2 Propaganda and Nazi Germany

Sean Heans

“People were to expect the National-Socialist movement [to] intervene in the economy and in general cultural affairs, and that includes film.” – Joseph Goebbels

Propaganda and Nazi Germany

Film has been used as a tool for many disciplines. Starting from the early scientific attempts to record movement by Muybridge, to the filming or regular life by Lumiere in what is called the cinema of attractions, to the infinite ways in which we use moving images today in microbiology, astronomy, and just the common place ways for us to record our own lives through our camera phones. Contrasting the aforementioned uses, there is perhaps one use for film that is most infamous of all, propaganda. This essay will describe the origin and evolution of propaganda leading up to what is perhaps the most egregious use of propaganda, its use by Nazi Germany. We will also look at some issues of propaganda, particularly its effectiveness and its comparison to what we might today call propaganda. Perhaps, propaganda never went away such as in the way we are bombarded with political Facebook post or political YouTube ads.

Origin and Evolution of Propaganda leading up to the Nazis

Propaganda has a deliberate component; one can test this by asking “Can propaganda be made accidentally?” probably not. Reeves quotes Terrance Quaker’s description of propaganda as “The deliberate attempt by the few to influence the attitudes and behaviour of the many by the manipulation of symbolic communication”. Propaganda has been used over the centuries for many purposes, it started with what may be considered a noble pursuit, then it gained a pejorative connotation (Reeves 11) but in spite of that, Nazi Germany would recognize the value of propaganda, particularly in the film medium. This section describes the origins and evolution of propaganda and attempts to ascertain how the Nazis adopted it and used it.

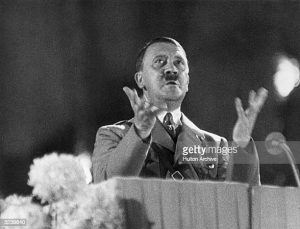

It is likely that most people think of Nazi Germany when they hear the word “propaganda”, but the word propaganda is much older than the Nazis and began, almost forebodingly, as a way to spread religion. The word propaganda derives from a decision by Pope Gregory XV, who in 1622 issued the Papal Bull Inscrutabili Divinae establishing the Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith), with a mission of winning back those who had been lost to the Church in the Reformation (Reeves 11). The similarities between a preacher and Hitler are hard to ignore.

Credit: CNS Credit: Keystone/Getty Images

However, Hitler was not the first leader to be filmed, that title goes to Russian Tsar Nicholas II (Reeves 1). According to Reeves, the Tsar showed great interest in film and even built his own cinema in his palace, but it seems he failed to recognize the power of film to influence people. Reeves quotes the Tsar saying: “I consider that the cinema is an empty, totally useless, and even harmful form of entertainment.” Four years later, the Tsar would lose his reign to the Bolsheviks might have been the first to considered propaganda central to their new regime (Reeves 3).

It would still be a while before the time would come for Nazi propaganda and if you have a preconceived notion that propaganda is used only by what the allies perceived as “the bad guys”, you would be wrong. The next use of propaganda was by a soon to be member of the allied forces, the British government. During the First World War, the British government had, for the first time, engaged in a systematic and sustained campaign of official film propaganda (Reeves 5). However, it seems that by this time, propaganda was already frowned upon, for when that war ended, the British abandoned all the new mechanisms for official film propaganda (Reeves 5). It is after that that the Nazis would finally pick up propaganda and run with it as we will see in the next section.

Goebbels and Nazi Propaganda

The Nazis were quick to recognize the value of film propaganda and implement it, however, implementing it took various steps and even when Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister of Propaganda, had incredible control over Germany’s filmmaking, propaganda was still implemented with some amount of caution. This section will describe how the Nazis put in place their propaganda system and how it was implemented.

As one may imagine by all the existing Nazi footage, Hitler and the National Socialists in Germany, gave propaganda in general, and film propaganda in particular, a very high priority (Reeves 5). But before the Nazis could implement their film propaganda machine, they would have to gain control of the German film industry. Their chance would come in 1933 when the Reichstag (home of the German parliament) burned down. The Nazis, using fear, gained enough leverage to push a legal framework that would allow them to pass laws without the approval from either house of parliament (“Cinema and Filmmakers Under the Nazis | Filmportal.De”). This would be the first step the Nazis would take in order to take over the film industry. Using their newfound authority, the Nazis would buy up companies in the film industry turning filmmaking into a state-run enterprise, and a tool of the National-Socialist leadership (“Cinema and Filmmakers Under the Nazis | Filmportal.De”). With the film industry under control, it would be up to Joseph Goebbels to implement the strategy from film propaganda production.

Credit Getty Images

Goebbels wanted to deliver that radical transformation in ideas, attitudes and beliefs for which the Bolsheviks had been striving in the Soviet Union (Reeves 10) and Goebbels himself, would be the main influencing force in German film for the years to come, he would use various techniques to aggrandize Hitler and vilify the Jewish people to achieve his goals, but at the same time, understood that there must be some nuance.

