4-4 Second Language Acquisition

Next, we’ll talk specifically about second language acquisition.

There are various factors that contribute to the development of language in children who are multilingual learners, such as individual differences in language skills (higher receptive than expressive language skills), age of exposure, or the quantity and quality of exposure.

Quantity and Quality of Exposure

The quantity and quality of exposure to language may cause children who are multilingual learners to experience a time lag between understanding a concept in two languages and having the words in both languages to express it. For example, children may feel and understand emotions in all the languages they are experiencing, but they may only have the words to express their emotions in the language(s) they hear at home. They need to learn the words to express their emotions in all the languages they hear.

As educators, it is important to foster an environment that supports children’s language development and sustenance.

As you learned previously, children can acquire languages either simultaneously or sequentially in relationship to the development of their home language. Understanding how young children learn more than one language is continuing to develop. Thirty or more years ago, literature discussion focused on English immersion as the only way for a child to learn English when they entered school knowing a language other than English.

Recent research highlights, especially for young children, that continuing to develop a home language helps them learn English because, ultimately, language is language.

Age of Exposure

Researchers continue to discover the amazing abilities of infants to recognize and use sounds and sound combinations in different languages. It also appears that most languages have rule-based systems that dictate which sounds are used, how they are put together to form and change words and word meanings, and how the words are combined to form questions and comments. Different languages follow different rules, but the systems of one language create the foundation in the developing brain to recognize and use the systems of a different language.

Think about learning to drive. You get the basics of how to start a car, push the accelerator to go, and use the brake to stop. So, even when you get in a different car, you can still drive it. It is similar with dual language development; the brain recognizes the patterns and rules of sounds, words, and sentences in all the different languages to which it is being exposed. This is especially true in young brains!

Current research also explains that children can and do learn more than one language through prenatal and ongoing exposure to different languages from effective language users.

Study data from prenatal and preverbal infants suggests that they have innate capacities that allow them to learn two languages without significant costs to the development of either language, provided they receive consistent and adequate exposure to both languages on a continuous basis (Paradis, Genesse, & Crago 2011).

