Main Body

2 Reflections On Numerous Readings

Story Maps and Disability Studies

Aldinger, J. M.M. (2018). Story Maps and Disability Studies: A Digital Blueprint for Teaching Community Engagement. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 12(1), 59–70.

My first foray into fall DFW reading is an article that synthesizes ideas from my favorite spring quarter class (community engagement), the digital platform I worked with summer quarter (Story Maps), and concepts relevant to my fall quarter fieldwork (disability and accessibility). J. M.M. Aldinger, a professor at Lynchburg College in Virginia, insightfully discusses the revision of a major assignment in an undergraduate writing course that, through the use of mapping, specifically ArcGIS’s Story Maps, catalyzed students to not only think more critically, but additionally engaged their nascent sense of community-based activism.

Notably, Aldinger briefly establishes connections between spatial theory (largely Foucault) and disability studies (Tobin Siebers’ Disability Theory, for instance). In particular, his article introduced me to the concept of a “deep map,” which J. Corrigan, D. J. Bodenhamer, and T. M. Harris claim “‘is a finely detailed, multimedia depiction of a place and the people, animals, and objects that exist within it and are thus inseparable from the contours and rhythms of everyday life'” (qtd in Aldinger p. 62). In theory, this exemplary visualization of critical cartography holds great potential for learners to forge connections between space, place, and all objects within these domains. From a pedagogical standpoint, I also enjoyed Aldinger’s reflections on his assignment revisions and his concrete examples of student work. The author’s culminating reflections offer empirical insight into undergraduate learning, too.

Issues, though, that arose in my mind, include the following: Aldinger discusses ways that students used Story Maps to see and think through specific accessibility issues (for instance, mobility impaired persons’ navigation of campus spaces), yet he doesn’t discuss accessibility issues in relation to the online platforms his class used. For instance, did students fill in the appropriate boxes to ensure that screen-readers could “read” all the content of their maps? Were there any low-vision students in the class who had difficulty using Story Maps? Additionally, while the author is generally attuned to the ways that critical cartography/geography (or the spatial humanities, his preferred term) can help us problem-solve access and accessibility issues in a holistic or more interconnected manner, I wish he had addressed, in a little more detail, what feminist-vegetarian C.J. Adams might call the “absent referent.” I saw the “absent referent” thusly: even though GIS might “make mapping new,” these digital platforms can’t entirely be severed from the roles maps, mapping, and cartography have served as agents of power concentrated in the hands of politicians, governments, and empires.

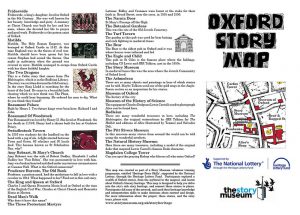

Image

Oxford Story Map side 2″ by lunaman is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Feminist Podcasts

Richardson, S., & Green, H. (2018). Talking women/women talking: The feminist potential of podcasting for modernist studies. Feminist Modernist Studies, 1(3), 282–293.

I greatly enjoyed this thought-provoking reading, which introduced me to a variety of issues in the digital humanities. In particular, the authors’ discussion of “the privilege of proximity,” wherein scholars, due to their nearness to archives, Special Collections, and manuscript repositories are able to mine the past directly through an array of artifacts (p. 282). Although a seemingly “natural” aspect of academic research, this access truly is a privilege, which the majority of graduate students and faculty, for a variety of reasons including location, time, money, gender, race, etc may never have the chance to connect with. The university I worked at in San Antonio did not have a library for the first three years I was teaching there, so access even to “non-rare” materials was considered a privilege.

As the authors enumerate the ways in which archival materials have become more accessible through digitization, they shift to their article’s focus: the podcast as a ways to extend academic conversations in ways that may help scholars surmount difficulties, including the inherent problems/difficulties of conferencing, and assist undergraduates and graduates in taking a more active part in scholarship. As Richardson and Green maintain, they don’t believe podcasts should replace static forms of scholarship, such as the academic paper, but they do offer potent alternatives for engagement and access (p. 289).

