Applied Abdominal exam

After the Advanced Abdominal Exam workshop, you should be able to:

- Perform the Immersion Abdominal Exam and interpret your findings

- Recognize common findings on the abdominal exam

- Perform hypothesis driven exam maneuvers:

- If you suspect renovascular hypertension: Listen for renal artery bruits.

- If you suspect appendicitis: Assess for McBurney’s point tenderness

- If you suspect cholecystitis: Assess for Murphy’s sign

- If you suspect ascites: Test for a fluid wave and shifting dullness

- If you suspect aortic aneurysm: Assess the diameter of the abdominal aorta using palpation.

Findings you should recognize & interpret

Auscultation

Absent bowel sounds suggest peritonitis, complete bowel obstruction, or ileus. You must listen for 2 minutes to say that bowel sounds are completely absent.

Tinkling bowel sounds suggest partial small bowel obstruction. They are high pitched and occur in rushes. .

Percussion

Percussion tenderness suggests peritonitis. Gentle percussion causes pain, either at the site of tenderness to palpation or elsewhere in the abdomen.

Palpation

Rigidity suggests peritoneal inflammation. Rigidity is INVOLUNTARY contraction of the abdominal musculature in response to peritoneal inflammation.

Guarding on the other hand is VOLUNTARY contraction of the abdominal musculature due to tenderness, fear, cold hands, or anxiety.

Firm or nodular liver edge suggests cirrhosis. The liver edge normally lies under the rib cage at the R midclavicular line. A firm, cirrhotic liver is more likely to be palpable than a normal liver. If the liver edge is palpated, feel carefully for clues to cirrhosis. The cirrhotic liver is firmer than normal, and may have palpable irregularity or nodules.

Splenomegaly. The normal spleen is not palpable. If it is palpable, it is enlarged. Common causes of splenomegaly are cirrhosis, hematologic malignancies, and infectious diseases.

Hypothesis-Driven Exam Maneuvers

Suspected renovascular hypertension: Assess for bruits

Who: Patients with severe, difficult to control hypertension

How: Listen with the diaphragm of the stethoscope ~ 2 cm above the umbilicus, both in the midline and laterally. Bruits heard over the flanks are uncommon but highly suggestive of the diagnosis. In the example below, you’ll hear bruits plus bowel sounds.

Clinical significance: The presence of a bruit supports the diagnosis of renovascular hypertension but the absence decreases the probability only slightly (LR 0.6)

Bruits in this location can also be heard in up to 20% of healthy people under 40, likely caused by flow through the celiac axis. If you hear a bruit in someone without severe hypertension, no further work up is needed.

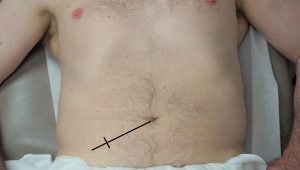

Suspected appendicitis: Assess McBurney’s point tenderness

Who: Patients with RLQ or midabdominal pain +/- nausea & vomiting

How: The anatomic location of the appendix in most adults falls 1/3 of the distance from the right anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus – palpate at this specific point.

Clinical significance: McBurney’s point tenderness supports appendicitis more strongly (LR 3.6) than general RLQ tenderness. Absence of McBurney’s point tenderness argues against appendicitis. (LR 0.4)

Suspected cholecystitis: Assess for Murphy’s sign

Who: Patients with RUQ or epigastric pain, fever, and/or nausea & vomiting

How: Palpate just below the right costal margin in the midclavicular line and observe as your patient breathes in. Murphy’s sign is a pause in inspiration as the tender and inflamed gallbladder hits the examiner’s fingers.

Clinical significance: Murphy’s sign supports cholecystitis (LR 3.2) but its absence decreases the likelihood slightly (LR 0.6). Murphy’s sign can also be observed on ultrasound.

Suspected ascites: Assess for fluid wave & shifting dullness

Who: Patients with abdominal distention

Fluid wave. Place one hand against one side of the abdomen as you percuss the opposite side with your other hand. A positive result is a tap against your hand caused by a wave of ascitic fluid set in motion by percussion. To decrease motion of the soft tissue, which can give a false positive result, an assistant or the patient holds the edge of their hand firmly in the midline.

Clinical significance: The presence of a fluid wave increases the probability that ascites is present (LR 5.0 ) while the absence decreases it (LR 0.5)

Assess for shifting dullness: Starting at the umbilicus, percuss from anterior to posterior, marking the border between resonance (air filled bowel) and dullness (ascites). Ask your patient to roll over partway, and again percuss and mark the border between resonance and dullness. A positive result is a shift in the border as the ascites fluid shifts when your patient rolls over.

Screening for aortic aneurysm

Who: Males > 65 with a history of smoking OR known family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm.

How: Press gently inward in the epigastric region slightly left of the midline to identify aortic pulsations. Now place one hand on each side of the aorta, and measure its diameter. Subtract the estimated thickness of soft tissue.

Clinical significance: The normal aorta is < 3 cm. An aneurysm is > 3 cm and expansile, pushing the hands apart. The larger the aneurysm, the more likely it is to be detected on exam.

Exam is much less accurate in those with an abdominal girth > 100 cm/40 inches. Medicare covers one time ultrasound screening for patients at risk based on criteria above.

References & resources

- Renal artery bruit for educational purposes, posted on YouTube.

- Evidence Based Physical Diagnosis.

slowed GI motility caused by opioids, recent surgery, or medical illness.