6 Chapter 6: Reclaiming Food Systems: Indigenous Food Sovereignty and the Path to Food Justice

By Jasmine Dalida

Abstract:

This research paper examines the complex dimensions of Indigenous communities seeking to reclaim their food sovereignty. It explores the historical and systematic injustices that have led to food insecurity in Native communities, emphasizing the importance of land rights, economic and regulatory barriers, traditional ecological knowledge, community empowerment, and policy changes. The paper argues that food justice, when rooted in Indigenous knowledge and self-determination, provides a powerful framework for dismantling systemic barriers to food sovereignty and fostering equitable, resilient food systems.

Introduction

Indigenous communities face ongoing challenges in accessing nutritious and culturally appropriate foods due to historical and present injustices. Addressing the root causes of food insecurity, such as land dispossession and economic barriers, is essential for achieving food sovereignty. Food justice, when rooted in Indigenous knowledge and self-determination, offers a path toward healing from the past, amplifying Indigenous voices, empowering communities, and transforming food systems to ensure equity and cultural preservation. By prioritizing Indigenous leadership and advocating for policy changes that support their rights and foodways, we can create a food system that truly honors Indigenous food sovereignty and promotes food justice for all.

Historical Context: Land Dispossession and Food Insecurity

Understanding the history of food insecurity is essential for addressing today’s challenges. The foundation of Indigenous food sovereignty lies in reclaiming land rights. It emphasizes that restoring land rights is essential for ending food insecurity in Native communities, highlighting that one in four Native Americans lack reliable access to healthy foods (Jernigan, 2020, p. 4). As Jernigan (2020, p. 4) explains, the dispossession of land has had a long-lasting effect on food security in Native communities, disrupting traditional agricultural practices and severing the connection between people and their food sources. Examining how communities responded to hunger in the past can inform contemporary food justice movements, as Potorti (2017) points out, providing valuable lessons for building resilience and self-sufficiency. Building on this land is more than just a resource; it is a sacred gift integral to cultural identity and community well-being. This connects agroecology and land stewardship to Indigenous identity and practices, highlighting the importance of traditional farming methods that align with environmental stewardship (Price et al., 2022, p. 3).

These practices are not just about food production but about maintaining a reciprocal relationship with the land, ensuring its health and productivity for future generations. The land represents a connection to ancestors, culture, and traditional ways of life; its restoration is important for revitalizing Indigenous food systems and cultural practices. The forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands, the suppression of traditional foodways, and the imposition of government-controlled food systems have all contributed to high rates of food insecurity in Native communities today, creating a legacy of dependence and vulnerability.

The forced removal of Native people from their traditional homelands in the 19th century disrupted Indigenous food systems and diets.

For example, the White Earth Land Recovery Project (WELRP) in Minnesota works to restore land to the Anishaable people, revitalizing traditional food systems and cultural practices. This reclamation is not just about land but about restoring a way of life. Government policies, such as the Dawes Act and boarding schools, played a significant role in disrupting Indigenous food systems and cultural practices, further eroding Indigenous control over their food and resources.

Figure 1. WELRP Benjamin Velani (2023)

Community Empowerment: Iniatives Economic Barriers

Community-led initiatives are critical in combating food insecurity and promoting self sufficiency. Potorti (2017) examines historical community survival initiatives, highlighting the importance of community-based solutions. Jernigan (2020) emphasized that community control over food systems is essential for self-determination and resilience. Community gardens, farmers’ markets, and food banks exemplify community led initiatives that improve food access and promote self sufficiency, The Zuni Tribe in New Mexico revitalized traditional farming practices through community based education and resource sharing (Velani, B. 2023, April 4). These initiatives not only provide food but also strengthen community bonds and cultural identity.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Certification Systems and Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS)

AspectTraditional Certification SystemParticipatory Guarantee Systems (PGS)

| Aspect | Traditional Certification System | Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) |

| Costs | High | Lower |

| Verification | External | Community-Based |

| Community Involvement | Limited | High |

| Approach | Standardized | Culturally Relevant |

However, even with strong community initiatives, even with land, Indigenous communities face significant economic and regulatory challenges in accessing and controlling their food systems. Systematic barriers, as noted by Potorti (2017), hinder community empowerment and equitable food access. Government food programs often fall short in meeting the specific needs of Native Communities. The costs associated with entering mainstream markets and complying with regulations can be prohibitive for small scale Indigenous farmers. Alternative certification systems, such as Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS), offer a more accessible and culturally relevant approach, emphasizing community involvement and trust based verification. These systems can reduce reliance on external inputs and promote local control.

Cultural Identity: Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Foodways

Community-led initiatives are critical in combating food insecurity and promoting self-sufficiency. Potorti (2017) examines historical community survival initiatives, highlighting the importance of community-based solutions that arise from within the community itself, addressing their specific needs and circumstances. Jernigan (2020) emphasizes that community control over food systems is essential for self-determination and resilience, allowing Indigenous communities to define their own food priorities and strategies. Community gardens, farmers’ markets, and food banks exemplify community-led initiatives that improve food access and promote self-sufficiency, providing direct sources of nutritious foods and fostering local economic activity. These initiatives often draw upon Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), which, according to Snively and Corsiglia (2000), is a cumulative body of knowledge and beliefs, handed down through generations through cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment.