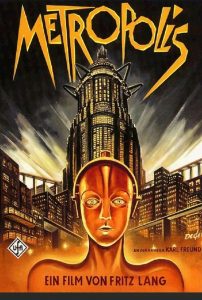

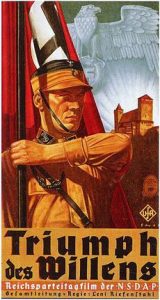

Perhaps the most well-known Nazi propaganda film is “Triumph of the Will” directed by Leni Riefenstahl, a film which “glorified Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party” (Facing History And Ourselves). “When compared to one another, Triumph des Willens is easily seen as a propaganda reinvention of Metropolis” (Boland). In both films, the main heroes, Hitler and Maria, are filmed at low angles surrounded by a uniform crown. This is done to distinguish them and show them as different from the rest, putting them up on a pedestal and making them special. Both films looked to inspire the viewer, in the Triumph of the will, this was also done by marching in an orderly manner, this “order was considered a means to an end; the parade march evolved out of patriotic feelings and in turn aroused them in soldiers and loyal subjects” (Kracauer 54). Another thing worth mentioning is that Maria was a true embodiment of someone that wanted to liberate people from an oppressive society, opposite of that was Hitlers imagined mission of liberation from foreign forces. This plagiarism leaves much to be desired. It is perhaps well explained by the idea of “the cult of the movie star”, from an essay called “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in which a reproduction “preserves not the unique aura of the person but the “spell of the personality,” the phony spell of a commodity” (Benjamin). Is it possible that Triumph of the Will really didn’t show the aura of a hero? But instead, it delivers a mere spell of personality? Is it possible for a crow to differentiate between those?

Fritz Lang Leni Riefenstahl

Another technique that Goebbels used was to produce derogatory film about minorities and, preposterously, call them factual. One such film was “The Eternal Jew” directed by Fritz Hippler. Among the most egregious scenes in this film, Jews are compared to disease carrying vermin. This film was praised as a documentary but contained sufficient inaccuracies that parts of it had to be omitted from the version shown in other countries (Facing History And Ourselves). Perhaps the blatant use of this propaganda will be hard to reconcile with the fact in the next paragraph that ideally, governments usually try to conceal their role in wartime propaganda (Reeves 6).

Nazis weren’t the only ones using propaganda in World War Two. Just as Nazis demonized their enemies, so too did their enemies demonize them hiding the fact that Goebbels was a shrewd man. “Nazi Germany was not in reality the monolithic, totalitarian society described in the propaganda of its enemies” (Reeves 10). Although, as mentioned earlier, Goebbels did have great influence over the German film industry, he exerted this influence in a cautious way. Goebbels, at least throughout the years of peace, it did rather less to disturb the established German economic and social structure (Reeves 10). So, Goebbels wasn’t always changing propaganda films to his will. It would seem that he let some of the German film industry produce films according to their society. It just so happens that that society had gone through some hard times and the Jewish people had been used as scapegoats for some time. It is possible that Goebbels didn’t have to use that much of his influence all the time after all. Goebbels might have had a lighter touch than we imagined only having a heavy hand in some particular film such as the ones aforementioned here among some others. Even with all his efforts it is not clear that propaganda was as effective as people may think. The following section briefly explores the effectiveness of earlier propaganda endeavors, compares it to the propaganda in the modern age and asks the question of if we are better off now or not.

Propaganda, does it work?

Is propaganda effective? It seems not, studies of the extent to which the American Why We Fight? films had been able to modify the attitudes of newly enlisted servicemen provided the first empirical data of the limited power of film propaganda (Reeves 7). The study shows that propaganda might be good to share information, but it had no effect on enlisted men’s motivation to serve as soldiers. So, what then is the point? Why did Germany spent all that money buying film companies, and why did Joseph Goebbels put so much effort into controlling each released film? It would seem that perhaps there wasn’t much known about the effectiveness of propaganda at the time. Goebbels and Hitler might have just assumed that it worked when in reality, their support was mostly due to the economic conditions Germany was facing at the time and the timing of the German economy’s recovery. The Nazis, unfortunately for the world, seems to have been at the right place at the right time. Maybe modern data collection and processing technology is needed to make propaganda work, but that already happens, perhaps it goes by different names such as targeted ads, customized sponsored content. Also, we are probably bombarded with it more often now, how many YouTube ads do you see per day? How many political Facebook posts do toy scroll through? A person in Germany might have seen propaganda in a film every so often, but we see them every day.

Conclusion

The Nazis certainly weren’t the first to think of using propaganda, nor was their use of propaganda particularly special at the time, and propaganda is by no means only used by the likes of the Nazis. What is certain is that it is still used today. We see it in new mediums such as Facebook posts, YouTube ads, self-promotion by influencers, and in all manner of political mediums such as TV ads, rallies, and plain old speeches. The only thing that has changed about propaganda is its name, propaganda has been a derogatory term for a long time, and nobody would want to be called a propagandist. Worse still is that it seems old-school propaganda isn’t particularly effective in changing people’s ideas and you still run the risk of being branded a propagandist. However, modern propaganda is a different animal. Back in the day, propaganda was a one-way street, nowadays, you participate in its creation, making it a two-way street. Propaganda listens to you, collects your clicks, it knows you and it is designed just for you.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

Schocken/Random House, ed. by Hannah Arendt;, 1936.

Boland, William. “Hitler’s Use of Film in Germany, Leading up to and During

World War II.” Inquiries Journal, 1 Mar. 2010, www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/206/hitlers-use-of-film-in-germany-leading-up-to-and-during-world-war-ii.

“Cinema and Filmmakers Under the Nazis | Filmportal.De.” Filmportal,

www.filmportal.de/en/topic/cinema-and-filmmakers-under-the-nazis. Accessed 23 July 2021.

Facing History And Ourselves. Holocaust and Human Behavior. Facing History &

Ourselves National Foundation, Incorporated, 2017, www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter-6/propaganda-movies.

Kracauer, Siegfried. The Mass Ornament. Duke University Press, 1975,

www.jstor.org/stable/487920.

Reeves, Nicholas. Power of Film Propaganda by Nicholas Reeves (2004–03-01).

Bloomsbury Academic, 1999.