Introduction

Dr. Heather Price, North Seattle College

Our students learn about climate change in many of our classes and then they are hungry for what to do with that knowledge and how to connect it within their careers and communities. Climate touches and belongs in every subject we teach, and it’s not enough for us to only teach the issues and facts. That’s like a doctor giving a patient test results, but not the tools to heal and repair. This is where civic and community engagement comes in.

Climate Justice Across the Curriculum workshops seek to build bridges between disciplines and faculty as they incorporate climate justice and civic engagement into their courses in ways that empower students. During these workshops faculty come together to support each other as they weave climate justice and civic engagement into one or more of their classes.

Each chapter of this book contains curriculum developed by an instructor in one of the Climate Justice Across the Curriculum workshops at the University of Washington Seattle held in the winter of 2021 and 2022. These winter workshops at UW Seattle are adaptations of the well-established Climate Justice curriculum workshops at Bellevue College and North Seattle College which grew from the Curriculum for the Bioregion at Western Washington University.

The following section is adapted from a book chapter by Sonya Remmington-Doucette and Heather Price in, An Existential Toolkit for Climate Justice Educators (2022).

Why weave climate justice and civic engagement into our courses?

Civic and community engagement involves collaboration with others to improve your community and can be done through political or non-political means and by anyone no matter age or citizenship status. It can involve a wide range of actions such as posting on social media, talking with a friend about a climate justice issue, volunteering with a community climate justice organization, testifying before city council, or organizing a protest. In our classrooms, civic and community engagement can also mean instilling in our students the knowledge, skill, responsibility, efficacy, commitment, and values which are all important qualities of engaged citizens (Wang and Jackson, 2005).

There is no one definition for climate justice. A working definition is that it is centered on taking action for a just transition to a sustainable future by recognizing the disproportionate effects of climate disruption on marginalized groups and future generations. It is concerned with inequities that arise from climate disruption that occur between generations (inter-generational equity) and those that occur among people living today (intra-generational equity). Viewing climate change through a justice “lens” means asking questions such as: Who has power and access to resources, and who doesn’t? As a result, who feels the disproportionate effects of things like climate change, and who will weather climate changes better as a result of their privileged position in society? It also means taking action to address these inequities and disrupt systems of oppression through community and civic engagement.

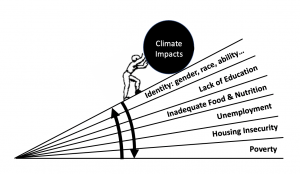

Figure 1: Intra-generational climate justice wedges. Wedges represent factors affecting an individual or community’s capacity to mitigate or adapt to climate impacts represented by the boulder. Adapted from Making Partners: Intersectoral Action for Health 1988 Proceedings and outcomes of a WHO Joint Working Group on Intersectoral Action for Health. The Netherlands.

Climate justice includes both intergenerational and intragenerational aspects (Kanbur, 2015; Stapleton et al., 2018). Intergenerational climate justice refers to the impact of one generation on another. For instance, the impact of each generation’s resource use on future generations who are not yet here, and do not yet have a voice. Intragenerational climate justice refers to impacts within a generation.

Everyone living today plays a role in intragenerational climate justice. For instance, the lifestyles of the richest 0.54% of global population, about 42 million people, emit more greenhouse gas emissions – due to flying, driving, big homes, and consumption – than the poorest half of the global population, which is over 3.6 billion people (Otto et al., 2019). Various factors such as education, gender, race, ability, employment, food & nutrition, healthcare, and housing, all impact a person or a community’s ability to contend with climate impacts that are happening right now (Figure 1). Because of historical oppression and colonization from rich countries and peoples, those most affected by intra-generational climate injustice are people in the global south, and communities of color, particularly Indigenous, Black, and Latinx, living in rich countries.

An example of an intra-generational climate justice issue is particulate matter (PM 2.5) air pollution that comes from climate-exacerbated wildfires and smoke in the Western U.S. and from the burning and extraction of fossil fuels like methane (so-called natural) gas, oil, and coal. Burning fossil fuels is now recognized to be responsible for an estimated 1 in 5 deaths worldwide, and over 950 deaths each day in the US (Vohra et al., 2021). A person or community’s ability to contend with PM2.5 air pollution depends on many factors listed in Figure 1. This is also where the benefits of community engagement are apparent. For instance, in Seattle, a BIPOC led community organization, Got Green, set up a trading space for people in the community to donate or pick up air filters and box fans during the 2020 smoke season, at a local coffee house, the Station Cafe. The organization utilized the power of social media to advertise this to the community on Instagram. In this way, community engagement, in the form of mutual aid, can help individuals or a community to overcome some of these disparities. This local example has also been used as an example of civic engagement and climate justice in the authors’ STEM major college-level chemistry classes.

Description of Climate Justice Faculty Curriculum

The Climate Justice with Civic Engagement Across the Curriculum project for faculty development was adapted from a well-established local sustainability curriculum infusion model developed by the Curriculum for the Bioregion Initiative under the leadership of Jean McGregor (Washington Center for Improving the Quality of Undergraduate Education, 2020). This program at UW, NSC, and BC came about from grassroots efforts of faculty and staff presenting a proposal to administrators for funding, and included support from the offices of Instruction, Sustainability, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, and Student Leadership. At UW and NSC, a student TA was also employed to provide a student perspective and voice. The curriculum offers in-person and online learning communities, summer institutes, workshops, and other modalities that provide interdisciplinary faculty cohorts with the financial support and time to co-create and weave climate justice and civic engagement into their courses. Financial support, paying faculty for their time in lesson development and implementation, is important especially for community college faculty who are tethered to very high teaching loads with little time “to ponder, rethink, relearn, and redesign courses” (Hiser, 2020, p.1).