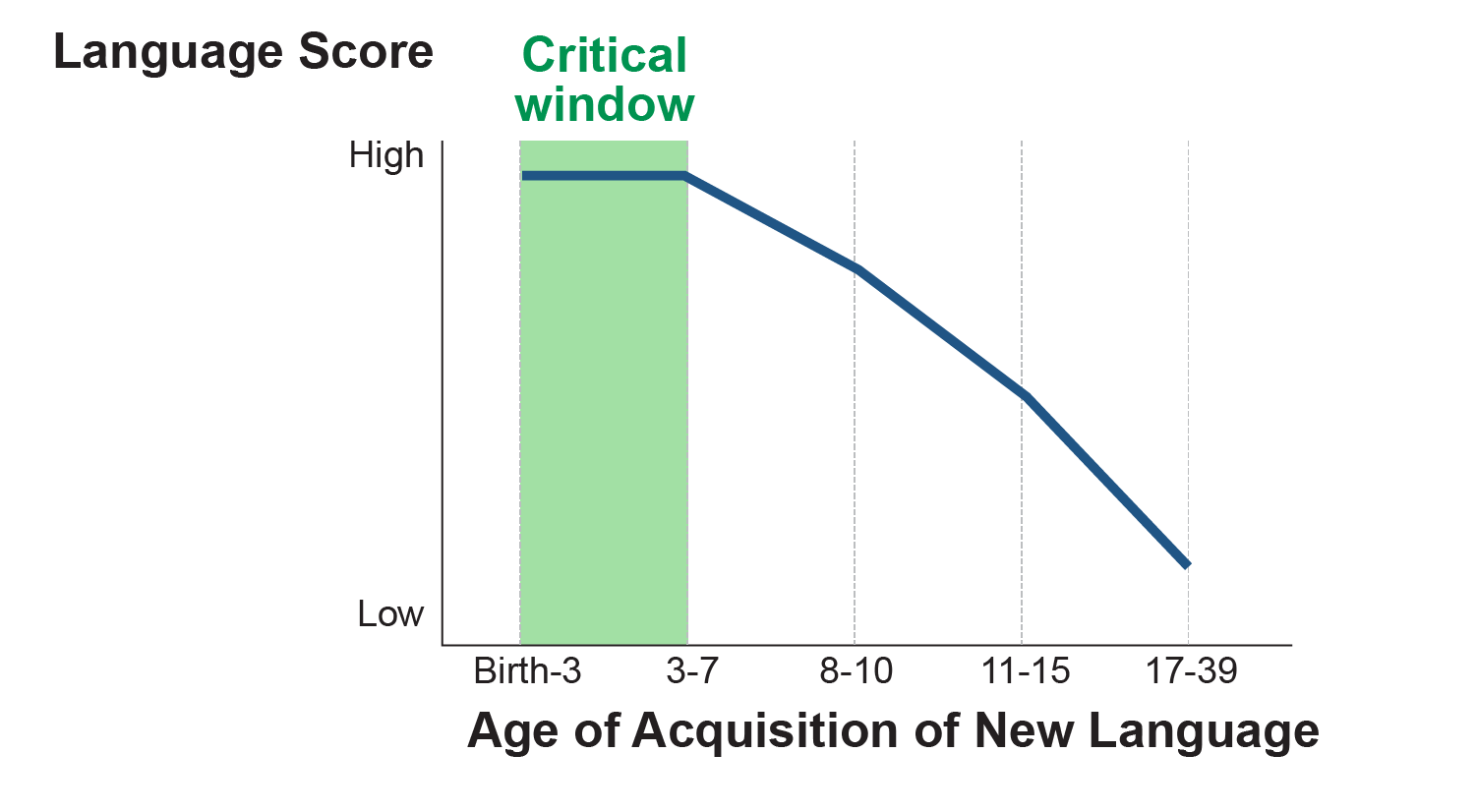

Find your current age on this chart. How easy would it be for you to learn more than one language?

How does this chart inform educators’ work with young children?

Stages of Sequential Language Development

According to recent research by Dr. Jonathan O’Muircheartaigh and colleagues in The Journal of Neuroscience (2013), “the brain has a critical window for language development” between the ages of two and four, which may explain why young children are so good at learning two or more languages. Environmental influences are the most powerful during a child’s early years when the brain’s wiring grows as it processes new vocabulary in all the languages that the child hears.”

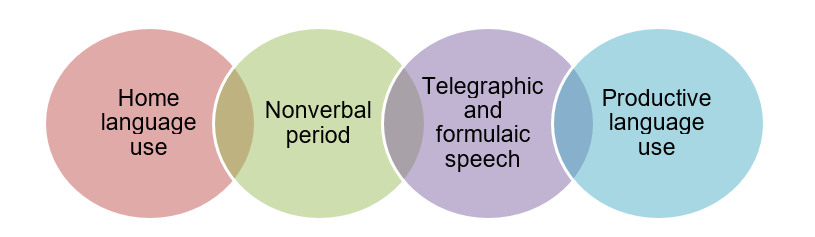

This diagram illustrates stages within sequential language development. Notice how each stage overlaps with the next. In the nonverbal period, we can acknowledge that a child who is a multilingual learner is practicing receptive language development of their second language. When a child reaches the telegraphic and formulaic speech phase, they are using two-word phrases (e.g. “Go now.” or “Mommy up.”). Finally, productive language use can be considered fluency in language.

Theories of language acquisition and proficiency

In addition to the stages of second language development, it is important to consider different theories surrounding how children best acquire a second language.

Two major theories have been developed to explain second language acquisition and proficiency:

- “Time-on-task” theory

- “Linguistic interdependence” hypothesis

People use these theories to develop and advocate for different types of instructional approaches for children who are multilingual learners. We’ll be learning more about instructional approaches later in the course. For now, let’s talk about each of the two major theories.