A point that especially resonated with my experiences (and my past students’ experiences) is the writers’ discussion of the “other” voice: “In its spoken form, the podcast has the potential to position accent at the heart of our scholarship, destabilizing the idea that there are proper ways of speaking about, or ‘doing’, modernist scholarship” (p. 286). Richardson and Green go on to discuss the non-binary voices of creators and speakers on the Modernist Podcast and the ways in which those voices implicitly challenge the status quo. Unfortunately, while the authors recognize that podcasts may be inaccessible for many d/Deaf listeners, the only alternative they propose is including a transcript with audio file. As a user who identifies as hard-of-hearing, I found this particular paragraph rather disappointing, a single red mark on an otherwise invigorating article.

Image

“Radio” by spwelton is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Justice and the University

Grande, S. (2018). Refusing the University. In Toward What Justice?: Describing Diverse Dreams of Justice in Education. Edited by E. Tuck and W. Yang. New York: Routledge. pp. 47-65.

Grande’s “Refusing the University” offers insightful meditations on the university as an institution whose structure and politics relies too firmly on colonial discourses and practices. Consequently, the university’s primary subjects—students and faculty (“staff” are not discussed in this essay, which I’ll come back to)—all too often reproduce academia’s penchant for reconciling injustices rather than seeking productive ways to “refuse” these injustices. Notably, the statements I’ve issued do not fully capture Grande’s central nexus of ideas, in part because, as she’s made me aware, academics don’t always distinguish amongst some of the most potent nuances of colonialisms. Nor do scholars consistently address crucial points she raises, such as antiblack racism is not synonymous with the colonial oppression that American Indians and Indigenous populations more broadly endure.

Grande lays the foundation for her article by proffering her central interests in investigating “the promissory relationship between Black radical and critical Indigenous frameworks as both help to imagine life beyond the settler state and its attendant universities. In doing so, . . . [she is] aware of the tensions and antagonisms between Black and Native experience as produced through the distinct but related frameworks of white supremacy and settler colonialism” (p. 50). Drawing on the work of P. Wolfe (1999, 2006), she offers a definition for settler colonialism, by writing, “In contrast to other forms of colonialism, ‘settler colonies were not primarily established to extract surplus value from Indigenous labor’ . . . but rather were premised upon the removal of Indigenous peoples from land as a precondition of settlement. . . . [As a result] a settler colonial framework represents a particular set of relations, one that originates with the theft of Indigenous land and the ‘remove to replace’ logics that enable that theft” (p. 52).

Note: Much of my past teaching has focused on 20th century British literature. Thus, discussing colonialism and its long-lasting impact on peoples, languages, and social structures, especially in African nations and Ireland, is by no means unfamiliar. Because I haven’t yet had the chance to delve deeply into Indigenous knowledge systems, histories, and political practices, this essay serves as an introduction into these vital topics. I great appreciate Grande’s underscoring of “settler colonialism” throughout her essay, particularly because “land” is essential to her own argument about the vitality of refusal within the academy.

To this end, Grande next discusses the problematic power imbalances relating to theories and discourses of recognition. Deploying G. Couthard’s (2014) work, she writes, “he exposes the limits of recognition-based politics for restructuring Indigenous-state relations, as it leaves intact the state’s role as arbiter and therefore ultimate reproduces the very configurations of colonial power that Native peoples seek to transcend” (p. 54). I couldn’t agree more with this position. It is vile when a US state or the national government suddenly decides to “recognize” tribal claims, not because the white power-mongers at the heart of the state are responsible for the theft and erasure of Native lands, waters, and peoples, but also because, if accepted, the power imbalances are reproduced. Grande sagely shows how these imbalances and the reproduction of them play out in an institutional context since, as she claims, “liberal theories of justice . . . ultimately sustain relations of institutional oppression” (p. 55).

In the final section of her essay Grande demonstrates that institutional struggles for recognition within the university—by students of color, by women and minority faculty—are very often commendable. And while proffering a politics of refusal, she also acknowledges the perils of refusal, such as lack of tenure and increased marginalization within academic settings. Yet she affirms that we must “work[] simultaneously beyond resistance and through the enactment of refusal—as fugitive, abolitionist, and Indigenous, sovereign subjects” (p. 60). Notably, Grande concludes by offering “strategies for refusing the university.” For instance, she writes, “We need to commit to collectivity—to staging a refusal of the individualist promise project of the settler state and its attendant institutions” (p. 61). She additionally calls for a “commit[ment] to recirprocity—the kind that is primarily about being answerable to those communities we claim as our own and those we claim to serve” (p. 61). Finally, she maintains, “we need to commit to mutuality” which “is about the development of social relations not contingent upon the imperatives of capital—that refuses exploitation at the same time as it radically asserts connection, particularly to land” (p. 61).