The Zuni Tribe in New Mexico revitalized traditional farming practices through community-based education and resource sharing (Potorti, 2017), demonstrating the power of local knowledge and collaboration in building sustainable food systems. These initiatives not only provide food but also strengthen community bonds and cultural identity, reinforcing a sense of collective responsibility and shared well-being.

However, even with strong community initiatives and access to land, Indigenous communities face significant economic and regulatory challenges in accessing and controlling their food systems. Systematic barriers, as noted by Potorti (2017), hinder community empowerment and equitable food access, limiting the reach and impact of local efforts. Government food programs often fall short in meeting the specific needs of Native Communities, often designed with a one-size-fits-all approach that fails to account for cultural preferences and local contexts. The costs associated with entering mainstream markets and complying with regulations can be prohibitive for small-scale Indigenous farmers, creating an uneven playing field that favors large-scale agricultural operations. To counter these barriers, alternative certification systems, such as Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS), offer a more accessible and culturally relevant approach, emphasizing community involvement and trust-based verification. These systems reduce reliance on external inputs and promote local control, empowering Indigenous communities to participate in food production and distribution on their own terms, fostering economic independence and self-reliance.

Policy and Advocacy: Achieving Food Justice

Food justice is an integral component of achieving food sovereignty. Cadieux and Slocum (2015) define food justice as empowering communities to demand equity in food systems. Linking food sovereignty and rights to food justice in Native communities, as noted by Jernigan (2020), ensures that Indigenous communities have the power to make their own choices about food and health. Food justice recognizes that food insecurity is often rooted in systemic inequalities, such as racism, poverty, and lack of access to resources. By addressing these underlying issues, food justice movements can create more equitable and sustainable food systems. This includes advocating for fair labor practices, access to healthy food in underserved communities, and policies that support Indigenous food sovereignty. To truly achieve food justice and support Indigenous food sovereignty, urgent policy changes are needed to support Indigenous food sovereignty. Jernigan (2020) advocates for policies that prioritize land rights and food sovereignty. Policies supporting Indigenous agricultural practices, as discussed by Price et al. (2022), can promote sustainable agriculture and community well-being. Policy changes should incorporate measures to protect Indigenous land rights, promote TEK, and support Indigenous-led food initiatives.

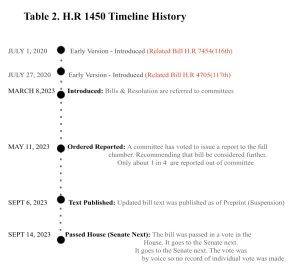

Table 2. H.R 1450 Timeline History

For example, the Farm Bill- H.R. 1450 – Treating Tribes and Counties as Good Neighbor Act 118th Congress (2023 -2024) could be amended to include provisions that specifically address the needs of Indigenous farmers and ranchers. Additionally, policies should support Indigenous control over natural resources, such as water and seeds.

Conclusion

Indigenous communities still struggle to get good, healthy, and culturally important foods because of unfair things that happened in the past and continue today. To fix this, we must deal with the root causes of food insecurity, like taking away land and creating economic problems. Food sovereignty can only be achieved when we address these issues. Food justice, when it’s truly based on Indigenous knowledge, leadership, and the right to make their own choices, offers a way to heal from the past. It lets Indigenous people speak for themselves, helps communities take control of their food systems, and changes those systems to be fair, protect culture, and support self-determination. We need to put Indigenous people in charge and push for policy changes that support their rights, food traditions, and goals. If we do this, we can create a food system that respects Indigenous food sovereignty and makes sure everyone has food justice, so Indigenous communities can thrive in their own way.

References

Sampson, D., Cely-Santos, M., Gemmill-Herren, B., Babin, N., Bernhart, A., Kerr, R. B., Blesh, J., Bowness, E., Feldman, M., Gonçalves, A. L., James, D., Kerssen, T., Klassen, S., Wezel, A., & Wittman, H. (2021). Food Sovereignty and Rights-Based Approaches Strengthen Food Security and Nutrition Across the Globe: A Systematic review. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.686492

Price, M. J., Latta, A., Spring, A., Temmer, J., Johnston, C., Chicot, L., Jumbo, J., & Leishman, M. (2022). Agroecology in the North: Centering Indigenous food sovereignty and land stewardship in agriculture “frontiers.” Agriculture and Human Values, 39(4), 1191–1206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10312-7

Cadieux, K., & Slocum, R. (2015). What does it mean to do food justice? Journal of Political Ecology, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.2458/v22i1.21076

Jernigan, V. B. B. (n.d.). Ending food insecurity in Native communities means restoring land rights, handing back control. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/ending-food-insecurity-in-native-communities-means-restoring-land-rights-handing-back-control-158858

Snively, G., & Corsiglia, J. (2000, January 10). Discovering Indigenous Science: Implications for Science Education. [PDF Document]. Retrieved from https://blogs.nwic.edu/briansblog/files/2011/02/Discovering-Indigenous-TEK-Implications-for-Science.pdf

Velani, B. (2023, April 4). White Earth Land Recovery Project builds community connectedness and Sustainability. wcif.org. https://wcif.org/blog/environment/white-earth-land-recovery-pr/

Pogphotoarchives. (n.d.). Palace of the Governors Photo Archives: Photo. Tumblr. https://pogphotoarchives.tumblr.com/image/159429057227

H.R.1450 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Treating tribes … (n.d.-d). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/1450/text

Media Attributions

- IMG_6130

- IMG_6131

- IMG_6132