Time-on-Task

The “Time-on-task” theory developed by Rossell and Baker (1996) states that children’s amount of exposure in one language will determine not only the level of vocabulary the child might develop in that language, but also the level of overall proficiency. In other words, the more time you spend learning a certain language, the greater proficiency you will attain in that language.

The theory has provided support for the development of English-only programs, such as the structured English immersion (SEI) program (MacSwan et al., 2017). In this model, instruction is only provided in English.

Linguistic Interdependence Hypothesis

Next is the linguistic interdependence hypothesis. It suggests that the development of the child’s second language is dependent on or is facilitated by the development of his first language. This hypothesis suggests that the development of the child’s second language (L2) is dependent on or is facilitated by the development of his first language (L1).

Specifically, Cummins (1981) states that language development is composed of a set of underlying cognitive and academic processes that are universal across languages, such as story comprehension, understanding story structure, and basic reading processes. Therefore, these underlying processes facilitate the transfer of academic and school-related knowledge from one language to another.

People have used this hypothesis to advocate for bilingual instructional approaches, such as bilingual education programs (literacy instruction in L1) or dual language programs (subject instruction in both languages).

More recently, McSwan and colleagues (2017) point out that “the concern with the linguistic interdependence hypothesis is the embedded assumption that language and language-related academic content-matter are not distinct” (p. 223). To address this concern, MacSwan and Rolstad (2005) created a variation of the linguistic interdependence hypothesis known as transfer theory.

Transfer Theory

Transfer theory is a variation of the Linguistic Interdependence Hypothesis. It suggests that conceptual knowledge (being able to understand concepts) is accessed or can be learned in any language that the child speaks. Conceptual knowledge is distinct from linguistic knowledge, which develops as a natural result of speaking a language on an everyday basis. Therefore, academic instruction in any language helps develop conceptual knowledge that children can later transfer into L2.

Or stated in the context of an example, Cummins’ hypothesis suggests that knowing how to read in L1 helps a child learn how to read in L2. He implies that conceptual knowledge of reading is tied to language development. Instead, MacSwan and Rolstad contend that children can learn how to read in any language, and this process is separate from language development. In other words, children don’t have to know how to read in L1 in order to transfer that knowledge to L2.

References

Byers-Heinlein, K., Burns, T. C., & Weker, J.F. (2010). The roots of bilingualism in newborns. Psychological Science, 21 (3), 343-348.

Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In California State Department of Education (Ed.), Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework. Sacramento, CA: Office of Bilingual Bicultural Education, California State Department of Education.

Kuhl, P. K., & Ramirez, N. F. (2016). Bilingual language learning in children. Institute of Learning. Seattle, WA. [PDF]

K., Burns, T. C., & Weker, J.F. (2010). The roots of bilingualism in newborns. Psychological Science, 21 (3), 343-348.

MacSwan, J., Thompson, M. S., Rolstad, K., McAlister, K., & Lobo, G. (2017). Three theories of the effects of language education programs: An empirical evaluation of bilingual and English-only policies. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 218-240.

MacSwan, J., & Rolstad, K. (2005). Modularity and the facilitation effect: Psychological mechanisms of transfer in bilingual students. Hispanic Journal of the Behavioral Sciences, 27(2), 224–243.

O’Muircheartaigh, J., Dean, D.C., Dirks, H., Waskiewicz, N., Lehman, K., Jerskey, B., & Deoni, S. (2013, Oct. 9). Interactions between white matter asymmetry and language during neurodevelopment. Journal of Neuroscience 33(41). https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.146

Paradis, J., Genesse, F., Crago, M. (2011). Dual Language Development & Disorders, Second Edition. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Rossell, C. H., & Baker, K. (1996). The educational effectiveness of bilingual education. Research in the Teaching of English, 30(1), 7–74.

Cite this Source:

EarlyEdU Alliance (Publisher). (2019). Second Language Acquisition. Supporting Multilingual Learners Course Book. University of Washington. [UW Pressbooks]