I find Grande’s strategies very tantalizing, especially since I’m often frustrated by the lack of concrete actions we might take to begin combating injustices. Though Grande discusses, in passing, academic models of resistance and refusal in the forms of Mississippi Freedom Schools and the Undercommoning (p. 60), I would’ve liked to hear more. I want to know what these past models look like, and I want more details about how we can enact her various commitments; I want to know what we’re supposed to do when we encounter resistance to our refusals of and within the university. Furthermore, since Grande emphasizes the collective and the mutual so greatly in her strategies, I want to know how the university’s staff—so completely undervalued in academic hierarchies—can join with faculty and students to refuse. Staff doesn’t just include the librarians, but also the academic advisors, custodial teams, and everyone else who ensures that the system runs and is thus instrumental to the project of refusal. Finally, I want to know why the editors of this book, who have the best of intentions for collective social justice projects, decided to publish with Routledge, a company that consistently peddles some of the most expensive hardback books in academic publishing. I acknowledge that Routledge published this book simultaneously in hardback and paperback formats–a decision I applaud–but it feels like a different press might’ve been more in keeping with the book’s politics and that collective strike against academic hierarchies (including tenure via publication).

Image

Apparently, there’s no link in my notes for this photograph, but there are similar photos on Pexels, including this “red building with clock tower” image from Pixabay.

Is All Technology is Assistive?

Hendren, S. (2018). All Technology is Assistive: Six Design Rules on Disability. Making Things and Drawing Boundaries : Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Edited by Jentery Sayers. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. pp. 139-145.

Hendren, whose oeuvre resides at the intersection of engineering, design, and art, tackles a timely topic in her short essay. She begins by deferring to G. Pullin’s Design Meets Disability (2009), using his monograph to make the salient point that “disability concerns are . . . an overlooked source of rich aesthetic ideas, with relevance and impact for design beyond their immediate starting point” (p. 139). In short, design, whether it’s for furniture or walkways, should always consider issues of disability and ablebodiedness in tangent with each other. Hendren offers a few reasons why creators should do so; perhaps her most convincing explanation revolves around the idea that as bodies age, people who have lived ablebodied lives may find themselves at other ends of the spectrum (p. 140).

I couldn’t agree more with Hendren’s perceptive ideas, especially when she tackles the United States’ “obsession” with bodily norms, which far too often demonize those of us who fall outside of socially and historically constructed categories of “normality.” But I found myself frustrated with her article when she declares (echoing her titular claim) that “All technology is assistive technology” (p. 140) and then contends that our cell phones and eyeglasses (amongst other technologies) “are assisting . . . [us] in multiple registers” (p. 140). There are two immediate reasons I felt aggravated. First, cell phones can be but are not always assistive; for myself, they wreck havoc on the eyes and concentration. Additionally, the claim Hendren uses to structure her article seemingly echoes the “We’re all the same under our skin” statements which rendered multiculturalism in the late 80s and throughout the 90s a seriously problematic discourse. If we’re all the same, we are continually urged to forget and/or erase those significant differences that structure our lived experiences, our identities, and our hopes for creating more equitable futures. Nonetheless, I acknowledge that Hendren may have written this article with zero intention of eliciting these types of responses from her readers.

Hendren’s six design rules are generally sound: “invisibility is overrated” (p. 141), “rethink the default bodily experience,” “consider fine gradations of qualitative change,” “uncouple media technologies from their diagnostic contexts” (p. 142), “design for one,” “let the tools you make ask questions, no just solve problems” (p. 143). In particular, the final directive is essential to all “good” value-sensitive design and a design ethos willing to tackle “wicked problems,” which are so complex in their scope that raising questions often seems like an ideal way to begin addressing them. “Design for one” is perhaps the only rule I can take issue with as it seems starkly opposed to the multiplicities that explicitly and implicitly structure her other guidelines; moreover, the example she provides to illuminate this directive isn’t fully explained. Overall, the brief article is insightful, and Hendren’s problematic central claim raises offers fodder for a spirited response and perhaps the rethinking or nuancing of the phrase “assistive technology.”

