (aortic valve closure) and P2 (pulmonic valve closure). In healthy people, A2 and P2 are nearly simultaneous during expiration and are heard as a single sound. In inspiration, the negative intrathoracic pressure that pulls air into the chest also increases venous return to the right ventricle. Because more time is needed for this extra blood to cross the pulmonic valve, P2 is delayed. In some healthy people, it may be heard as a separate sound at the LUSB. This is called normal physiologic splitting.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

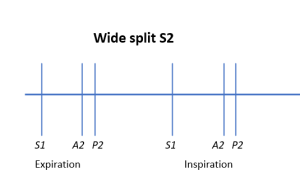

Wide splitting means that A2 and P2 are both audible throughout the respiratory cycle. In atrial septal defect, a L to R shunt increases blood flow across the pulmonic valve during both expiration and inspiration. Because there is no variation with the respiratory cycle in ASD, splitting is both wide and ‘fixed’, or consistent.

Right bundle branch block is a more common cause of wide splitting. Although it can be hard to hear, there is still respiratory variation in RBBB so splitting is wide but NOT fixed.

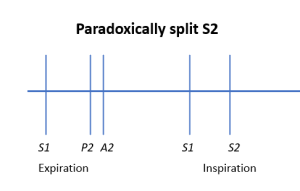

Paradoxical splitting is heard during expiration rather than inspiration. In this case, A2 is delayed and follows P2. Inspiration increases venous return so P2 “catches up” creating a single S2. Left bundle branch block, advanced aortic stenosis and CHF can all cause paradoxical splitting.

S3 and S4

S3 and S4 are low frequency extra sounds best heard with the bell of the stethoscope at the cardiac apex. If you suspect but don’t hear these sounds, re-examine the patient in the left lateral decubitus position.

| S3. “I be-lieve.” |

|

Sudden deceleration of blood flow into the L ventricle in early diastole. | Adults: CHF, valvular disease

Children: may be normal |

| S4. “Be-lieve me.” |

|

Atrial contraction pushing blood into a stiff ventricle in late diastole. | Hypertrophy or fibrosis |

S3 occurs during early diastole and is caused by sudden deceleration of blood flowing rapidly into the left ventricle . In patients over 40, the cause is almost always systolic heart failure or valvular regurgitation. If the L atrium is overfilled, as in mitral regurgitation, high pressure will increase early diastolic filling. If the left ventricle is non-compliant or overfilled, as in heart failure, early diastolic blood flow will decelerate quickly. Both situations can cause an S3.

An S3 may be a normal finding in children and young adults. Their healthy ventricles relax in early diastole to allow very rapid filling, which can cause an S3 even with a normal ventricle.

S4 is heard in late diastole, when atrial contraction pushes blood into the ventricle, and indicates the ventricle is abnormally stiff, due to hypertrophy or fibrosis.

Pericardial rub

A pericardial rub is a high-pitched, scratchy sound caused by pericardial inflammation. A rub is best heard along the lower left sternal border using the diaphragm of the stethoscope with the patient sitting up, leaning forward, and briefly holding the breath.

Edema

The most common causes of bilateral edema are venous stasis disease, congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, drug induced edema, and liver or kidney disease. The most common causes of unilateral edema are deep vein thrombosis, Baker’s cyst and cellulitis.

Assess for pitting edema by pressing on the distal tibia for 2 seconds. If a depression (“pit”) remains, pitting edema is present. Pitting indicates that edema fluid is low protein, as in congestive heart failure, hypoalbuminemia, or pulmonary hypertension. Repeat as needed to define the proximal extent of the edema.

Edema is often graded on a subjective 1-4 scale. Severity can also be documented by describing the proximal extent as well as the presence or absence of weeping or skin ulceration.

Peripheral pulses

Peripheral pulses should be assessed if you suspect cardiovascular disease.

- Femoral pulses are palpated just below the inguinal ligament, midway between the pubic tubercle and and the anterior superior iliac spine

- Posterior tibialis pulses are palpated just behind the medical malleolus

- Dorsalis pedis pulses are palpated on the mid-dorsum of the foot, just lateral to the extensor tendon of the big toe.

Many healthy people lack either the posterior tibialis or the dorsalis pedis pulse, but if one is anatomically absent the other is enlarges to make up the difference. The absence of both pedal pulses supports a diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease.

Resources & references

University of Michigan Professional Skills Builder. Heart Sounds & Murmurs library. The murmur examples in this chapter come from this collection, which is open access. Check it out if you’d like to hear more.

Access Medicine Multimedia: Auscultation Classroom. Examples of common and uncommon murmurs.

Evidence Based Physical Diagnosis, 5th edition. McGee SR. The definitive summary of the evidence for different physical exam maneuvers by a now retired (sniff) University of Washington Professor of Internal Medicine. Full text is available via Clinical Key on the Health Sciences Library Care Provider Toolkit.

- Inspection of the Neck Veins

- Palpation of the Heart

- Auscultation of the Heart: General Principles

- The First and Second Heart Sounds

- The Third and Fourth Heart Sounds

- Heart Murmurs: General Principles

patient rolled 45 degrees to the left, to bring the apex of the heart closest to the chest wall.

I = faint. II = easily heard. III = loud. IV = thrill and heard with stethoscope on chest. V = thrill and heard with stethoscope edge on chest, VI = thrill and heard with stethoscope off chest