It’s also important to protect meeting times for collaborative work and discussion so that most lesson creation happens in-community. Three to four online workshop meeting days, 1.5 to 2 hours each, take place with one to two weeks between each meeting day. This spacing allows time for faculty to reflect on their readings and discussions, and to design their curriculum. It’s also important to keep these faculty institutes and workshops relatively small, or to allow for online or in person breakout spaces where faculty feel comfortable discussing the challenges of incorporating issues of justice, equity, and community action into their courses. This is especially important for STEM faculty for whom incorporating such issues is often a new skill, and is also why it’s important to pair STEM faculty with humanities and arts faculty for whom this way of teaching is the norm. Faculty benefit from working with small groups of 8-16 colleagues at the same institution, learning from each other and building bridges across disciplines.

An online learning system, in our case Canvas, is used to organize faculty into quarterly learning community groups of 8-16 faculty, where they can find and share resources on climate justice case studies and civic and community engagement. A public facing website is also available to point passersby to the curriculum repositories and upcoming opportunities to participate.

Brief overview of the five components of the existing CJC interdisciplinary faculty PD model. Including description of activities that can occur in a one day (2 hour) workshop, or over a 3-4 day (1.5-2 hour/day) faculty institute

- Introduction to Climate Justice, and Community and Civic Engagement (C&CE)

- Getting participants into the “mindset” to create lessons that integrate climate justice and C&CE requires baseline knowledge of climate justice and C&CE. Therefore, the first step is for faculty to learn about and discuss climate justice and C&CE. Through readings and group discussions they learn how climate justice and C&CE are different from, but related to, climate science and service learning, respectively.

- Interdisciplinary Faculty Group Brainstorm to Create a Draft Module.

- The next step is for faculty to work together in an interdisciplinary group brainstorm to come up with an outline for a module (lesson, assignment, lab, and/or activity) for their chosen class. Faculty first identify basic disciplinary concepts and skills specific to their discipline and chosen class. Next, they connect these concepts and skills to climate justice and C&CE. Faculty create and share their draft lessons using a visual that triangulates their disciplinary concepts and skills with the climate justice issue(s) and the C&CE they will weave into their courses. Throughout the brainstorm exercise, faculty give and receive feedback as they share-out their lesson ideas and drafts.

- Experience a Climate Justice Lesson and Collaborative Reflection

- The facilitator walks through or shares an example lesson that includes a climate justice issue and C&CE, and illustrates a variety of pedagogical elements (lectures, activities, videos, discussion). Participants continue to brainstorm and work on their lesson drafts in small interdisciplinary groups as they reflect on the pedagogical elements they may adopt, determine resources and information still required, and how to situate the lesson in their course based on students’ prior knowledge.

- Faculty Present Draft Module with Feedback and Reflection

- Each faculty presents a short overview of their lesson to the interdisciplinary faculty group, including an overview of all lesson materials (i.e. learning outcomes, Powerpoint presentations, videos, grading rubrics, activity sheets, assignments). After each presentation, the group offers feedback. Faculty are also asked to offer their reflections and insights on how different disciplines connect climate justice and C&CE to their disciplinary content.

- Faculty Submit their Module to a Curriculum Repository

- Faculty implement their Climate Justice Lessons. One other faculty person from the interdisciplinary group observes their lesson. After lesson implementation, faculty and students complete surveys. Faculty make final lesson revisions and create a lesson plan. Finally, lessons are uploaded to a public Curriculum Repository.

Some Additional Resources

The Curriculum for the Bioregion initiative’s Sustainability Courses Faculty Learning Community spent several meetings in 2012 brainstorming big ideas in sustainability that would be relevant to college and university learners. Robert Turner, a faculty member at University of Washington Bothell, created this website to collect our work; there are some excellent resources here: http://faculty.washington.edu/rturner1/Sustainability/Big_Ideas01.htm

Teaching-and-learning activity ideas can be found in the Curriculum for the Bioregion Curriculum Collection, which is housed at the Science Education Resource Center (SERC) at Carleton College. Visit the Curriculum for the Bioregion website (http://bioregion.evergreen.edu) and click on Curriculum Collection.

More details and information about the Climate Justice Across the Curriculum projects at Bellevue College and North Seattle College can be found at http://www.bellevue.edu/climatejustice and https://northseattle.edu/climate-justice

“Curriculum for the Bioregion” Initiative, Washington Center for Improving the Quality of Undergraduate Education, The Evergreen State College. http://bioregion.evergreen.edu

References

Cho, “Climate Justice in BC: Lessons for Transformation. Climate Justice Project,” 2014. [Online]. Available: https://teachclimatejustice.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/full_teachclimatejusticedotca.pdf. [Accessed 10 June 2020].

Hiser, “Community Colleges Responding to the Climate Crisis. National Council for Science and the Environment,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncseglobal.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/2020%20Edition%20Introduction-Community%20Colleges%20Responding%20to%20the%20Climate%20Crisis.pdf. [Accessed 29 July 2020].

Y. Wang and G. Jackson, “Forms and dimensions of civic involvement,” Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, vol. 11, no. 39, pp. 39-48, 2005.

Washington Center for Improving the Quality of Undergraduate Education, “Curriculum for the Bioregion Initiative: Building Concepts of Sustainability into Undergraduate Curriculum,” [Online]. Available: https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.wwu.edu/dist/a/3038/files/2019/04/Integrating-Sustainability_Overview-1.pdf. [Accessed 27 May 2020].

Clayton, S., Manning, C. M., Krygsman, K., & Speiser, M. (2017). Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica.

Media Attributions

- CJPressbookFig1