Image

“1958 Zenith Hearing Aid Advertisement Readers Digest October 1958” by SenseiAlan is licensed under CC BY 2.0

White Feminism and the Academic Library

Watson, Megan. (2017). White Feminism and Distributions of Power in Academic Libraries. Topographies of Whiteness: Mapping Whiteness in Library and Information Science. Edited by Gina Schlesselman-Tarango. Sacramento: Library Juicy Press. pp. 143-174.

Watson’s essay “analyzes academic libraries’ practices through the lens of white feminism[s], a brand of feminist praxis defined by the exclusion of the bodies and concerns of women of color.” She then “explore[s] the ways our institutions’ grounding white feminist thinking directs the flow of power and influence . . .” (p. 145). Towards the end of her essay she “offer[s] an alternative theoretical approach and related strategies designed to inspire deeper, self-critical reflection and identify new paths toward a truly transformative model of social justice” (pp. 145-45). The initial theoretical overview she provides is helpful for readers who have not had the opportunity to interrogate the whiteness of first and second wave feminisms or the limitations of third wave feminisms, particularly as constructed by white feminists who, Watson right notes, may recognize the many gaps in earlier iterations of feminist agendas (social class, race, culture, disability, etc), but have no real investment in anything more of an acknowledgment of them in the here and now. Likewise, the overview identifies another insidious change in 21st century feminisms, “the influence of neoliberalism” and the anti-collectiveness/individualization that can accompany these discourses (pp. 150-151).

In the next portion of essay, Watson identifies several sites within the context of academic librarianship where white feminisms overtly structure daily work and relations. She contends, “White feminist thinking is readily apparent in the LIS literature around gender equity and leadership, reflecting and affecting the ways power is understood within the field” (p. 153). In the service of the wielding of power, she draws attention to the ways “Academic libraries and librarians expect their leaders to exemplify (or at least conform to) the dominant culture, asking leadership candidates to effectively and imperceptibly perform whiteness” (p. 155). As a result, women of color who resist the pressure to perform whiteness may be further marginalized and devalued, while white women who assuredly perform will be commended and even promoted.

Though most of the theoretical overview was familiar to me and the issues Watson raised in terms of white feminisms exerting an extremely negative influence on women of color and white women within academic librarianship contexts were, likewise, not new, I’m only one reader of many. All of the information she offers is vital to articulate, to make visible; otherwise, our field will not change. In the third section of her essay, the “alternative theoretical approach” Watson offers a means “to resist and reject white feminism’s hegemony . . . black feminism” (159). I applaud her move to shift the focus to Black feminisms and to recognize that Black feminisms will help white feminisms dismantle a great many of its assumptions. However, a questions arose in my mind at this point in the reading: Why not Black, Indigenous, and Latinx feminisms?

My question was not answered. Though Watson does a fine job of surveying Black feminisms and helping us see how these theories and practices can shift constructions of power, assist in collaboration, and ultimately help us alter spaces we work in, I was left wondering. Will other readers raise similar questions? Will they explore the works of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx feminists and seek differences and intersections amongst them? Will they wonder why Watson (and so many other writers) still persist in writing “feminism” when the concept is a multiplicity (feminisms)?

Image

Photo by Elijah Hail on Unsplash

Closed Captioning in the College Classroom

Jae, H. (2019). The effectiveness of closed caption videos in classrooms: objective versus subjective assessments. Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, vol. 22, pp. 1-9.

Jae’s analysis of closed captioned videos in college classrooms builds on the work of other scholars who have explored the pedagogical potential of captioning for students of all ages within the following scholastic contexts: concentration, anxiety reduction, disability, ELL learning, as well as memory/recall (p. 3). After concisely surveying this wealth of literature, the author briefly delves into the American Disability Act (1990), and discusses ways in which teachers can ensure classroom videos are captioned to ensure compliance. Subsequently, Jae investigates the use of closed captioned videos in “in two International [college] Marketing classes” of 120 students each (5). Only one of the two courses used the captioned videos, and end results show that the undergraduates exposed to the captioning were able to demonstrate their knowledge of more “complex and abstract” information than the students who were not exposed to captioning (p. 5). At the end of the article, Jae underscores notable limitations in the results of this study, particularly the fact that the “sample focused on students whose first language was English,” and there were only “limited number[s] of International and hearing disabled students” (p. 6).

This is article is relatively brief, and since I’m unfamiliar with the journal, it’s not clear whether this piece is a published conference proceeding or just a short social sciences publication with the express purpose of beginning a narrower conversation about captioning within higher education. Regardless, the article would benefit from additional context concerning Universal Design principles as well as some consideration about the challenges captioning can create for both instructors and students (p. 6). For instance, not all instructors can rely on DRS offices to provide captioning (at all or in a timely manner)–the article more than implies they they can. Likewise, captioning can pose issues for some students, particularly if the words are mildly inaccurate or too fast. Nonetheless, I hope that Jae can return to this publication in the future as the article has all the makings of an insightful, effective longer work.

Image

Wikimedia Commons, WGBH, 1980.

Thinking Universal Design Alongside Disability and Digital Humanities

Williams, G. H. (2012). Disability, Universal Design, and the Digital Humanities. From Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 202-212.

Wu, X. (2010). Universal Design for Learning: A Collaborative Framework for Designing Inclusive Curriculum. Inquiry in Education, vol 1, issue 2, n.p.

I read these informative articles back-to-back, and while both are slightly “old” within the context of academic publishing, they raise relevant issues for accessibility within the classroom and academic more formally (and broadly) speaking. Williams and Wu both provide clear definitions and strong overviews of Universal Design. The former writer, though, channels this information into a DH context while the latter considers UD in relation to collaborative teaching.

I particularly enjoyed Williams’ discussion of DH’s untranslatability between computers, iPads, and cell phones, which has bearing on accessibility issues. Williams is also well aware of the socioeconomic implications of assistive technologies ($$) and isn’t afraid to discuss issues of cost-prohibitiveness at appropriate points in the article. Furthermore, the writer makes an important distinction in his discussion of UD by carefully deferring to R. Mace (the architect originator of UD): “To embrace accessibility is to focus design efforts on people who are disabled, ensuring that all barriers have been removed. To embrace universal design, by contrast, is to focus ‘not specifically on people with disabilities, but all people’ (Mace)” (p. 204). In Wu’s article, I was thrilled to see a very careful enumeration of UD principles in relation to “inclusive teaching;” in particular, the author’s two page chart linking principles to classroom guidelines helped me envision UD in action.

Naturally, I had a few quibbles with both articles. The problematic statement addressed in S. Hendren’s article, “All technology is assistive” made an appearance early on in Williams’ piece (p. 204), and there were turns of phrase throughout the essay that could’ve been more inclusive so as to surmount us (able-bodied people) vs. them (disabled people) distinctions. Furthermore, Williams never explained why non-white populations–specifically African American and Hispanic populations–are more likely to use cell phones than computers or why disabled people “tend to be older, to have lower incomes, and to have less education than non disabled adults” (p. 206). I’d love to know whether or not these statements continue to hold water in 2019/2020. In tangent with the issue I raised about the feminist podcasting article, Williams also seems to see the only alternatives for hearing-impaired users in cyberspace to revolve around closed captioning and transcripts. More creative solutions are never conceived, nor is the extreme physical strain that can result from overly relying on one’s eyes when one’s ears are compromised, ever addressed.

Wu’s article frustrated me because the main mode of collaboration discussed rested firmly on teachers (who teach special needs and non-special needs students), rather than on students and teachers. It infuriates me when researchers (and teachers) assume that students themselves don’t have some of the best educational solutions and/or they don’t even consider consulting the very populations they’re seeking to serve. Though Wu briefly addresses the need for other stakeholders to weigh in on UD instructional design methods–“[c]ollaboration may involve people besides teachers and students, such as parents and other school personnel who are part of the students’ educational experience”–there isn’t much discussion of why or how this act might meaningfully occur. Additionally, while I greatly appreciate the emphasis on diversity and inclusion, Wu also never explains how students with disabilities who are not part of the white majority, may or may not fair with UD instructional principles. In short, there’s a little too much faith in UD as a problem-solving process; admittedly, this stance makes some sense given the article’s publication date.

In the end, I’m grateful after reading the articles for more grounding/knowledge/information about accessibility, but I’m nowhere closer to creative, accessible solutions that can be fluidly implemented in library teaching sessions.

Image

“a11ylogo500” by Terrill Thompson is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Feedback/Errata